Your Brain Can Be a Dick: Disabled Writers and Ableism in Aotearoa

Elizabeth Heritage argues for greater accessibility in the New Zealand literary community

Elizabeth Heritage argues for greater accessibility in the literary community.

Across Aotearoa right now there are disabled writers creating everything from spoken-word poetry to films to bestselling paranormal romance. We can sometimes be tricky to spot in the wild – especially if we have one of the less visible forms of disability – but we are here. At the moment, disabled writers are creating art despite living in a society that ignores, misunderstands and sidelines us. Imagine how much more we would have to offer the readers of Aotearoa if accessibility were the norm.

Almost one quarter of New Zealanders identify as disabled. This includes people with physical, sensory and learning disabilities, and some people with chronic physical and mental illnesses. You might know more disabled people than you think: some disabilities are invisible and some disabled people choose not to talk about it much. Most people assume that being disabled must be bad – and it sure can be, but probably not for the reason you think. It is not so much our various conditions that are holding us back: rather, it is society’s ableism – its default prioritisation of non-disabled people – that is the true disability. Using a wheelchair would be no trouble if everywhere had good ramps. Or, as non-fiction writer and disability activist Robyn Hunt puts it, “We’re not the problem, it’s society’s response to us that is the problem.”

So often, accommodating disabled people is put in the ‘too hard’ basket (if considered at all), even when the effort required is slight. This is true in te ao pukapuka – the literary world – just as it is in society at large. For instance, the New Zealand Society of Authors’ Wellington branch used to hold its meetings upstairs at the Thistle Inn – a building with steps up to the front doors and no internal lift. I used to be on the committee and when I pointed this situation out, the response was that no disabled people had tried to attend so it actually wasn’t a problem – circular logic, to say the least. I don’t say this to single out the NZSA in particular – in fact I’m pleased to learn they’ve since moved their meetings to Vic Books Pipitea, which has ramps. But I share this as an example of the ways in which disabled writers are regularly excluded without anyone really noticing.

People with disabilities are often viewed with a combination of pity and distaste. Poet, playwright and novelist Helen Vivienne Fletcher says, “Sometimes even the doctors avoid you because your diagnoses make them feel powerless.” The way disabled writers are regarded is closely related to the representation of disabled people in literature itself. If they are there at all, disabled people are often portrayed in a disempowering way: they are hardly ever a main character, and usually are either cured or die at the end. This betrays the ableist assumption that disabled lives are less worth living. As Hunt says, “Disability is an integral part of the human experience, but it is neither valued nor celebrated.”

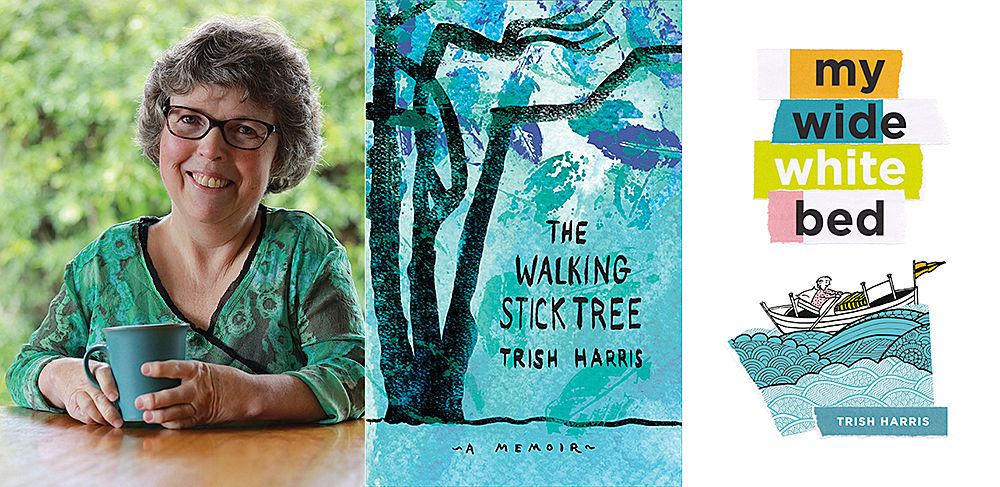

Kiwi writers with disabilities are responding to this in a variety of ways: some, like Trish Harris, are writing memoirs and poetry that directly centre their own experiences. Others, writing fiction, are creating disabled characters. In a world so starved for representation of disability, they wrestle with the need to be all things to all disabled readers. Fletcher wants to write a fantasy novel about a character who has an autoimmune disorder due to being a changeling, but says, “It feels scary to write because of the need to get it right.” She is forging ahead, though, and has a new novella, We All Fall, coming out later in 2019 with two disabled main characters.

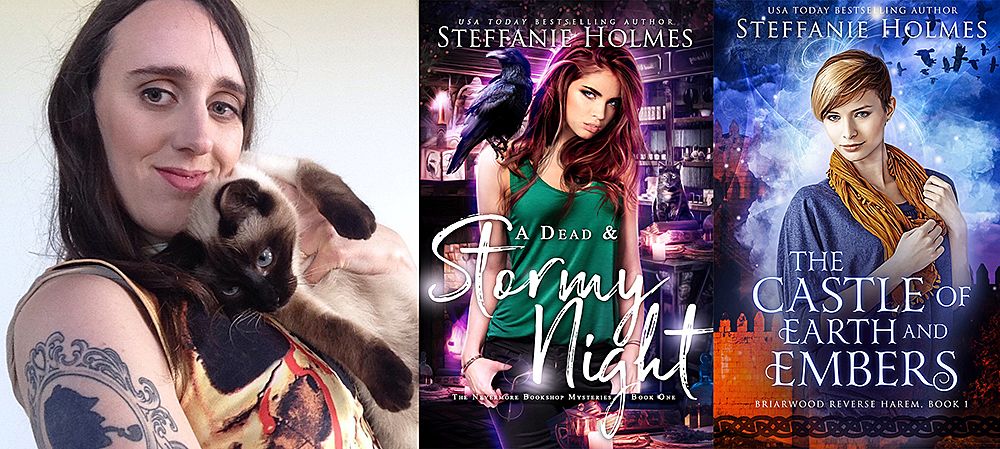

Disabled writers also face the risk of losing sales by centring disabled experiences. Steff Green, who writes a range of highly successful commercial fiction, says that, to put it baldly, “books with disabled characters don’t sell as well.” However, she is persevering. She worries, “If I’m not writing disability stories, am I reinforcing stereotypes?”

Green is legally blind; her disability is perceptible in person but not online. Although she identifies as disabled, she does not include this information in her main author bio. “The people who pay my bills don’t care, so I get to be invisible, which is kind of nice.” Invisibility can be a relief when your body is often treated as public property, prey to unwanted comments, touching (or even grabbing), and misdirected ‘help’. Fletcher often gets mistaken for a blind person, because she has an assistance dog – whereas Green, who doesn’t, is often mistaken for being drunk, and judged accordingly.

Green can’t drive and has had a lot of unpleasant experiences on public transport: “After a while you think everyone’s going to react badly.” Avoiding commuting was a key factor in choosing self-employment and working from home. Many disabled people become self-employed after facing (often illegal) barriers and discrimination in their job searches. Others combine freelance and part-time work. It becomes necessary to create your own employment structure when faced with ableism in the world of work on the one hand, and the restrictions of your own condition on the other.

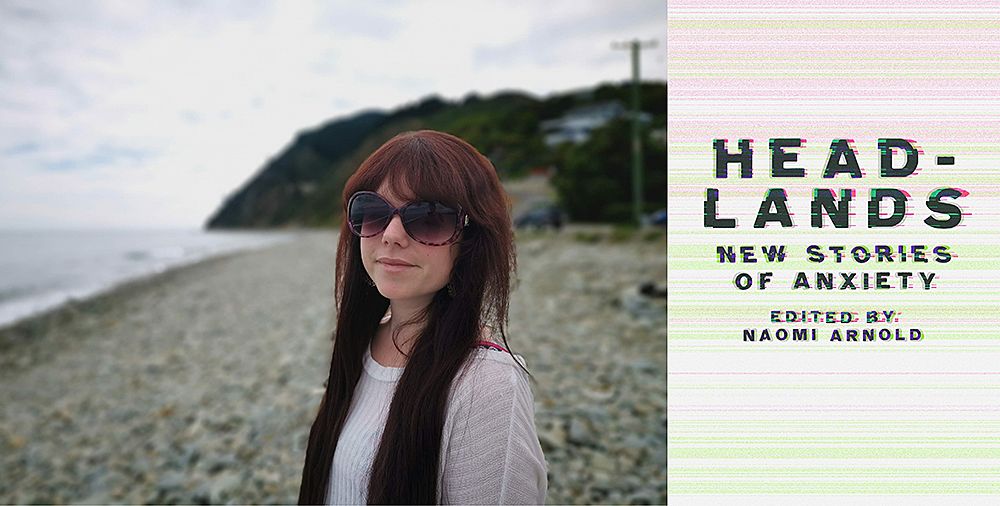

Sarah Lin Wilson is a writer and journalist who developed a chronic illness as an adult. “My career is nothing like what I envisaged when I was well. Now my life is dictated by WINZ.” As Hunt says, poverty and disability go hand in hand. For Wilson, one of the most difficult things about coming to terms with the realities of being disabled has been to unravel the connection between her productivity as a worker and the worth she feels she has as a person. She has to remind herself that there many different kinds of labour, much of which is unpaid, and that all humans have inherent worth regardless of the amount of labour they perform or how much money it generates. That can be easy to forget when you feel yourself slipping way behind your peers and failing to hit the career milestones you ‘ought’ to be meeting. But the reality of the body cannot be denied. Wilson says, “At one point I was so tired I thought I might stop breathing and die.”

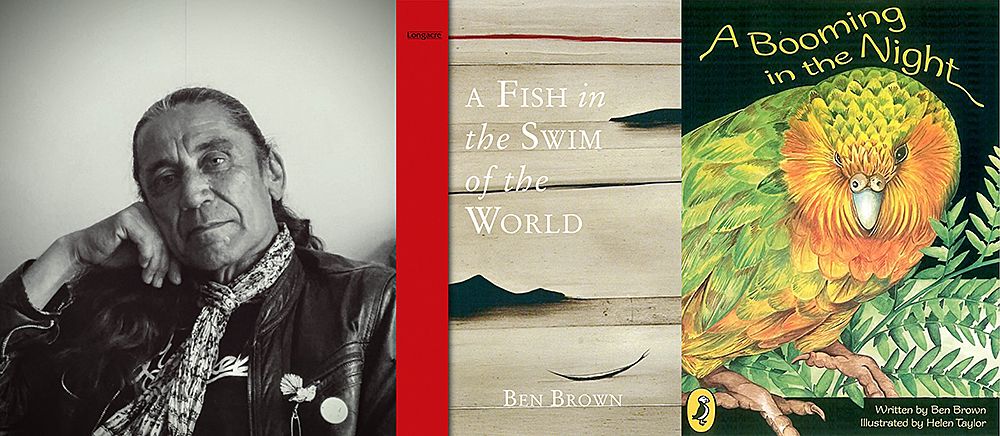

Poet and children’s author Ben Brown (Ngāti Mahuta, Ngāti Korokī, Ngāti Paoa) is also grieving the loss of physical capabilities he assumed he would always have. In 1983, aged 21, he had a motorcycle accident that nearly killed him, and left him without the use of one arm and in chronic pain. “I was in a deep, dark place – there’s still a big part of me that hasn’t dealt with it. Addiction became a big part of my life. I’m clean now but I’ve been close to the end two or three times.” He turned to writing, and ran a successful self-publishing business with his now-ex wife, illustrator Helen Taylor, for many years.

Stella Carruthers is a poet and novelist living with fibromyalgia and bipolar disorder. After lots of trial and error, she has managed to create an employment situation that works for her, working 30 hours a week as a library assistant as well as carving out time to write and read every day. “You need to recognise your own limits.”

Of course disabled Kiwi writers, like writers everywhere, also choose writing as a career in order to express something inside them that needs to be exorcised onto the page. Wilson says being a writer is her identity; Carruthers calls it her religion, and uses writing as a way to manage her chronic pain. “You have to get it out otherwise it festers – I always feel much better afterwards.” Carruthers is currently working on a novel about a woman who travels the world. “It’s a way to live lives I can’t live.”

Brown also writes to get the pain out: “I write with rage.” He creates characters to “make them survive horrible things, worse than what happened to me.” He addresses his addictions directly by making them into a character called Stanley who he can then interact with on the page. Brown says writing makes it all worthwhile. “You need to find the thing you love doing, especially if you need a reason to keep going. Writing helps you enter the zone where your troubles disappear, that’s the sweet spot.”

One of the things about being a disabled writer that non-disabled people often fail to take into account is that the work can take much longer. If you’re capable of working one or two hours a day, an eight-hour job can take all week instead of one day. Harris says, “Time is slower – but ultimately that helps the writing.” Carruthers says, “I am a busy person, but over a longer period of time than some people. I make the time for it to take longer. I value that view, that’s what I’ve got from my disability.”

As with so many aspects of identity, Kiwi writers have changing relationships with the ‘disabled’ label at different points in their lives. There’s a big difference between visibility and identity: visibility is when other people automatically treat you as disabled regardless of your preference, whereas, as Harris says, “Identity is when you yourself name it and acknowledge it publicly.” Brown, for example, even avoided visibility for a long time – tucking his disabled hand into his pocket to hide it, and continuing to drive a manual car. He is still uncomfortable with the word ‘disabled’. “I would identify more as a bit broken.” Hunt, who has been doing disability advocacy work for more than thirty years, says, “You have to integrate what happens to you externally with who you are inside.”

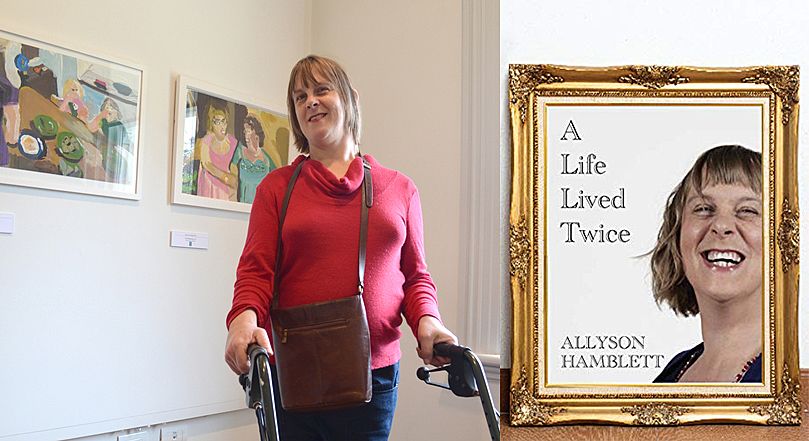

This process is often tied up with other aspects of identity. Allyson Hamblett published a memoir, A Life Lived Twice, about living with cerebral palsy and being a trans woman. She says, “It took me about seven years to write, probably two years of writing and five years of getting the confidence to tell it.”

Speculative fiction writer Andi Buchanan, who is also trans, says, “For me, calling myself disabled and becoming aware of other people's experiences of and ideas around disability was scary, yes, but utterly liberating. The labels that had been applied to me were all negative ones: ‘lazy’, ‘useless’, ‘never listens’, ‘lacks personality’. Understanding myself as disabled meant understanding myself as a person for whom the world made things a bit harder, and that was such a relief.”

Screenwriter Jared Flitcroft (Ngāti Maniapoto), who wrote the short film Tama (2018), says, “I wanted to tell the story about what it's like being a Deaf Māori boy in a small town.” Flitcroft is trilingual, speaking all three of the official languages of Aotearoa (English, Te Reo Māori, New Zealand Sign Language). He says he considers himself very lucky because “I can use these to my advantage when it comes to my writing.” Flitcroft does not identify as disabled. “I don't think of being Deaf as having a disability, because we can do everything except hear to a hearing standard.” Or, to put it another way, being deaf would be no problem if everyone spoke sign language.

Buchanan has also investigated the ways in which one’s environment – rather than one’s condition – creates the disability. They wrote their MA thesis on the ways disability is constructed in science fiction. “I focused on works which portrayed villages, countries, or whole worlds where everyone (or near everyone) was blind, such as John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids, and asked questions about who was disabled and how in those imaginary worlds. I argued that in positioning disability as a feature of our environment, both built and social, the social model of disability invites us to imagine other worlds, how our world could be different. Speculative fiction (that is, science fiction and fantasy) is particularly suited to exploring that aspect of disability.”

Buchanan has published an essay on the theme of universal design. This is the theory that everything, from aeroplanes to book launches to websites, should be designed with all different kinds of accessibility needs in mind from the beginning: not as a favour but as a right. It requires a completely different way of looking at the world.

It’s something we can all start doing now. Kiwi writers have lots of ideas about the ways te ao pukapuka can change in order to be more accessible. Green says it starts with addressing unconscious ableist bias: “People need to realise your brain can be a bit of a dick.” Harris urges editors to actively seek out disabled writers and recognise that there is an audience hungry for work about and by disabled Kiwis. Funding bodies should give weight to applications by disabled people and recognise that their work may take longer – and create scholarships and residencies specifically for disabled writers. When you’re publishing or staging something, consider format: could a person with a print disability enjoy this? How about a Deaf person, or a person using crutches or a wheelchair? If your answer is no, there isn’t the time or budget to accommodate those people, I encourage you to pause and really think about that. What does that say about your kaupapa? How could you make different choices in the future?

If you’re wondering, “But how do I even start?” – don’t worry. Help is at hand. Harris and Hunt have formed Crip the Lit, a movement to raise up disabled writers and their work in Aotearoa. They have run events at three LitCrawls so far, and on 24 March 2019 will publish a free book, Here We Are, Read Us: Women, Disability and Writing, featuring eight disabled Kiwi writers. They urge anyone running literary events to include disabled writers, and to get in touch if you need advice.

Disabled writers can be found in all parts of the literary communities of Aotearoa. We are already creating an impressively diverse range of art but we could be doing so much more. Come find us.

You can listen to Elizabeth Heritage speak about the topics covered in this article with Jesse Mulligan on RNZ.