Bloomin' Schemies: Dieneke Jansen's 'Dwelling on the Stoep'

Janet McAllister on an exhibition about social housing that refuses to dwell on dwelling deprivation.

Janet McAllister on an exhibition about social housing that refuses to dwell on dwelling deprivation.

The Scots – as we were recently reminded, thanks to clueless numpty Donald Trump – treat slanging matches as national sport. Wandering around the social housing blocks depicted in Dwelling on the Stoep – Dieneke Jansen’s current exhibition, which achieves the mid-2016 holy grail double-whammy of relevance to both Brexit and the New Zealand housing crisis – I was reminded of (the) one Scots insult not flung at Trump: “schemy bastard”. Also funny, but potentially far more offensive than, say, “gobshite”, “schemy” doesn’t mean scheming, cunning, conniving or wily; it means “living in the schemes”, the social housing projects. To be schemy is to be deprived and therefore to be despised.

However, Jansen’s exhibition does not document such interpersonal contempt (governmental contempt is another matter), nor does it dwell on dwelling deprivation. Instead, her works counteract the schemy stereotype, and depict courtesy, warm social interaction and pleasure in supposedly “failing” housing developments. We hear the voices of housing block residents: Jakarta pre-schoolers eat together in communal space; their older brothers talk about their skateboarding club; their mums talk about how they’ve had to learn to get along with neighbours from different parts of the country (why, hello there, intra-national multiculturalism). In my favourite video works of the exhibition, Bijlmer Bloemen, Jansen hands out huge bunches of flowers to housing residents in Amsterdam, because any good guests in Holland offer bouquets to their hosts. Some of her “hosts”, in response to her questions, say how happy they are to live where they do. They say that outsiders think Bijlmermeer is crime-ridden “but that has not been my experience”.

Jansen does not offer such enthusiasm as the whole story – she is interested in interrogating and complicating, not in offering propaganda – but the positivity is real, and it is therefore a surprise. Where are the monochrome, knife-wielding, schemy bastards whom Roddy Doyle has led us to expect? Where is the tinderbox multicultural gun-stealing frustration shown in the cités of La Haine? Not here; Jansen’s work shows other tower-block possibilities, and – given that more than 30,000 New Zealanders are currently living in severe housing deprivation – these possibilities are worth exploring.

Stoep shows buildings in Europe, Asia and Oceania – more specifically, in Holland, Indonesia and New Zealand: the coloniser, the once-colonised and the white-settler colonial. The depictions include Jansen’s previous national home and her current one (she immigrated to New Zealand from Holland as an infant); outer suburbs and central city blocks; buildings constructed in the 1950s, the 1960s and the 2000s. Multiple rich comparisons are therefore available – between national, local or architectural contexts – which shift the concept of “home” and allow for the exhibition’s omnibus current-affairs commentaries. For example, does a social housing project “fail” because of its layout or because of where it’s located, or is it all the fault of the schemy bastards? (The Jakarta and Auckland works – showing buildings of different layouts and sub/urban locations – suggest government indifference is a more likely problem, manifested in a lack of maintenance and a surfeit of evictions.)

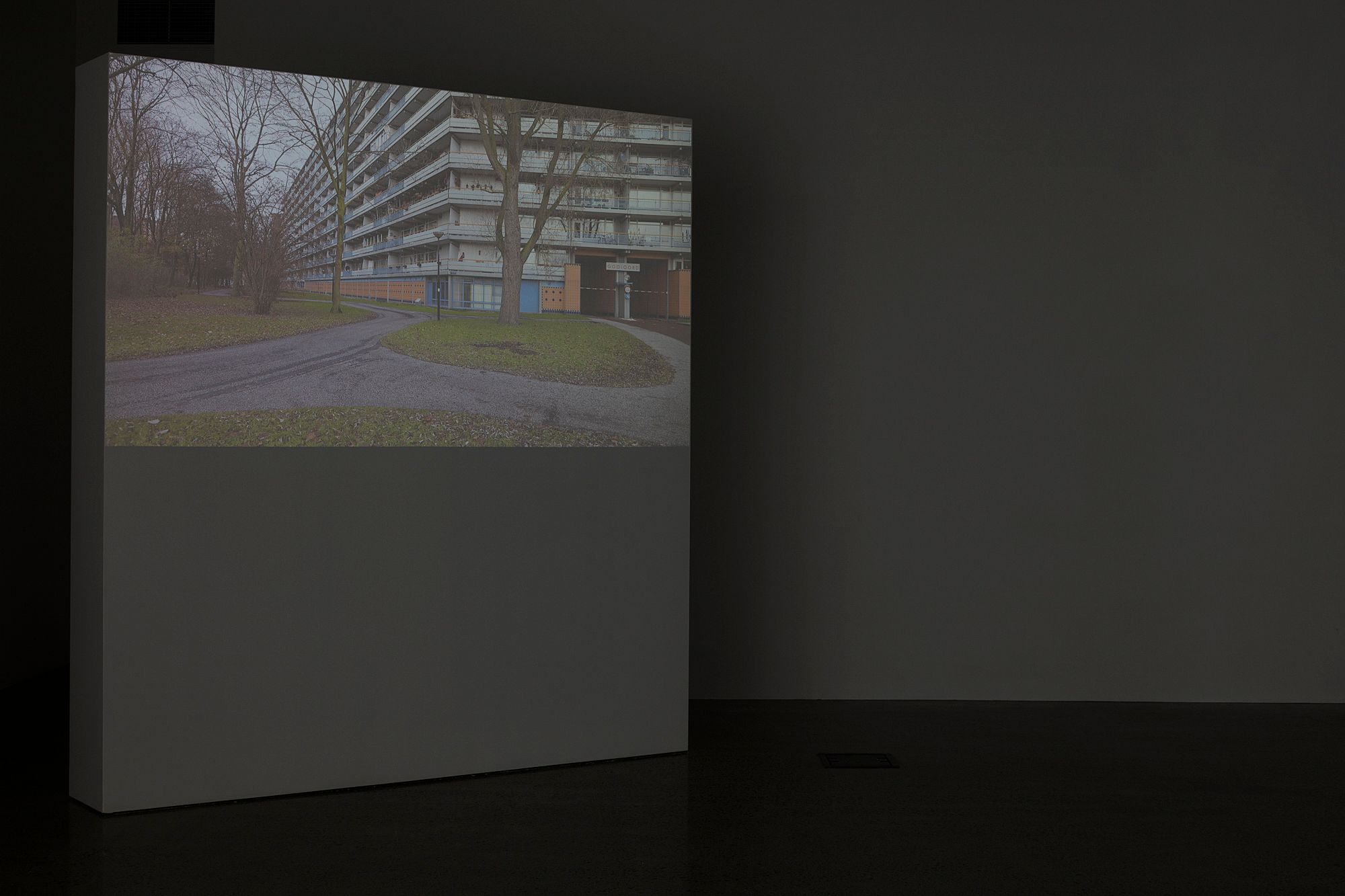

Or are announcements of failure premature? We come back to the residents’ enjoyment of their homes, peeling paint notwithstanding. The exhibition is laid out at AUT’s ST PAUL St Gallery to enhance the reveal, the surprise, of their delight. At first, you see images designed to look desolate: photographs of places for people that are empty of people. In the window box visible from the street are two stunning photo banners showing slices of the 1958 Housing New Zealand apartment blocks situated only a few hundred metres from the gallery, at 139 Greys Avenue. The rhythm of the Greys Ave modernist façade is implacably regular; in miniature, it’s a soothing pattern, even if its fitness for human habitation is debatable. (Too monotonous? Too big? Do we yearn for difference, a smaller grain and irregular punctuation?)

The next thing you notice are the small individualities, traces of the people missing in the photograph – washing, potted plants, a bamboo screen – lending humanity to the cold if beautiful exterior. The final feature I noticed was the wiring falling down over the front doors, over the stoops. You can imagine HNZ shrugging, “Why maintain it? It’s just for schemy bastards.” (A thick supplement accompanying the exhibition contains a press release asserting that residents were told it could take ten days for a blood-spattered elevator to be cleaned, as well as an excellent AUT student article describing how the HNZ office at Greys Ave – there to provide security for residents – closed down without notification for a month because it was considered too dangerous for staff. How Alanis Morrisette! Perhaps they had a knife when all they needed was ten thousand spoons?)

Jansen, an AUT senior lecturer, has made art about housing for several years now. She produced an effigy of Michael Joseph Savage so he could witness the dismantling of his state house legacy in Glen Innes. In 2013, she won the National Contemporary Art Award with a composite photograph of a former RNZAF airfield in Hobsonville “sold to the state then redeveloped under the Gateway Housing Scheme in 2008 before being axed in 2012”. It looks like Greys Ave may go the way of Glen Innes and, more recently, the uniquely curved 44 Symonds Street: cleaned out, boarded up and sold, with no plans to re-house the former residents appropriately. In this sense, the Stoep Greys Ave work is a continuation of Jansen’s documentation of (potential) social housing destruction. However, one can also interpret the Dutch and Indonesian-based works inside the gallery as indicators of alternative futures, in which high-density housing in New Zealand makes sense and shelters happy people.

Perhaps. The Indonesian works in Gallery One aren’t immediately propitious. The slow, hard-going interviews about politics and horticulture hint at trouble. (They’re also reasonably opaque, but then, broadcasting the idea that the visitor can never really know the full story is always useful.) However, when you turn the corner, the literal and metaphorical centre of the gallery is revealed: a dozen motley screens showing video loops of Jakarta’s Marunda housing residents describing their lives. Childhood sweethearts now married and expecting (“I hope she has a pointed nose like yours, miss!” says the husband to his wife), a man seeking a friend he thinks is in New Zealand, a woman who teaches adults to read. Nicely set on life-size photographs of the development’s cracked tiles, the interviewees’ hope and life-satisfaction are palpable.

In Gallery Two, the first thing you see, again, is buildings without people – this time, on a large projection, sculptural but slightly sad. And, again, when you turn around, you see people. Four screens show Jansen offering flowers outside four buildings and finding out how pleased the residents are to live near a market and a health centre. (As with the Jakarta works, the written translations mean viewers have the option of following more than one video at once; this bonus saturation is recommended for short attention spans.) Some bouquet recipients are originally from Africa. Jansen’s political gesture is to acknowledge, through the flowers, that immigrants to her birthplace are now her hosts, even though she still has Netherlands citizenship; that in some ways the development, the suburb and, yes, the country are now theirs more than hers. There will be many Europeans – many Leave voters, for example – for whom that idea is anathema. And the Netherlands is not without its own xenophobic politicians.

The act of giving flowers is a gesture of solidarity between transnationals and also an act of self-validation; by extrapolation, Jansen is now a host in New Zealand. Questions: when is someone allowed to feel they belong? Does it change depending on that person’s ethnicity? On their bank account? Do they have to “contribute” to belong? Who gets to decide what constitutes a valid contribution? (Add the refugee debate to the list of current issues touched on by Stoep.)

In one of the Bijlmer Bloemen videos, two nice little stories unfold at the same time. A man is already outside the door when Jansen arrives. She gives him flowers, but he remains there. He’s waiting for a taxi; the taxi is Godot; he doesn’t move. Small talk dwindles. Jansen is distracted, trying to catch the eye of other passers-by – a project perhaps made more difficult by the presence of the man beside her. It’s deliciously awkward. What happens when your recipients don’t fit your schemas, when they don’t do what you expect? What’s the plan when you have little to talk about, when there’s perhaps cultural as well as social awkwardness, but you’re sharing space?

Then the would-be taxi passenger engages another of Jansen’s flower-recipients, a polite young man, into a debate about whether he should cancel the taxi or just keep waiting. We’ve already seen the young man wedge a door open upstairs; maybe he’d forgotten his key. And while the taxi angst is developing downstairs, we see a man with a bicycle negotiate the wedged-open door on the floor above. He goes through the door, and then carefully rearranges the wedge so the door remains open behind him. He has done this for a fellow resident; we know who, but he doesn’t.

That, more than anything anybody says to Jansen, convinces me that the building is happy and the people feel secure. Anonymously leaving the door open – that is a kind considerate gesture. People who are fearful don’t do such things. Let us call it a metaphor for immaculate immigration, for contented multiculturalism, and a sign of successful social housing. Let us all become Schemy Good Samaritans.

Janet has written elsewhere on Auckland’s housing crisis and the concept of home.

Dwelling on the Stoep

ST PAUL St Gallery, AUT

10 June to 16 July 2016

Free admission