The Difficult History and Precarious Future of the PACE Programme

Adam Goodall investigates the complicated, contentious history of the Pathway to Arts and Cultural Employment programme.

Amidst a crumbling national arts scene, Adam Goodall investigates the complicated, contentious history of the Pathway to Arts and Cultural Employment programme - a lifeline to some, a tag in a system to others - and asks what it is we're trying to resurrect and why.

Nisha Madhan graduated from Unitec’s Performing Arts School in 2003 and was told to go straight to Work and Income. She’d been receiving an unemployment benefit for two years when friends started whispering, there’s this Work and Income scheme, but it’s for artists and it’s called PACE. An actual artist’s benefit. You had to do battle with your case manager to get on it, but this dragon’s hoard existed.

“I had to fight pretty hard,” Nisha remembers. “I had to show lots of evidence that I’d been to auditions, that I’m a working actor, that I had independently produced shows myself and I’d informally set up a theatre company. I remember it being a pretty dirty fight with my case manager.”

Nisha fought the dragon and won. Her case manager gave in and she was put on the Pathway to Arts and Cultural Employment programme, PACE for short. She got a PACE supervisor, a man named Lynn Lawton. “This guy was fucking amazing,” Nisha continues. At their first meeting, she’d laid out the evidence of her grind yet again and then told him, “Don’t worry, I’m gonna go and do a trial at a café.”

Lynn did a double take. “WHAT? Why are you doing that?”

“Oh, you know, because I’ve gotta have a job.”

“No no no,” Lynn replied. “You’re already doing a full-time job. That’s what this money is for. This isn’t an unemployment benefit.”

“Labour recognises that participating, creating, growing, and achieving in arts and culture are basic parts of human expression and identity,” says the introduction to New Zealand Labour’s Arts, Culture & Heritage policy for the 2017 general election. Released as part of their election manifesto, the policy talks about how it’s important to guarantee “the long-term sustainability of the cultural sector through investment in tertiary education and professional development for artists.” At the bottom of that section, titled ‘Building Careers,’ Labour commits to “re-establishing the Pathways to Arts and Cultural Employment (PACE) scheme.”

Labour mentioned this several times on the road during the campaign – in a press release about their media and film policy, at arts forums throughout the country. The Greens did too: their election policy, untouched since August 2014, commits to “reinstating a financial support scheme for arts and cultural employment administered by Work and Income.”

These announcements might’ve been small, soft, but they rippled through Aotearoa New Zealand’s artistic community. How could they not? PACE is fondly remembered by many as a programme that, from 2001 to 2012, offered vital mentorship and room to grow for thousands of creatives, both well established and just starting out. Also, unless you worked for the opera, the ballet or the symphony orchestra, it’s been a lean ten years for people working in the arts. A potential government that was willing to engage with an underfed, under-loved sector of workers, at least on a base level, was surely better than the status quo.

Was PACE just a tag, redundant and unnecessary in this new decade? And if it was only a tag, why do so many artists want it back?

In January 2012, on the eve of the programme’s quiet death, a Work and Income review emphatically stated that “PACE is not a distinct benefit or programme.” It was – and seemingly always had been – a tag in WINZ’s UCVII client management system. “In addition,” the review said, “a client might also be referred to contracted services targeted specifically at employment in the arts and cultural sector.”

Given that the UCVII system was now ‘non-standard,’ WINZ (in consultation with Creative New Zealand) concluded that it was best to remove the tag and let artists ‘signal their job preferences’ in the new system, JOBZ4U. “It is important that Work and Income communicates,” the review ends, “that the recommendations of this review will not result in any reduction in the level of service that people seeking work in the arts and cultural sectors receive.”

According to WINZ, then, PACE was just a tag, a way of organising people in an old computer system no longer fit for purpose. Yet on May 17 this year, Budget Day, Labour committed to a 10-year strategy to develop our creative sector that includes “the best ways to re-invigorate the Pathways to Arts and Cultural Employment scheme.” So what’s the reality? Was PACE just a tag, redundant and unnecessary in this new decade? And if it was only a tag, why do so many artists want it back?

PACE’s foundations were laid in Dunedin in 1998. Dunedin community arts non-profit The Higher Trust had partnered with Creative New Zealand and New Zealand Employment Services to research and model a series of professional development programmes for artists developing their careers. That work culminated in a report titled A Dunedin Arts Employment Initiative. The report made three core observations:

- That the employment bureaucracy wouldn’t let artists register as artists, forcing them to lie about their preferred career path by choosing hospitality, retail or construction.

- That the Employment Service’s training and development programmes weren’t relevant to artists, as most of them chose to stay self-employed after graduating.

- That there were limited opportunities for professional development for artists, like residencies, internships and apprenticeships.

With some CNZ funding, the Trust began work on a pilot model. The project was led by the Trust’s Project Manager Antony Deaker. Antony’s now the Ara Toi Project Coordinator for Dunedin City Council, developing Dunedin’s creative sector; his LinkedIn profile says, bluntly, “My goal is to help artists (in the broadest sense of the word) make more money.” Prior to joining Dunedin City Council in 2016, Antony spent 16 years as the manager of The Higher Trust and the Artist Development Agency, the organisation that evolved out of the Trust in 2006.

“We created a Dunedin-only register…so that if you were on the unemployment benefit, you could tell your case manager and they would put a flag up against your name. So there we were, trialling and actually validating the arts as a real career option.”

“By the time a policy was being developed in Wellington,” Antony tells me over the phone, “we’d already had some pragmatic progress in Dunedin.” The Trust trialled a series of workshops and programmes, studied examples in Ireland and The Netherlands and developed a sturdy relationship with the Dunedin region’s Employment Service office. “They became problem-solvers with us,” he recalls. “We created a Dunedin-only register…so that if you were on the unemployment benefit, you could tell your case manager and they would put a flag up against your name. So there we were, trialling and actually validating the arts as a real career option.”

PACE was released into the world on 12 November 2001. In a speech three days earlier, Labour’s Associate Minister of Arts, Culture and Heritage Judith Tizard said that PACE would address all of the Dunedin Report’s findings. It would let artists honestly record the arts as their chosen career and it would give them the opportunity to take advantage of professional development that was actually relevant to their work. “It really is an important departure,” she said, “where we can say to young artists, ‘go and get the skills and contacts you need, work on your craft, develop your professional skills, we believe in you.’”

“Now, when you go to Work and Income, you won’t be told to go and work as a dishwasher.”

Martyn Wood, formerly Programme Manager at BATS Theatre and now Assistant Producer for London’s Underbelly Productions, found out about PACE a week before graduating from Toi Whakaari in 2006. A Work and Income staffer had spoken to his class.

“As demoralising as it was that we were actively being encouraged to go on the dole as soon as we were handed our degrees,” Martyn tells me, “it was somewhat heartening to find out that the mythical Artist Benefit, that people I knew had asked WINZ about and been told categorically DID NOT EXIST, did in fact exist.”

Martyn was referred to Standing Ovation, the Wellington region’s only PACE support programme. Standing Ovation was run by Biddy Grant, a performer, director and textile artist, who’d also had a remarkable career as an advisor, administrator and policy-maker in numerous arts organisations across New Zealand. “Biddy acted as kind of a mentor and advisor,” Martyn explains, “I had to call up every couple of weeks and let her know what I was up to.”

“As demoralising as it was that we were actively being encouraged to go on the dole as soon as we were handed our degrees, it was somewhat heartening to find out that the mythical Artist Benefit, that people I knew had asked WINZ about and been told categorically DID NOT EXIST, did in fact exist.”

Biddy was encouraging, Martyn remembers, and they had an honest, non-punitive relationship. Martyn tried as hard as he could to be honest with her; in return, there was no risk of his losing his benefit. “Being on PACE,” Martyn says, “made my aspirations to work in the theatre feel legitimate.”

Martyn estimates that he was on the benefit for less than six months of his post-graduation year. That year peaked with his being accepted into Downstage Theatre’s actor internship programme – six months of full-time, fully-paid acting work.

What Martyn didn’t know was that the programme was part-funded by WINZ. After completing his internship, he met with a case manager so he could be referred back to Biddy and have his payments reactivated. The case manager shot him down: “If I wanted to claim unemployment,” Martyn recalls, “[they told me] I would need to be available for whatever full time work they found.” Martyn tried to explain that he just needed a buffer but he found no sympathy. “WINZ isn’t here to pay you to follow your dreams,” he was told. “You need a proper job.”

The kind of PACE that existed depends on who you talk to. For some, like Nisha and Martyn, PACE was incredibly valuable. It helped them develop their craft and gave them the tools to adapt to being a sole trader or small business owner in their chosen field. For others, PACE got WINZ off their back while they pursued a career they were already prepared to tackle.

For others still, PACE didn’t exist at all. A number of artists told me that their case managers actively denied that PACE existed. Others said they were told they’d never qualify for the programme. The blame for this largely falls on how PACE was managed.

Responsibility for PACE’s administration was devolved to regional WINZ offices. Each region would organise their own Job Seeker Agreements with people who wanted to pursue a career in the arts and each region would independently manage contracts with support programmes. Those support programmes would provide PACE artists with mentorship, support and advice on pursuing a career in their chosen field. This was funded out of each regional office’s baseline budget – no extra money was allocated to make the project work.

“On the face of it, [this regional flexibility] is great,” Antony tells me. “You want regions to respond to their own issues and create their own solutions based on what they see.” But this flexibility also meant that whether or not PACE was actually meaningfully available came down to the regional commissioner and contract manager’s individual priorities.

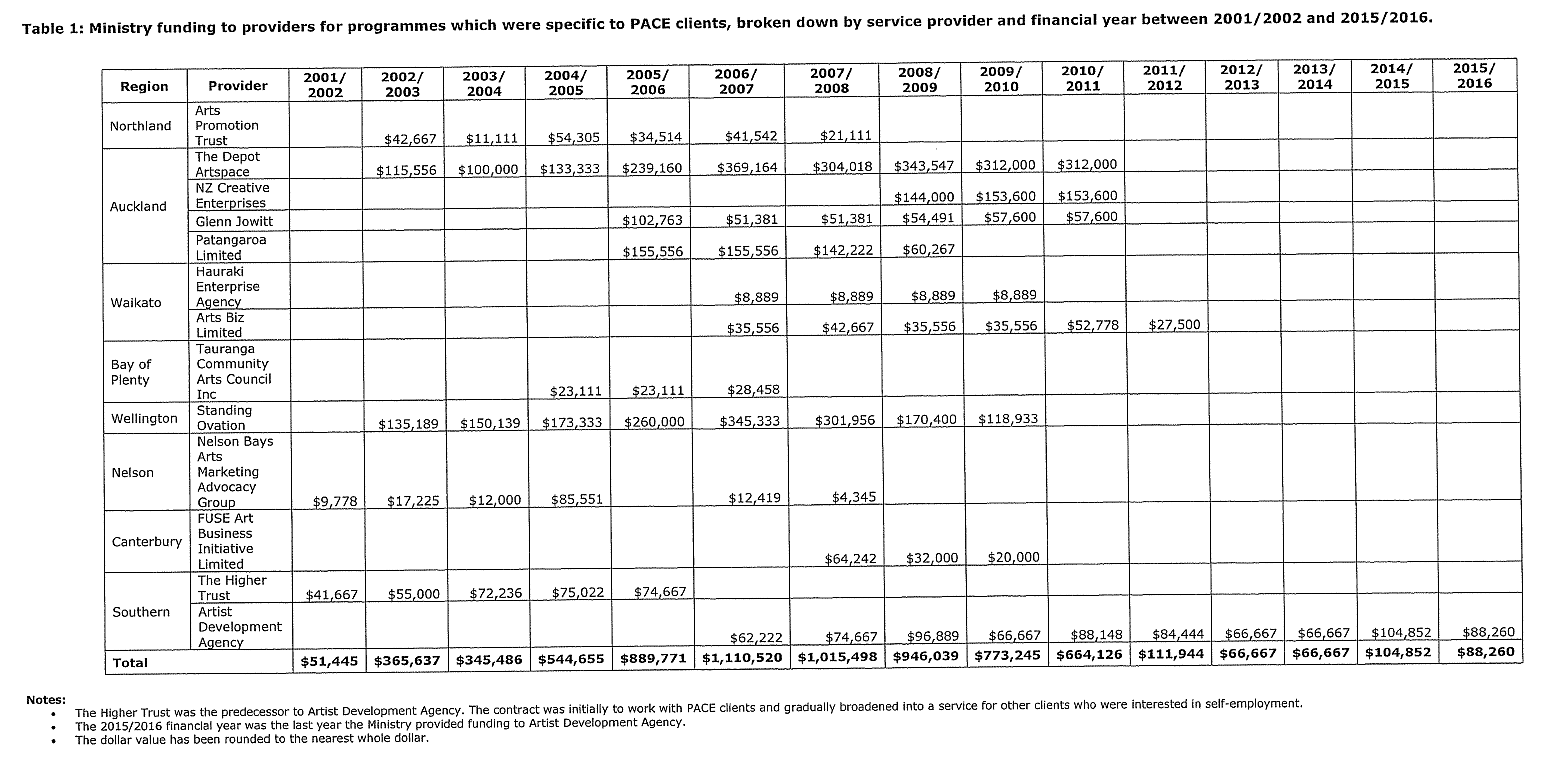

Typically, this meant that regional WINZ staff received next-to-no training about PACE and had very limited resources at their disposal. Of the 11 WINZ regions around the country, only eight ever had contracts for support programmes. Some of those regions picked their contracts up quite late in the game. Bay of Plenty’s only PACE contract, with the Tauranga Community Arts Council, ran from 2004 to 2007. The Canterbury regional office’s contract with FUSE Art Business Initiative also lasted three years, from 2007 to 2010. In each of those years, FUSE was only operating on slightly more than half the budget it had received the previous year.

Other regions had consistent contracts that only covered a small percentage of PACE artists in the region. In Otago-Southland, for example, The Higher Trust’s contract only covered Dunedin City – PACE artists in towns like Invercargill, Oamaru and Timaru were left out in the cold. In a letter he sent to CNZ in 2011, hoping they would advocate for PACE in the face of WINZ’s funereal review, Antony wrote that there was “no useful support for artists in those towns. Many drifted and eventually Case Managers in those offices stopped registering new people in PACE,” he continued. “I imagine this pattern was repeated around the country.”

“There was no centralised commitment to making this work nationally,” Antony tells me. “If there’d been a bit of budget somewhere to run proper training or professional development, you could’ve got a better uptake.” But from the top down, staff at WINZ were paranoid of taking risks and obtuse with people who could have benefited from the scheme. Theatre maker Jo Randerson was an early PACE recipient and found the organisation to be consistently, deliberately unhelpful. “It’s got such an entrenched culture of making things difficult,” she says. “I remember having lots of fights with them, for ages, about how I’d just won the Bruce Mason Playwriting Award, I’d been doing work, and they’d be like, ‘you’re not allowed.’ They’d encourage me to lie.”

“There was no centralised commitment to making this work nationally. If there’d been a bit of budget somewhere to run proper training or professional development, you could’ve got a better uptake.”

Despite WINZ’s lack of commitment, the number of artists registering for PACE surged in those first few years. PACE membership peaked in March 2003 at 2306 people. That June, Minister for Social Development and Employment Steve Maharey boasted in Parliament that 1230 employment placements had been made since November 2001.

The number of PACE recipients fell 88.6 percent over the next four years, to 264 in October 2007, but the Ministry of Social Development also called that a success: the decline reflected, even outstripped, the 78.2 percent reduction in people receiving the unemployment benefit over that same period. “We can attribute most of this change,” MSD’s Manager of Ministerial and Executive Services wrote in August 2008, “to increased job opportunities for New Zealanders during these years.” PACE artists had taken approximately 3399 of those opportunities. Those artists included success stories like Taika Waititi and The Phoenix Foundation, whom MSD bragged about in a 2008 spread for their internal RISE magazine.

The number of ‘clients with a PACE tag’ bottomed out in 2011 at 258, but the writing had been on the wall since 2008. Ministry funding to PACE support programmes collapsed under National, from approximately $946,000 in 2008 to $111,944 in 2011. Long-running contracts with programme providers in Auckland, Wellington and the Waikato were cancelled.

Biddy Grant’s Standing Ovation had helped over 1000 young artists find their feet since 2002, but they weren’t spared the axe. “Paula Bennett became Minister,” Biddy tells me over email, “[and] her focus was totally on unemployed people between the ages of 16 and 18 years.” As a result, Bennett directed MSD to push funding away from initiatives like PACE. Wellington’s regional office offered Biddy a smaller contract. “This was not sustainable for us,” she recalls. “This, combined with some major family events, was the basis for my deciding to stop being a PACE provider.”

In early 2011, Dominion Post reporter Tom Fitzsimons approached MSD to talk about PACE. No one wanted to talk; furthermore, any information the Ministry had previously released was, apparently, “no longer kept.” All the Ministry would do was confirm that PACE was under review. Eleven months later, with CNZ’s support, it was scrapped.

What did we lose when PACE was killed off? “In the long run,” Antony Deaker suggests, “PACE is great because it buys people time. It validates people’s career choices and it buys them time to get grounded and set up again after training.” When PACE was killed off, that time disappeared.

A lot of Antony’s clients came to him post-training – post-art school, post-drama school, post-music or fashion or film school. Many of them lacked the skills to set up sustainable careers. They knew their art, but they didn’t know how to transform it into work. Others struggled with self-confidence, or didn’t have access to capital. “Obviously everyone’s poor,” Antony says, “and so to start a business or a career with sometimes negative capital is obviously a challenge.” Support programmes like The Higher Trust provided mentorship, business advice and access to both work and capital through programmes and entitlements like Taskforce Green and the Enterprise Allowance.

These support programmes also ended up doing a lot of advocacy work. The Higher Trust, for example, worked with education institutions to develop their curricula for teaching students about building careers. The Trust also acted as a go-between for Dunedin’s creative community and local and central government. But buying emerging artists that time to develop and telling those artists that they were worth that time – that was the core of the thing. That was what PACE did best.

“In the long run, PACE is great because it buys people time. It validates people’s career choices and it buys them time to get grounded and set up again after training.”

Biddy agrees with Antony. “PACE worked when people seeking to find a sustainable income in the arts industry were given a little bit of time, with support, to find out how and where they fitted,” she tells me. “For most it was less than a year, but they had to work hard during that time on their future, not their art form.”

That’s not to say that every PACE client found that approach useful. A number of former clients I spoke to were indifferent about their time on PACE: it didn’t give them any new information, or they didn’t feel the urgency to do much more than pick up contract gigs and re-up their payments when those gigs ended. And that’s not to say that all PACE support programmes were good at providing support, either. One former PACE artist told me about the programme in her region, run by a woman who had an art-focused gift shop in the area. When she was accepted into postgraduate study at Elam, the woman who ran the programme was bemused. Why would an artist go back to university?

The majority of artists I spoke to benefitted from the time PACE bought them, though. Even if their case manager or mentor didn’t take an active role in their development – even if they were essentially left to their own devices – that time was valuable, sometimes even critical, to developing their career and their art.

For most of her time on PACE, WINZ left Zia Mandviwalla alone. She signed up for PACE “sometime in the early 2000s,” broke and rudderless after returning from a trip to India. She’d taught herself how to shoot video on that trip, but she’d never really considered the possibility of a career in film. “I didn’t for the life of me know how I could make a career as a director,” she tells me over the phone, “but I knew that I wanted to keep directing.”

Unlike a lot of people, Zia found it pretty easy to sign up for PACE. “I kind of walked straight into it,” she recalls. “Every time I had to go in and talk to the case worker, I would take in tapes of work that I’d done, I’d take in funding applications that I’d made, I’d take work in to be [saying], ‘I’m working, I’m doing all this stuff.’”

“Every so often, I would land a gig to video someone’s wedding and I’d be really upfront about that. It meant that, yeah, they’d cut your benefit because you’d earned money, but for me, it was a way of saying, ‘bear with me, I’m getting somewhere’.”

“Being on that benefit was my film school.”

Zia never had a PACE mentor, either. She doesn’t recall ever being referred on to The Depot Artspace, the Auckland region’s only support programme provider between 2002 and 2005. “No one ever offered it up to me. I’d heard about it, but I never did it because I felt like it didn’t necessarily apply to me. Because I was just trying to be a filmmaker. I didn’t necessarily want to start a business doing wedding videos.”

She used that time to develop her craft and build her portfolio. Not having the money to afford a stall, she would stand outside wedding expos and hand out flyers. She cold-called bands and offered to video their shows – she scored a job recording a Trinity Roots gig at Galatos that way. In 2003, she received $18,000 from Creative New Zealand’s Screen Innovation Production Fund for her debut short Eating Sausage. “I worked really hard at that time.”

Zia’s adamant that those years developing her work, making mistakes and learning from them, were invaluable to her career. “Being on that benefit was my film school.”

There’s evidence now that PACE wasn’t just a ‘tag in the system.’ PACE worked – it helped artists find jobs, develop businesses and build sustainable careers. The evidence is a bit thin on the ground – I got used to hearing from the Ministry of Social Development that nothing was centrally stored and that my requests for data would ‘impair the Ministry’s ability to continue standard operations’ – but it is there.

And now PACE is back on the table. The Ministry for Culture and Heritage has been investigating what form New PACE should take. It’s hard to say at this point what they’ll find: the investigation’s still at a very early stage and will likely involve several other government departments before it’s done. They’re also hamstrung by the same paucity of information: in an early review document titled ‘Initial Thinking,’ an unnamed ministry advisor writes, “MCH and MSD’s data on PACE clients and programme outcomes is relatively limited.”

It’s ultimately pretty hard to escape the impression that, in their attempt to avoid the political risk of spending any money on something that might be seen as a boondoggle, the Labour Government that brought PACE to life not only set it up to fail, but made it that much more difficult to resurrect. That risk of timidity isn’t any less real under this new Labour Government and that’s a problem. When it comes to overhauling government support of our creative industries, PACE can’t be the limit of our political imagination – but it might well be, if it’s set up to fail again.

They’re hamstrung by the paucity of information: in an early review document titled ‘Initial Thinking,’ an unnamed ministry advisor writes, “MCH and MSD’s data on PACE clients and programme outcomes is relatively limited.”

One way to expand that political imagination is by joining the dots between what already exists and what’s currently being developed, linking up different programmes and reforms so that they can work and live together. For example, mooted programmes like Artists in Schools and Creative Apprenticeships, and already-operating programmes like Gateway and Vocational Pathways, can be linked together and used more proactively to provide young artists with vital connections and knowledge. In doing so, Antony Deaker argues, you’d be equipping those young artists with skills that would make it easier for them to build sustainable careers later on.

The artists and advocates I spoke to have a range of ideas just like this, designed to build up and cement both government and private support of the arts. Local government could set up Innovation Precincts; seed funds could be established to give promising arts collectives the money they need to become sustainable; Industry Training Organisations could be set up for the creative sector.

We could also look to overseas projects for inspiration: we could copy Germany’s Künstlersozialkasse social insurance scheme, that gives artists a 50 percent discount on insurance fees, or we could redesign PACE by adopting some of the positives from France’s beleaguered Intermittents du Spectacle system (wherein artists can qualify for uninterrupted monthly payments if they can show they’ve worked for a specific number of hours over a period of 10 months) or South Korea’s Korean Artists Welfare Foundation. We could even take lessons from our own past, like the Project Employment Programmes that helped sustain so many professional theatres in the 1980s.

But these are only small proposals; according to Elise Sterback, Executive Director at Auckland’s Basement Theatre and a longtime arts-sector advocate, they’ll never be the full solution. She argues that nothing short of a radical review of how the government funds the arts will create any change, and that we can’t afford for that review to be a long-term project.

“Where we’re at now, as a sector,” Elise says, “we don’t have the capacity, or the freedom or self-empowerment, to be able to pursue” other means of creating sustainable work and careers for artists. We’re talking partnerships with other sectors, like having artists in prisons or art therapy programmes in the mental health sector; we’re talking business innovation; we’re talking advocacy and community work. “Even if we were given money now instead – here’s all these investment pools for you to come and do that – I think so many artists and organisations would struggle to meet that opportunity.”

That’s because the current funding landscape forces the majority of artists and arts organisations to myopically focus on funding their core work. When the ice beneath you looks like it might give way, you’ve got to get off the ice first before you can focus on anything else. Elise argues that the responsibility for getting artists off that ice lies as much with government as it does with anyone else.

“For a start, we just need more accountability in our sector around [paying the living wage],” Elise offers as an example. “That may look like CNZ...funding people to pay everyone in that project at a living wage, y’know? Because at the moment that’s not a requirement! And I know when artists are completing those, they don’t know...they’re just trying to write whatever the funders want to hear.” That problem is compounded by the amount of money that CNZ gives out at all levels, which is regularly insufficient for covering both an organisation’s core work and a $20.55-an-hour wage for the people who do that work.

“If your goal is to empower artists, putting them on a benefit is not necessarily the way to do that... Burnout’s connected to scarce resources and experiencing poverty through doing creative work.”

PACE simply isn’t a programme that’s set up to create that sort of change, says Elise. It’s a benefit, managed by a notoriously antagonistic and parsimonious government sub-department. It’s ‘problematic’ by virtue of being just that. “If your goal is to empower artists, putting them on a benefit is not necessarily the way to do that,” she continues. “Burnout’s connected to scarce resources and experiencing poverty through doing creative work.”

Artists will choose indefinite poverty if it means they’re being recognised by their communities, Elise explains, whether those communities are local or national. If their work isn’t valued by those communities as vital or at least meaningful to their social and cultural wellbeing, or if that recognition isn’t communicated through financial or social investment, “then that’s what leaves artists feeling pretty impoverished.” “No-one cares,” she continues, diving into that mindset. “No-one thinks what I do matters. Everyone thinks what I do is superficial and indulgent.”

“Any scheme that is supporting or investing in artists or art needs to reflect that,” Elise concludes. “I don’t think a benefit does.”

The biggest problem that any new PACE programme will face is one that it won't be responsible for and cannot possibly solve. It’s the problem of being a microcosm for our broken national dialogue around the value of art and the artists who make it.

“There needs to be a big shift in the way that art is considered in New Zealand,” Nisha Madhan tells me over the phone. “It’s sort of in-between. We’re not like somewhere like Berlin, where they think art is intrinsic to their life and their social wellbeing and culture...we sort of have that but we also have the other side, where we’re a bit like Australia, where we’re like, ‘it’s just entertainment and a commodity.’ We’re between the two things, and the commodity side has gotten a lot of press.”

“We continue to really love that narrative, the Flight of the Conchords narrative,” Nisha says. “We haven’t supported narratives that are alternative to, ‘I made this thing here and then I blew up overseas’.”

That’s exemplified in the political shitfights over the last PACE. Consider, for a second, Question Time on 18 June 2003. Labour Minister for Social Development and Employment Steve Maharey is asked a patsy question about PACE and responds at length, talking about job numbers and how PACE is helping build our economy. Industry New Zealand reports that our creative industries contribute around 3.1 percent of New Zealand’s GDP, etc. etc. In response, representatives from National, ACT and NZ First take aim, criticising the government over the unworthy acrobats and stuffed-toy-makers on PACE and the ‘insignificant’ art that they create. ACT MP Katherine Rich bellows across the floor, “Why does the Minister think that handing out a bunch of Government pamphlets will do anything to create the next Michael Hight, Stanley Palmer, or Grahame Sydney?”

“We continue to really love that narrative, the Flight of the Conchords narrative. We haven’t supported narratives that are alternative to, ‘I made this thing here and then I blew up overseas’.”

The vast majority of artists I spoke to about PACE found it helpful, valuable, even critical in shaping their career and their art. But PACE also did a lot to normalise that ‘commodity’ narrative on a national scale, in part because the other side of the political debate refused to acknowledge the worth of supporting emerging artists on a social and cultural level.

From the RISE magazine spread on up, the government played into that image. They justified PACE as a job creator, a way to match ‘cultural workers’ to the work they were best suited for. When she introduced the programme in 2001, Judith Tizard balanced her talk of the arts being ‘intrinsically good’ with a more familiar analysis of the arts as an export with a lot of potential. “In a globalising world, it is important that we continue to tell our own stories,” she said. “If we don’t know who we are, how as a trading nation do we know what’s for sale?”

That commodity narrative was expressed in PACE’s structure – it was cost-neutral, decentralised, a benefit programme established under a Third Way government that thought a ‘cradle to the grave’ welfare state was an “inadequate model for today.” That structure undermined PACE just as much as it gave it life. It made PACE a stand-in for a greater debate over the worth of New Zealand artists and the role that the government should play in supporting them. It was a debate PACE was doomed to lose.

So what should a new PACE look like? How should it be treated? If there’s one thing that’s certain, it can’t stand alone. It has to be one of many parts of a revolution in how the arts are supported in Aotearoa, one that focuses on the artist as an artist rather than as a contributor to our gross domestic product. One that recognises their work, that values their contributions to our communities and that refuses to accept poverty as a price they have to pay to be able to do their work.

“PACE should be seen as a framework that does actually live up to the idea of a pathway,” Antony Deaker tells me when I ask him what this new PACE should look like. “It’s a 20-year pathway, not an 18-month pathway inside WINZ.” PACE can’t cover the rest of those years. It can only be the start.