A Frost Kissed Rose at the Bottom of the World: An Interview with Daegan Wells

Lucinda Bennett talks to the artist about craft, storytelling and finding his clay.

Lucinda Bennett talks to the artist about craft, storytelling and finding his clay.

My interview with artist Daegan Wells begins with a confession. I hold my phone up to the laptop camera to show him the lock-screen image of an overgrown red rose, its leggy stalk bending under the weight of a bloom larger than a teacup, gilded with frost. It’s a screenshot I took from Daegan’s Instagram story a few months earlier and he recognises it immediately, laughing delightedly – but my preternatural interest in roses means I have questions. This rose looks like an heirloom. Where in the world is Daegan that there are such old roses blooming under hard frosts? “I can see Stewart Island from my house,” he tells me. “It’s right at the bottom of the South Island. Super rural. We don’t have internet.”

Since early 2018, Daegan has been living on an isolated farm with his partner Scott – and twelve chickens, seven ducks, fourteen goats, a cat named Oliver and their new puppy, Gus. “The really wonderful thing about this place is that Scott’s family have lived on this farm for around four generations, and this is the original house. It’s so special, the garden is so established and beautiful. And then we have these crazy frosts that just freeze everything, and I love that. I love that rose.”

His work is perhaps best described as a kind of material storytelling where objects come to stand in for absent subjects, whether that be a person, a friendship, a place, even a story

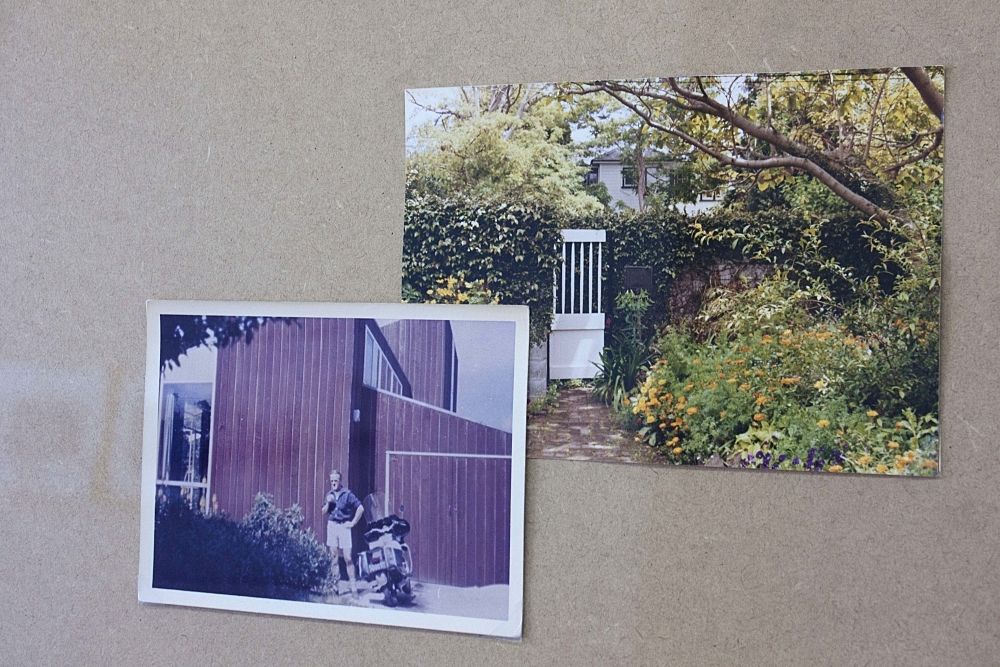

It feels right to begin with this image of a frost kissed rose at the bottom of the world. Or rather, it feels right to begin with this story about the image of a frost-kissed rose, for I realise now that it echoes another story told through a photograph of a garden – a photograph I was first introduced to as one half of Daegan’s work Bleached Terraces (2017), shown as part of The Tomorrow People at the Adam Art Gallery last year. During his first weeks in residence as the Olivia Spencer Bower Award recipient for 2017, Daegan spent time going through Spencer Bower’s archive at Christchurch Art Gallery (I should note that he refers to her rather cosily as Olivia, as though they are close friends). It was here that he came across a photograph of her home, the front garden oddly planted with springy alpine tussocks. The story goes that after mentioning to a friend – the potter Yvonne Rust – that she would love to grow these mountain plants in her city garden, Rust journeyed to Arthur’s Pass to dig some up for her, driving them back to Christchurch and planting them in her friend’s front yard. “It’s just such a good story, it made me wonder who is this lady? Who is this wonderful, wild person? At my pottery club last year, they were telling me how Yvonne used to fire her own ceramics in her garden. It was basically just a big bonfire and she would smother the whole neighbourhood in dark, black smoke and just wouldn’t care. She was such a badass. But she was also really interested in community and in teaching, so it’s really the stories, it’s her as a person. I see my grandmother in her. I just wanted to know more about her.”

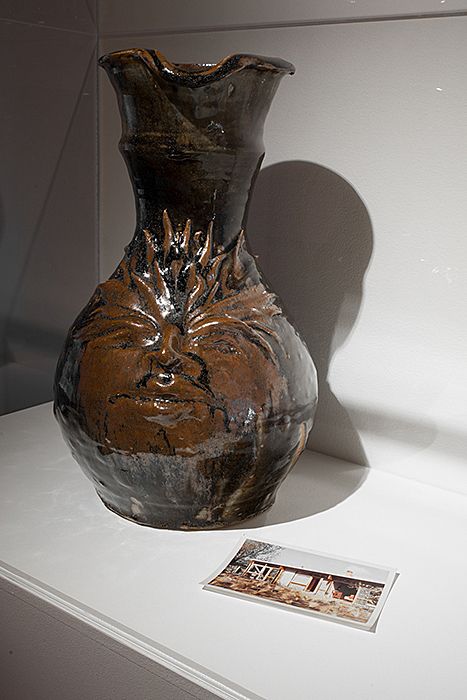

This nonchalant blend of stories feels an apt introduction to Daegan, whose work sprawls across all manner of media: photographs, ceramics, video, archival objects and loaned works by other artists. The second half of Bleached Terraces, for example, was a “bonkers” ceramic werewolf jug by Rust, loaned from Christchurch Art Gallery, shown on a shelf along with the photograph of Spencer Bower’s garden. His work is perhaps best described as a kind of material storytelling where objects come to stand in for absent subjects, whether that be a person, a friendship, a place, even a story. “I've always been interested in stories and storytelling,” Daegan tells me. “I'm dyslexic, and as a child was I terrified of reading but I loved books, so I would formulate my own stories by looking at the pictures…as a grown-up, I’m such a terrible storyteller. I know what’s involved in a good story but when it comes to a social situation where I’m telling a story, I’m awful. Using photographs and objects, I can tell a story with those, and I also love it because it’s so much more open.”

In his work, he has a tendency to romanticise his subjects – a tendency I imagine is hard to avoid when dealing with the potent contents of archives...

In person, Daegan is effusive and quick to laugh. Over email, he sends me a photograph of his "best country friend," a chicken named Grey Frizzle. In his work, he has a tendency to romanticise his subjects – a tendency I imagine is hard to avoid when dealing with the potent contents of archives, and a tendency that attracts me, a hopeless romantic, to his gently redolent work. Thinking about these qualities, about his love of archives and his recent move back to the rural place where he was born, I wonder if he considers himself a nostalgic person. “I guess I am. Or maybe I’m sentimental…I think a lot of my practice relies on language, on finding the right words to describe what it is that I’m really doing.” He goes on, “One thing I do worry about in my work is getting caught up in the sentimentality. I think I have this habit of making things whimsical – I just love living my life like that! But I do sometimes think it might be better to be a little less.”

This whimsicality is perhaps best exemplified in what Daegan refers to as the “Bill work” – a lengthy and fruitful research project centring on the garden of famed Canterbury painter William Sutton. I ask Daegan what drew him to the site of the Sutton house, and what held him there for so long? He responds with something of a saga.

I found the Sutton house by accident. It was late autumn and I was out in the red zone looking for walnuts. I saw a tree in the garden so I jumped the fence and immediately knew there was something special about this garden. It was wild and overgrown, the plants were mostly exotic species. I remember being fascinated by the tangled old fig vine at the front of the property. It wasn’t until much later, talking to my MFA supervisor Lara Strongman, that I realised I'd been on the Sutton property. At that time, I'd already been making work in the red zone for a number of months. I was living in the east of the central city, not far from the Avon River and the residential red zone. I would walk through the area to the supermarket a couple of times a week. The red zone was bizarre, with very few people and very little demolition at the start. It was normal to wander the abandoned streets and see no one at all – it was surprisingly peaceful, but also deeply upsetting. I eventually started to document what I saw; to photograph, video, and do sound recordings. I later began to go onto the properties and walk through the abandoned gardens. I was always surprised by what people had left behind – family photographs and other personal items. I began to think about the documentation as a sort of archiving – documenting these liminal spaces before they were totally lost.

Sutton had placed terracotta pots throughout his garden, some of which were purchased during a trip to Italy. After the earthquake, the majority of the pots were stolen or used to break windows to gain access to the house. It was because of this I felt an urgency to start cataloguing and documenting the site. I began by photographing the last remaining terracotta pots. I made a series of four silver gelatin photographs, documented on film and printed in the dark room. The photographs were later exhibited at Jonathan Smart Gallery as part of the group exhibition House Studies, curated by Sophie Bannan. Another work, Garden drawing (2016), was made on site from flower rubbings and berries applied to a canvas the same dimensions as the Sutton painting Private Lodgings (1954). The work acted as a stand-in for the garden and another extension of my documentation process. The Blue Oyster exhibition, Private Lodgings, was a coming together of all my research. The installation utilised a collection of Bill’s own photographs loaned to me by the Christchurch Art Gallery archive, which I showed alongside constructed forms, film, an original Sutton work and plant cuttings from the garden. The constructed forms reflected the heavy steel-and-wood gates that were stolen from the property, and they also acted as display panels for the photographs and the film. I assembled them from materials found in the gallery, and they were made to resemble makeshift barriers like those installed at Templar Street. I’d been interested in ‘transitional architecture’ for a while – ad-hoc forms used throughout Christchurch after the quakes. They were usually constructed from whatever materials were at hand, and in most cases used to prop or support things, or to keep people out of abandoned homes. This theme reoccurs throughout many of my previous projects.

Delving into the gallery archives of celebrated New Zealand artists has become a significant feature of Daegan’s practice, one that has caused reviewers to suggest his work is “fanboy” art, “obsessively heartfelt” and perhaps even a form of hero worship. Daegan himself doesn’t entirely shy away from these interpretations. “I am so interested in this idea of hero worship. I think it’s more just a way of me finding a place for myself as an artist.” He points out, however, that his work around the figures of Sutton, Spencer Bower and Rust has stemmed more from serendipitous encounters and findings than from an already present admiration. In the case of Sutton, for example, he tells me, “I knew of Sutton's work and appreciated it as any first-year art student would, but I don’t think I was a fan. It wasn’t until I found the garden and then visited the artist’s archive that I become interested in his work.” What is it about archives, then, that has seen them become so integral to so many of his projects? “I see so much value in them. For example, the photos [of Sutton’s garden] I showed at Blue Oyster, they’re so beautiful, and they were sitting in a box. And they really help talk about that specific site, so of course I used them.”

Daegan is remarkably gracious when it comes to discussing these critiques, pleased that people have taken the time to write about his work and raise such meaty concerns. When I venture my theory as to why these writers have focused on these aspects of his work – because it deals with archives and histories but is never overtly critical of them, and so is easily read as celebratory instead – he seems astonished. “I’d never thought of that, but you’re right! I think the work is kind of the meeting point of those two things. I don’t set out to criticise, and if I was then you would know about it, I would make that very clear. I think what the work is doing is really just being this point of observation. It’s saying look at this thing that I have found, this is what it is and this is what I think about it.”

This lack of position is perhaps frustrating to a viewer primed by so much contemporary art operating in the opposite way, art for which the declaring of politics is fundamental. “I think that’s so interesting, that having a position. It’s something I thought about a lot when making work around the residential red zone. It was clearly such a political place and I definitely had opinions and thoughts about what was happening there, but what I was really interested in was the people. I wanted to show the more personal – the middle ground of what was happening. I have opinions, but I don’t necessarily think they are the most or the only important thing for a work. I suppose it comes out of this idea of sharing a feeling.”

With Olivia and Yvonne…it was about working in a way they may have, taking on a way of thinking and researching

This notion of “sharing a feeling” crops up constantly throughout our conversations. Both of us keep circling back to it, employing it as a kind of shorthand for what is missing in the face of a necessarily disembodied exchange (given Daegan’s lack of internet connection, our interview took place via email and one lengthy FaceTime call made while he was housesitting in Lyttleton) – that is, the work itself, the physical encounter with these objects that have been chosen, made or grouped together in order to evoke a feeling, to gesture towards a story. Earlier in our conversation, he explained it like this: “It’s about carrying a feeling. With Olivia and Yvonne…it was about working in a way they may have, taking on a way of thinking and researching. I suppose for the Bill work, it was really about his garden, and his garden becomes representative of the issues that were happening in the city council, and the people who had to leave after the quakes.”

I am reminded of something Chloe Geoghegan wrote about Bleached Terraces in her review of The Tomorrow People; that “This kind of tributary practice is meaningful, but preliminary.” Daegan’s description of trying to take on Yvonne’s way of thinking and researching feels like a way of moving past this “preliminary” phase into new territory – something he seems to have achieved with his latest body of work, A Gathering Distrust, which included a series of ceramic vessels handmade using clay from the shore of Lake Manapouri. He tells me, “With the ceramic works I had at [Ilam’s] SoFA Gallery, Yvonne was there but not really. Only in the sense that I was interested in her research and the way in which she worked from the land with this really strong craft-based practice.”

...it’s not about making the best thing, it’s about that process of learning, of having a conversation with someone who knows what they’re doing

Up until this exhibition, Daegan’s work seemed more interested in considering craft practices, rather than making in the realm of craft himself. Does he have any desire to master a craft? “I often think about this, because when I’ve taken classes I’ve always wanted to be the best, so there’s a tension there. My grandmother was really important to me, she pretty much raised me, and she was always doing craft. She was always weaving or working with clay, she was such a craftswoman, always making something. I feel that is very present in the way I think about working with objects – it’s not about making the best thing, it’s about that process of learning, of having a conversation with someone who knows what they’re doing. I don’t think it’s necessarily about the thing that I make, it’s more about those conversations that take place, and learning a new skill…I think it is about these things representing a feeling, or a process, or a conversation, and all the steps you need to go through to get to that point.”

A Gathering Distrust marks a decisive shift in Daegan’s practice. The project has seen him looking towards his own history, considering the personal and political events that have shaped the world he now makes in, using a combination of video installation and ceramics to tease out issues and feelings around the Save Lake Manapouri protests. Begun in the 1970s, the protests were waged for 13 years before activists were successful in thwarting plans to raise the level of the lake in order to connect it with lake Te Anau to its north. Daegan’s own connection to the site is through a childhood spent there after his stepfather moved the family to Manapouri to take up a job as the above-ground superintendent on the hydroelectric power project.

His ceramic works evolved through a confluence of factors: through considering Yvonne’s processes of working from the land; in response to the political history of the Lake Manapouri site; and through unpacking his own memories and relationship to that place. “I was interested in this idea of having land that comes from one place, and having that be a stand-in. It’s such a literal thing, land taken from Manapouri, fired, now it’s here and it’s this; now it represents that space and that line. As a kid, I had a weird obsession with taking something from one place to another. I would take stones from a river and throw them in the ocean at the end of a car trip. Clay for me is this really literal thing, and I suppose digging clay from the site was really important.”

The resultant vessels are curiously formed. In her exhibition essay Elemental Forms, Sophie Bannan describes them as “vernacular vessels…like rubbings taken from the lake’s edge that narrate collective and individual stories; of returning to Manapouri with a spade; of falling through the clay seam on Frasers; of a fishing trip and a buried beer can time-capsule; of the movement that fought to protect the lake’s waterline.” I ask Daegan why they are shaped as they are, so roughly textured and urn-like. “Partly I was really interested in the ceramics of that time, around the 1970s when the protests were happening. But then the clay I was using was really unstable, so quite often the forms I made were because of the way in which the clay behaved. It collapsed really easily, you couldn’t work with it on a wheel…When it came out of the ground, it was basically this slime. It was full of water and was this really intense grey-green colour. I don’t know the physical properties of it, I guess it had some sort of mineral in it. It was beautiful though. It was awful to use. That’s the thing about using clay you find yourself, it’s really unpredictable and there’s no instructions on how to fire it.”

Yvonne Rust had a lot to say about potters mining their own clay. Perhaps most resonant with Daegan’s work is her instruction to “...first find your clay.” In Elemental Forms, Bannan suggests that Daegan found his clay when he fell “through a torn seam of clay on Lake Manapouri’s Frasers Beach as a kid” – although he only recognised it as his when he returned to excavate it in 2017.

I can’t help but draw poetic (romantic?) parallels between this and Daegan’s childhood obsession with moving things from one place to another. And then there is his recent move – or rather, his return – to Southland, to a farm right down the road from where he was born and lived until the age of about five. When I suggest that perhaps he is unwittingly applying his research practices to his own life now, returning, as it were, to his own archive, Daegan thinks perhaps this is true. “Being there just really makes sense. There’s this sense of trace, the remnants of something…I’m seeing traces of my childhood, traces of my grandmother and my mum in the architecture and the buildings, the roads, it’s all there. I think my practice has always existed parallel to my life. I’m always responding to the things around me. Being here, that’s exactly what I’m doing, I’m responding to this site. Even if I were in Auckland I’d be doing the same thing. There’s just no way I would have thought I’d find myself back here.”

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with Blumhardt Foundation. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.