Digital and Analogue: Impressions of Cortright and McCahon

Leo Thomas looks at two artists with very different approaches to painting.

I woke at 9am to the sound of my alarm, did my best to retain consciousness, made some coffee, and drove my dusty, hubcapless station wagon downtown. It was opening day for four new exhibitions at City Gallery Wellington, including On Going Out with the Tide, a collection of work by renowned New Zealand painter Colin McCahon, and RUNNING NEO-GEO GAMES UNDER MAME, an exhibition of digital works by contemporary American artist Petra Cortright.

Aside from occasionally encountering McCahon’s work at Te Papa I hadn’t seen much of it since studying him at high school. I was eager to delve deeper into his painting. The only work I’d seen of Cortright’s was online. This seemed appropriate given the artist’s preoccupation with the digital, one hinted at by the name of her exhibition, which alludes to running old-school ‘Neo Geo’ arcade games like Metal Slug, Bomberman, and Puzzle Bobble on a MAME (Multiple Arcade Machine Emulator) – a reference too nerdy even for me to get on first reading.

Approaching the gallery, I felt the sense of excitement and vague apprehension I usually experience before visiting a gallery – unsure what to expect, compelled by the unknown, while simultaneously feeling that I might somehow seem out of place. I took comfort knowing I could escape into my notebook intermittently to record my impressions. After being greeted by the friendly staff, I began with a cursory examination of the work on display, imagining myself a sort of flâneur, walking leisurely but without hesitation though the exhibits to gain an overview. On the ground floor: three rooms with works by McCahon, mostly monochromatic, centring on Māori text and themes.

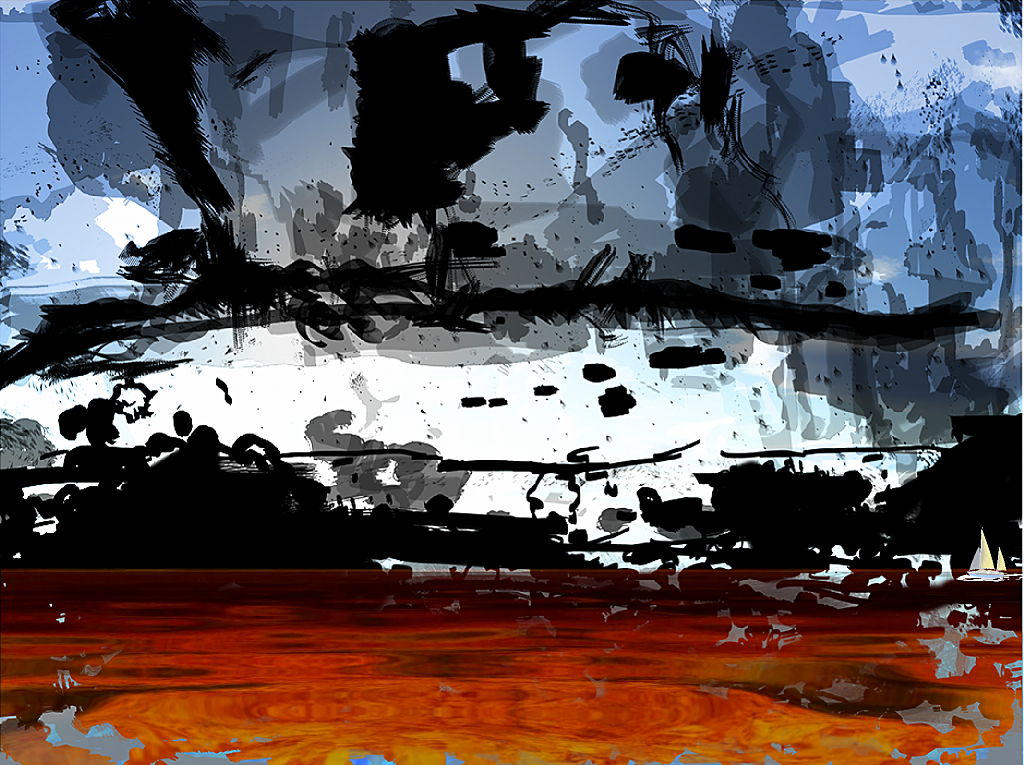

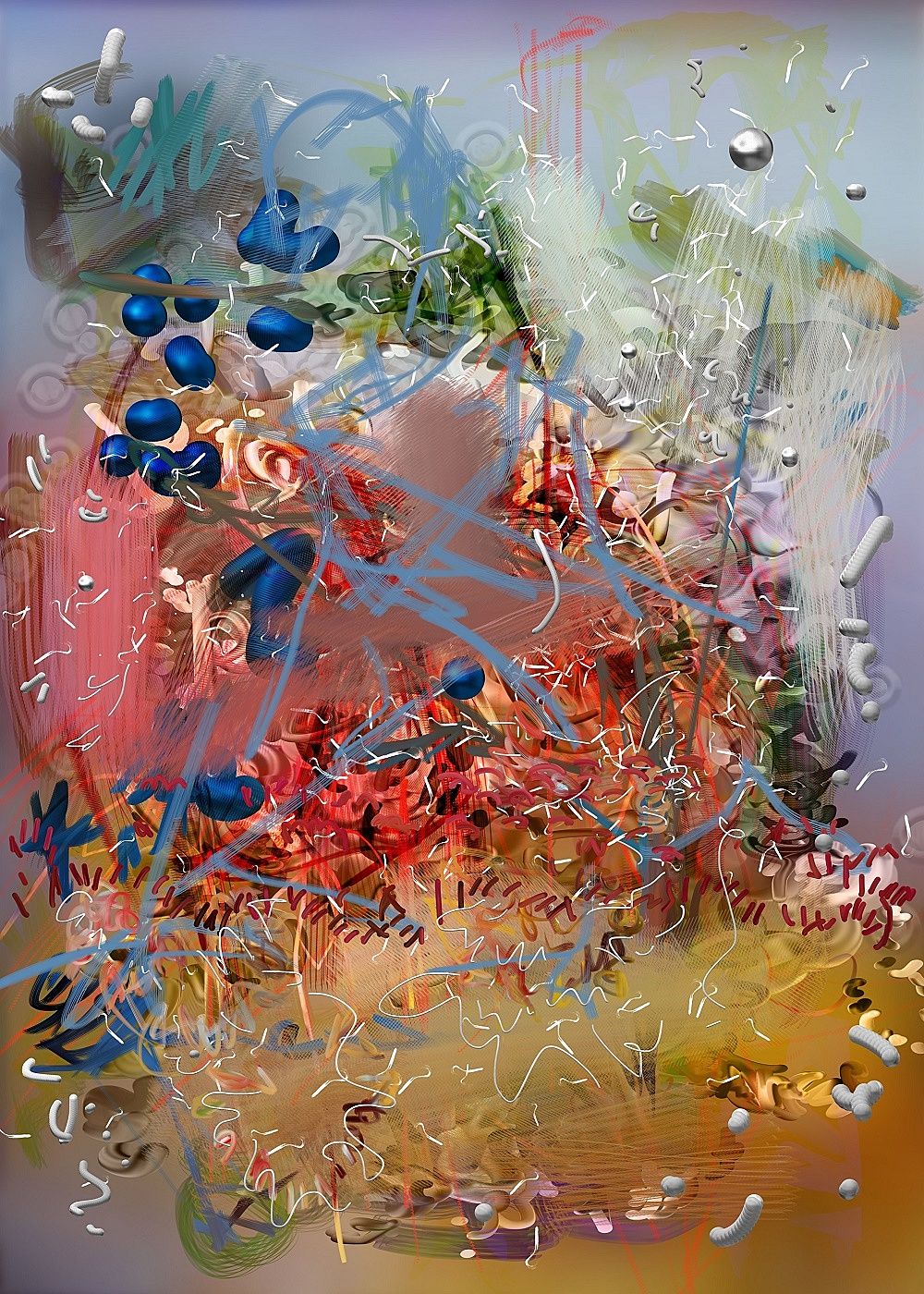

Cortright’s works were upstairs. In one room was a series of her digital paintings printed on linen and paper – abstractions with multi-layered swirls of colour. The next space over contained several of her video paintings – impressionistic landscapes with kitschy animated elements and atmospheric sound effects like running water and chirping birds – and webcam works showing Cortright herself. A third, darkened room with a full wall projection of another video painting by Cortright offered respite from the crowd. This work, Clouds Over the Ocean_with_dark_painting (2016), was overtly digital, with low resolution seagulls flying through a digital-artefacts-laden sky, as a pixelated dolphin and sail boat made their way across a lava orange horizon.

I sat in one of the bean bag chairs to collect my thoughts, my first impressions of the vivid contrast between Cortright and McCahon, their works almost antithetical – McCahon’s sombre, monochromatic, austere; Cortright’s bright, multi-coloured, playful. I checked my phone and found it was nearing 11am. I made my way back downstairs for a tour of On Going Out with the Tide.

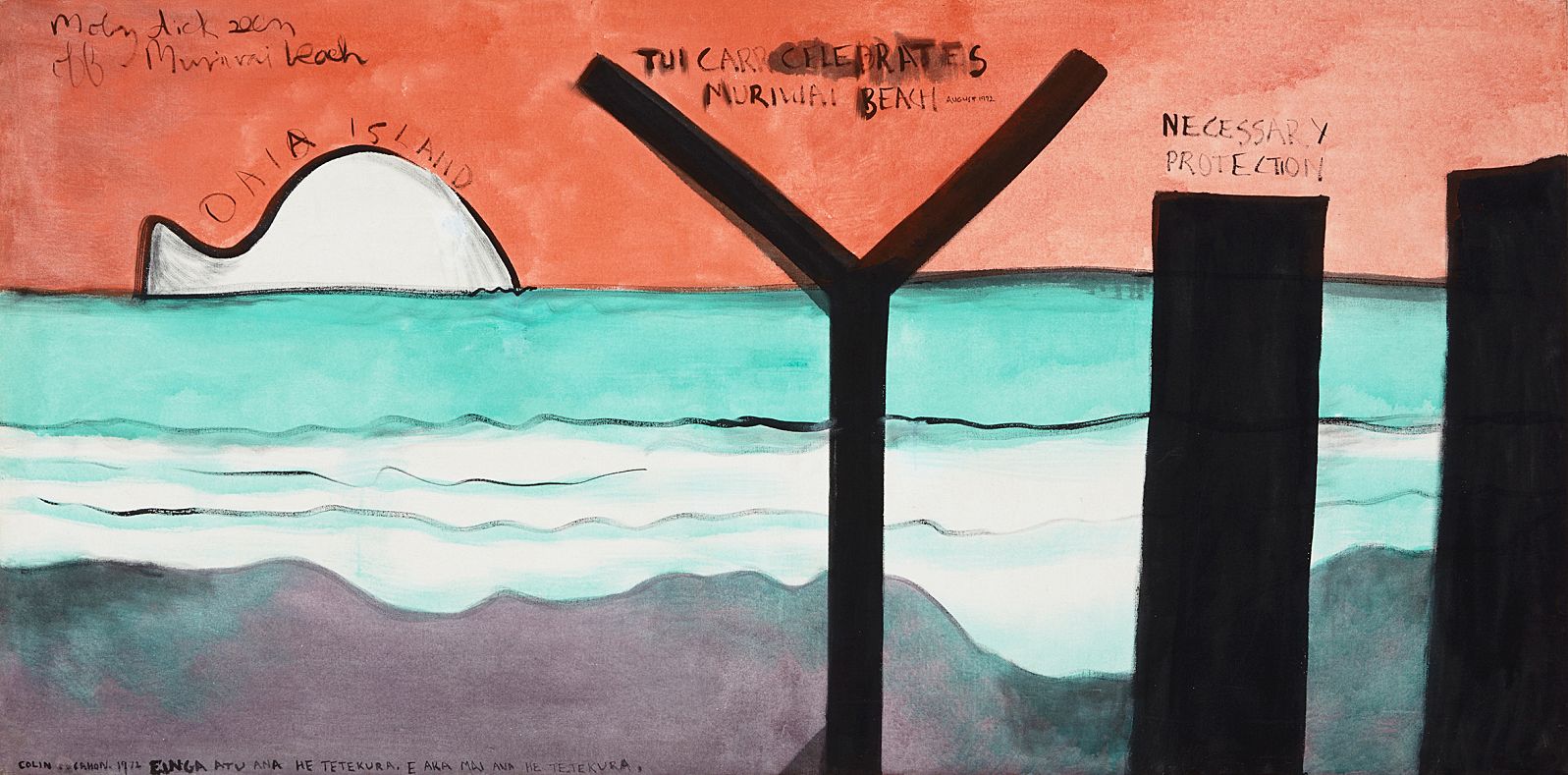

The curators, Wystan Curnow and Robert Leonard, spoke of McCahon’s Māori grandson and how his birth had spurred the artist’s interest in Māori language and culture at a time when it was mostly overlooked by Pākehā in the arts. The works on display included The Canoe Tainui (1969), which recently became the most expensive painting to sell at auction in New Zealand. Purchased for a mere $550 during McCahon’s lifetime, it recently sold for a staggering $1.35 million – quite the argument for investing in living artists. The work itself presents the whakapapa, or genealogy, of the grandson, detailing the names of his Māori ancestors.

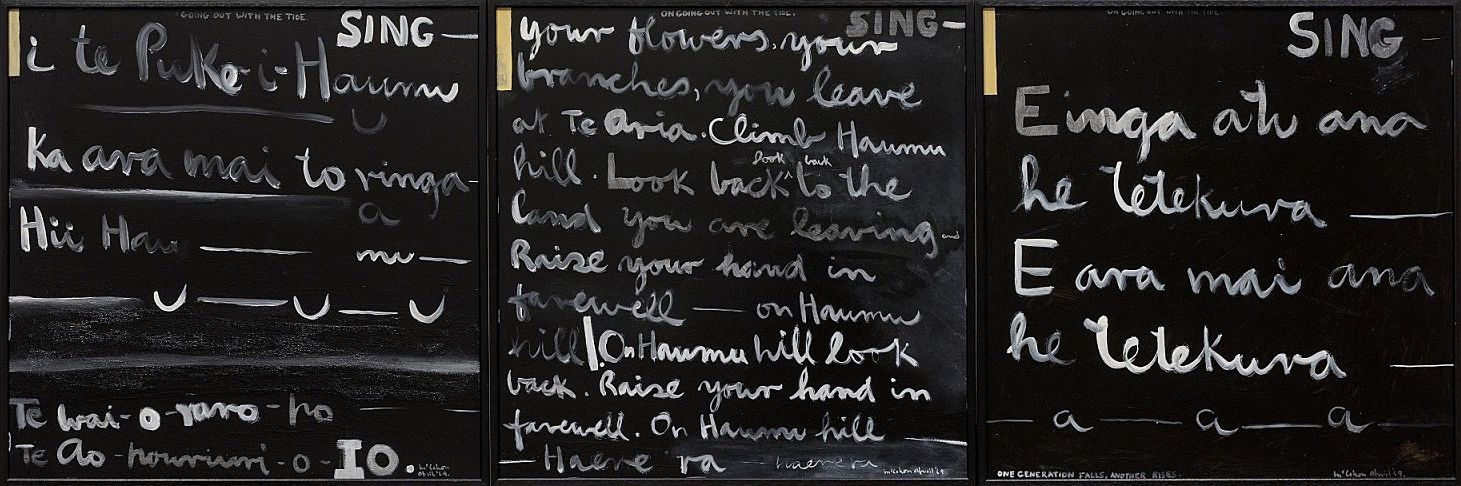

The eponymous On Going Out with the Tide (1969) is similar in style, including Māori excerpts from a text of the same name by Matire Kereama, an elder whose work inspired McCahon and who provided the whakapapa for The Canoe Tainui. The title refers to Māori beliefs in the afterlife, as articulated by Kereama in her text: “When I was a child no person died without first asking about the state of the tide, whether it was full or low. People always liked to die at low tide because the tide had to be completely out to reach Te Rerenga Wairua, ‘The Leaping Place of the Spirits’.”

McCahon’s use of Māori culture can be seen to raise larger questions of cultural appropriation which City Gallery Wellington has chosen to frame in terms of “emerging biculturalism”. My impressions, considering McCahon’s familial affiliations and friendships with Māori artists and writers, is that his treatment of Māori culture is reverential rather than affected, but such matters are up for debate. The fact that some of New Zealand’s best known art works addressing Māori themes were created by a white guy is far from unproblematic.

Leaving the McCahon show, I returned to the first floor to listen to Cortright and curator Aaron Lister discuss her work. When it was observed that the artist has been called the “Monet of the 21st century”, I couldn’t help but wince, not because I don’t appreciate her work, but because a compliment of that magnitude – a direct comparison to one of the greatest painters that has ever lived – can only seem disproportionate in reference to a contemporary artist. (One of her videos did feature some copy and pasted water lilies, but whether this merits a comparison to the founder of Impressionism is certainly a matter of contention.)

Cortright explained her process, her preference for Photoshop, Wacom tablets, and styluses over canvas, paint, and brushes. She spoke about her internet-sourced imagery and the digital brushes she creates and downloads. Interestingly, when asked about her influences, she referred simply to “classical painters” – despite her preference for digital over analogue, abstraction over representation, and having called painting “the slowest, dumbest thing on the planet”.

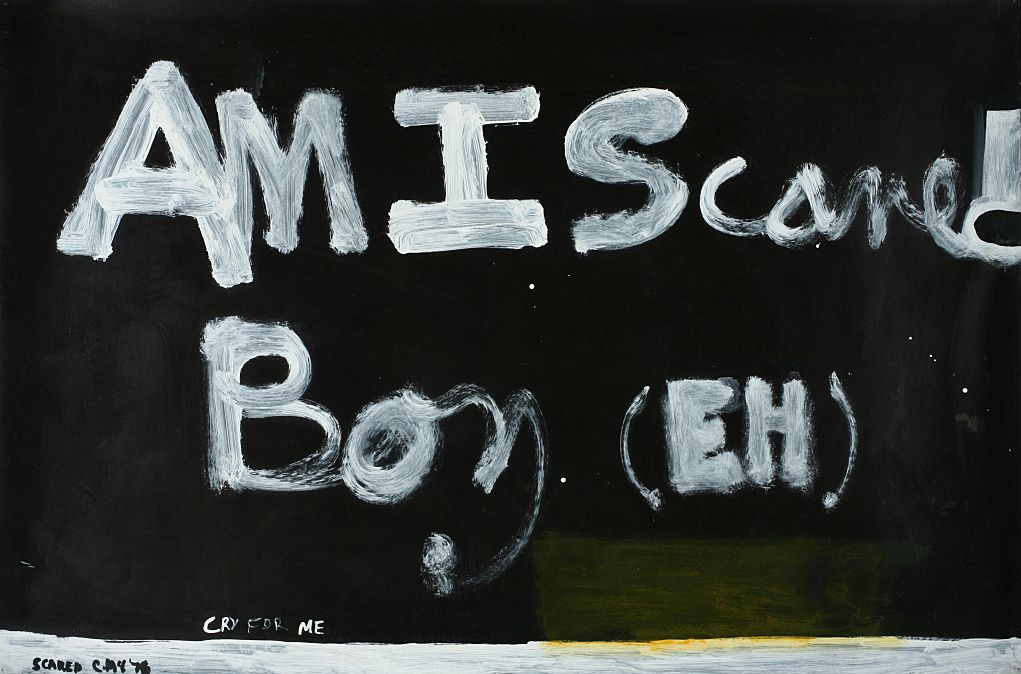

The Gallery was pretty crowded by this stage, so I decided to grab a bite to eat. I returned to the gallery that afternoon and several times over the following days. I became quite fond of McCahon’s more minimal paintings, like Io (1965), which conjures associations with the Māori god of that name, but also with Io of Greek mythology, condemned to restlessly wander the earth. The void of black, strongly reminiscent of a headstone, reminding the viewer of the inescapability of death.

Sometimes I found I preferred the titles of McCahon’s works to the paintings themselves. I was particularly taken with The Days and Nights in the Wilderness Showing the Constant Flow of Light Passing into a Dark Landscape (1971). The titles of Cortright’s works, on the other hand, evoked more wry amusement than aesthetic satisfaction. The title of her video painting 007goldeneye.sexual_videoconferencing_characterscheatsharks.edu (2016) is so disparately contrived that I laughed out loud when I first read it. The work itself was seemingly unrelated to anything mentioned in the title. (The same is true of the exhibition title. None of the works overtly refer to Neo Geo games or to emulators. Nor do the curatorial notes elucidate any significant connection.) Still, I found the work and its slowly morphing gestural colour fields pleasing.

With each visit, I noticed further contrasts between the works of the two artists: Cortright’s conveying a sense of movement, sometimes literally in motion; McCahon’s relentlessly static and monolithic. Cortright’s almost synesthetic and, in the case of her video work, actually auditory; McCahon’s silent, brooding, unyielding. The digital nature of Cortright’s work highlighted the physicality of McCahon’s. He would sometimes mix sawdust with his paint to add texture to his works, an effect impossible to replicate with pixels alone.

McCahon’s work is often culturally and philosophically significant, including references to religion, death, and mythology. Cortright’s often feels whimsical, frivolous. A two-time art school drop-out and self-confessed “horrible student”, she does not wish to overburden her work with too much thinking: “The work is better the less self-aware it is. I try to be a self-aware person, but I don’t want that in my work.”

But Cortright and McCahon also share similarities. They both embrace the abstract tradition whole-heartedly. Both show the influence of American abstract expressionism – McCahon’s work often calling to mind the colour field paintings of Mark Rothko, whose work he viewed during a trip to the states in the 1950s; Cortright perhaps more evocative of the gestural work of Willem de Kooning.

I had difficulty finding anything of interest in Cortright’s webcam works, which suggest Andy Warhol’s videos featuring static shots of celebrities and the artist performing everyday tasks like eating a hamburger. They’re poorly made – the crackly low-fidelity audio more abrasive than experimental – and don’t seem to convey any deeper meaning. Considering how inundated we are with digital content, with three hundred hours of video uploaded to YouTube every minute (and this number only continuing to rise), I question the value of someone standing around messing with webcam filters. Mundanity gets old fast.

Oddly, Cortright seems to agree with this sentiment. In a recent interview she noted, “They’re not nice, long, highres videos. They’re shitty, really weird, webcam videos. I’m constantly so grateful that people want to buy my work.” The videos’ limited views on YouTube seem to confirm that their significance is derived primarily from their acceptance within the artistic community, rather than any intrinsic interest value of their own. Although one could say something about the distinction between art and entertainment, or point out that some of her works have been removed from YouTube due to her use of offensive keywords, you’d expect videos worth watching for their own sake to have more than a few thousand views, especially after significant promotion and contextualisation as “art objects” in galleries.

There is much about Cortright’s work that I do appreciate. Her video paintings reinterpret the classical tradition in interesting ways, updating it with sound and motion for the present moment. The notion that we need not be confined by the static image in fine art is a compelling one. Given Cortright’s aversion to the academic, the deeper implications of her work are perhaps best articulated by Lister: “A lot of people will say this isn’t a painting. But is painting an idea, or a material? It makes you rethink what defines painting, what defines art and how a digital existence can shift those terms, which is so relevant.”

Still, in an increasingly digital world in which artists like Cortright are selling jpegs at gallery shows, I think there is something increasingly appealing about tangible artefacts. Then again, as fixated on the digital as she is, Cortright continues to produce prints of her works, so we can no doubt rest assured that the art object isn’t going anywhere. Ultimately, I’m grateful for the contribution of both of McCahon and Cortright to the ongoing aesthetic dialogue, and for their demonstration of the myriad ways in which creativity can be instantiated. As for whether Cortright is the Monet of the 21st century, this is probably a question best left to art historians of the future to answer. Personally, I wouldn’t bet on it.

All images courtesy of the artist, City Gallery Wellington, and Tristian Koenig.