A Dramaturgy of Sound: On Complicite's 'The Encounter' and Being Alone Together

For the first time ever, groundbreaking British theatre company Complicite performs in New Zealand in March as part of the Auckland Arts Festival. Kate Prior watches their Amazonian epic The Encounter in two different places and times and explores in the undergrowth.

For the first time ever, groundbreaking British theatre company Complicite performs in New Zealand in March as part of the Auckland Arts Festival. Kate Prior gets sonically submerged in their audio epic The Encounter and situates it in the work of this mercurial 30 year-old company.

LOREN: First contact. What a shot, that’s great. Ideal first contact.

My first encounter with Complicite’s The Encounter was live on my laptop screen, listening with headphones at a friend’s home in Ngaio on Wednesday 2 March 2016 at 8.30am. This was the exact time the performance – in a first for the company – was live broadcast on YouTube from London’s Barbican Centre. The broadcast would be online for a week, but it was extremely important to me to watch it at the exact time the creator/performer Simon McBurney would be spitting on a microphone on stage on a Tuesday evening over 18,000 kilometres away.

In 1983, three graduates from the Paris theatre school of Jacques Lecoq – Simon McBurney, Annabel Arden and Marcello Magni – formed a company. They called it Théâtre de la Complicité, and it was “an act of resistance”. In Britain at that time, they were seeing nothing of the theatre they wanted to make; British theatre was still tied to the word, and this determined a certain audience. “Since the arrival of television, theatre had become more and more an upper-middle-class activity”, McBurney noted about the company’s genesis. “There was that tradition of theatre - very class-determined, literary, intellectual - and we didn’t feel part of that”. The process of devising work (creating work from the rehearsal room floor rather than an extant script) was at the time still relatively rare in the UK. But McBurney, Arden and Magni had emerged from a school of commedia dell’arte, mime and physical theatre with an ethos that ‘play’ mattered more than ‘the play’. So they set about creating their continental theatre in England.

Now led by artistic director Simon McBurney, with a perennially changing cast of collaborators, the 30-year-old theatre company is a rangy, shifting entity whose name has by turns morphed from Théâtre de Complicité, to Theatre de Complicite to Complicité, and now, Complicite. The mercurial nature of the name alone is symptomatic of a company whose aesthetic preoccupations are hard to pin down, and the current name’s deliberate nonspecificity (is it spoken like the French ‘complicité’ or English ‘complicity’?) reflects a company with one foot on British shores and the other on the continent. It’s true that while the company has fundamentally shifted the face of British theatre over the last 30 years, they’ve always remained outside a British theatre tradition. As theatre director Peter Brook once said, “The English have a fine, long and wonderful tradition. Simon McBurney and Complicite are not part of it”.

The English have a fine, long and wonderful tradition. Simon McBurney and Complicite are not part of it.

Like everyone else who went to drama school, my first encounter with Complicite was at drama school. The company was among the group of contemporary theatre greats with distant European-sounding names: Ariane Mnouchkine and her Théâtre du Soleil, Peter Brook, Pina Bausch, Eugenio Barba… But something about Complicite felt closer. This is because if you went to Toi Whakaari: New Zealand Drama School between the years of 1997-2012, you were in daily movement training with a tutor who himself was a graduate of the same school of Jacques Lecoq. Everything we learnt had a foundation in Lecoq’s physical pedagogy. So, sharing as we did a similar theatre whakapapa, Simon McBurney and team seemed to me to be imagined distant whānau. This year marks the first live encounter New Zealand audiences will have with this company.

*

When I finished watching that live performance on my laptop screen in Ngaio, I emerged from my private world in annoying theatre evangelist mode. Yes, theatre on screen is usually pretty awful and shouldn’t be done, but this was different, this was a one-off wonder, everyone I saw that week was going to watch The Encounter.

Friend: What’s The Encounter?

Kate: Oh my god it’s like nothing you’ve seen before.

Friend: No I mean, what’s it about?

Kate: I don’t know. Well, okay, it’s about time and our assumptions about the way we live and how we order and organise our lives in the West and the meanings we ascribe to that. And it’s about being alone and on the outside. And it’s about the meanings we’re passing on, and about waste and material goods and how we’re living and what we’re doing to the planet. But it’s not a lesson. It’s a question. And there’s a little girl in it who sounds just like my niece.

Friend: No but what’s the story?

Kate: Oh. It’s about a photographer. I photographer who goes into the Amazon and gets lost.

*

Simon McBurney was given Petru Popescu’s book Amazon Beaming in 1994. Popescu tells the story of traveller and National Geographic photographer Loren McIntyre, who wants to find the source of the Amazon. Instead of that assignment, National Geographic sends him to capture images of the Mayoruna, a tribe that had supposedly disappeared and escaped the persistent threat of acculturation, but had more recently been sighted. McIntyre is dropped into Amazon rainforest – 400 miles of it in every direction – to find them. After successfully capturing the tribe on celluloid, McIntyre’s camera and equipment are destroyed, along with his whole reason for being there. Forced to shift his perspective to survive, he is virtually imprisoned by the Mayoruna as they trek upriver, destroying their belongings as they go. They are searching for Time’s beginning, which for them is found at the source of the Amazon.

McBurney calls this the ‘once upon a time story’ of The Encounter. But that is the map, not the terrain; he then layers this story with his own, and cradles both in a mind-bending form by means of binaural sound technology that weaves through you like a texture, places you alone amid a group of people and creates ghosts in your imagination.

So strong is the illusion that often your brain can’t stop your body turning to the right to see who just walked in at the back of the theatre. You know the door isn’t real, you know you don’t have to look. But you have to. Wherever that head is, that’s where you are.

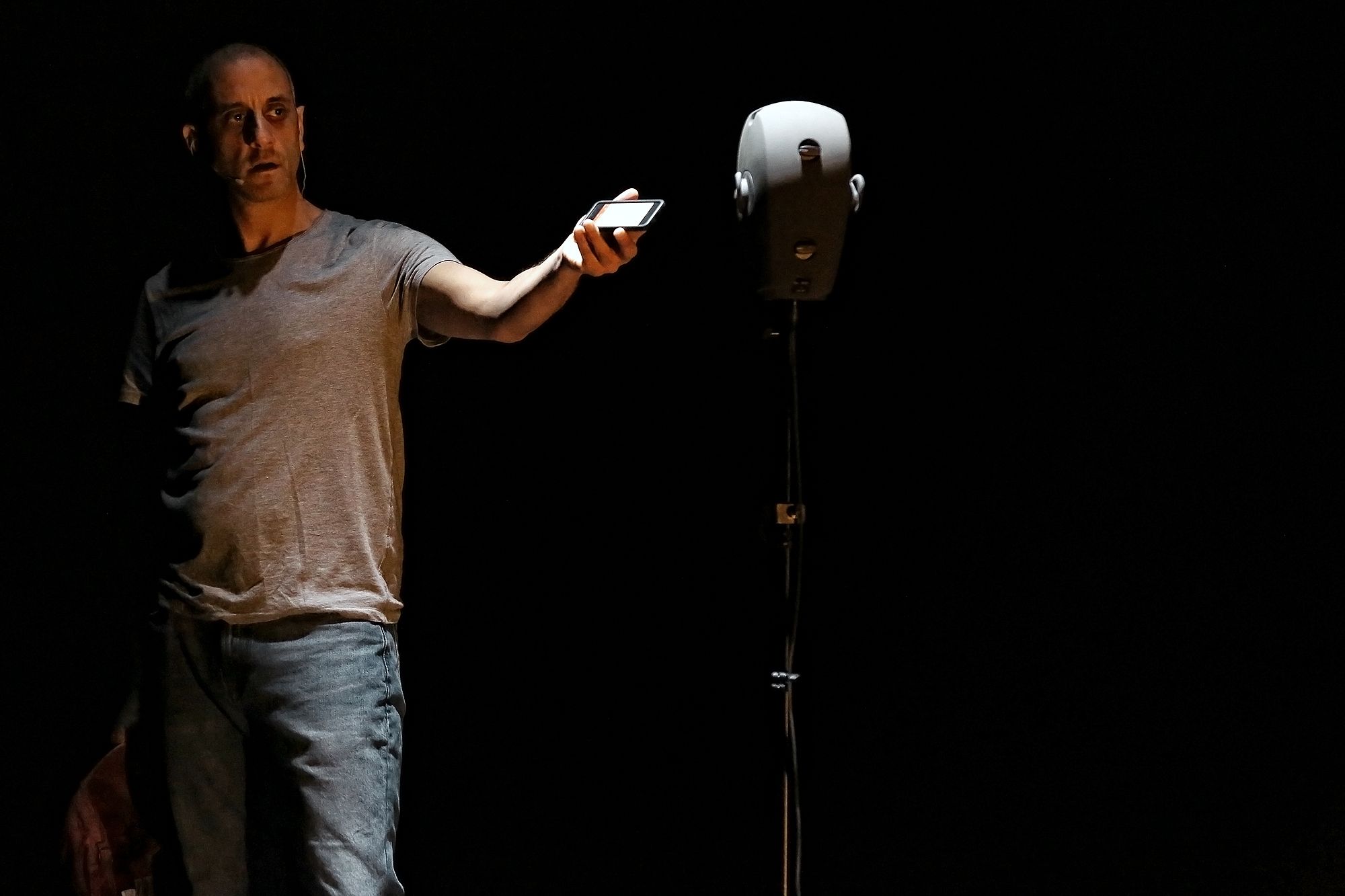

The entire audience of The Encounter wear high-quality Sennheiser headphones. Onstage there’s a binaural microphone shaped like a human head. The technology of the binaural head mimics the biological makeup of the human ear, and picks up sound on a three-dimensional level. This means you really hear a mosquito circling your own head, or a door closing to your right. So strong is the illusion that often your brain can’t stop your body turning to the right to see who just walked in at the back of the theatre. You know the door isn’t real, you know you don’t have to look. But you have to. Wherever that head is, that’s where you are.

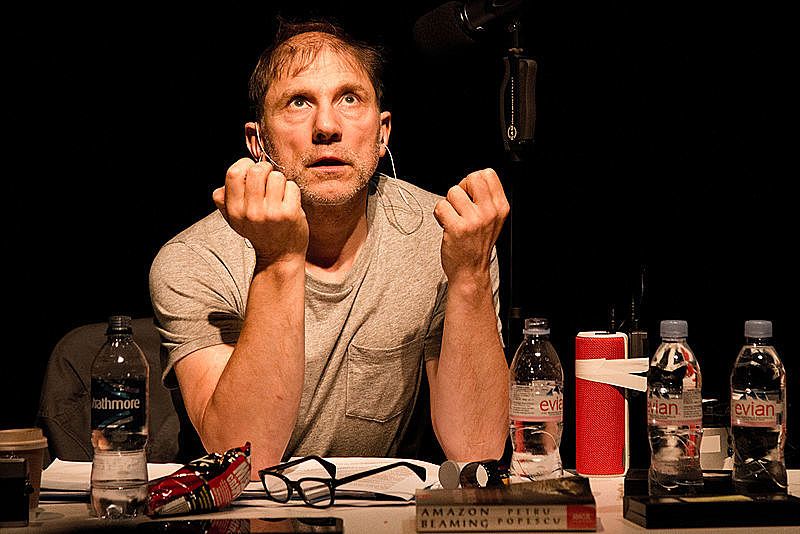

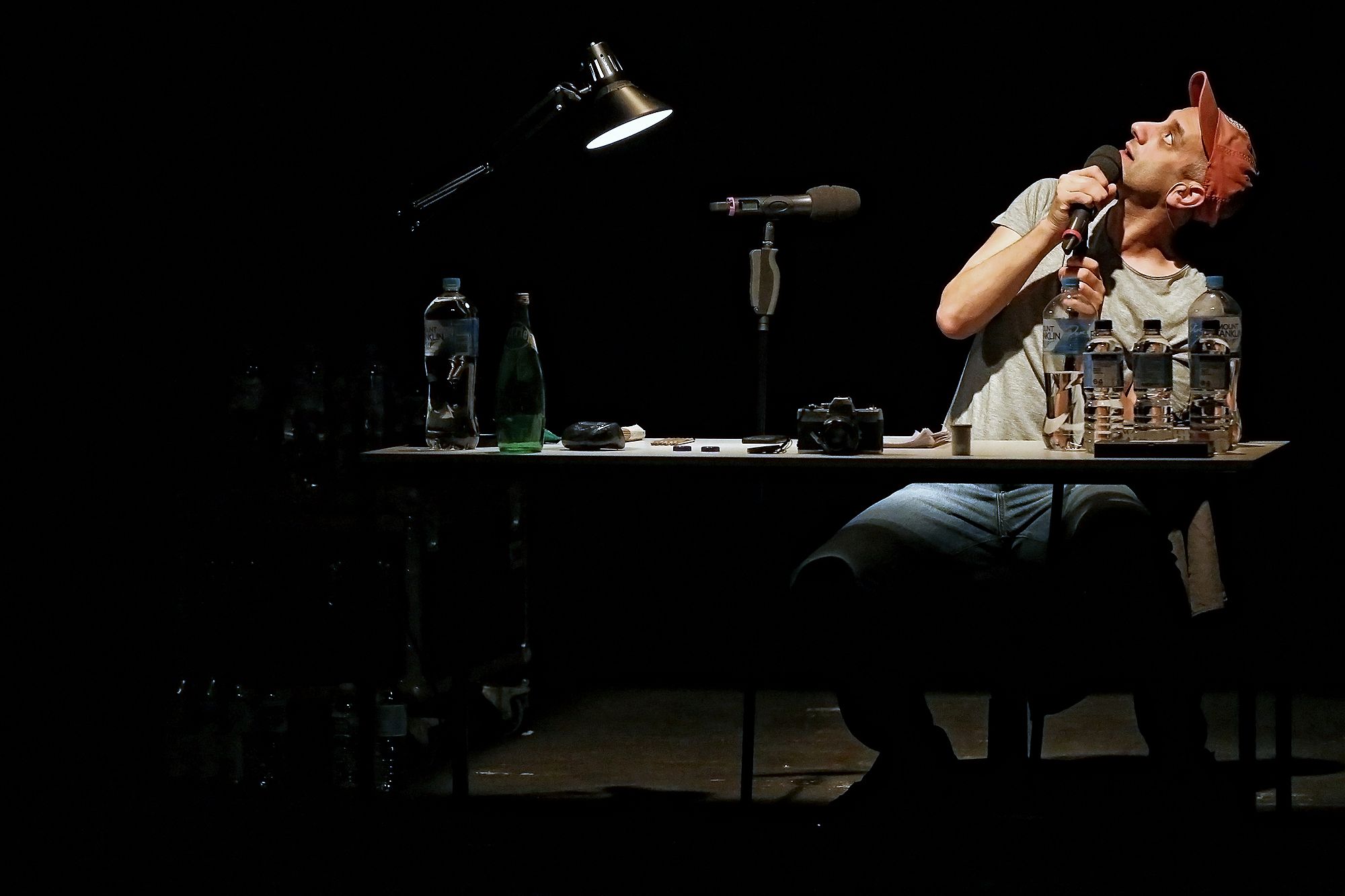

The second time I watch The Encounter, that head is placed on the Drama Theatre stage of the Sydney Opera House as part of the Sydney Festival. New performer Richard Katz, a regular collaborator with Complicite (who will also be the performer in the Auckland Arts Festival) is in Simon McBurney’s role. Katz has been working as McBurney's understudy in the recent Broadway production; the show is in his bones.

The stage is bare but for a basic table and chair, some boxes and crap scattered at the side of the stage and plastic water bottles splayed about the floor. And in the centre, that undeniably humanoid binaural head microphone. The lights are still up and Katz begins to casually chat to us about his iPhone and his kids – a kind of confessional. We then put on our headphones while he slowly introduces us to the technical conventions of the audio technology, and before we know it we’re in a tiny plane flying over the Amazon River. Such is the power of the sound in our imagination, we are physically, palpably in that plane looking above dense rainforest and sitting in a beige velvet chair at the Sydney Opera House.

It’s this seamlessness – not only between storytelling layers, but between content and form – in The Encounter that makes it locked-in-your-seat mesmerising. The story, in part, is about being alone. What is genuine aloneness to us in a Western world and are we ever truly thus? By wearing headphones, the work places its audience in this singular state – among 200 people, but alone – and works with a quality of closeness and proximity in sound that only this technology can offer.

The sound world of The Encounter is an iceberg of technique and artistry. The one performer onstage is balanced by about nine people working on the sound. One person just mixes the microphones.

Through the foil of a photographer – a man whose work depends on fixing his subject and fixing a moment in time – the play also calls into question our fixed notions of language and naming. Do the words we’ve learnt accurately name our external reality? What is this notion of time, really? (Why did I have to watch the live feed of the performance at exactly 8.30am on Wednesday 2 March 2016?) Woven into this theme of the fixity of language, is the possibility of other forms of communication. Loren Mcintyre starts to understand that the Myoruna chief can communicate to him without making sound, in ‘the other’/ancient/non-verbal language. It’s a language he simply hears “on the screen of his mind” just like the intimacy of Richard Katz’s voice through our headphones.

The sound world of The Encounter is an iceberg of technique and artistry. The one performer onstage is balanced by about nine people working on the sound (one person just mixes the microphones) and they work like a team of musicians might. In the earlier stages of performing the piece, McBurney noted “the piece is very much like a piece of jazz, they’re not following the script, they’re following me, because I might do something different – I’m constantly improvising and developing”.

So often ‘the tech’ in theatre is treated as a separate entity – something that runs parallel to the the work to enhance or amplify it. Here it forms the muscles of the work itself: it’s the structure, form and aesthetic, a dramaturgy of sound. McBurney has discussed his dislike for separating out technology and treating video, for example, as a separate tool, when it’s “simply particles of light”. The same goes for the plasticity of sound frequencies in The Encounter. These are vibrations in air. But when placed all around us they unlock our imagination to almost ‘see’ the owners of voices onstage. It’s true that just before the second time I watched The Encounter, I had to remind myself whether there was a second actor – a little girl – in it, or not? “I wanted the audience to feel the presence of the absent” McBurney states. Once again, there’s that tightly bound spiral of content and form that forms a sinew of the work.

*

When McBurney was asked whether he could define the work of his company in one sentence, he simply answered “No. I can’t”. The styles, forms and methods employed by Complicite elude easy categorisation by critics and scholars. It’s notable that well-known English devised theatre companies and artists such as Frantic Assembly and Tim Etchells have at times published texts that offer insights into their methods, yet no such publication exists from Complicite. “Critics have tried and failed to define the essence of Complicite,” says Guardian theatre critic Lyn Gardner. The company’s producer and McBurney’s long-time collaborator Judith Dimant relates that McBurney will boggle, “Why are people writing their dissertations about us? What are they writing? I don’t really know what I’m doing here, so how is anybody able to write something down about it?”

Each Complicite project is approached as its own new performance world. Following the company’s ethos of collaboration, this involves the careful and particular selection of people and institutions that inflect the work in their own way. These collisions between knowledge bases and skillsets demand that work methods remain agile and eclectic.

Yet while modes and methods are elusive, it is possible to trace aesthetic and thematic preoccupations threaded through Complicite’s work. One can perceive roots of The Encounter in Complicite’s large-scale 1999 work Mnemonic. This work focused on the nature of memory and oblivion, and its narrative was layered into three stories, one of which included an auto-referential Simon McBurney/director character. This Simon/director opened the show with a prologue that emerged casually as a bridge from ‘real’ world into performance, and for a moment firmly situated the audience where they were: in a theatre. The Mnemonic prologue also included those first important moments of laughter between an audience and performer. The same occurs in The Encounter. One of the central elements of commedia dell'arte are stock phrases of comedic action, called lazzi. They're there to keep things bubbling, keep the audience on board. It could be said that the small comedic connections the performer makes with the audience in both Mnemonic and The Encounter, as informal as they seem, are in fact well-constructed lazzi; both shows still hold the DNA of the company's commedia background.

The visual sense is so often placed at the top of our sensory hierarchy...but sound can be an infinitely more powerful trigger of our memory and imagination.

The sonic texture of performance that’s so prevalent in The Encounter was also being experimented with in Mnemonic, along with the modes through which we understand language and sound. Mnemonic foregrounded the interplay of a whole spectrum of devices: the microphone, the amplified voice, the recorded voice, phone conversations and a singular voice travelling to the audience from the stage in pitch black darkness. Of course, content and form being so intertwined, these devices aren’t just employed for their textural variance alone; both works are concerned with alternative modes of perception and communication from that which is considered objective reality (memory in the case of Mnemonic, and non-verbal language in The Encounter). The sonic textures are designed to mimic the way we might experience those perceptions. The visual sense is so often placed at the top of our sensory hierarchy, but because sound doesn’t have concrete form, because it literally works on and through our body, it can be an infinitely more powerful trigger of our memory and imagination.

Yes, it sticks around, this one. On my YouTube screen in Ngaio and in the Sydney Opera House, not only was I comfortably disorientated in the present – turning my head towards doors that weren't there and seeing the ghosts of bodies through sound onstage – but when the performance was in my past, I still couldn’t shake the questions The Encounter unearths like thick jungle roots twisting beneath our ‘civilised’ lives. McBurney knows this about the theatre he makes. “Unlike television, which I would call a dilute experience”, he says, “theatre is concentrated. Therefore it continues somehow to operate on you the further away you get from it. It continues to infect you”.

So here’s that theatre evangelist again: see The Encounter. Yes, it’s a groundbreaking piece of contemporary theatre from one of the most important theatre companies in the Western world. It is also one of the most gripping, astounding pieces of art you’re likely to see on stage in a long time.

The Encounter runs from 15 – 19 March as part of Auckland Arts Festival

Tickets are available here.