Dashper the Friendly Ghost

Emil McAvoy reflects on Julian Dashper's presence at the recent CIRCUIT symposium, 'Phantom Topologies', in Wellington.

Emil McAvoy reflects on Julian Dashper’s presence at the recent CIRCUIT symposium, Phantom Topologies, in Wellington.

Friendship wasn’t incidental to his project, it was his medium.

– Robert Leonard, Julian Dashper & Friends

Julian Dashper once told me I should have my own TV show. At the time, I was at art school, and his implication was that the show would constitute an artwork. He also floated the idea of sharing a pizza as art. “And hang the empty box as an ‘oil painting’?” I asked. “No”, he replied, “We’d just eat the pizza.” Long before the terms ‘relational aesthetics’ and ‘social practice’ emerged, Julian understood art to be something fun that people did together.

I considered Daspher a mentor and felt a personal connection to him. I also know he was an influential figure to a number of young artists. He passed away in 2009, after a battle with cancer bravely fought in the public sphere. In their personal discussions of Julian, people seem to focus on his charisma and warm, generous spirit. And for good reason. Beyond the material traces of his work and his enduring artistic influence, he lives on in the way he made others feel.

Dashper’s presence loomed large at the recent CIRCUIT symposium, Phantom Topologies, which grappled with an ambitious range of concerns, attempting to situate the work of Aotearoa-based film and video artists in a global context. The symposium was hosted by City Gallery Wellington, whose Senior Curator, Robert Leonard, recently mounted Julian Dashper & Friends, a survey that placed Dashper’s work in conversation with that of a number of other local and international artists. Like that show, Phantom Topologies sought to respond to Dashper’s artistic legacy. Among its extensive programme of exhibitions and events was a series of commissioned films responding to Dashper’s writings and video works.

Mark Williams, director of CIRCUIT and co-curator of the symposium, spoke about the duality of proximity and distance at the heart of Dashper’s work, along with his interest in the social architecture of arts organisations. Guest curator George Clark, a United Kingdom-based writer, artist, and independent curator, described Dashper’s interest in locality, distribution, and geographical specificity – the way he inverted New Zealand’s oft-cited “tyranny of distance”, viewing its peripheral location to the artistic centres of Europe and America as a form of introduction.

Further, Clark asked what it might mean to consider the interdisciplinary Dashper as a video artist, leaving the audience left to ponder the implications of the proposition. In an interview for the CIRCUIT CAST podcast with critic and curator Mark Amery, he suggests:

In some ways they [Dashper’s videos] are significant because they are often not seen as central to his practice, and so it gives an opportunity to … look at his practice … from the other end of the telescope to … say, what would film and video practice look like in New Zealand if we were to say Dashper is a video artist? How would that re-navigate and re-orientate the way that we could understand art history and different types of work with video?

As part of an associated artist week, Clark curated a one-day exhibition, Julian Dashper: Video Works, at the New Zealand Dominion Museum building. The location seemed fitting given the way Dashper engaged in artistic museology, conjuring the spectres of art history that haunt present practitioners, while concurrently folding himself into the canon. This aspect of his practice is perhaps best exemplified by The Big Bang Theory (1992–3), a suite of drum kits featuring the names of celebrated New Zealand artists emblazoned on the skins of the kick drums: “The Colin McCahons” et cetera. Ensuring their mythologies and collected works outlive their makers, Daspher re-presents them as both band and brand.

Now part of Massey University, the Dominion Museum building has, for me, always felt haunted by its complex and problematic past as a colonial institution incorporating both the Dominion Museum and the National Art Gallery. The building’s commanding location, perched on Mount Cook (named after Captain James Cook), is the origin point for the original survey marks made through the capital. I’ve always found the building an unlikely Pākehā cultural temple, embodied in an anachronistic European architectural form. Its monumental stone construction, huge columns and high ceilings, cold and murky corridors, and resonant acoustics are more than a little spooky. (Unsurprising, then, that it featured as a location in Peter Jackson’s supernatural thriller, The Frighteners.)

Dashper however, is a friendly ghost, and his video works felt at home in the old museum building, in conversation with its layered history and new identity. In Amery’s interview, Clark notes a further intention of the show:

To reflect on the current use of that building as an art school – so Dashper was … very involved in art education … came through art school, taught for a long time – and so it’s also trying to create these reverberations between pedagogical models of display, of art practice, of … artist statement, of the artist lecture, as a way to also … rethink art history in the space in which you can encounter it.

In the exhibition, Dashper’s The grey in Grey Lynn (1989) and Studio Songs (1998) were played on small, 1990s CRT televisions, placed on basic desks with power cables laid loosely across the floor in provisional set-ups, in keeping with their studio-based imagery. Untitled (O) (2003) was installed, as it has been before, on a similar TV, placed centre stage on the floor of an empty, dimly lit auditorium. In the work, a still image flashes for one second every fifteen: a photograph of Dashper’s painting Untitled (O) 1990–92 (1990–92) installed at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. The image flooded the room with light before promptly disappearing, plunging it back in to darkness. Within the empty theatre, the work felt like a flickering poltergeist, a ghost in the museological machine.

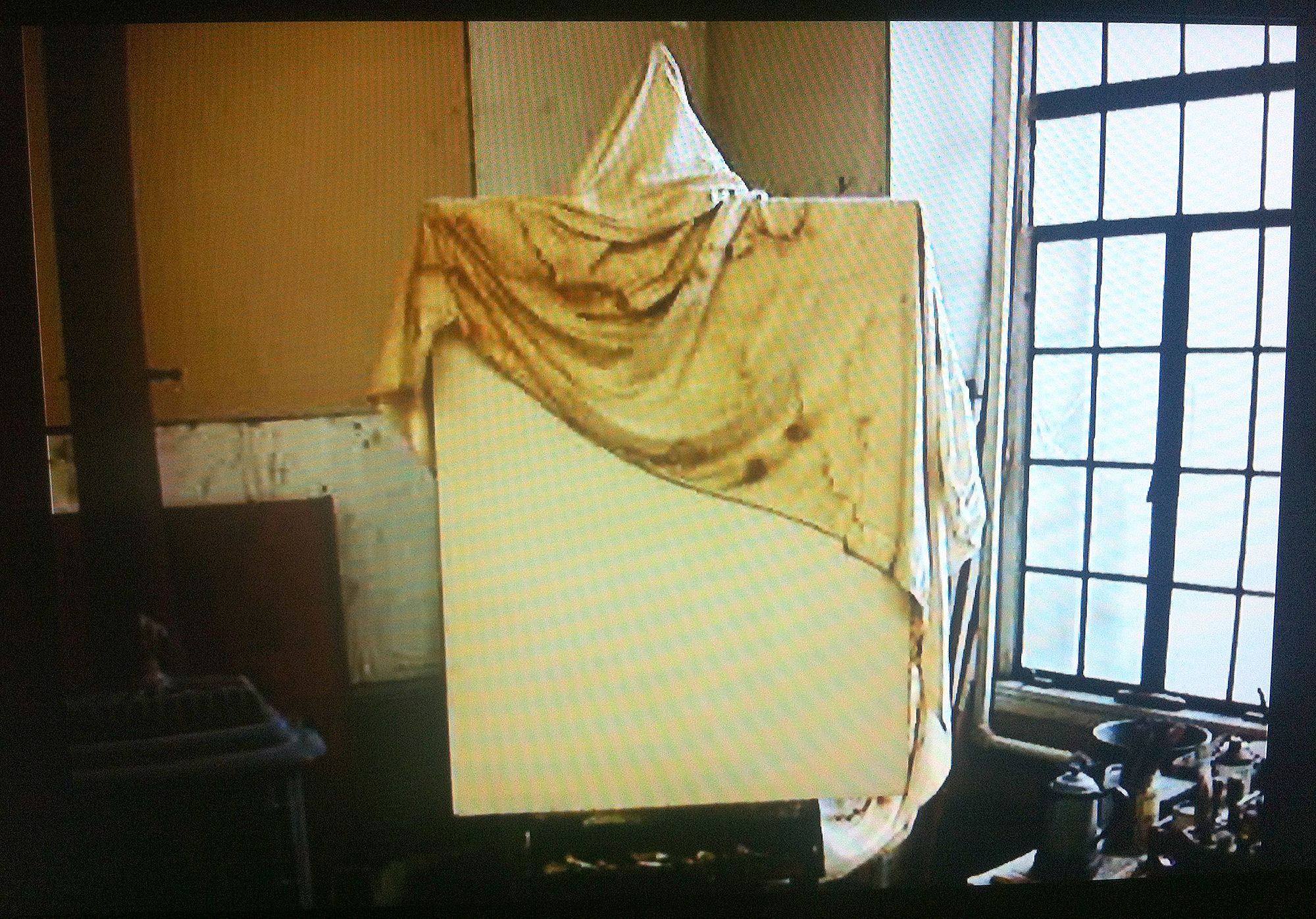

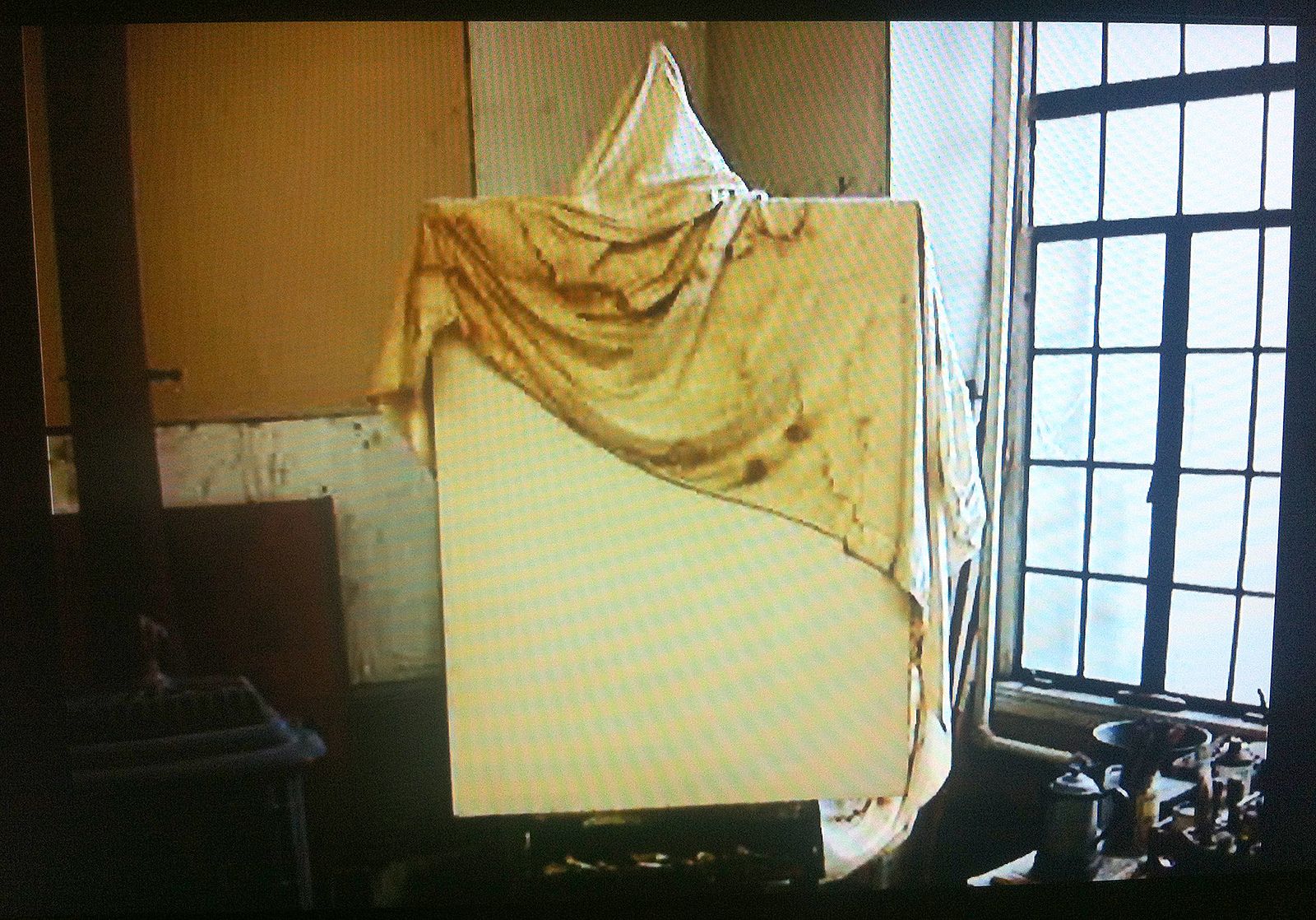

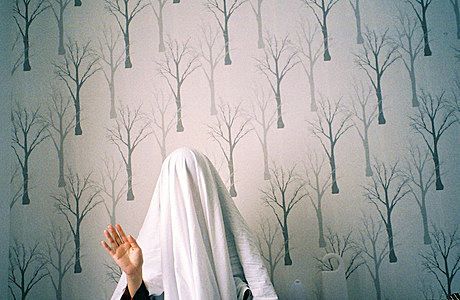

Untitled (after Thomas Hart Benton) (2006) – a low-resolution, early-generation digital video, nineteen seconds long and more like an elongated still – awkwardly jittered upon a new flat-panel monitor. The hand-held footage depicts a blank canvas on an easel in the studio of American painter Thomas Hart Benton, which Dashper had visited during a trip to the United States. The top of the easel and the canvas, prepared the day of Benton’s death, are partially draped in an old cloth. It appears Dashper noticed that the cloth’s placement was uncannily reminiscent of representations of ghosts. The screen was installed at head height, atop a contemporary unpainted metal display stand constructed of long vertical tubing, its form finding a parallel in the easel propping up Benton’s canvas. The doubling of surface and support cleverly reinforced the sense of absent presence conveyed by Dashper’s work.

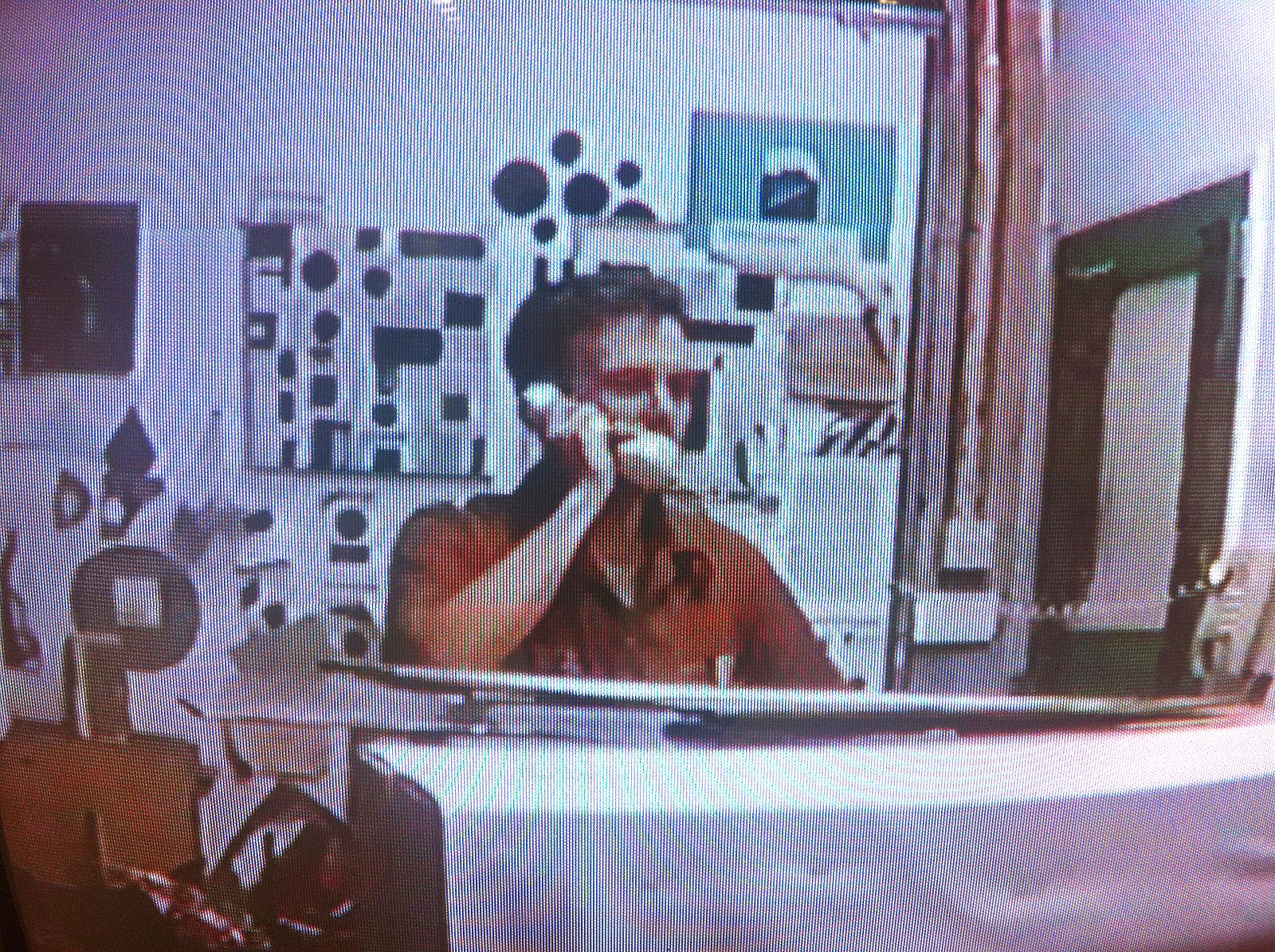

Unlike his work in other media, Dashper’s videos seem to speak directly to us from a space beyond. Though I have sometimes struggled to reconcile Julian’s warm character with the cool, hard edged, industrial appearance of his most abstract work, certain videos – particularly those he appears in himself – do bear witness to his unique and charismatic personality.

Exploring the exhibition, I walked past a room in which his partner, artist Marie Shannon, sat watching Untitled (this painting) (c. 2003). In the video, Dashper directly addresses the camera. The low camera angle frames him in front of one of his paintings describing its technical qualities to an undefined audience. He occasionally flits his eyes down the lens, connecting personally with the audience. When he first enters the frame from stage left, he glances at us and smiles. I left Julian and Marie alone in their shared moment together.

Earlier this year I had the pleasure of exhibiting alongside Shannon at the Dowse, in Alice Tappenden’s this is the cup of your heart. The group exhibition considered intimacy, memory, and loss in New Zealand art, presenting “intimate works that pay attention to the presence of absence in our lives”. Shannon showed a selection of text-based video works reflecting on her relationship with Dashper. A new work, The Rooms in the House (2016), centred on selected objects from her home and the memories of their son. Tappenden writes:

Julian is not here, but the things that surrounded him, that defined his presence, still are. For the moment they are meaningful, but what will happen in generations to come? As we are placed in the house with Marie, standing next to her as she rifles through memories, we are left to consider not only the things in her home, but also the things in our own. What will we remember?

Ever his own archivist and biographer, Dashper made it easier for us to remember him through the traces he left behind. In addition to these new, reflective gallery presentations, having Julian’s video work available on the CIRCUIT website allows audiences to continue to connect with his energy and presence. For those who knew him, it is also an opportunity to say hello again. Who knows, these digital files may one day outlive his material objects, floating freely in the electronic ether.

Though Julian now haunts a place in our imaginations, he is, perhaps, still right here. Maybe a ‘phantom topology’ is, at its most meaningful, a place within.