Attuning to People, Places and Things: Neck Adornment and Contemporary Art

Victoria Wynne-Jones ruminates on the fruitful intertwinings of neck adornment and contemporary art through the practices of Sione Monū, Renee Bevan and Lisa Walker.

Victoria Wynne-Jones ruminates on the fruitful intertwinings of neck adornment and contemporary art.

A necklace is a slight weight that sits on the skin at the top of my chest. Whenever I put one on in the morning, I dip my head forward as if to bow, eyes lowered. I concentrate very hard so that I can open and close the unseen clasp. Or, I lift it up and over, ducking my head into its circular form before adjusting it with a thumb and forefinger so that the pendant sits on the centre of my chest. Meditating upon what it means to wear a necklace, I remember a passage in which the late John Berger wrote about our monkey-ancestors who, once they began using their arms, began to become brachiators.1 Berger points out that it is thanks to the way in which the brachiators hung from trees “that we have long collarbones which keep our arms away from our chests.” Therefore it is thanks to many prior acts of hanging from trees that we have a space to wear adornment at our necks.

There is a play with purpose and utility as well as a joyful exploration of hanging, looping and encircling forms and shapes.

The following is an account that delights in the current moment in which neck adornment seems to be insinuating and intertwining itself within contemporary art. Aotearoa-based artists from different generations have been probing the ways in which adornment might be worn around necks. Artists Sione Monū, Renee Bevan and Lisa Walker each inflect the necklace in various ways, reimagining it in turn as a kahoa or garland, a string of beads upon the ground, or a bundle of material hanging from a hook. Each instance realises a unique approach to the form as well as particular ideas about embodiment, identity, intimacy, mortality and materiality. There is a play with purpose and utility as well as a joyful exploration of hanging, looping and encircling forms and shapes.

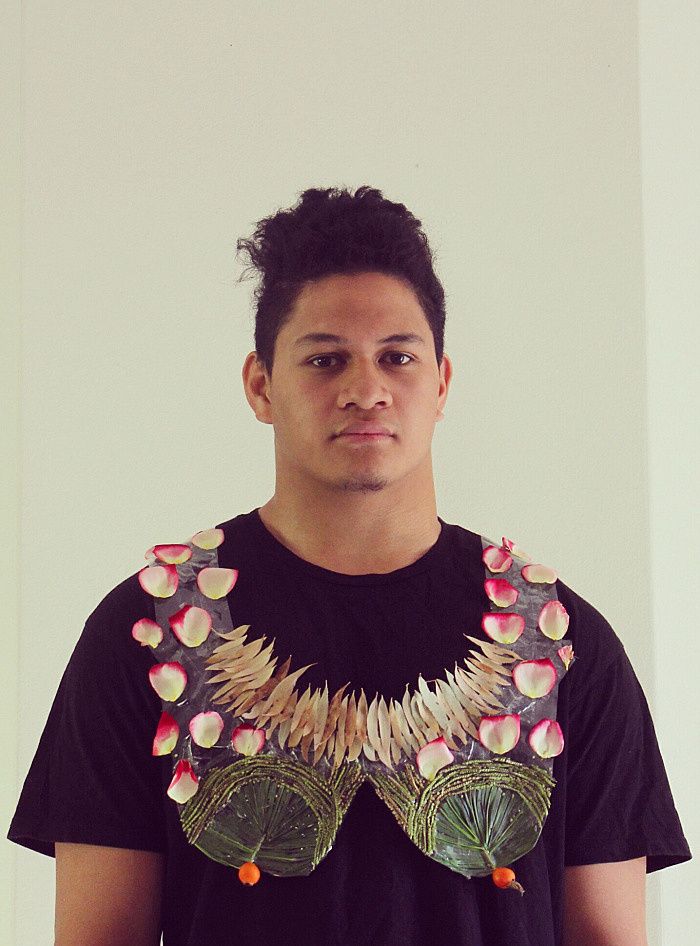

Composed of seed pods, twigs and pale purple petals, this particular instance of neck adornment was made and photographed by Sione Monū and is worn here by his friend and fellow artist, Jermaine Dean. It was in fact made especially for Jermaine, from materials found around the location in which he is photographed, whilst he and the artist were spending time together. The large-scale digital print shows Dean, mid-exhalation, smoking a cigarette, sitting cross-legged on a porch sporting Monū’s newly created piece. Perfectly composed, he is framed by the horizontals of the weatherboard walls and the grid-like forms of the windows. Beside him, on a table, can be seen the plants from which some of the elements of the piece have been taken. Jermaine Dean (2017) is one of a series of 16 digital prints that made up Monū’s first solo exhibition, Kahoa Kakala. Developed by the artist as part of a collaboration based on mentorship with curator Elle Loui August, the show took place at Fresh Gallery Ōtara and then at Objectspace, Ponsonby in the spring of 2017. Developed over a period of 24 months, the curatorial process involved supporting Monū to develop an exhibition framework, to learn new processes and to connect the artist with practitioners from the Tongan community. Creating a space for shared making, storytelling, performance, collaboration, mentorship and the exchange of knowledge, as well as support from a broader community was integral to the project as a whole.

Ephemeral, each of Monū’s garlands is crafted from organic matter, sometimes with an adhesive plastic backing, sometimes including techniques of weaving, plaiting and knotting learnt in Tonga. The adornment worn by Dean was inspired by a Tongan fan shown to the artist by curator Kolokesa U. Māhina-Tuai and community engagement facilitator Barbara Makauti-Afitu at the Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira. It shares the fan’s rounded three-sided form and its use of negative space, but replaces its multi-coloured fringing with flower petals. Monū’s piece is an intricate play between a slender framework of twigs making up a collection of angular, pentagonal units in which dried seed-pods are suspended, and a frill of zig-zagging purple petals. The exquisite, delicate piece has then been placed upon Monū’s friend’s chest in an act of honouring, and then captured as an image whilst the petals are still fresh and the twigs still taut.

Formerly based in Canberra, Australia, Monū relocated to Māngere after having been inspired by Pacific artists currently practising in Tāmaki Makaurau. He was particularly tempted by the prospect of participation within socially active and creatively motivated collectives such as FAFSWAG and Witch Bitch. A maverick working across multiple forms of media, Monū’s artistic practice spans instantly accessible self-imaging for online platforms as well as adornment, drawing, design, photography, film-making and performance. Recently, works by Monū have been included in group exhibitions around Tāmaki Makaurau curated by Tanu Gago, Ema Tavola and Louisa Afoa. Following on from his series of Instagram self-portraits wearing blankets customised to look like decadent evening gowns or robes, Afoa’s iteration of SOCIAL MATTER at RM Gallery on Samoa House Lane (just off Karangahape Road) included a #BlanketCouture Portrait Day in which participants could be photographed by Dean, once regally styled by Monū in kafu or blankets. This pattern of adorning and photographing others can be seen throughout Monū’s practice. An earlier body of work, Canberra Family Portraits, involved photographs of Monū’s family in his house, each wearing adornment of his own making. The portraits were made following the artist’s research into lei and the ways in which they are made to be gifted, as part of dancers’ costumes, often as signs of respect and as part of celebrations.2 Monū proceeded to improvise with the form, crafting his own instances of adornment for each of his family members using a range of adhesive materials and plants from his backyard. These concerns are extended in Kahoa Kakala, in which Monū continued his research and experimentation with nimamea’a tuikakala or Tongan flower design, in particular the kahoa or garland.3

...“the most precious pendant in the world would be a string of arms and the body of your loved one hanging like a pendant around your neck”

Like each of the images in Kahoa Kakala, Jermaine Dean acknowledges an encounter between artist and sitter. The photograph marks a particular place at a particular period of time, but more importantly it commemorates time spent making and time spent together with friends and extended family. Each of the sixteen prints is a portrait of someone close to Monū wearing adornment he has made from plants sourced mainly from their backyards. Thus each portrait enacts invisible connections, enfolding within it complex contexts and relations. There are familial ties, friendships, histories, stories and alliances. There is love. Materially, the garlands and adornment are testament to the specificities of suburbs and idiosyncratic backyard ecologies, whether they include carefully planted flowers, shrubs introduced by previous tenants or those normally categorised as weeds. The vegetation that is incorporated into Monū’s neck adornment has been shaped by particularities of past seasons, periods of growth, rainfall and drought, making the pieces evocative and ambient.

Just as Monū demonstrates his reverence for his friends and family through bedecking them with garlands or artfully draping them with blankets, Renee Bevan has draped herself around the necks of those close to her as an act of honouring and love. In Renee Bevan Necklace (2012, 2014, 2015) a live performance with participants is documented through a series of photographs. Stripping the necklace right down to its core, its physical configuration as well as the way that it might function emotionally, the first performance involved Bevan as a human necklace being worn by her husband. Subsequent iterations involved family members, friends and strangers all photographed wearing Renee Bevan pendants. Rather than a pendant or necklace acting as a reminder of someone, a surrogate or stand-in, it becomes the jeweller herself. Bevan, like Monū, sees neck adornment as a device that connects people together, so that “the most precious pendant in the world would be a string of arms and the body of your loved one hanging like a pendant around your neck.”

Burial Necklace is a reminder of what is at stake with jewellery: frequently, it is a matter of life and death

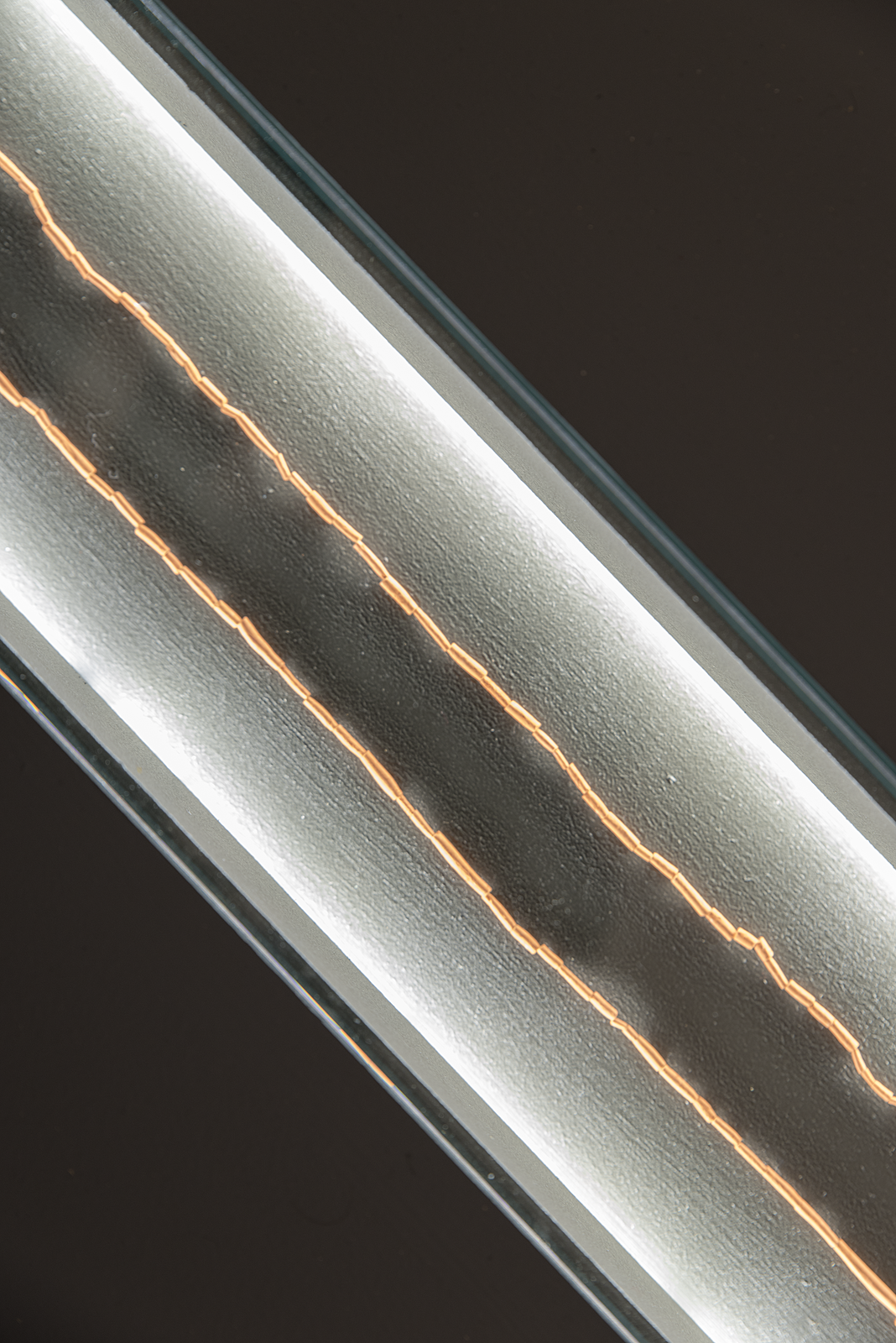

Similarly human in scale is Bevan’s Burial Necklace (2018), which was included in the exhibition The Language of Things: Meaning and Value in Contemporary Jewellery, curated by Sian van Dyk and showing at Lower Hutt’s Dowse Art Museum until late June. A masterclass in contemporary jewellery, van Dyk’s show tells a story about how artists from all over the world have recently engaged with making adornment. Occupying its own small, darkened chamber, Burial Necklace rests, stretched out, inset into the floor, safely behind glass, set upon a black background and dimly lit by fluorescent lights. It occupies a penumbral and private position within the very ground. Lying in a long and slender loop, the necklace appears to be about the length of a human body and is made of clay taken from an Auckland cemetery. The clay has been fashioned into hundreds of tiny beads, each of which is mere millimetres long, evoking multiple acts of rolling and rubbing between the tips of fingers and on the palms of hands. The beads are earthen and unmistakably clay-coloured – they are tiny, multitudinous pieces of the earth mother Papatūānuku, a generative entity from which all life comes and inevitably returns to in death. Kawakawa leaves lie within the installation, the traces of an earlier karakia, and a small station has been built so that one may wash one’s hands after visiting the tapu area. For Bevan, the necklace “encircles the passageway for breath that keeps you living / alive. To place a necklace on the body it is often lifted over one’s head – the head again is a very intimate, personal, vulnerable and culturally to some, a sacred space.”4

Burial Necklace is a reminder of what is at stake with jewellery: frequently, it is a matter of life and death. Generally necklaces outlive those who wear them, their slight forms persist and remain so that they can be passed on and worn by those still living. Simple and contained, Bevan’s necklace is a highly conceptual work. It speaks of the Auckland soil from which it was retrieved as well its location, a cemetery, deliberately left unnamed by the artist, a place where cold clods of clay cradle the bodies of the dead. Quietly accumulative, the beads of the necklace make manifest the many, many different acts of their creation. They are intricate, slight, fragile and precious, gaining value and significance from where they have come from. Each bead might stand in for a moment, a memory or even an instance of remembering. The smallness of the beads seems to make them somehow private or intimate, yet their very material introduces an aspect of the deathly. An object nestled into the ground exhibits a commingling of intimacy and deathliness, one that has the possibility of being worn. This necklace is a deliberately ambiguous object that seems to beg the questions: What is a ‘burial necklace’ and when might one be worn? Is it to be worn by the body, during a tangi? Is it to be worn by the living during an act of burial? Is its excavation and material what makes it a ‘burial’ necklace? What would happen should someone living try it on? Would they die or disappear, as though they stepped into a fairy ring? Bevan herself has additional questions for those who behold the necklace. She asks, “Would you wear this? Should it be worn? And is this appropriate? Would your response change if this clay was connected to a loved one? Is this earth sacred? Or is it just clay?”

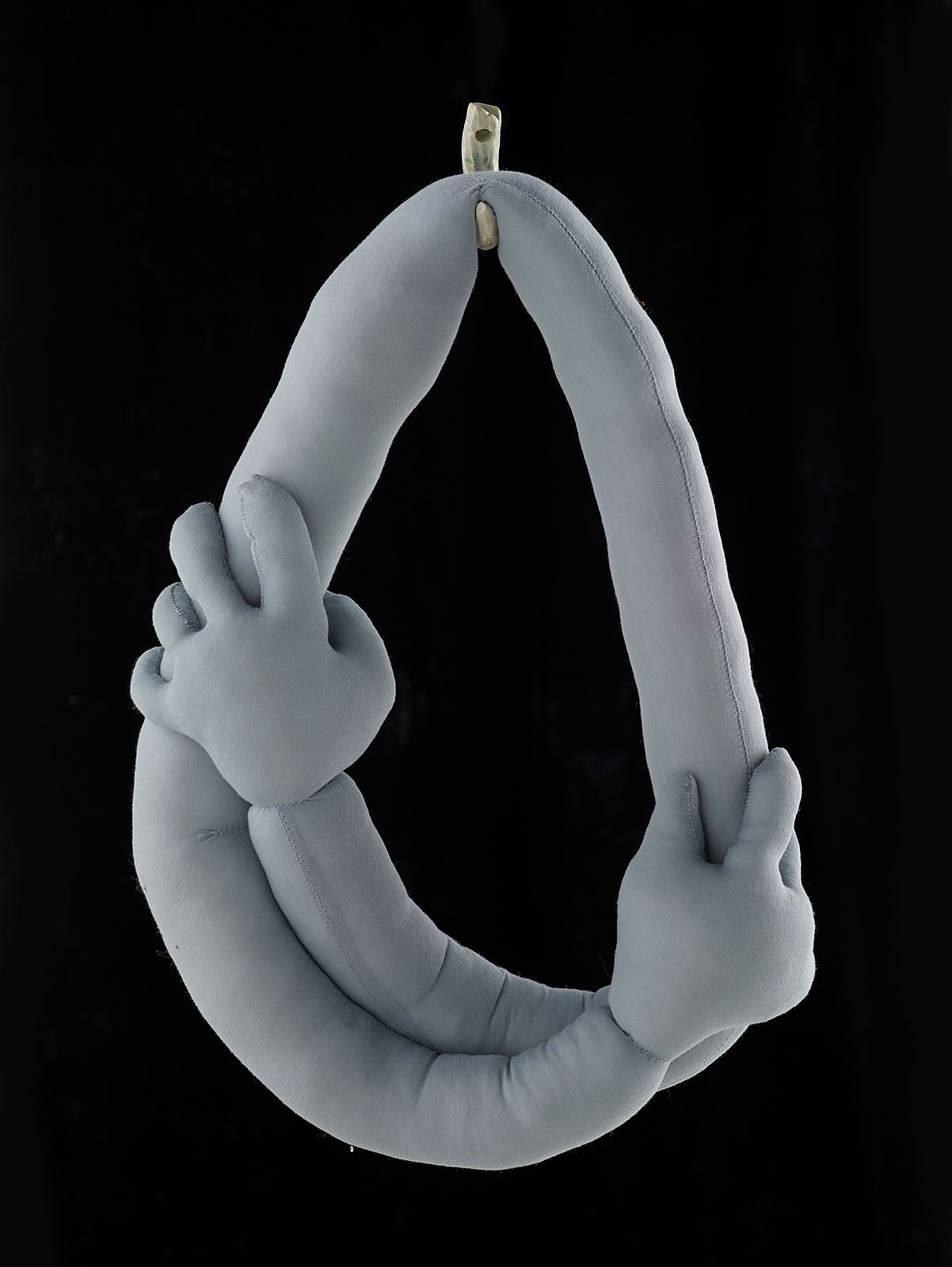

Back above ground, Lisa Walker’s Necklace (2016) is composed of two encircling arms. They clutch each other and are grey-coloured and fuzzy. They remind me of Jim Henson’s creatures in that they seem comfortable and loving. A wonderful connection can also be made between this chiasmic hug and Renee Bevan Necklace. Both instances of neck adornment conflate the necklace with an embrace – with hanging, squeezing and clasping. This particular grey, fuzzy necklace by Walker is accompanied by dozens of others in her retrospective I want to go to my bedroom but I can’t be bothered at the newly opened Toi Art gallery at Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington. The exhibition, curated by Justine Olsen, spans 30 years of the artist’s career. It begins with works made whilst studying goldsmithing in Dunedin, then looking at her practice in Auckland before she moved to Munich in the mid-1990s to study with art-jewellery demigod Otto Künzli – a figure who is also revered by Bevan. The final section of the exhibition displays works made in Wellington since 2009. Walker’s necklaces and pendants either float suspended in boxy vitrines or lie patiently upon vari-levelled plinths. A chalky palette of soft blue-grey and bubblegum pink means the labyrinthine walls and plinths evoke a tasteful subtlety along with the feeling of a punkish girl’s bedroom. Similar to Monu’s exhibition, one wall displays large, risographed photographs (made in collaboration with London-based design studio Äbake), each showing an individual sporting a piece made by Walker. These images show the various ways in which the works are particularised, activated and completed by those who wear them. This enables Walker’s pieces to be seen as they might be worn, something that is impossible when they are trapped within a vitrine.

Both instances of neck adornment conflate the necklace with an embrace – with hanging, squeezing and clasping.

If I may quote a quote of a quote, if “some people want to run things, other things want to run,” then Walker is very much an artist who wants to let things run– and perhaps even run with them, or after them.5 The way in which Walker’s pieces are constructed seems to indicate a ‘declension,’ a deferral, or submission towards ‘thingliness.’6 There seems to have been a surrender to the autonomy and agency of things, as though the artist has listened to them tell her what they might become. In terms of neck adornment, Walker stretches such a concept as far as it can possibly go. I want to go to my bedroom but I can’t be bothered is fecund with examples of the way in which Walker aggregates things in order to create circular forms, as well as the way in which she isolates things, perforates them and threads a string through them in order to make them into pendants. Within a wilderness of independent things, Walker’s self-assured handling is a way of activating stuff. Annular forms are made from: a ribbon punctuated by cardboard circles and bobbles made of sticky tape, a blue velvet balaclava (à la Pussy Riot), orange-coloured and octopus-shaped stuffed fabric, woollen finger-puppets, taxidermy ducklings, even driftwood and steel. What unites these necklaces and pendant forms is the operation of hanging, harking back to the brachiators hanging from their trees. As Walker has demonstrated over the years, a multitude of things might hang from a string and be called a necklace. Such things include: a plastic bottle containing a pearl and a fart, mussel shells, mobile phones, a laptop, wooden goblets, an anatomical hand model, offcuts from a studio floor, pounamu, pāua shell, a skateboard, exhibition catalogues, the back of an office chair, golden letters, a piece of steel incised and cut to look like Bart Simpson, a stack of plastic vampire teeth held together by a silver frame.

There seems to have been a surrender to the autonomy and agency of things, as though the artist has listened to them tell her what they might become.

There is nothing hierarchical about the way Walker approaches stuff, things, objects and materials, as they are all grist to her adornment-making mill. Pendant (2008) is a conglomerate of ceramic, brass, freshwater pearl, mother-of-pearl, raw rubies, plastic, glue, wood, acrylic paint, thread and silver. An artist attuned to what Canadian philosopher Peter Gratton describes as “the strange power of things,” Walker creates pieces that involve assemblage, the gathering together of things that combine to suggest customary forms of adornment such as a brooch, a bracelet, a pendant, a necklace – yet they also function as mobile, wearable little sculptures or installations.7 To quote Gratton again, Walker seems to be “always in concert in and through other things.”8

In 2001 Walker opined, “The strange worlds of contemporary jewellery would fit perfectly into contemporary art. Someday, they’ll finally realise this.”9 Indeed, the practices of Monū and Bevan as well as Walker are testament to the current intermingling of these two worlds. Gathering together works by these three artists demonstrates how the convention of neck adornment might be realised in ways that are deeply conceptual and contemporary. There is the possibility for one to slightly bow and lift over one’s head a necklace, pendant or garland made of petals, twigs, plastic, pearls, raw rubies or clay and wear it upon a collarbone, in the space between one’s arms. Yet there is equally the possibility of crouching down, standing still or craning one’s neck upwards and simply gazing upon such a piece as a little installation in itself.

1. John Berger, “Ape Theatre,” in Why Look at Animals? (London: Penguin Books, 2009), 46.

2. Sione Monū, personal communication, May 28, 2018.

3. Fresh Gallery Ōtara, “KAHOA KAKALA: SIONE MONU, 8 August – 9 September 2017” (room sheet).

4. Renee Bevan, personal communication, May 25, 2018.

5. Fred Moten and Stefano Harney quoted by André Lepecki, Singularities: Dance in the Age of Performance (Abingdon, Oxon and New York: Routledge, 2016), 29.

6. Lepecki, Singularities, 33, 34, 36.

7. Peter Gratton, Speculative Realism: Problems and Prospects (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2014), 110.

8. Grattton, Speculative Realism, 112.

9. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, “Lisa Walker: I want to go to my bedroom but I can’t be bothered” (room sheet).

With thanks to Jasmine Te Hira, Elle Loui August, Sione Monū, Renee Bevan, Alexandra Grace and Sian van Dyk at The Dowse, Steph McDonald and Justine Olsen from Te Papa and Lisa Walker.

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with Blumhardt Foundation. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.