On the conditions and possibilities of New Zealand performance art taking New York by storm

Kim Choe reports back from the New Zealand New Performance Festival

If you were to open the 23 March issue of New York Magazine and flick to its famed ‘Approval Matrix’, you would have found a small but perfectly formed reference to New Zealand playwright and actor Arthur Meek.

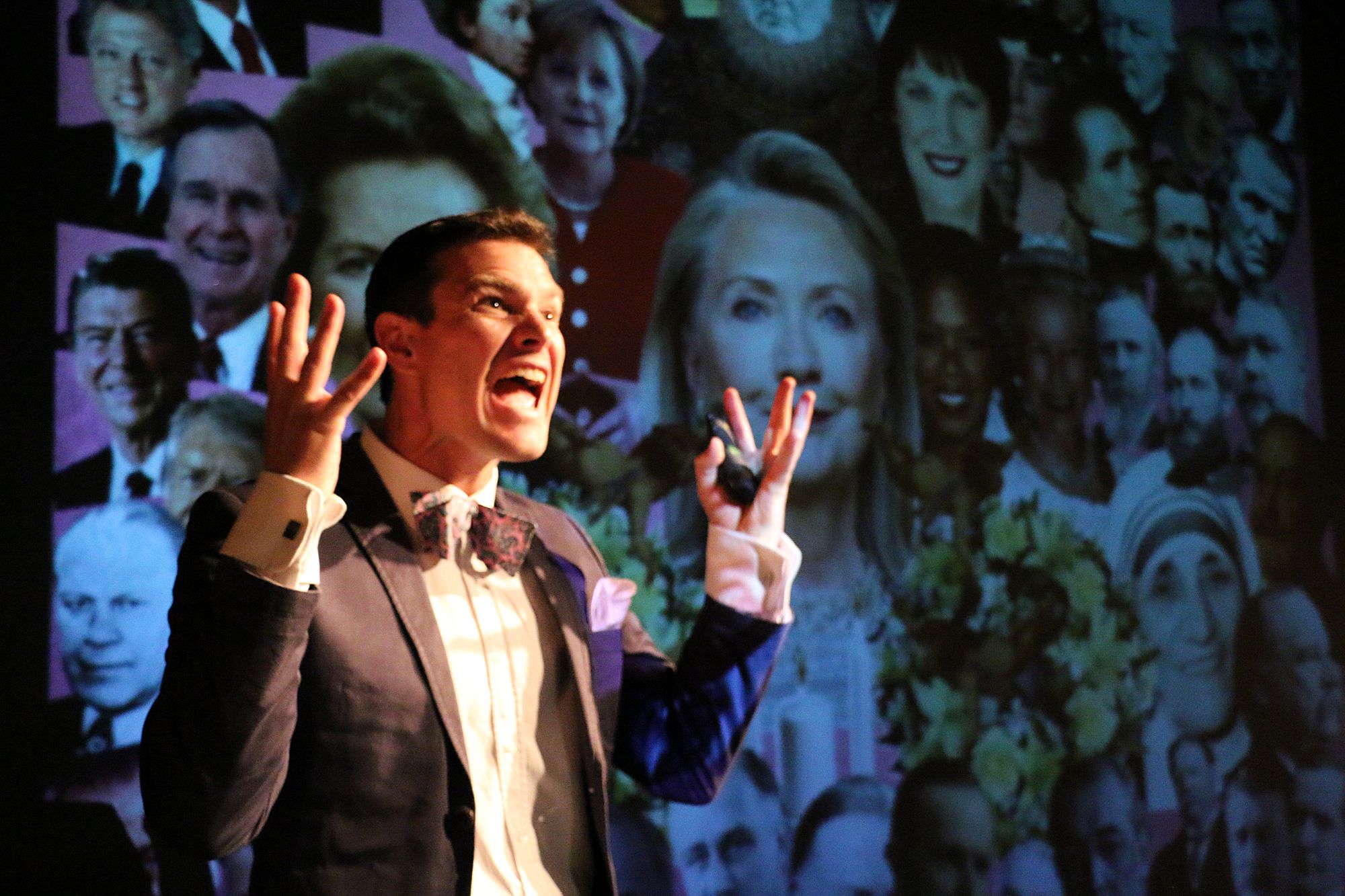

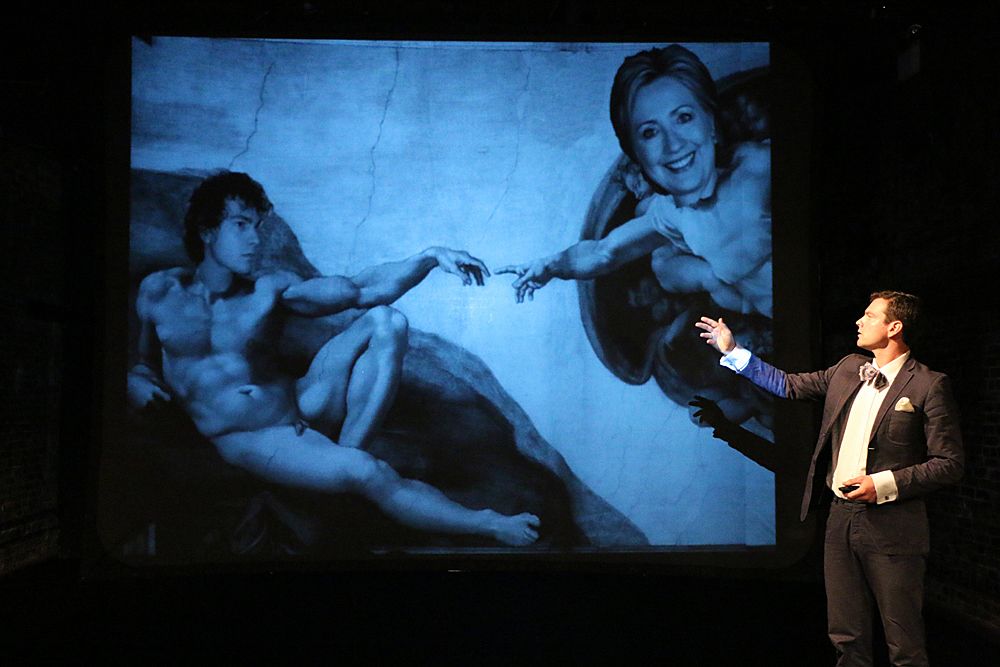

The magazine’s “deliberately oversimplified guide to who falls where on our taste hierarchies” proclaimed Meek’s show, On the Conditions and Possibilities of Hillary Clinton Taking Me as Her Young Lover, as “demented”, and placed it towards the ‘brilliant’ and ‘lowbrow’ ends of the spectrum - nestled happily in between Iggy Azalea and Robert Durst.

The mention ran a mere 21 words, but spoke much more about the immediate impact Meek and his fellow artists had during the New Zealand New Performance Festival’s recent three-week residency at New York’s La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club.

Billing itself as a showcase of “witty, direct and profoundly Kiwi” works, the showcase faced the enormous challenge of trying to be seen in a city described by the festival’s Artistic Director Sam Trubridge as being in a constant state of “permafestival.”

“In New York, a lot rests on a name,” he said. “The cache that goes with a name will draw a lot of people.”

So Trubridge banked heavily on Brand New Zealand to attract a local audience, hoping their knowledge of our mythical landscapes from Hollywood films, our deadpan humour from comedy TV series, or our penchant for brooding electro-pop, courtesy of a certain teen popstar, would pique their desire to view the country through a new lens.

“I’ve described New Zealand as a dream factory, and this programme of works comes from that dream factory but really shows a different angle on it all,” he said. “It’s not playing into the usual kind of expectations; it’s certainly not a Tolkien film. And it’s certainly not playing into any kind of stereotyped images of New Zealand.”

In fact, many of the festival’s nine offerings - largely originating from the Wellington theatre scene and companies like The Playground Collective and Binge Culture - revolved around subjects immediately recognisable to many Americans: their politician in On the Conditions and Possibilities of Hillary Clinton Taking Me as Her Young Lover; their jazz musician in Chet Baker: Like Someone in Love; their hip-hop music in So-So Gangsta; their Freedom of Information Act in Listening Posts.

“New Zealand has this perspective that comes from the edges of the map, and sometimes our perspectives are quite surprising for people,” Trubridge reasoned.

Meek, who co-wrote On the Conditions and Possibilities of Hillary Clinton Taking Me as Her Young Lover with Geoff Pinfield, was initially more apprehensive. The outlandish yet philosophically sound comedy lecture expounded Clinton’s need and desire to romance naive academic Richard Meros (Meek) in order to improve her presidential prospects. A previous version of the play, with Helen Clark as the subject, had been enthusiastically received in New Zealand - but Meek feared Americans might be more protective of their own.

“The thing that I was worried about was that the audiences would not want to hear a New Zealander talking about American politics or anything like that,” he said. “But it turns out that’s fine.”

One reviewer did take issue with the “fair amount of vocabulary that American audiences won’t generally understand”. However, the complaint seemed isolated, with nobody I spoke to reporting any comprehension issues beyond having to overcome the general amusement of Meek’s distinct yet well-enunciated Kiwi accent.

Audience member Laura Cornwall remarked how refreshing it was to see American politics presented “with no baggage”. Her friend, Philip Walter, was impressed by Meek’s encyclopedic command of the US political landscape, particularly his ability to recite the names of all 44 Presidents in reverse chronological order.

“It’s embarrassing how little we know about our own politics,” Walter bemoaned.

The crowd clearly enjoyed playing along with Meros’ hypothesis that without him at Clinton’s side (or rather, in her bed) enhancing her presidential chances, the country would “continue lurching between the donkey and the elephant like a drunken man at the zoo”.

The reasoning applied to the Clinton scenario is the very same that Meros used in his efforts to woo Prime Minister Clark ahead of the 2008 General Election. Even though the modus operandi was familiar to me the second time around, Meek and Pinfield’s knack for crafting precise prose peppered with well-executed pop culture references made it feel fresh and relevant, without resorting to tokenism. The character of Meros walked a fine, endearing line between arrogance and haplessness, such that it felt easy to want him to succeed in his conquest.

Meek has no idea how he ended up in New York Magazine. “It’s basically a miracle,” he enthused. “It pretty much justifies the time and expense of coming over for the trip and it’s just opened a whole lot of doors straight away for me in terms of people I’ve been meeting with.”

The mention prompted him to schedule an additional performance of the work later this month in order to court people who missed it the first time around. He and Pinfield have their sights set on a run in a more commercial venue - the prestigious New York Public Theatre is mentioned. They would also like to take it on a tour of presidential campaign proportions, setting themselves a goal of 200 performances in the next year.

Hillary Clinton isn’t the only show for which the festival opened up new possibilities. Trubridge’s work Sleep/Wake has had interest from the Istanbul Biennale, and David Goldthorpe has venues interested in his jazz musical Chet Baker: Like Someone in Love.

Like Meek, Goldthorpe was particularly nervous about presenting a story about an American to an American audience. For the first time in the eight years he has been performing the show, there were people in the audience - and in his accompanying jazz trio - with personal connections to Baker, a jazz trumpeter and vocalist who struggled with drug addiction throughout his professional life.

“With a lot of the subject matter being quite delicate...you never know who you’re going to offend,” Goldthorpe worried. “It made me particularly pleased and proud that I’d spent all the time combing through biographies and facts to make sure I wasn’t misrepresenting him.”

The show blended narrated anecdotes with performances of Chet Baker standards. The transitions between the two elements occasionally felt stilted, but Goldthorpe’s portrayal of Baker as a self-centred genius at the mercy of a drug addiction was dark, powerful and intimate.

A large part of the New Performance Festival’s success in getting its artists noticed can be attributed to the pedigree of its host, La MaMa. The theatre has been at the heart of the East Village’s creative community since 1961, back when bohemia and counterculture were rampant and organic, a way of life rather than a fleeting fascination.

The area has more of an eclectic-chic feel about it these days, but La MaMa remains its grand dame: its shabby, cavernous spaces heave with memories of its hedonistic, hippy days. You can imagine the songs from one of its most famous exports, Hair, meandering down the sprawling wooden staircases. Each performance is quaintly introduced by a steward of sorts, who stumbles over the inordinately long show titles, points out the fire exits, and reminds us multiple times to take our own cans and bottles out of the theatre for recycling.

The theatre’s track record for fostering emerging talent - it boasts Robert De Niro, Al Pacino and Whoopi Goldberg among its notable alumni - means people take notice of the works it chooses to showcase. Before the festival even started the Kiwi crowd had gained prominent coverage in alternative weekly The Village Voice and The New York Times.

Even so, shows in the early part of the programme had difficulty selling seats. Meek said audiences for Hillary Clinton, which ran in the festival’s first four days, only reached around 50 percent capacity at some shows. He was fortunate that those who did attend included agents, and whoever it was that held some sway at The New Yorker, but said a few more people would have been nice, as a matter of pride more than anything else.

As chatter around the festival increased, however, so did the audiences. By the time The Playground Collective’s All Your Wants and Needs Fulfilled Forever played its last show in the third weekend, the venue was hurriedly having to unfold extra chairs to meet demand. Perhaps the image that adorned the Village Voice’s coverage – of its main character Simon (Eli Kent) passionately locking lips with a bald mannequin – helped bring in a few curious punters.

This was among the festival’s more distinctly ‘Kiwi’ offerings, being set in the Wellington suburb of Te Aro and featuring an appearance by Mr 4 Square. Yet, of the shows I attended, it got the most enthusiastic reception. The humour, both physical and scripted, was accessible without being overblown. A strong narrative exploring Simon’s attempt to cope with loss through immersing himself in his television wove together the more allegorical aspects of the performance, making for a tidy yet original piece.

Remarkably, La MaMa booked the entire festival without seeing a single work. As Trubridge tells it, the theatre “took a big punt”, acting on the recommendation of an agent who’d talked to another agent who’d seen his work, Sleep/Wake, in 2009. La MaMa invited Trubridge to bring the show to New York; he suggested he bring a few friends along too and they agreed, giving him free reign over the programme.

The theatre’s Artistic Director, Mia Yoo, said she was sold on the uniqueness of the proposition.

“It’s rare to see contemporary performance art from New Zealand and that’s one of the reasons why we all jumped off the cliff to see what would happen,” she said. “The work was really special and unique and very diverse in terms of the actual artistic pieces that were presented. The folks involved as individuals really suited our ethos here, where everybody takes out the garbage, everybody finds a way to make things happen. It’s a very collaborative energy within the group.”

For Trubridge, that collaboration made perfect sense since many of the people involved in Sleep/Wake also had their own projects. “It would allow a whole community to be shared for what is pretty much the price of one show,” he said.

It would also create a more condensed, concentrated experience, not just for audiences but for the artists as well. Most worked across multiple projects, acting, designing sets, stage managing and helping with publicity as required.

“It’s precisely the sort of culture we’ve created in New Zealand, particularly with Wellington being such a small city, that we do work on each other’s works and are constantly building a city-wide community or company of theatre artists,” Trubridge said.

Despite all these efficiencies, the festival was nonetheless a significant financial undertaking. Creative New Zealand awarded $40,643 in grants to cover travel and set freighting costs for three of the acts; crowdfunding through arts-focused platform Boosted netted $15,555 more for freight and hiring a New York-based publicity agent. Movie night fundraisers added to the coffers but all other travel and accommodation costs were footed by individuals.

Trubridge is adamant the festival’s value will reach far beyond what can be calculated in modest ticket takings, and even further than the opportunities now presenting themselves for some of the shows.

“All the artists are engaging with the New York community of artists, and are then able to return to Wellington and New Zealand with this experience, and hopefully have their work challenged and their perspectives challenged by what they’ve encountered here. I think that for me is the most important outcome.”

Both he and La MaMa are eager to mount the festival again, and it certainly seems like the inaugural one found enough new fans of New Zealand theatre to make it easier to gain traction a second time around. However, Trubridge recognises the need for a more sustainable financial model. He would like to see Creative New Zealand come on board in a broader capacity than just funding individual works, he says, so that artists don’t have to dip into their own pockets to take part.

“We can’t just stay in New Zealand and make work for each other, which is a real risk of living in New Zealand. We need to go overseas and we need to share our experiences of our people, and develop cultural dialogues to exist in this world and to be an active part of it.”

* Lead image courtesy Goldthorpe Creative.