Wānanga kōrero: Our mana is inherent

How do we curate ourselves into existence? Mātauranga Māori Curator Matariki Williams sits down kanohi ki te kanohi with Faith Wilson, Hana Pera Aoake and Bridget Reweti to discuss Dark Objects.

How do we curate ourselves into existence? Mātauranga Māori Curator Matariki Williams sits down kanohi ki te kanohi with Faith Wilson, Hana Pera Aoake and Bridget Reweti to discuss Dark Objects.

Before I saw Dark Objectsat The Dowse Art Museum I knew that, prior to writing about it, I wanted to speak with the curator. The reason for this related to the structures that define the art world itself and my underlying concern about who would benefit most from a critique. The power of a critique is very real; it writes an exhibition into existence and holds that moment in perpetuity. Instead of the distant, one-way sense of a traditional critique, what was more important to me was to wānanga my thoughts with the exhibition’s curator, and current Blumhardt Curatorial Intern, Faith Wilson to get a fuller impression of her curatorial intentions.

The Blumhardt Curatorial Internship was established in a three way partnership between the Blumhardt Foundation, The Dowse and Creative New Zealand. Named after the ceramicist and arts educator Dr Doreen Blumhardt, the internship is one of the few paid art curatorial internships offered in Aotearoa New Zealand. Given the interests of the eponymous donor, the enduring thread of learning is a key focus of the tenure that is, learning from the institution about the collection and curatorial process involved in staging an exhibition.

With this in mind Faith and I had a long wānanga kōrero over pancakes with one of the artists featured in the exhibition, Hana Pera Aoake, and the 2014 Blumhardt Curatorial Intern, artist and curator Bridget Reweti.

The first question I had for Faith and Hana was prompted by a visit to the exhibition with a colleague where we both left feeling excluded by the works and label text. Given the content of the exhibition and the broad proclamation about portraying the diverse experiences and art practices of people of colour it was disappointing to feel that we, two wāhine Māori, weren’t the target audience.

“who is your audience?”

The opening wall label says that the exhibition “…resists old readings, and beckons you to engage with its complexities; to be with the tension, find new ways of seeing.” By imploring visitors to engage with the content in this way, I knew I wasn’t the target audience as those complexities to which the show alludes, are my own realities. They exist in my whānau, my work and the histories passed down to me.

Feeling excluded by the exhibition in and of itself is a frustrating feeling mainly because it is not a foreign one. The lens through which exhibition narratives are realised is determined by the curator, and with the majority of curatorial positions in New Zealand held by Pākehā, this results in a majority of Pākehā perspectives being told. Dark Objects features several self-identifying young women of colour who share similar experiences to mine and who I can speak in shorthand to about said experiences. Therefore, it feels a missed opportunity to not centre our collective experience and to privilege us as the primary audience.

So with this sense of exclusion I asked Faith, “who is your audience?”

It quickly became clear just how much institutional power structures weigh on her and Hana. Through the exhibition, Faith wanted to present the conceptualised lived experiences of women of colour for the benefit of the ‘traditional’ gallery visitor. By interpreting with the intent of teaching what she deemed a ‘conservative, white’ audience, the label text tended to explain concepts rather than discuss them, and in doing so they benefited that audience while presenting me with something I didn’t need.

I wonder why she would mould her experience to make it palatable to the very structures which oppress her.

Reading further between these lines I intimated that this conservative audience builds the foundation for the very structures that Faith and the artists feel oppressed by, a realisation that I struggle with and I wonder why she would mould her experience to make it palatable to the very structures which oppress her. This was an important point to wānanga together and Faith eventually stated that, with hindsight she might do some things differently. Which is not to say that what she’s doing now isn’t empowering her and I’d posit that while she’s curating to critique the power structures of the art world, she’s building the foundations of her own hegemony.

Within the sector I’ve had the great benefit of learning from, and reciprocally teaching upwards, some incredible tuakana. As a counterpoint to that inter-generational relationship, an art curator recently surmised to me that curators curate their peers and Dark Objects exemplifies that. The vernacular used and the movements in which the artists position themselves are ones that I can identify and access but are not necessarily ones that I position myself in. An example of this is the way in which they self-identify as ‘women of colour’, terminology that I would not use to refer to myself when I’m in Aotearoa.

Bridget and I have talked at length about the usage of this identifier in relation to rejecting the conflation of mana wāhine as Māori feminism and our belief that the latter cannot encompass the profound history of the former. Primarily I identify as Māori, being a wāhine is linked and empowered by being Māori but it is not definitive in the same way that being Māori is. Identifying in this way empowers me as it centres my whakapapa, the nuance of which cannot be matched by a collective term.

Online platforms were chosen by both Faith and Hana for the freedom they afforded to create their own spaces and link them to global conversations.

The way in which Faith and Hana use this terminology signified to me that they comfortably operate in an online environment in which this vernacular is the norm. Online platforms were chosen by both Faith and Hana for the freedom they afforded to create their own spaces and link them to global conversations. The negotiations of identity, which we also talked about from our own experiences, is apparent in the fluid ease with which they apply these terms. Further, the employment of these terms can be seen as a form of shorthand used amongst their peer group.

Given what the use of this terminology suggested for me, and its prevalence in their work, the question arose, “who do you talk to about your art and curatorial practice?”

Unsurprisingly, their answer was their peer group.

There is an inherent danger in creating within an echo chamber, we asked if they ever talked upwards, do they have tuakana, anyone more experienced to look to for support. Short answer was no, and with that came the admission that their peers would likely be unable to critique their practice as robustly as a tuakana would. Within this kōrero we spoke about the structure of the internship and the nature of discussing the research and curatorial framework with those who sit beyond the institution. When developing an exhibition, in particular one that speaks about cultural concepts which may be new to the gallery it will be shown in, there is a vital importance to talk with those who know, understand and live the kaupapa. Given the learning objective of the internship, it is apparent that this be a keen takeaway for The Dowse.

A robust critique does not necessarily mean that the questions asked are censorious, some questions can be gentle probes to get you thinking laterally about what you’re doing and why; provocations help to form a deeper understanding of your work. Key to a tuakana / teina relationship is that the dialogue, and consequently the learning, goes both ways, and it is within this exchange that the respect and trust, on which any successful relationship is based, is built between the participants.

…it was described as symbolising “power and sovereignty” a notion which I reject in favour of tino rangatiratanga and the privileging of Māori worldviews, worldviews that were trampled by an empire bearing crowns.

On a related note, one in which the past is acknowledged as the building blocks on which we work, I was intrigued by the inclusion of a crown in the exhibition, Hye Rim Lee’s Crown, Red. The first reason being that it was described as symbolising “power and sovereignty” a notion which I reject in favour of tino rangatiratanga and the privileging of Māori worldviews, worldviews that were trampled by an empire bearing crowns. The other reason why the crown caught my eye was because Bridget featured a pīngao crown by senior Māori artist Maureen Lander in her 2015 Blumhardt exhibition Nuku: Symbols of Mana.

Maureen’s work spoke to the Foreshore and Seabed Act, seen by many Māori as the insidious and ongoing creep of colonisation. I’d have loved to have seen a connection drawn between the two crown works somewhere, because again for me as a wāhine Māori visitor, the opportunity to hear from two women of colonised cultures about their interpretations of crowns is an opportunity not usually afforded to me. Again, without connections like this being drawn by outsiders, this peer group risks being too insular in scope which may cause them to become too focused on battles that will never love them back.

The revelation of which lead Bridget and I to question, “why do you want to be in the spaces that you critique?”

To put it quite simply, Hana said she was really angry. An anger that stems from creating within a sector that publically presents itself as bicultural yet to its very core is dominated by Pākehā artists, curators and directors. It’s an anger that I understand and feel; yet it can be blinding and prevent us from seeing that there are spaces in which we flourish and spaces in which our worldview is the norm. Front of mind in this respect is the consistent programming of Māori and Pacific artists at galleries like Pātaka Art + Museum and Taneatua Gallery as well as the way in which Kava Club expresses tino rangatiratanga by occupying space.

When we curate our worldviews as the norm, the space that is used up to explain our concepts is freed, making room for a stringent interrogation that will embolden our practice to evolve.

Bridget and I counter this anger, by asserting that as Māori and Pacific practitioners we have power in application, we can populate the places that strengthen us. When we curate our worldviews as the norm, the space that is used up to explain our concepts is freed, making room for a stringent interrogation that will embolden our practice to evolve.

At times in the exhibition the anger was deafening, and the ways in which it manifested bordered on prosaic. Someone recently told me, said in relation to working in a frustrating public sector role that deals with historic injustices to Māori, that there are ways of fighting these fights with aroha. This was an approach that had never occurred to me, why would I want to protect people who benefit from a structure that marginalises me? Yet, this is less about who you’re responding to and more about protecting yourself. Consistently working with personal trauma can be painful and demoralising, but turning that oppression into power by both ignoring it and knowing that your mana is inherent, puts you in control.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, it felt that addressing these hegemonic structures perpetuated their power as it took up the space that could be used to strengthen the inherent mana listed above. By focusing on the detail of the content, I felt that the cohesiveness of the exhibition was secondary when it could’ve have been used to temper the concepts.

Natasha Matila-Smith’s The Weight of the World, for example, is described as, “a gallery intervention that physically and conceptually challenges the institution.” The overt meaning of her work is apparent in its architecture as it is a fabric re-imagining of Roman columns intended to inculpate the dominant powers in place in galleries. An alternative placement for this work would have been at the entrance to the gallery, working with the layout of the space to elevate the physicality of the object, and to also use it as a barrier that reinforced the ensuing concepts explored by the other objects.

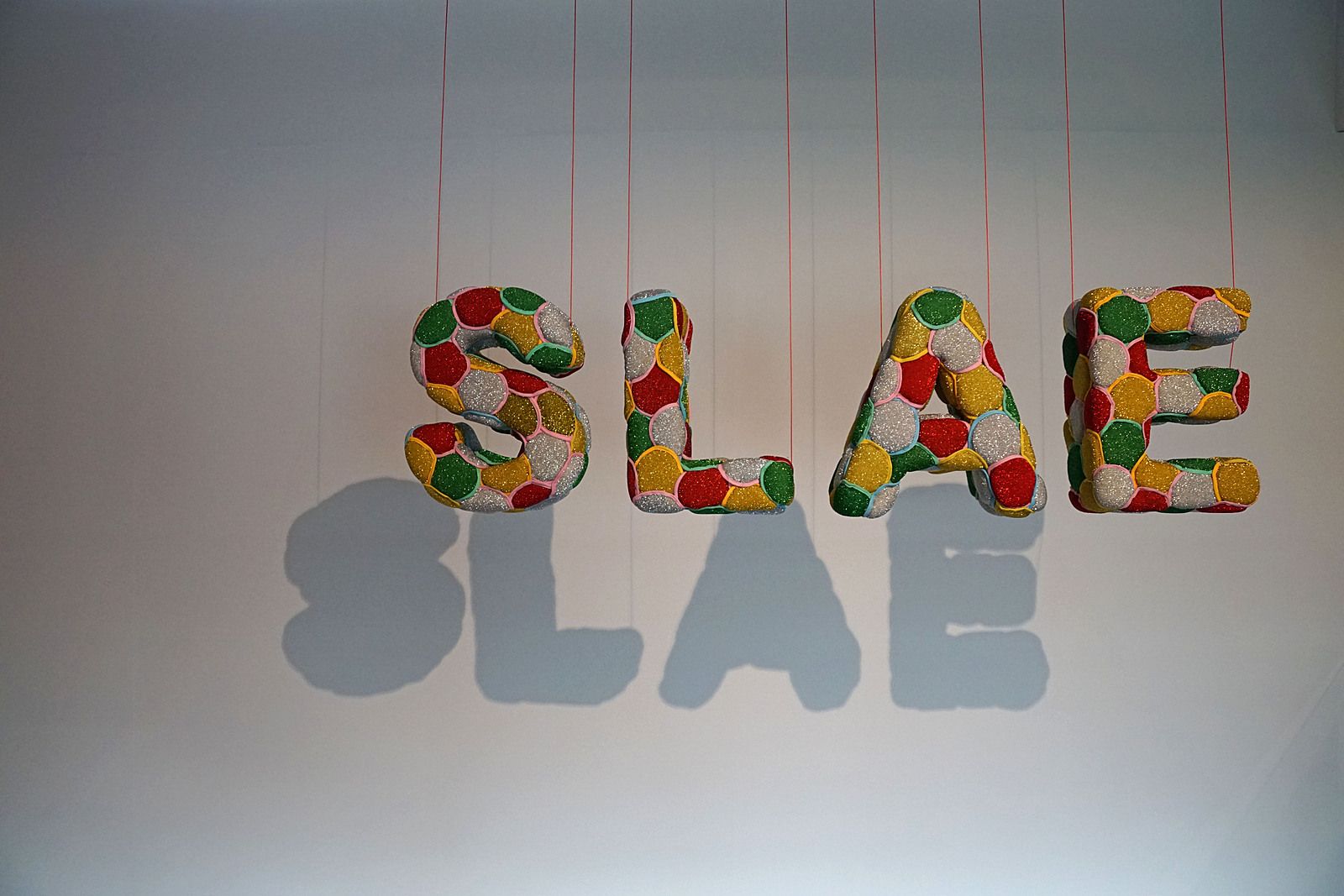

Given that another of the works played on the concept of physical space – Jade Townsend’s Plazzy Gangster – there was an opportunity for these two works to act in coalition and determine the navigation of that space. Plazzy Gangster references the Scouse slang of Jade’s mother’s homeland. Its allusion to identity coupled with its materiality gives it an interesting thematic link to Reuben Friend’s 2008 Blumhardt exhibition Plastic Māori that would’ve also been worth exploring.

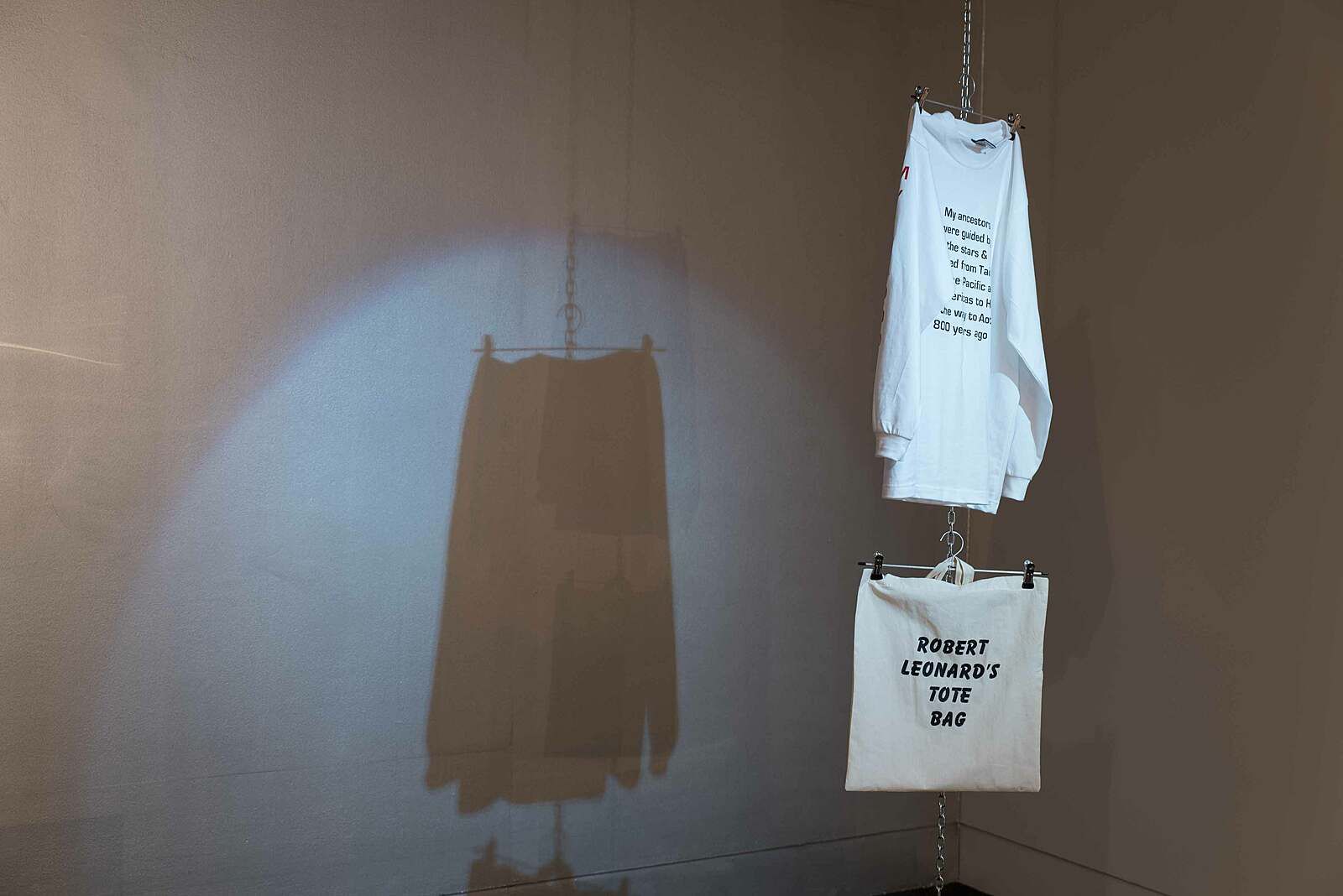

The textiles on display are made more powerful when worn, yet in Dark Objects they lack a sense of embodiment. For Clara Chon / Blue Blank’s Untitled painted leather jacket depicting Kim Kardashian, the label refers to the life it took on when worn by Kim K herself. Instead of working with the bodied nature of that activation, it hangs limply from a chain which again feels like a prosaic rather than nuanced display.

In Hana’s The Impostor Syndrome it is through the very wearing of the objects that the power was present and again the display lacks the integrity of its activated counterpart. One of Hana’s pieces is a tote bag emblazoned with ‘Robert Leonard’s Tote Bag’ in reference to the Chief Curator of Wellington’s City Gallery. This is another instance in the exhibition where I question why this peer group seeks recognition from someone that they feel excludes them. Since the unspoken dissolution of the Deane Gallery, the space in the City Gallery that was dedicated to exhibiting emerging Māori and Pacific artists, I’ve stopped putting energy into expecting it to be a responsive, progressive or interesting gallery for me. It was an empowering realisation and has meant that my time is spent in spaces that better represent me and want me there. This is not to say that these galleries should not be held to the same standard and that their programming needs to diversify.

The darkness which Faith states is immanent and which is present in her and the artists exhibited, can be likened to te kore: it is full of potential, it is the chaos just beyond our reach. It is in that potential that the power lies.

Before our wānanga kōrero and kai, I had never met Faith and Hana yet I had gleaned insights into their practice through previous exhibitions, their online presences and Dark Objects. Having to confront them with my misgivings about their practice in theory seems like an awkward prospect, unless of course the theory being applied is a kaupapa Māori one. Kanohi ki te kanohi, speaking face to face, is a central tenet of te ao Māori; at marae we raise our take publically and then we eat together. My understanding of the show, and what drives them, was made fuller by talking to them both. The darkness which Faith states is immanent and which is present in her and the artists exhibited, can be likened to te kore: it is full of potential, it is the chaos just beyond our reach. It is in that potential that the power lies.

Just like we need to write ourselves into existence, we need to curate ourselves into existence. The Blumhardt internship is all about learning, Faith and the artists exhibited know that we need to push these boundaries and challenge these structures. Most importantly, we need to talk up and down to one another and build our own mana. It is these kōrero that will take us forward, it is not the white gallery that will validate or define us. Our mana is inherent, and it is infallible.

In response to our wānanga korero Faith wrote this poem which she agreed to reproduce alongside this article:

brown girl magic

did u know that i’m magic

traipsing between worlds and galaxies

that others only dream of

cos i’m a smart brown girl

and i put my thang down flip it and reverse it

i was born with magic

but i lost it assimilating and dislocating and disconnecting

trying to dial up ancestors

tripping on acid

like all millennial clichés

clawing at the earth for answers

for knowledge that was beyond me

and all i had to look at was the cosmos

inside of me

my nana has all of the answers

locked up in her silver hair and fresh accent

i tried to become like her

and invoked the aitu

but the power was too dark for me

so i just plucked some of nana’s hair

silvery and full of light

and she said that i was born with a silver

streak in my hair

but it disappeared

but i’ve found the light and it’s growing

back but now it looks grey not silver

my magic is like a twista rap

fast and perfectly woven

and it will take you a while to understand

it is a glow in the dark yo yo

at a rave and you can’t keep up with it

it is a moonbow, glowing multicolour

rays and rare as hell

it is the voice of my mother

soft and harsh depending on the angle

my magic is brown like the earth

and the sand and my eyes and my skin

and it is mine and it shines

as big as the sun

Hana Pera Aoake, Clara Chon, Hye Rim Lee, Huni Mancini, Natasha Matila-Smith, Sorawit Songsataya, Jade Townsend

Curated by Faith Wilson

Dark Objects

The Dowse Art Museum

04 Mar 2017 to 23 July 2017

All images courtesy of the artists and The Dowse Art Museum.

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with The Dowse Art Museum, which covers the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.