Eight Contemporary Poets I Love and Two Dead Guys I

In anticipation of National Poetry Day this Friday, one of our favourite New Zealand poets, Hera Lindsay Bird, shares ten poets who have shaped the way she thinks about poetry.

One of the worst parts of having a postgraduate degree in poetry is having to tell people I have a postgraduate degree in poetry, because it’s always followed by the inevitable: "Oh." I’m asked to explain why poetry is important, which is a question I find difficult to answer, partly because I don’t know if poetry is important and partly because I don’t care. I always feel uncomfortable when people talk about poetry as being important in invisible italics, because they’re usually using ‘important’ as a synonym for “worthy,” or the even more terrifying “improving,” and as Frank O’Hara says:

How can you really care if [poetry] improves them. Improves them for what? For death? Why hurry them along? Too many poets act like a middle-aged mother trying to get her kids to eat too much cooked meat, and potatoes with drippings (tears). I don't give a damn whether they eat or not. Forced feeding leads to excessive thinness (effete). Nobody should experience anything they don't need to, if they don't need poetry bully for them. I like the movies too. And after all, only Whitman and Crane and Williams, of the American poets, are better than the movies.

I blame high school English for a lot of our common misconceptions about poetry, particularly for inventing the idea of a poem as a kind of linguistic code you have to crack in order to get at some deeper meaning, as if poetry’s primary goal was to illuminate some facet of human experience by deliberately trying to conceal it from the reader, which is about as fundamentally moronic as inventing a satellite navigation system that intentionally diverts cars into a lake, in the hope that the experience of being in the lake will allow drivers to better reach their intended destination. I don’t mean that poetry has no room for deceit, or detours, or any of the other stuff that makes life (and writing) fun. One of the poets on this list, Mark Leidner, says:

I tried to be as earnest as possible, which to me doesn’t preclude ambiguity, and maybe even is necessary for the most ambiguous ambiguities. It’s hard to answer this question because earnestness in one echelon of form can easily lead to irony in another. Like how if you really want to win a war, you might decide to be deceptive in a battle. You might even fake losing a battle in order to later enact a more stunning reversal. Is that strategy a corruption of your earnestness? Or the proof that your desire to win is in the highest earnest. Good opposites always touch each other and I think the point at which they do is where it starts.

My point is that poetry is not a trapdoor for the uninitiated to fall through. Poetry shouldn’t need disclaimers (guilty as charged) or any kind of instruction manual. When thinking about meaning and the “ambiguous ambiguities” of poetry, I often come back to this fragment of Wallace Steven’s A Rabbit as King of the Ghosts which goes “And to feel that the light is a rabbit-light/In which everything is meant for you/And nothing need be explained.”

I have a lot of energy for poetry. But I also know how difficult it can be to find good contemporary poetry, mostly because it either exists in limited edition chapbooks, or on the internet, and as everyone knows the internet is an evil vortex of uncensored emotional outpourings (see above.) I’m not the world’s greatest cheerleader for poetry, but I’ve compiled a list of ten poets who I love and who have shaped the way I think about poetry, and hopefully they’ll do their own cheering.

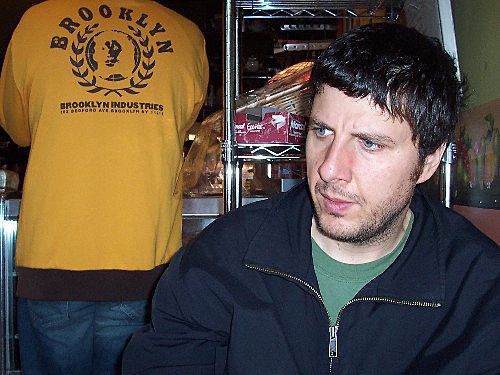

Mark Leidner

The order in which the poets appear in this list have no numerical significance because I feel like ranking is usually an unproductive exercise (with some notable exceptions), but I’m going to break my rule just once to say that Mark Leidner could be all ten of my top ten and then some.

It’s difficult to know which poem of his to choose, because they’re all so long, but to provide only an excerpt would be to reduce his work to a series of (admittedly dazzling) one liners.

It’s like trying to refight WWII entirely by karate chop.

It’s like kissing someone with lipstick made of crushed match heads.

It’s like eating dick off a paper plate

You have to cry blood like two wild nuns leaving your eyes and sliding down your cheeks in shiny red convertibles.

The cumulative effect of these of lines are so important to his poetry’s momentum. What I like about his poetry is the way it follows jokes past their logical conclusions and into uncharted territory, unearthing something astonishing. That takes a kind of grim determination. It’s like seeing a friend at an ATM and deciding to pretend to mug them as a practical joke, but instead of laughing when they turn around with their hands raised, forcibly taking their cash and spending it on a plane ticket to Nebraska where you work for the next fifty years as a corn farmer only to softly whisper "just kidding" to nobody on your deathbed.

Mark Leidner has this to say about joke telling in poetry: “Because the logic of jokes hinges on misdirection, maybe jokes are inherently insincere, and therefore counter to poetry. You get the audience thinking one thing, then flip them. But poetry, it seems to me, is language stripped of misdirection. If the thought flips, it is because the thought has flipped the thinker. Joke-tellers know where their punchlines are going to land. Joke-tellers know, poet’s don’t.” I can’t talk about Mark Leidner. He defeats me. The River is one of my favourite ever poems, but it’s also not very characteristic of work, so you can go here to read one of my other favourites, Blackouts.

The River

The woman told me the saddest thing I had ever heard. I told her I loved her because of what she had told me. Her expression soured. She warned me not to love her for her telling me that. She told me it was okay, and maybe even good, to love her – only not for that. I responded that I did not love her for that, exactly, and that she had misunderstood me. I admitted that why I loved her was related to what she had told me, yes, but only tangentially, and was that alright? She asked me to elaborate, so I told her that I loved her, not for the thing she had told me, but for the courage involved in telling someone something like it, something that sad, which seemed to me to be a great deal of courage – and I told her I also loved her, though far less than for the courage part, although plenty still, for the way in which she told it to me, which I explained had been, in all seriousness, eloquent and mesmerizing. She had a small build and at that point she laughed like a flower, wilting and blooming. Her nose was in the center. I decided to show her the river. I picked her up in my hands and carried her, crisscrossing back and down through the steep and elaborate cragwork of the slope of the riverbank. When my feet were finally in the water I looked at her and said, the river is deep, and fast, and it drowns many people, but I still love it. I still love the river, I told her. But I do not love it because it is deep, and fast, and drowns many people. I love it because it runs behind my house, and I have lived above it forever.

Lauren Ireland

I love Lauren Ireland. I love her with Japanese masking tape & exotic beers. Lauren Ireland is not the new Frank O’Hara of poetry because nobody is the new anyone of anything, but if I were her, I would watch out for dune-buggies. Her work shares some of the same startling emotional openness and reckless humour that I love in his work. I’m a sucker for Lauren Ireland, partly because I love all things wizard, but I also want to mention recklessness again, so I just did. Again, as with Mark Leidner, I don’t want to deconstruct everything I like about her, because poetry’s more than the sum of its components, but how could you not fall for someone who is able to conclude a melancholy personal poem with the lines “Snow, who cares. /I have seen a shark’s vagina.”

LEIGH STEIN’S BIRTHDAY

for Leigh Stein

Leigh I love you. I love you with

Japanese masking tape & exotic beers.

I am going to drink more beer than

anyone else even boys I am going to

make the largest wizard staff in the world.

I was also going to summon something

wonderful but you are already here.

Matthew Zapruder

I’m writing these author paragraphs fast, one after another, and my head is beginning to feel like a spaceship from the seventies. I want to be careful with these poets, but not overly careful. When creating this list, I thought it was more important that the list was an honest representation of the poetry I really loved as opposed to a list that reflected stylistic diversity, mainly due to who cares, but it does mean that many of the featured poets have similar influences and are up to the same linguistic tricks, so it can be difficult to isolate exactly what it is that makes them stand out. That every poet on this list can use language in surprising and innovative ways, and has something important at stake in their work is a given. And as Frank O’Hara says “As for measure and other technical apparatus, that's just common sense: if you're going to buy a pair of pants you want them to be tight enough so everyone will want to go to bed with you. There's nothing metaphysical about it.”

But I think that what sets Matthew Zapruder apart for me is his engagement with the world. As a phrase, “engagement with the world” is terminally vague, and could mean a myriad of things but I think what I’m trying to say is said better by Matthew Zapruder in a fragment from one of my favourite of his poems, Pocket.

Today the unemployment rate

is 9.4%. I have no idea what that means. I tried

to think about it harder for a while. Then

I tried standing in an actual stance of mystery

and not knowing towards the world.

Which is my job. As is staring at the back yard

and for one second believing I am actually

rising away from myself. Which is maybe

what I have in common right now with you.

And now I am placing my hand on this

very dusty table. And brushing away

the dust. And now I am looking away

and thinking for the last time about my pocket.

But this time I am thinking about its darkness.

I love the transparency of that. “Standing in a stance of mystery and not knowing towards the world,” is the task of all good poetry. And MZ reminds me how standing in that stance of mystery is a constant effort, but it’s an effort that’s always rewarded.

In Wichita Kansas my friends ordered square burgers

with mysterious holes leaking a delicious substance

that would fuel us in all sorts of necessary beautiful ways

for our long journey eastward versus the night.

I was outside touching my hand to the rough

surface of the original White Castle. I was thinking

major feelings such as longing for purpose

plunge down one like the knowledge one

has been drinking water for one's whole life

and never actually seen a well, and minor ones

we never name are always across the surface

of every face every three seconds or so rippling

and producing in turn other feelings. Oh regarder,

if I call this one green bee mating with a dragonfly

in pain it will already be too late for both of us.

I am here with that one gone, and now inside this one

I am right now naming feeling of having named

something already gone, and you just about to know

I saw gentle insects crawling in a line from a crack

in the corner of the base of the original White Castle

towards only they know what point in the darkness.

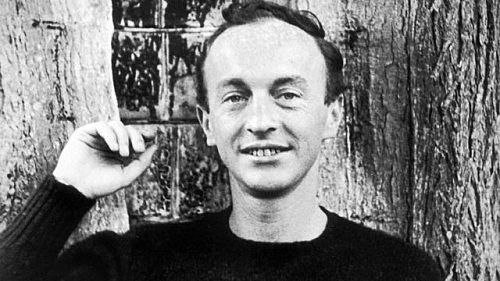

Frank O'Hara

Frank O’Hara has earned the rare distinction of being one of the only dead people on this list (the other being James Wright). My favourite ever story about Frank O’Hara is the time he was doing a poetry reading and a drunken Jack Kerouac started heckling him, shouting “You’re ruining American poetry O’Hara,” to which O’Hara replied “That’s more than you ever did for it, Kerouac.” I could stop there, but I won’t. I don’t have much to say about Frank O’Hara because anything I could say would be immediately eclipsed by his own words, because O’Hara is the most alive dead ghost I know, but I will just say that reading Frank O’Hara changed the way I thought about poetry. This poem is not my favourite O’Hara poem, but it’s the first one I fell in love with, and I think it’s a good introduction to his work. Frank O’Hara is the world’s lightest heavyweight. I love him for his energy and his daring and his quick emotional shifts that can flip you so effortlessly.

Having a Coke with You

is even more fun than going to San Sebastian, Irún, Hendaye, Biarritz, Bayonne

or being sick to my stomach on the Travesera de Gracia in Barcelona

partly because in your orange shirt you look like a better happier St. Sebastian

partly because of my love for you, partly because of your love for yoghurt

partly because of the fluorescent orange tulips around the birches

partly because of the secrecy our smiles take on before people and statuary

it is hard to believe when I’m with you that there can be anything as still

as solemn as unpleasantly definitive as statuary when right in front of it

in the warm New York 4 o’clock light we are drifting back and forth

between each other like a tree breathing through its spectacles

and the portrait show seems to have no faces in it at all, just paint

you suddenly wonder why in the world anyone ever did them

I look

at you and I would rather look at you than all the portraits in the world

except possibly for the Polish Rider occasionally and anyway it’s in the Frick

which thank heavens you haven’t gone to yet so we can go together the first time

and the fact that you move so beautifully more or less takes care of Futurism

just as at home I never think of the Nude Descending a Staircase or

at a rehearsal a single drawing of Leonardo or Michelangelo that used to wow me

and what good does all the research of the Impressionists do them

when they never got the right person to stand near the tree when the sun sank

or for that matter Marino Marini when he didn’t pick the rider as carefully

as the horse

it seems they were all cheated of some marvelous experience

which is not going to go wasted on me which is why I am telling you about it

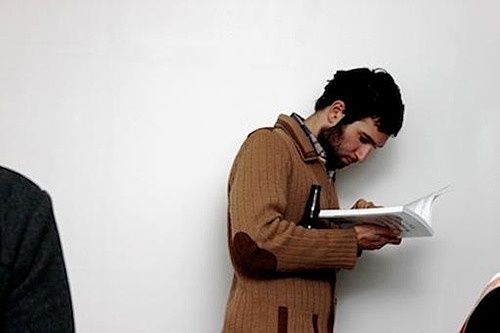

Lee Posna

Lee Posna is the poet I’m most wary of writing about. I love what little I’ve read of his poetry, but I feel ill-equipped to talk about it in any considered way because his work exists so far outside of my usual frame of reference. I can go as far as tentatively linking him to Anne Carson and Wallace Stevens, and then I have to slowly back away into the forest with my hands raised.

LP is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and doesn’t have a lot of work available on the internet, but this poem was recently featured in the sixth issue of Hue & Cry. I have read this poem many times, and each time I do, I am amazed and edified by it.

Ryan I Would Return to Oregon

by stopping. In the circle of a wind

I’d stop, and I’d go back to Oregon.

By following the pullulating firs

up northern California, barefoot;

or from the east by bike, via the Snake

of Idaho, I know a woman there

in Grangeville, let me camp in her backyard

under the wrinkle of a wild wind.

I would return to see you, Ryan, you are

the Douglas-fir—who else? Across the sea,

across the ever-manifest Pacific.

That beatific, other blue for me

inhabits fate because it came to be,

as things delayed and good seem destiny

and thereby are. I could drop a full stop

like a bronze anchor in the offing of

that end that was the start of a fucked-up

terrestrial, howling fate, but it would float

like any night. I would return to see

sky-firs plunging down the soaked Cascades,

and Silver Falls. When every living thing

was green—the rainy winter green, as green

as a child’s spring, the loud light, lifelike pines

the lesser permutations of desire,

that great green Golgotha, more ghost, less haunting;

and stars in rivers vernalizing space

and the green circle of a homeless wind

I knew in marijuana's shaggy sight—

do you recall the circle, Ryan?—

on hikes through Forest Park and Tryon Creek

we rendered moments bulbous, youth-dark, long,

inviolable-dark, as dark as deep sleep,

the country of my family . . . thought I’d left.

And like a dream in which I was awake,

the bare surreal with felt fate overgrown,

I knew you knew essentially my life,

and that too singular to leave behind!

I would return to take an empty look

as though this were some other person’s life,

and sink past all colour to the bottom of my dream—

surely it has a bottom, for we know

it has an end. I want to see about

the sparks of spirit I scattered there

freewheeling through an ancient forest down

the narrow road between one loss and its long thought

condemned to suffer hidden generation;

though no one knows exactly when or where

he goes astray in the endless finitudes

of moss and bark: a hidden point becomes

the heart if not the bottom of his life.

*

Tune in for Part II, in which Hera shares four more contemporary poets, one more dead guy, and two incredible bonus rounds.