Death of a Celebrity Crush

When Soong Phoon was twelve, she fell in love with Natalie Portman. Over a decade later, the relationship in tatters, she asks what makes our celebrity infatuations so intense, and what cuts them so ruthlessly short.

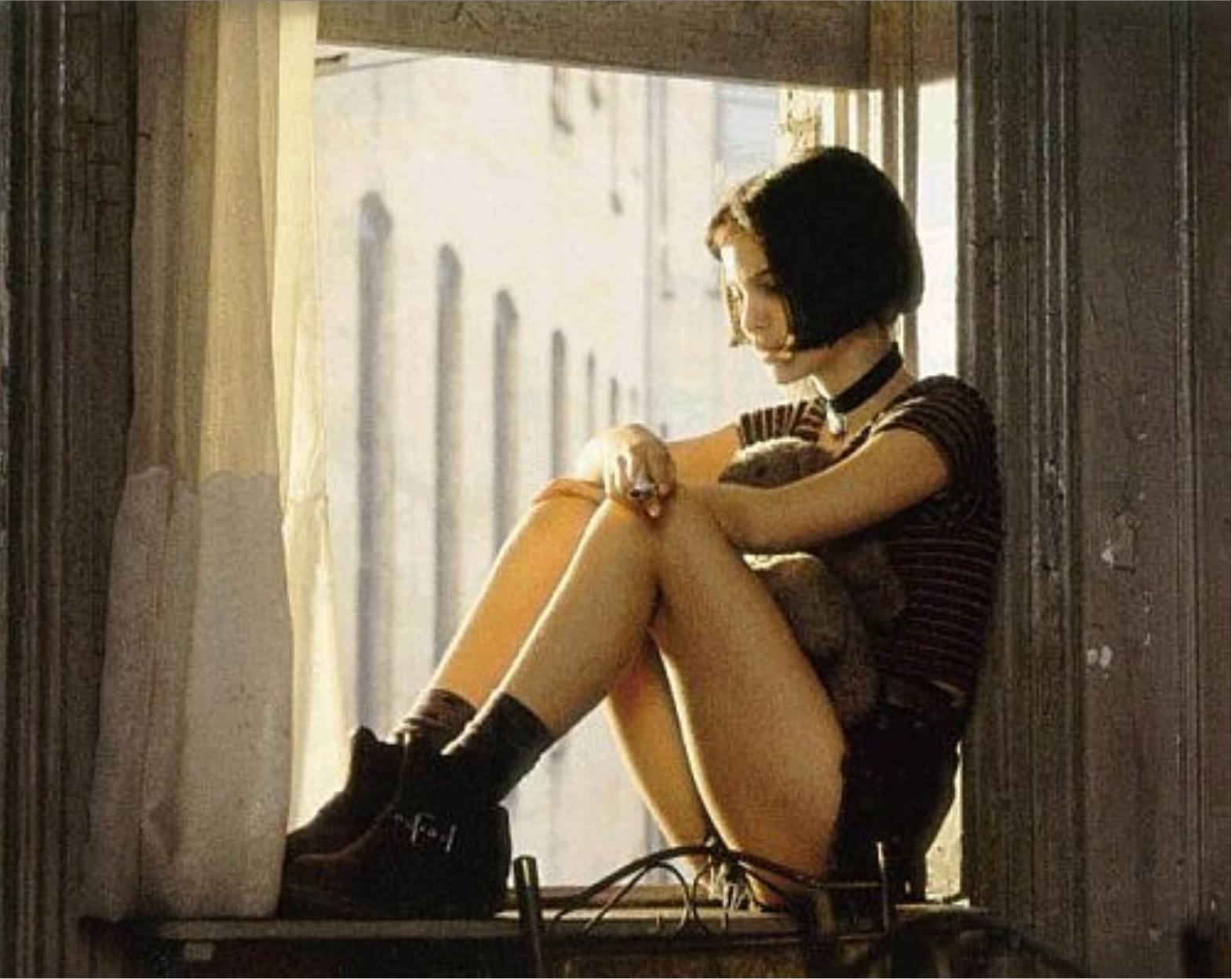

When I was twelve, I first saw Luc Besson's Léon: The Professional, and I fell in love with the eleven year-old Natalie Portman. Months later, when I gazed upon her as a sulky White House brat reading Herman Hesse's Siddartha in Mars Attacks, it intensified. When she announced she was putting her acting career on hold to attend Harvard, advocating the importance of education in all her interviews, it escalated even further. I own around forty magazines on which she's the cover girl. My teenage savings from a paper route were allocated to purchasing these as they came out. I would celebrate her birthday every year (9th of June) – once, my aunt made me a cake for her birthday, and we sang Happy Birthday her. And when she started smoking, I started smoking.

Celebrity crushes are peculiar things. Without ever forming the building blocks of friendship, romantic relationships and family that dictate the emotional responses in our lives, they’re able to affect us in visceral and visible ways – tears of joy, of grief, love (clearly) unrequited and intense, near-palpable daydreams. And like those other relationships, we can cut them savagely short – lose our interest and our desire for those beloved from afar.

Was my yearning actually an affliction? In 2013, the British Journal of Psychology conducted a study on 600 individuals and diagnosed a third of them with this very particular disease: ‘Celebrity Worship Syndrome’. Our celebrity crushes have evolved into an official clinical diagnosis – possibly not DSM material, but mortifying enough who anyone who thought they’d grow out of them as teenagers. I entered my twenties and my kowtowing worship continued. I was absolutely certain that one day, she would get the Oscar she well deserved.

When Darren Aronofsky's Black Swan was finally released in New Zealand, I was feverishly, insanely excited, yelling 'This is it! This is it! She's gonna get it, FINALLY!' Friends told me to calm down. They had to hold me down in my seat to prevent me from standing up, cheering and screaming in sheer joy at the end of the film. And then, she won the Oscar.

And then, she gave her speech.

It was many things. The mantric assertion that she was a 'good human-being'. The even-keeled smugness with which she handled all the press surrounding the film. The announcement of her pregnancy. My crush face-planted. I beheld her with sudden, burning contempt. After fifteen years of faithful loyalty, even through the second Star Wars trilogy, one small (but immensely irritating) thing turned my love to hate.

In 2011, pondering these phenomena and their untimely ends, the University of Auckland’s Dr. Pansy Duncan published an article entitled Corey Haim and the 'homeless celebrity': rock bottom on Rodeo Drive in the journal Celebrity Studies. She referred to our experience as the ‘meltdown’ of our 'celebrity relationship …the soiled spectacle of celebrity gone to seed.' Duncan focuses on former child-star Haim, whose progress from 1980s teen pin-up to poster-boy for celebrity homelessness was notorious. In the article, Duncan suggests the reaction is mutual, even if the stars never have an individual sense of us - that each decline in the public eye incites a response from a celebrity, ‘the pathos of a man (or woman) who is still waiting for the camera to confer its special, celluloid shimmer; who still trusts in celebrity’s beneficent embrace; who is still half-expecting to be ray-beamed from public contempt and into the celebrity starship once again.’

Back on our side of the equation, some social commentators suggest that we extract some kind of perverse pleasure from the collapse of our celebrity obsessions: their loss of cultural capital, the realization that they are humans, just like us, that make mistakes. Tellingly, their fame won’t save them from the kind of moral judgments we might hold back on with friends and family: one reformed Jennifer Lawrence fan recounted to me how she interpreted a comment Lawrence made about Katniss Everdeen (the primary character in The Hunger Games) as being 'like a male hero with a vagina' as sexist enough to immediately drop her cold. And our aesthetic judgments are if anything even tougher – seeing a friend’s dismal open-mic singer-songwriter night won’t make us ditch them, but a lapsed Robert Pattinson-obsessive I knew said the end was ultimately exacerbated by his attempt at a singing career.

If we do end up in the same room as them, the same fickle and awful judgments we cast on complete strangers can ensue: an intensive Entourage viewer finally saw Adrien Grenier walk past her at the Civic Theatre in Auckland, and realized what a 'short-ass' he was - it abruptly ended her crush. And we project, project, project. One friend managed to hold down consecutive (and platonic) crushes on Kimbra and Lorde, but once they broke into rapturous international success, they fell away. It was as if they’d drifted - as if people who had never known he existed suddenly weren't prepared to make the time of day anymore. Geographically, this actually seems to be a particularly Kiwi syndrome.

As to when the crush begins, American film critic James Monaco writes:

‘Before celebrities we had heroes...Now, what these hero types all share (are) qualities that somehow set them apart from the rest of us. They have done things, acted in the world: written, thought, understood, led. Celebrities, on the other hand - needn’t have done...anything special. Their function isn’t to act - just to be...The qualities of our admirations are distinctly different, and the actions of heroes are often lost in the haze of fictional celebrity unrelated to nonfictional heroism...’

Are our crushes a confuzzled mish-mash of the fictional and the (sometimes apocryphal) real-life behaviours of our idols? Is it a (mostly) harmless, minor form of disassociation?

It’s probably not a recent malady. Cultural studies academic Graeme Turner’s Understanding Celebrity references historian Daniel Boorstin’s assertion from the 1960s - half a century ago - that the fixation with those famed and fortuned represented a ‘fundamental inauthenticity’ in American culture and ‘the end of civilisation as we know it.’ Since the 1920s, Turner notes that more than fifty percent of the stories on biographical interest in popular publications were on those from the entertainment industry. This was a shift from the early 1900s where the primary focus was on those from ‘politics, business and the professions’. Was this a loss of interest in our ‘nonfictional’, legitimate heroes, as well as real interpersonal relationships?

Closer to home, I turned to an academic specialist in Celebrity Studies on the subject (the academic asked not to be named in the interview - and given that academia reproduces certain hierarchies of celebrity even as it purports to be beyond them, that's perhaps for the best). The lecturer’s view on the occasionally venomous ends to our celebrity infatuations are that they're little different to any other crush that sustains itself as exactly that (rather than, say, an actual relationship). “It's just about, boringly, an ideal self - on a private level - and self-definition on a social level, now projected onto an external celebrity object, who serves as 'aspirational' and as a model of desired self-actualisation for the actual self.”

Like psychoanalyst Heinz Kohut suggests, this is part and parcel of every individual's narcissism, the 'external object' they require to 'complete' themselves. When this celebrated and idealised object disappoints us or fails in some manner, this completion collapses - it's as if a combination of the seeming failure of the celebrity crush and a disappointment in one's self as the external object has been internalised.

And it truly is a creepy thing, that, well, mostly everyone seems to do. Our celebrity ardour constitutes (sometimes, but most definitely in my case) a desperate tracking of their every move that it’d be difficult to condone doing to someone you actually knew. But haven’t we always ‘fallen in love’ with ‘strangers’? Isn’t that just what happens in everyday life? My academic’s view is that “...ultimately everyone is always a “stranger”. How can you ever really, truly know what exists in the very heart, within the interior of an Other?

“I don't agree with the fundamental premise of most celebrity studies: that there's something uniquely modern about celebrity worship," she says. "The public have admired famous people from afar since the advent of cinema, particularly since the Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Clara Bow-era in the twenties. I would assert that there’s nothing unique about the kinds of investment that we bestow upon these people. Like any other investment it's a big disastrous jumble of envy and longing and frustration and resentment."

A dazzling image of supposed ‘perfection’ appears on one’s screen, one’s laptop, one’s phone. Charming, charismatic, picture-perfect. Could this be ‘the one’ that fills the ‘void that exists at the centre of being’ that Freud referred to? It’s the image of an Other, of what appears ‘to be’ before us; we subscribe to this ‘one’, this Other, because he/she fulfills us in some form or another. It’s the immediacy of the aesthetic, and once we discover more – a ‘more’ which is usually a product of press-coaching – we’re well and truly seduced. But then, a clumsier process takes place in real life - the object's reactions are just a little less staged, our approach more cautious.

So why do some commentators still, like Daniel Boorstin once did, lament it, and insist that this kind of fixation signals the ‘end of civilisation as we know it’? An investment in a celebrity, a sportsperson, a news presenter or an author is really no different from a crush on someone that lives in the flat across the street, or someone that’s on the same bus route as you every morning. We are always susceptible to those that are inaccessible, or those unavailable, because there’s a mystery (and a very low level of risk) in that cocktail of social investment. Who isn’t interested in attempting to know the unknown, or deciphering it? Isn’t that just part of getting ‘to know’ someone in a regular interpersonal relationship? The fact that we’re now given unprecedented options and avenues to decipher the famous unknown is just an added sweetener.

Perhaps our investment in celebrities and our scrutiny of their so-called ‘lives’ (as mediated by tabloid news) is just an extension of older forms of social bonding/gossip, calibrated for a big, fragmented, industrialized and globalized society. The lecturer suggests that “just as we used to chat about Joe Bloggs from down the road with our neighbours, celebrities serve as a touchstone of commonality within the wider pool of people we're likely to come into contact with these days. That's why I find celebrity culture relatively innocuous, even benign - it seems so much more about social connectedness.”

Is there a downside? Maybe, the lecturer suggests, in “the way certain forms of celebrity makes people question the value of their own lives through aesthetic and financial comparison. Even something like being able to afford plastic surgery, I mean - maybe it was better when our gossip circulated around Joe from down the road than around Brad Pitt in his French villa.” And then there’s the point where the obsession bottoms out for us, personally. According to Kohut’s theory, because of the intensity of our fixation on the external object - now an internal, integral part of the adoring subject – the eventual consequence is the need to reject and project the internal, self-directed hatred externally once again (boy, do I know about that). It’s no longer just self-loathing and interior disappointment – we foist it relatively harmlessly on someone else.

Perhaps it’s an inevitable process. So much of what we view as celebrity fuckups tend to be extra-textual to their press and media-coaching. It’s where or when they go off-guard, or off-message. We even break the spell ourselves through our voyeuristic tracking of their every move and their history, enabled by the multiplicity of online platforms and repositories of their activities. We can Google until something incites us to hate.

On the other hand: we see Jennifer Lawrence trip up the red carpet and lose all her grace in a moment, and she charms us. I find Leonardo Di Caprio’s exclusive supermodel rule on potential dates hilarious and even see it as a poignant stopgap for his unattainable Oscar. I hope no one’s self-serious enough to still be getting worked up about Kanye West being ‘uppity’ or ‘arrogant’. So these seemingly exterior, unintentional moments can go either way, reinforcing or smashing the vase upon our mantelpiece of infatuations.

It's still seems bizarre that a choice, an unintentional reaction, a perfectly normal, everyday thing to do, can crush our expectations of what these people mean to us. It’s not Portman’s fault, but no crush was ever meant to weather the amount of access, scrutiny and Internet-baiting encouragement to pass judgment that a celebrity crush has to. Imagine liking someone you met one Friday night in Auckland and suddenly being able to uncover out enough of their dirty past and despicable philandering to absolutely Hiroshima them in a single weekend. At this stage, we can’t – and in the meantime, a celebrity crush is a lot of fun and satisfies us. It completes us in some manner, even if it eventually ends. So you reel, briefly, and then find another one. I’m really sorry Natalie, now I’ve got Lupita.