Displacing, Detaching: Good and Bad Refugees in Fortress NZ

Melissa Laing on the ongoing refugee crisis

There are certain moments in time when the world’s media pays sustained attention to the mass displacement of people, and because they do, we do. The cause of the displacement might be a natural disaster, an earthquake or a famine – currently, it's a civil war complicated by religious and sectarian divisions, food insecurity and the aftershocks of years of international intervention through the region.

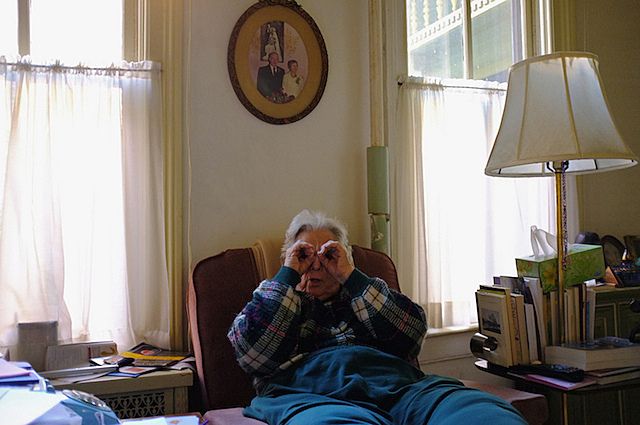

The stories in the news either show us families overcoming adversity or being torn apart by the dangerous journey, and we respond with an empathetic connection. Suddenly (in minutes now, as Aylan Kurdi’s little frame was replicated over and forever on social media), we worry for and about the people that make up the mass displacement it stops being some abstract, geographically distant matter and becomes human.

Maybe we donate money, sign a petition, write an article, make a semi-sincere offer to house someone, before we go on with our lives and let this most recent instance slip into the back of our minds, passing from outrage to history as it join a long list of population displacements. Maybe we actively do something more. We volunteer for our local Refugee Council or Red Cross branch, campaign for change on a sustained basis, take a job with a NGO.

Then again, maybe we reject that moment of empathy, blaming the people fleeing for the immediate consequences of their flight, to both us and them. We call for greater protections, less porous borders and more punitive treatment of those who slip through, driven by our worry that if we let refugees come here they will push us past our capacity to support the ethical treatment of our fellow citizens, a capacity we already fear (or insist) we've exhausted.

More often, we enact the two impulses simultaneously. Somehow, we're able to partition off the empathetic moment we have with the individual human from our subconscious rejection of the entire category of 'refugees'. This kind of cognitive dissonance is driven by the way the refugee, in the abstract, interrupts our comfortable assurance that citizenship will link us to territory, that we always have somewhere to go home to. The existence of masses of people disconnected from these support structures is a constant reminder that what we take for granted – our citizenship, our physical and psychological security, state protection of our rights, our income, shelter, food, home - can disappear from under us due to factors we have no control over.

The potential of this disconnection drives our often visceral rejection of the legitimacy, moral standing and humanity of refugees. Our problem isn’t that it's difficult to imagine ourselves as them - it's that it's easy. To armour ourselves against this lurking fear we assign a moral blameworthiness in the situation we’d never want to ascribe to our personal lives. There's no doubt that things are hard, but refugees must be at fault - maybe they've made bad decisions, or are trying to take advantage of our better nature. Politicians in Australia, the UK, Hungary, and elsewhere, play on this anxiety and insecurity garnering support by pursuing a fortified populism.

It’s not a surprise that the appeal works, because our legal being in the world and the rights that flow from it are built around our belonging to a sovereign nation-state. Even when we are away from it, our government affirms our identity through its mutual recognition of the legal existence of other nations. Through participation in treaties, conventions and international organisations, our legal personhood is ensured wherever we go.

Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben, in his collection of essays Means without End, argued that:

“If the refugee represents such a disquieting element in the order of the nation-state, this is so primarily because, by breaking the identity between the human and the citizen and that between nativity and nationality, it brings the originary fiction of sovereignty to crisis.”

This originary fictions of the nation state - that all humans are citizens, citizenship is an automatic right of birth, and the nation is formed from and legitimated by the total mass of citizens within its physical territory - become even more brittle yet tightly-held held in postcolonial countries like New Zealand. It's easy to lose sight of the fact that New Zealand citizenship didn't exist until 1949. Pākehā held on to the idea of natal Mother Britain well into living memory, while our originary act of nationhood is one of colonisers treating with tangata whenua, not the coalescence of nativity and nationality. Whenever we speak against welcoming humans displaced from their homelands, using arguments about the preservation of nation, economy and culture, we wield a two edged sword. A sword which cuts open one construction of sovereignty to reveal the historical demands of another.

As a nation of people who've built assertions and assumptions of nativity on top of waves of migration, it is notable that governance of 'New Zealand' has long involved attempting to control the nature, origin and purpose of the waves that came next. From our first parliamentary debates onwards, the function of immigration has consistently been described as to contribute to New Zealand’s growth (physically and economically) through the positive migration of a centrally defined ‘right kind of person’.

To this end, Acts of Parliament have been passed which legislate to actively solicit the movement of the ‘right’ people to come New Zealand to work and reside here, and to militate against the movement of people who do not meet these criteria. Somewhere in between, we've taken advantage of flows of temporary labour from outside our borders too, secure in our right to send people away when they aren't needed, responding aggressively when they don't.

At the heart of our successive immigration acts is the state monopoly of the right to choose who migrates to New Zealand and under what terms. And while we may have moved away from the explicit racism enshrined in our earlier acts, the principle at the heart of our contemporary legislation is the same: to manage, or control, the flow of people according to the interests of New Zealand as determined by elected members of parliament, the public servants that act as their delegates, and the businesses invited to provide input.

To quote the Department of Labour-produced Briefing for Incoming Ministers from 2008:

“Immigration policy complements the domestic supply of labour by providing employers with the opportunity to recruit the skilled and talented people needed to sustain and grow globally competitive businesses. … Our border controls are aimed at keeping out those we do not want and increasing use of offshore screening prior to travel allows us to push the border offshore.”

The way New Zealand has long dealt with refugees reflects both this desire for and ability to control movement. We resettle refugees who the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has affirmed are refugees. In the past we acted intermittently, erratic gestures of generosity reacting to individual crises. Since 1987 we’ve operated within our formal agreement with the UNHCR, which is currently to resettle a maximum of 750 people a year. Murdoch Stephens eloquently addressed the inadequacy of this quota earlier this year in Overland.

Like many countries, New Zealand is uncomfortable with the loss of control onshore applications represent, pushing our borders out beyond our shores through Advance Passenger Processing to keep their numbers low. We only formally implemented a process to assess the veracity of an onshore refugee status application in our immigration legislation until 1999. The same year, we first introduced provisions to automatically detain large groups of asylum seekers. In fact, in the last 20 years MPs have twice argued for and passed laws to incarcerate large groups of asylum seekers. Among the justifications used in both 1999 and 2013 was the asserted yet unrealised imminent arrival of a boat filled with people on our shores. The spectre of a boat, and the rupture of sovereignty it represents, is enough to spook us.

Last week, our government announced that it would resettle 600 additional UNHCR refugees of Syrian nationality in the response to public pressure, 200 people a year on top of our annual quota. With just under 60 million people forced to flee their homes worldwide, 38 million still inside their own countries, the rest either across a border at the nearest safe point or actively moving further away, our latest gesture of generosity seems small. True, we also pledged an additional $4.5 million in financial aid to the UNHCR on top of our existing contribution of $6 million. But both decisions came late, made begrudgingly after all the impediments had been listed.

Those impediments were all economic arguments for a world which increasingly uses the language of economics to measure the value of everything, including human existence. In the context of the current crisis, those arguments seem one-dimensional, reinforcing a comfortable status quo and missing the opportunity to cohesively reshape how we consider seeking and granting refuge. We need to stop seeking a clean moral divide among those seeking refuge – dependent victim, economic opportunist – to justify the giving or withholding aid and move toward a nuanced recognition of the nexus of responsibility and opportunity that is created each time we give people refuge here. A relationship that is more complex than an economic cost/benefit analysis can ever reflect.

The answers to the questions presented by the multiple humanitarian crises that cause and follow refugees are complicated, conditional and constantly changing. In trying to find them we get caught in a chicken and egg discussion - do the refugees cause the crisis (as a sudden demographic flow of desperate humanity), or are they caused by the crisis?

In seeking answers, we assert that if we solved the push factor the problem would go away, while also arguing that if we make it really horrible or impossible to come the problem will go away (from us at least). We send military in to fight wars which displace people as we close our boundaries to prevent people from moving in. We celebrate our own historic flows of people from one place to another and recognise our earlier moral failures in times of war and need, but by and large we demonstrate we've learnt nothing from them outside of a set of heel-dragging and reluctant measures.

Global instability might be a wicked problem, but it's one the New Zealand government (and others) exacerbate with inconsistent responses. We argue for the moral legitimacy of military intervention in the Middle East while denying responsibility for the outcomes when they worsen rather than improve the conditions for people living there (at Pundit, Andrew Geddis is good on this). In the meantime, we offer parsimonious numbers of resettlement places and delay extraordinary action in the hope that the people in UNHCR camps will eventually return to their homelands.

Then we wonder why, faced with the prospect between 7 and 17 years in a refugee camp with limited facilities, minimal education opportunities and total dependence on charity, people choose to take matters into their own hands. We blame the people caught in these wicked problems for not sitting there waiting quietly for the world to fail to solve it. We blame them for taking risks when we’ve closed the other options.

These moments in time when human displacement has the potential to fire up our best and worst qualities are becoming more frequent, the intervals between them shorter. We are only seeing the tip of the problem now - in the face of resource constraints, climate change, and the increased militarisation of borders, it's likely fortunate countries like ours are about to see a lot more. We must find adequate and humane solutions both for the push factors that displace people, but also for the care of those displaced. If we are to do this, we need to overcome the pathological fear that the refugee strikes in the heart of the nation-state – a fear that was constructed outside of us, but that we've well and truly internalised.

We need to overcome our inclination to quarantine refugees in camps, creating illusory and irrational barriers against chaos. More than anything, we need to recognise and accept flux - that our desire to control who comes to New Zealand and our narrow frameworks for who is 'right' and therefore 'belongs' will be strained and changed, hopefully for the better, by these present and future flows of people, much as they have been in the past.