Whakanuia: 10 Contemporary Muslim Poets We Love

Contemporary Muslim poets whose work we love, admire or would like to read more of.

In January 2017, when Trump signed an executive order imposing an anti-Muslim travel ban, American poet Kaveh Akbar – who was born in Tehran, Iran – responded by tweeting poems from other writers from affected countries: Libya, Iraq, Iran, Sudan, Somalia, Yemen and Syria. This fitting act of solidarity was characteristic of Akbar, who, as well as being a wonderful poet himself, regularly lifts up and champions the work of other writers.

In the same spirit – in defiance against white supremacy and in solidarity against the recent terror attacks on the Muslim community here in Aotearoa – here are a few contemporary Muslim poets (writing in English) whose work we love, admire or would like to read more of.

Mohamed Hassan

The power of Mohamed Hassan’s poetry is equally evident in his spoken word and on the page. Also an award-winning journalist, Hassan was the 2015 New Zealand National Slam Champion and represented New Zealand at the Individual World Poetry Slam in 2016. In 2016, he also released his debut collection of poetry, A Felling Of Things. Copies are difficult to locate, but he has several pieces available online which you can enjoy immediately.

“My mother is a warrior…” From the very first words of ‘The Muslim Women Who Raised Us’, Hassan’s fierce love, pride and respect for his mother and sister just shines. This piece is a testimony to the bravery and determination of Kiwi Muslim women:

The women in my family are dreamers, revolutionaries, kings and queens / they are because they need to be / because we need them to be / we need them.

I spent 19 years mispronouncing my name so others will be able to say it. I wrote this poem about learning/unlearning that habit. pic.twitter.com/OZy1R0c9WZ

— Mohamed Hassan (@MHassan_1) September 27, 2018

Equally personal and poignant is ‘(Un)learning My Name’, in which Hassan scrupulously examines the mechanism of internalised racism, and the significance that our language and our pronunciation have for upholding identity: “it feels like I have stolen / something / back.”

Having heard Hassan, it is easy to imagine the rhythm and timbre with which he would give voice to his new poem, ‘National Anthem’, published recently on The Spinoff’s Friday Poem. Hassan is also a contributor to The Pantograph Punch: read his essay ‘When do We Get to Speak?’ here.

Halal If You Hear Me – how good is that title! – is a new anthology of writing by Muslim women, Genderqueer, and Trans writers due out this month. One co-editor of the anthology is Pakistani-Kashmiri-American poet Fatimah Asghar, author of If They Come For Us (One World, 2018). Multi-talented Asghar is also the writer and co-creator of the web series Brown Girls, which explores queerness and friendships between women of colour, and her essay ‘Finding the Hammam’ – published this month in Poetry magazine as part of a special Halal If You Hear Me section – is a brilliant and moving piece of writing about what it means to be a Muslim woman writing poetry.

In a short essay on Glamour about her web series, Asghar writes, “I’m not a sitcom writer; I prefer dark comedy, diving into microaggressions and cultural misunderstandings.” There are moments of comedy in Asghar’s poetry, too, but overall it’s more serious. A short note about the India/Pakistan Partition sets the context for the poems that follow, and the word ‘partition’ echoes loudly throughout, appearing as a title for several poems. The repetition serves to emphasise how the word itself, so ordinary, neutral and benign-sounding, so surgically neat, is sharply at odds with the scale of pain and loss in the real events it signifies.

Asghar addresses this directly in one of her poems:

If I say the word enough I can write myself out of it:

take the driver rolling down that partition, please

…

My god partitions sunlight into many rays. They dance,

partitioned, on the sidewalk, against the trees, my skin.

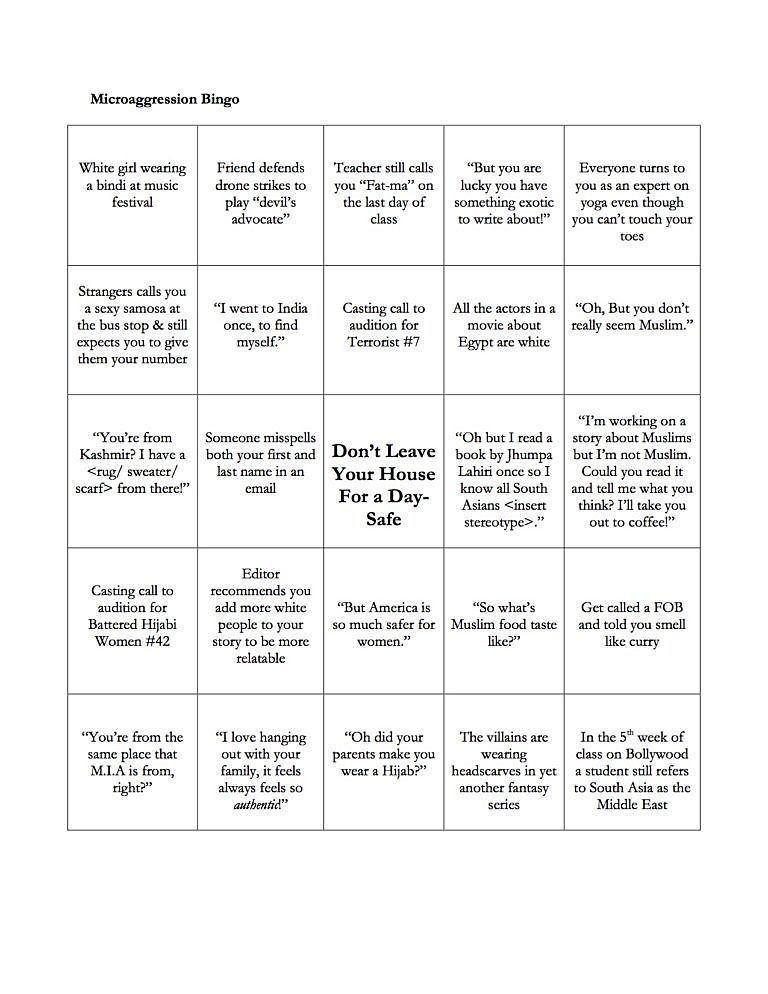

Asghar is extremely dextrous with poetic form. A handful of concrete poems are among the best pieces in the book, including the devastating ‘Script for Child Services: A Floor Plan’, the razor-sharp ‘Microagression Bingo’ and the haunting ‘Map Home’. But the playfulness that comes from the visual schema of a game or a puzzle in these pieces is offset by ominousness – if these poems are a game, it is not one you can win.

Despite the heavy presence and significance of the past, If They Come For Us is also rooted firmly in the contemporary, with millennial touch-points like cucumber body mist and Beanie Babies. The poems in If They Come For Us are both proud and vulnerable; they reveal a flawed and contradictory self, complicated by the half-truths we tell ourselves and others when the truth is too hard. Other particularly outstanding poems include ‘Haram’, about hair and modesty; ‘Boy’, about gender identity; ‘To prevent hypothermia’, about friendship and belonging; and ‘Oil’ – about identity and racism in 9/11-era America. The richly sensory poem ‘If They Should Come for Us’ concludes the book on a note of defiance and unity.

My name is Safia. I’m a Sagittarius. I share a birthday with Beethoven and the rapper Flo Rida. Here are some poems that have nothing to do with that.

This is how Sudanese-American poet Safia Elhillo – the other co-editor of Halal If You Hear Me – introduces herself, before going on to deliver, with unflinching force, poems from an evolving series she calls ‘The Alien Suite’.

As one keen-eyed YouTube commenter has noted, Elhillo doesn’t share a birthday with Flo Rida at all, and Beethoven’s exact birthday isn’t known. This hardly matters. Whatever Elhillo decides to tell us, we should listen.

Did our mothers invent loneliness? Or did it make them our mothers?

– from ‘an inheritance’

they’re worried no one will marry me i have an accent in every language

i want to be left alone but that’s not how you make grandchildren

i can’t go home with you home is a place in time

(that’s not how you get me to dance)

i’m not from here i’m not from anywhere

–from ‘date night with abdelhalim hafez’

Elhillo’s first full-length collection, The January Children (University of Nebraska Press, 2017), won the 2016 Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets and a 2018 Arab American Book Award. She is widely published online – I particularly recommend ‘Self-Portrait With No Flag’, ‘what i learned in the fire’ and ‘still life with the accent’:

Elhillo’s bilingualism is vital to her writing. As Matthew Shenoda observes, “Writing in English with deep Arabic-language inflections, she moves between the two languages to not only illustrate a cultural perspective but critique the space of race and the Sudanese position in relation to the north of Africa.” Shenoda goes on to say, “From the start this idea that everything lost will be named, and not that it will come back but live forever, is perhaps deeply emblematic of the position Elhillo’s generation takes on ideas of migration and diaspora.”

Alongside Asghar, Elhillo has also just published a new essay, ‘Good Muslim/Bad Muslim’, in Poetry magazine – it’s a must read. She writes, “I’ve been afraid, forever, of performing my identity incorrectly. My Muslimness, my Sudaneseness, my Americanness, my Blackness, my womanhood, all of it…I looked to books to teach me how people were with each other – how they talked, how they touched, how they played, how they trusted, how they mourned.”

American poet Hanif Abdurraqib is a master of observing and describing the social world around him. Reading his work and listening to him read, the real people and events that inform his writing feel immediate and vivid, almost within reach. His skill at creating this feeling is very evident in poems such as ‘It’s Not Like Nikola Tesla Knew All of Those People Were Going to Die’, ‘It’s Just That I’m Not Really Into Politics’ and ‘I guess it has been a pretty good year’:

The boys in Ohio these days / ride bikes without helmets / they drive fast down that road / shoot bb guns into the darkness / break themselves on the football field on Friday nights / or climb water towers / and dream of cities like the one I am from / where black boys are promised nothing at birth / but a suit to be worn while being wed / a suit to be worn while being lowered into the ground / and a mother who will never stop whispering prayers for one to be needed before the other.

–from ‘I guess it has been a pretty good year’

Abdurraqib makes it onto this list because of his poetry, which is indeed very good, but I actually think it’s the essay form in which he shines brightest. His observation of social power and constructs (see, for example, his perceptive and personal short essay on growing up and race, ‘On College’) operates in dialogue with his keen observation of aesthetics and music. His diverse interests – from punk and emo to Motown and hip hop – make him a dynamic and compelling critic. His essay on Muslim pop star Zayn Malik is just a beautiful piece of writing:

I know what it is to go from invisible to threatening and to wish for invisibility again…There are things from which we can’t untether ourselves, things that stay with us even when we have become so much else without them.

…and more

‘This Is Not A Humanising Poem’ by UK poet Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan. Performed in the 2017 Roundhouse Poetry Slam, the poem has gained 2 million online views, was short-listed for the 2018 Outspoken Prize for Performance Poetry and has been translated into German, Italian, Spanish, Icelandic and Urdu. Manzoor-Khan blogs at The Brown Hijabi.

‘Forgetting to Name our Daughters’ is from Australian poet Sara Saleh’s first poetry collection, Wasting the Milk in the Summer, self published in late 2016. The book explores themes of displacement (from place, from self), migration, identity and women. Saleh was a 2015 Australian Poetry Slam NSW State Finalist, and co-founded the Dubai Poetry Slam in 2015, and its sister slam in Amman, Jordan.

The Hijab Files (Giramondo Publishing, 2018) is a debut poetry collection from Australian poet Maryam Azam, who describes the book as “a snapshot in the life and times of a young woman in Western Sydney.” Azam has been interviewed in Liminal.

‘The Master’s House’ by Iranian-American poet Solmaz Sharif.

‘Ghazal: With Prayer’ by Lebanese poet by Zeina Hashem Beck.

‘300 Goats’ by Palestinian-American poet Naomi Shihab Nye.

This is an impossibly short selection – and apologetically American-heavy. To find more superb Muslim poets from various nations, including in translation, it’s worth exploring Kaveh Akbar’s full Twitter thread, this Twitter thread by Jeremy Radin and this list of 11 Palestinian-American poets at Entropy. And for fiction, check out 10 novels by Muslim women recommended at Nylon.