Deep Cuts: A Response to A Short Run

Fans, dreamers, punks and ravers, this one's for you. Kerry Ann Lee revels in the history and design of the lathe-cut record in this fun response to A Short Run at The Dowse Art Museum.

Fans and dreamers, this one’s for you. A Short Run is a detailed look into underground/experimental/noise music publishing in Aotearoa through graphic artefacts such as lathe-cut records and album covers. Researched and curated by Luke Wood, this exhibition, currently on at The Dowse Art Museum, presents a constellation of music-makers and artists who made their own limited-edition lathe-cut records and successfully released them out into the world. The exhibition shows off the prolific audio-visual output of sonic pioneers, graphic agitators and noisemakers in Aotearoa, via hundreds of records on loan from the private collections of artists, musicians, bands and small independent record labels around the country.

I crawled out of my social slumber to visit The Dowse on the morning it reopened after being in its own cryogenic state, closed for nearly two months due to the nationwide lockdown. My musings began in isolation, drawing on memories of the show from when it launched at Objectspace in Auckland last year. As I entered this version of A Short Run, chiming, ebbing, chirping and rustling from audio speakers in the gallery woke up my ears and warmed up the space. The soundtrack segued to a favourite tune of mine: “Sleep Walk” by Santo & Johnny, as covered by none other than Wood’s band The Opawa 45s.1 Oh, sweet serendipity.

Being in this room full of records appealed to my own archival impulses. Each one is a world unto itself, as well as a signpost to other records, worlds and scenes. The large-scale display system elegantly shows the works recto and verso, allowing viewers to get up close and personal with record sleeves and discs, with paper labels on both sides. The accompanying floor schematic and catalogue is useful in reading and navigating the show.

A Short Run, The Dowse Art Museum, 2020. Photo by Kerry Ann Lee

When making music, choosing the format is the definitive first step. Whether it’s a cassette tape or a digital release on Bandcamp, you have to point to the artefact – the physical thing – so decisive choice-making is essential. Your work needs to look and sound this way and not that way! Late last century, our pre-digital recording options were limited to cassette tapes and, later, compact discs. Vinyl record pressing was not readily available here – hence the lathe cut.2 Lathe cuts have the audio directly etched or engraved into the discs in real time (not pressed like vinyl), and are playable on regular stereo turntables. This technology has existed since the 1880s and it was as recently as the 1960s that you could walk into a recording studio in New Zealand to cut your own music to disc.

The idea for A Short Run arose from conversations between Wood and Objectspace Director Kim Paton in late 2017. They began talking after the gig launch for the 12” record Visceral Realists by Wood and Bruce Russell (founder of the influential Xpressway and Corpus Hermeticum labels, and member of the band The Dead C). Going through Russell’s back catalogue the following year further crystallised the project for Wood, who then spent a long time visiting people around the country who had run labels at various points, collecting research material. Faced with the sheer deluge of archival content, he decided to focus his research and curating on the records and their cover art; “total artworks”3 that were collaborative in nature – musicians, artists, illustrators, graphic designers, engineers and label distributors are all present here. Often it was one and the same person.

A Short Run, Objectspace, 2019. Photo by Sam Hartnett

Many of the records featured in the exhibition were made by Peter King, who had been operating his service in Geraldine since the late 1980s. He created small runs of records, from ten to 100 copies, through a process of individually cutting transparent polycarbonate discs using four disc-cutting lathes. These records were cheap to produce and appealed to artists who favoured more tactile and experimental approaches to their sound and art-making. King is present in this exhibition in a video, going through the motions and working his magic. Discs are spinning. Discs are etching. Droning guitars playing through the gallery’s speakers enhance this meditation. I see green pastures outside his studio window. Cleaning. Playback. Plastic sleeves. Bagging. Banging. I know those drums. The tunes of Hex Waves kick in.

The lathe-cut record was the stuff of teenage dreams come true. I first heard about Peter King in Geraldine from my penpal Liz Mathews, back when we were writing letters and trading zines and mixtapes just out of high school. The perennially cool Crawlspace Records in Auckland put out a lathe-cut record for her band Goldifox, which was sent to people far and wide, including people in known bands and labels overseas who were big fans of New Zealand indie music. Years later, she revealed to me that they actually made a ‘picture disc’ – there was a colour photocopy of a painting their friend had done, sandwiched between the two clear plastic sides of the record!4 This format also appealed to friends in and around the hardcore punk scene during the mid-late 90s. It had its own sound that was different to vinyl and was said to wear down quicker, yet the lo-fi analogue format had integrity in the same way that much-loved photocopied fanzines get tatty the more they move between friends and punk houses. It’s a glorious thing.

A Short Run, The Dowse, 2020. Photo by Shaun Matthews

A Short Run exposes such earnest ambitions and can poetically draw us back to the local. When I wasn’t busy writing to Liz in Kerikeri, I’d train out to The Hutt to hang out with friends who grew up there. They would organise punk gigs in community halls and house-party shows in suburban garages. Art and music were survival tools to push back against the boredom and conformity encroaching all around. So who would have ever expected to see the split 8” recording by local hardcore punk bands (and Lower Hutt SK8 Posse darlings) Diecast on one side and Loosehead on the reverse, a quarter of a century later on display at The Dowse, located in the heart of what once felt like the very real teenage wasteland that was the Hutt Valley.

These artefacts are made possible through mutual fandom, late nights, shared obsessions, band vans, good fun, tinnitus, tears before bedtime and the great lure of the local. As many of the artists were unlikely striving for greatness in that public “Look-at-me!” kind of way, it’s meaningful to encounter this work in a major national art museum. Luke admits, “I kind of wish the music I liked did have a bigger audience. If anyone went to the show and discovered they loved listening to 20 minutes of feedback then that would be great!”5

A Short Run, The Dowse, 2020. Photo by Shaun Matthews.

A Short Run could be the antithesis of a Rolling Stone magazine survey of Hot Top 40 Best Album Art. Not only are these works bona fide tactile objects, the album art is unique. In the exhibition, vitrines display intricate hand-cut 3D dioramas like those by Little Skull – sculptural and oddball formats – while those encased in the main frame are like bugs in amber that attract the viewer’s eye towards an improvised sensibility in fabrication.

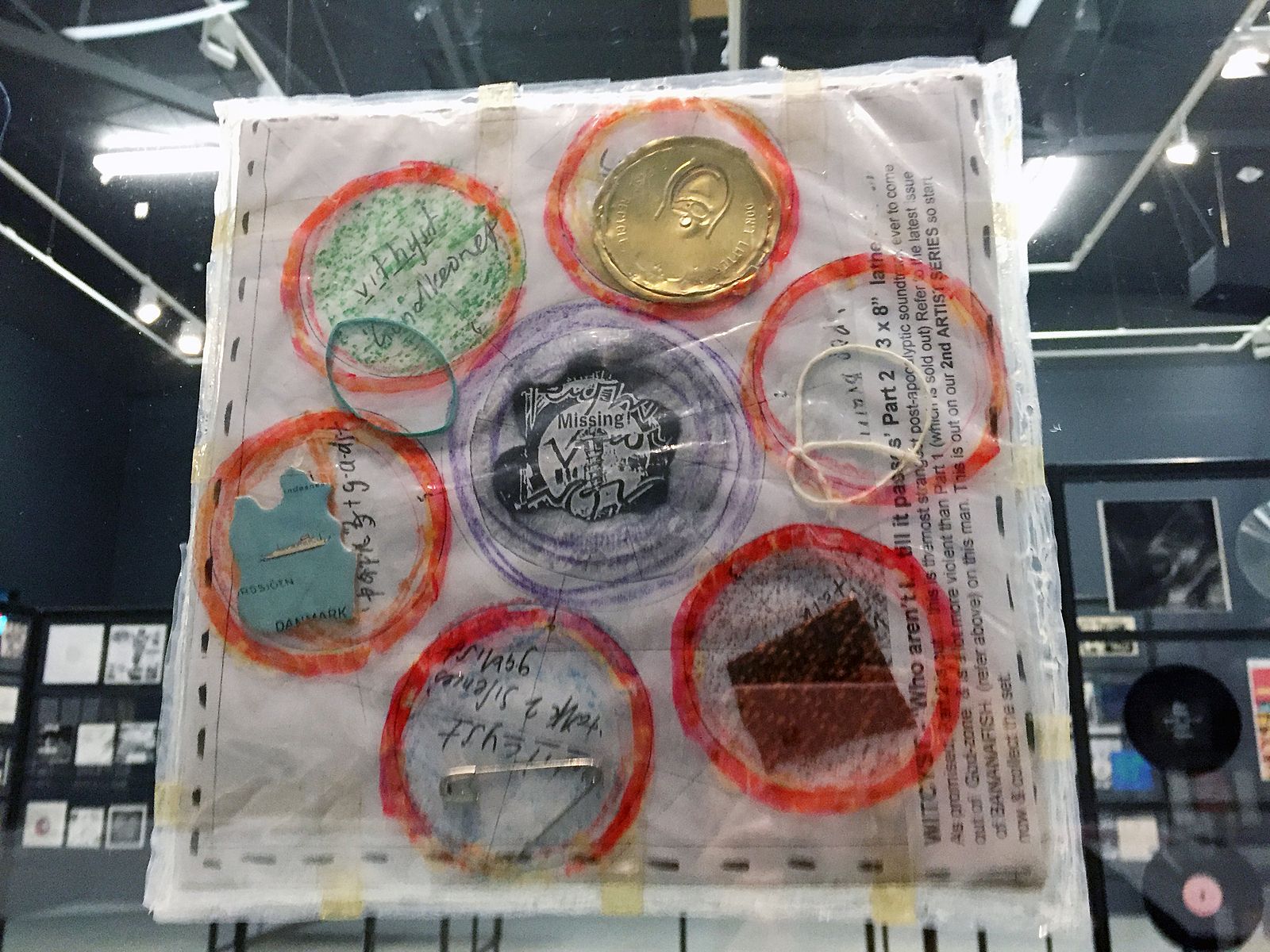

Prized specimens in both the ‘Finding’ and ‘Recycling’ sections of the exhibition include record art made by Witcyst, Beth Ducklingmonster, Stefan Neville, Alan Holt and Stella Corkery. These excel as rip-shit-and-bust graphics, crafted using found debris glued or stitched over the top of silkscreened plastic junk, messed-with bargain-bin record sleeves, spray-paint stencilled wallpaper, bits of fabric, cheerful-but-seedy old packaging and assorted doodads. These unique assemblages show the raw power of graphic design beyond tired style guides and played-out visual effects.

Witcyst record in A Short Run, The Dowse, 2020. Photo by Kerry Ann Lee

Records are a form of cultural currency that (along with fanzines, t-shirts and patches) is crucial in sustaining underground communities of interest. I was reminded of my days of folding and stapling stolen photocopied record inserts and gluing tabs, to suddenly notice a spelling mistake on the cover, or a major misalignment with the home-job gatefold covers. Incendiary slogans (cuss words!), foldout posters, stickers and lyric sheets featuring band logos that would later be traced and stencilled onto the back of someone’s jacket or guitar case. Heartfelt, urgent and defiantly independent. Feelings so vital for a young designer. These markers of identity could make us appear much larger than we actually were, when in reality we were just bored, weird kids obsessed with making these things that would connect us with other bored, weird kids before life online. Some of these records might have spent time gathering dust in storage boxes under beds around the country, like so many bedroom distros I know of. Moving units was never a driving force to get out of bed for. Yet pipe dreams like making your own records (and sometimes actually doing so!) somehow did. So in that way, the exhibition offers a moment of fulfillment in the creation of these works.

A Short Run can be read as a survey of sonic arts in Aotearoa, and the way this is realised through vernacular graphic design, the influence of which is evident in Wood’s own creative practice. Of particular interest are the scale of production and the politics of the small run – a limited edition with a limited supply. “This is really significant given the times we live in,” says Wood. “As someone who longs for the collapse of Western society, these things are like talismans of what art could look like in the future!”6

Artists making their own records from scratch is not new, but reflects a particular anti-capitalist attitude. Writer Francesco Spampinato also suggests that we should consider the systems of representation around artists’ recordings – the alternative forms of value and exchange that relate to concepts of relational aesthetics, as theorised by Nicolas Bourriaud – as a response to the alienation caused by the emerging digital culture of the 1990s.7 Contemporary art needs to be presented as tangible, real moments to be lived through.

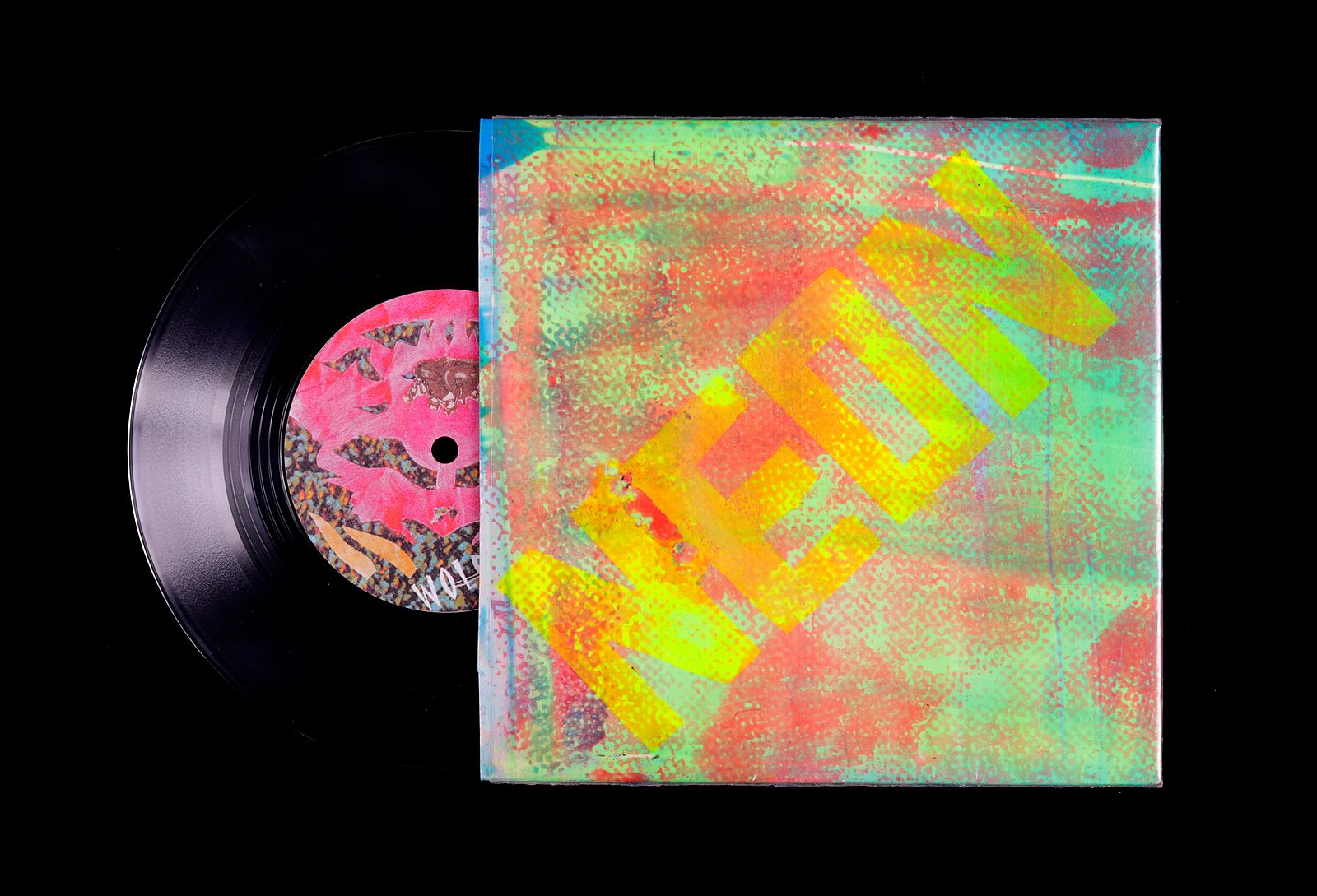

Wolfskull/Rise of the City Cat Cult, Neon, Root Don Lonie for Cash, 2010. Cover art by Georgina May. Lathe cut by Peter King

Although some bands and artists documented in A Short Run found varying degrees of acclaim, lathe-cut technology afforded equal opportunity for nascent upstarts and total amateurs. The affordability and accessibility of the medium enabled people to bring their genuine selves into designing, from concept to cover. The portability of the format encouraged artists to customise their own distribution channels, to find audiences and collaborators both locally and internationally.

Here’s a fun fact: Peter King once met Rick Rubin at Christchurch Airport to pick up masters to cut a record for the Beastie Boys – a big run of 1420 copies of Aglio e Olio for Australian label Fellaheen.

Many of the creators of these sonic artefacts hail from small and lively music scenes with histories that ran parallel to one another, sometimes cross-pollinating and creating their own orbits and lines of flight.This includes people like Michael Morley, Alastair Galbraith, Campbell Kneale, Stink Magnetic, Lovely Midget, The Futurians, Violet Faigan, Julian Dashper, Clayton Noone, Thee Strap-Ons, Wolfskull, The Aesthetics, Pink Air, End of Alphabet Records, Samin Son, Tourettes, Aldous Harding, Eye, Death and the Maiden, Surly, Trinity Roots, Lee Ranaldo and many others.

Although Peter King is a pivotal figure in the show, Wood has taken care to present his practice alongside others with skin in the lathe-cut game, like electronic music pioneer James Meharry a.k.a. Pylonz (In Real Life) and Johnny Electric, who documents his work with his custom-made lathe set-up via The Secret Society of Lathe Trolls, an online “forum devoted to record-cutting deviants, renegades, professionals & experimenters.” Both are Christchurch-based, confirming my long-held suspicion that Te Waipounamu is a special sonic place.

A Short Run brought me back to what is real and good – life as an enthusiast. The past few months have been spent living way too much both online and inside my head, and walking around the empty streets forlorn, really missing live music. The last gig I went to on a whim was Stereolab some months (which felt like years) ago, mostly to see my pals Caro and Martin, who came up from Dunedin for it. That too felt like a dream. Music is the salve that brings comfort in troubled times like right now. It revitalises and can help us feel bigger and braver than we actually are. Records remind us of this. Outside of dominant market forces, these are rare and precious talismans of the future, showing what is wildly possible working at a small scale here.

A Short Run: A Selection of New Zealand Lathe-Cut Records

Curated by Luke Wood

15 Feb 2020 – 7 Jun 2020

Feature image: Purple Pilgrims, Purple Pilgrims, PseudoArcana, 2011. Cover art by Purple Pilgrims. Lathe cut by Peter King

1 The Opawa 45s, “Sleepwalk ‘17” (from Sleepwalk ‘17/Bullwinkle |||, Ilam Press Records, 2017, lathe cut by Peter King).

2 Amos Mann, in an enthusiastic Facetime conversation about analogue recording formats with the author, 8 May 2020.

3 Luke Wood, Facebook correspondence with the author, 12 May 2020.

4 Liz Mathews, Facebook correspondence with the author, 19 May 2020.

5 Luke Wood, Facebook correspondence with the author, 18 May 2020.

6 Ibid.

7 Francesco Spampinato, Can You Hear Me? Music Labels by Visual Artists (Eindhoven, Netherlands: Onomatopee 109.1, 2015), 20.

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with The Dowse Art Museum, which covers the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.