Committed Passion: Handweavers Guilds and a New Generation of Makers in New Zealand

Jane Ruck-Doyle speaks to makers of all generations to understand the allure of handmade cloth.

Jane Ruck-Doyle speaks to makers of all generations to understand the allure of handmade cloth.

On encountering an Auckland Handweavers Guild monthly meeting for the first time, it was impossible not to be impressed by the evident industrious productivity of a closely-seated group of white-haired women. Almost all were facing the book-lined side of a long room where the chairwoman was waiting to start, and most held yarn and knitting needles for making intricately patterned garments.

I had gone to the Guild rooms in Mount Eden on a sunny Thursday morning late last year to hear Areez Katki, an elegantly creative and dedicated artist and maker in his mid-20s, give a heartfelt talk about his evolving knitting practice – or, as he put it in an Instagram post, “to discuss how the fabrication of handmade textiles enriches our lives”. Areez was first introduced to the Guild members as being a friend of Christopher Duncan, an increasingly well recognised contemporary weaver, who had been another guest of the group earlier in the year. One of the only other young attendees was Winnie Edgar-Booty, a recent graduate from Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Arts, whose final Honours exhibition featured an exploration of knitting as both visual language and social practice.

It was readily apparent to me that there was a strong awareness of contrasting approaches that might be taken to the processes and outcomes of handcraft making, regardless of generation...

Intrigued by the evident passion, or indeed obsession, for handcrafts enthusiastically shared by both generations, I arranged to meet with these younger makers and some Guild members to discuss how they saw their practices in relation to the Guild. It was readily apparent to me that there was a strong awareness of contrasting approaches that might be taken to the processes and outcomes of handcraft making, regardless of generation – particularly around the degree of emphasis put on creative ideas or meticulous technique. It was interesting to consider the possibilities of juxtapositions between practices informed by contemporary art – with their emphasis on fluidity of approaches to expressing ideas and a multiplicity of references to personal, social, historical and cultural contexts, and those of the Guild as a group of predominantly older women who have created, protected and shared an extraordinary repository of handcrafting knowledge, especially technical aspects, over decades.

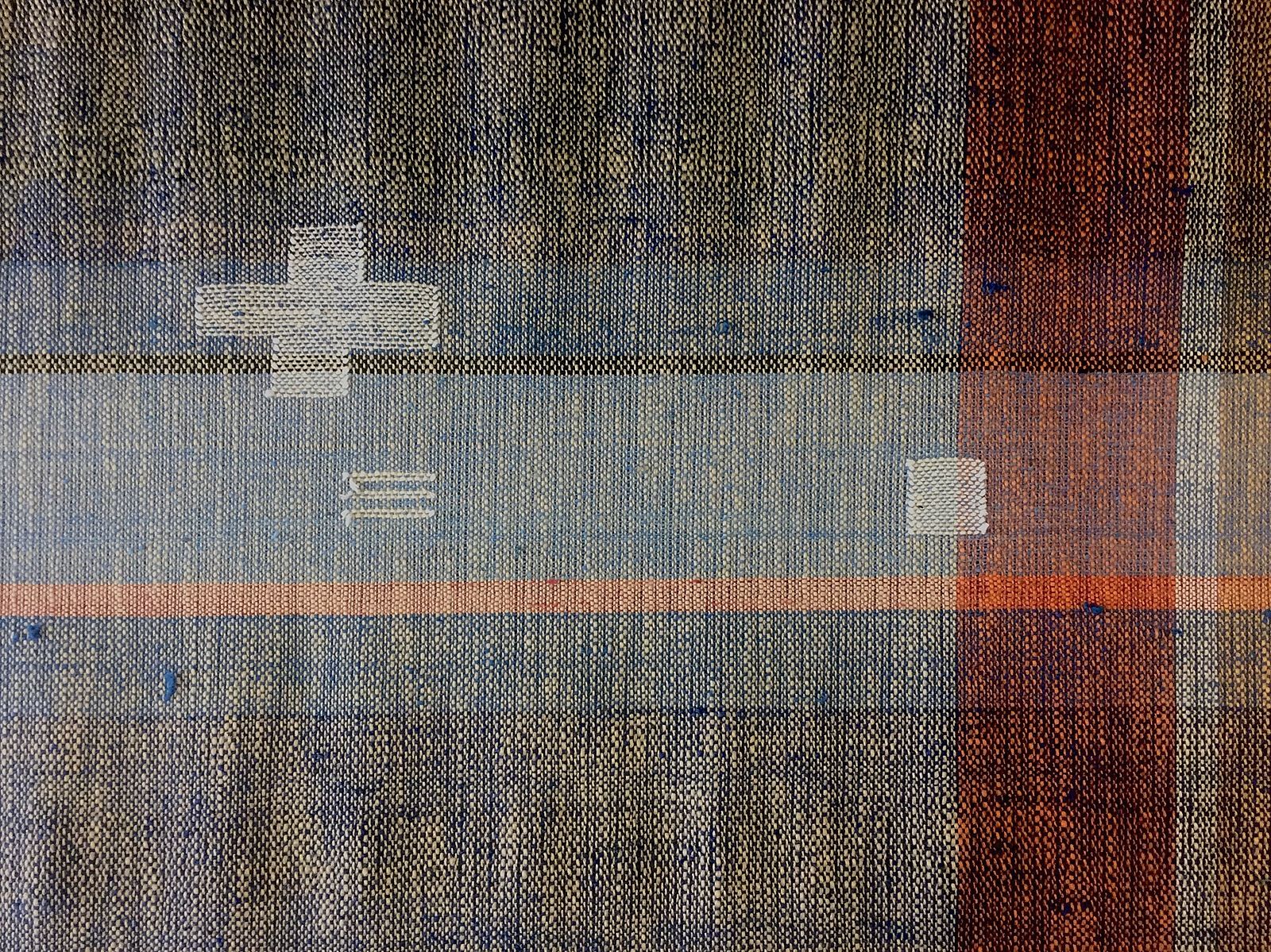

These are issues very thoughtfully considered by Wellington-based contemporary artist Annie Mackenzie, whose practice centres on hand-loomed cloth she weaves herself. The pieces Annie creates are imbued with a high level of creative knowledge, in part acquired through studying sculpture at Ilam School of Fine Arts in Christchurch during the late 2000s, and finesse achieved through dedicated learning of advanced traditional techniques from older members of the Wellington guilds she has belonged to for the past 5 years. Although modest about her skills, she is highly regarded for her expertise and was the 2016 recipient of the national Creative Fibre New Weavers Award. Her work is increasingly exhibited in solo and group contemporary art exhibitions featuring handcrafted objects. Annie has recently made a fascinating series of finely woven tea towels that have been displayed simply hung over purpose-built metal or wooden rails or pinned to the wall. These skilfully made pieces reveal close attention to detail, and deliberately mimic mass-produced cloths that are highly familiar – ones found in packets of three held together with a plastic tie and sold for a few dollars. These cheap and useful items have textured stripes to evoke the appearance of traditionally woven cloth – through remaking them by hand, Annie draws heightened attention to everyday objects and both reclaims and highlights the artistic and cultural value of the handmade.

Upholding an authentic passion for their practices is clearly extremely valuable to all the handcraft makers I met with, regardless of age or level of experience. The younger makers all mention an aversion to apathy that they see as being an unwelcome feature of their generation. On the other hand, many older women, most now in their 70s and 80s, have strong feelings about ongoing connections with the heyday of the 1970s when thriving guilds and groups engaged in making, exhibiting, competing and selling their ‘home crafts’ and had thousands of very active enthusiastic members across the country.

The younger makers all mention an aversion to apathy that they see as being an unwelcome feature of their generation

Generational differences in choices of materials used and the type of objects favoured are perhaps inevitable given shifts in taste for colours and form. Changes in the varieties of materials available, and their qualities and quantities, have influenced what is made and the methods employed throughout human history. Younger makers informed by art practices explicitly say they focus on ‘truth to materials’ and readily experiment with how ideas might be expressed. They carefully select yarns for qualities of colour and hue, feel or strength, particularly those of natural fibres of cotton, linen, wool and silk, sourced from around New Zealand and internationally. Many yarns and fabrics are now available from online sites, but inspiring materials are equally gifted, repurposed or found unexpectedly – such as a bundle of local handspun undyed wool found in a Whangarei Op Shop by Winnie, or for Chris, a one-off discovery of beautiful old Japanese weaving threads to be carefully repurposed.

It seems this is a considerable contrast from handcrafting in New Zealand from the 1960s to early 1980s when spinners, weavers and knitters almost exclusively used and experimented with readily sourced local wool. Import restrictions and tariffs meant that other fibres and yarns such as cotton, silk and linen were very expensive and scarce.

Areez, Chris, Annie and Winnie all mention travel and their experience of very old cultures with deep histories of making and using textiles that inspired them to have a go themselves

It is not surprising that Guild members who remember those restrictions now relish the variety of yarns available online and the fun of experimenting with what can be done with them. Spun wool could be quite scratchy and difficult to care for, while yarns currently available from all over the world are lighter and softer to work with and the vibrancy and variety of colours and novelty of new materials offers appeal. The Auckland Guild also stores an enormous stash of various yarns and materials gifted to them, usually from the estates of makers who have accumulated them over years and years for personal use. The economic reforms of the 1980s resulted in the eventual closure of large scale mills and many manufacturing, and wool fleece is now almost entirely sent offshore for processing. Very limited amounts of local wool are now spun in New Zealand by boutique businesses or dedicated individuals who source fleeces such as Merino, Romney or alpaca.

Areez favours the use of natural fibres and customised vegetable dyes for more complex and often gentler colours. When he mentioned in his talk to the Auckland Guild that he had been successfully experimenting with turmeric root, the older women expressed concern about the instability of natural dyes based on long experience – vegetable dyes were popular and experimented with extensively by many spinners during the 1970s including using local lichens. Fading is now perhaps not just tolerated but welcomed by many younger contemporary makers as irregularity of colour is more evocative of the handmade and human touch, in contrast to the mass-produced uniformity of commercial synthetic dyes & their associated toxicities.

Each of the younger makers I met with articulately described their fascination with ancestry and their personal connections to the depth of history of handcrafting. Areez, Chris, Annie and Winnie all mention travel and their experience of very old cultures with deep histories of making and using textiles that inspired them to have a go themselves. Areez’s Persian Indian ancestry and travels in Spain, Portugal, Turkey and India inspire him visually and culturally, deeply informing his expressive output. Chris has travelled in Taiwan and Japan with his Taiwanese partner and has been greatly inspired by the attention to quiet detail and qualities of ancient cloth. Annie has recently exhibited her family tree alongside her work in a recent exhibition at Enjoy Gallery in Wellington, in order to highlight family members who were weavers or involved professionally with textiles. She was drawn to engage with weaving herself after travelling in Laos and observing age-old creative traditions still in action.

Grandmothers are frequently mentioned by handcraft makers with affection and gratitude as fundamental inspiration for their interest and for initial tuition – observing and learning to knit alongside them and hearing stories

Winnie became fascinated with local knitting creative practices in Iceland while travelling and working there. She carried a set of knitting needles and yarn with her in her backpack to knit wherever she went after staying with her grandmother in North Wales and being absorbed by the possibilities of knitting in expressing social and cultural connections. For her Honours project she spent several weeks completely absorbed in knitting an exquisite square of softest fine lace from ‘cobweb’ wool she ordered from the Shetland Islands. From research into the history of knitting in Great Britain, Winnie was intrigued to discover that she was taught to hold her needles elegantly like a pencil, as done by Victorian women who met to knit in parlours over afternoon tea. An alternative method is to hold needles in the palm of her hand, which is faster and more efficient for utilitarian purposes – a method likely used in the villages of North Wales during the 1800s when both women and men were noted to knit even while walking in order to to produce vast quantities of hand-knitted stockings to meet demand.

Many Guild members have remarkable knowledge of the depth of history of handcrafting and great appreciation for the importance of knowledge being documented, preserved and, most importantly, passed on, so skills are shared and not lost. Grandmothers are frequently mentioned by handcraft makers with affection and gratitude as fundamental inspiration for their interest and for initial tuition – observing and learning to knit alongside them and hearing stories. Areez shared with the Guild a favourite beautiful, very soft cream Aran-patterned sweater that was handknitted while alongside his grandmother. He described the sense of love and warmth entwined in it, and the continued inspiration this gives him for making other knitted garments to sell. The physical warmth imparted by a thick wool sweater and the skilled knowledge revealed in its making intrigued the group. They were especially fascinated by the seeming incongruity of such a warm garment having been created by a woman who was raised and lived most of her life in the hot climate of India.

Learning from other, more experienced makers has throughout history been a fundamental means of transmitting skills to future generations

It seems that the time and care taken by grandmothers to share and pass on knowledge means more than can be expressed, especially in the current globalised world of mobility and rapid sharing of information. Learning from other, more experienced makers has throughout history been a fundamental means of transmitting skills to future generations. An enormous change in recent years has been the availability of online tuition through blogs, videos and social media sites so that expert (and not so expert) advice can be rapidly sourced immediately from all over the world. This enormous accumulation of information is seen as valuable and is used by younger makers selectively as a familiar tool, and by older makers as a useful way of expanding connections and accessing interesting ideas and patterns. But all agree that YouTube clips are no substitute for having someone explain in person where you have ‘gone wrong’, or to give specific tips to make equipment and materials come together more effectively, with more rewarding outcomes. Books are still greatly valued as a resource for visual inspiration and technique. The Auckland Handweavers Guild has an extraordinary library amassed since it was founded in the late 1960s, and even has a subgroup who looks after it. For Annie, the skills she learns as part of group activities at the Wellington Guild – such as project looms which are passed from member to member sequentially to execute a particular pattern or technique – are invaluable for honing her technique and for giving a sense of pride in group effort and belonging.

Interests that skip a generation and close affinities shared by grandparents and their grandchildren are not a new phenomenon, but it is widely commented on that there is a gap in involvement with handcraft in New Zealand by women currently in their 40s and 50s. With further enquiry and research, and reflections on personal experience, it becomes apparent that this is largely due to economic reforms by the Fourth Labour Government of the 1980s. ‘Rogernomics’, with its emphasis on capitalist values and corporate restructurings that favoured profit-driven enterprises, meant full-time work for both men and women that left minimal extra time to learn or practice a craft. Pursuits associated with domesticity or inefficient use of time were no longer valued. In stark contrast to women in the 1970s – who were inspired by women’s movements to find means of making money from their own enterprises at home and as collectives, including making and selling handcrafted objects and garments – the explicit message sent to young women in the 1980s was ‘women can do anything’ in pursuing career ambitions. Maintaining home-based activities or working part-time were not viewed as fulfilling either social or economic potential. In the same period, import restrictions were lifted and protection for New Zealand products was removed, resulting in a rapid and massive influx of mass-produced goods from around the world. This particularly impacted on the production of garments as cheap, readymade clothing became widely available and handmade items were no longer seen as either economically viable or desirable – the ‘homespun’ look was no longer fashionable with 1980s design favouring a certain machine-made gloss. Time efficiencies became a major factor in what was available. Easily cared for items were welcomed. Mass-produced handcraft kits for knitting, embroidery and tapestry became available for hobbyists – if they had the time.

...the ‘homespun’ look was no longer fashionable with 1980s design favouring a certain machine-made gloss

In a heartfelt reaction against these shifts, many women who had the handcraft ‘bug’ continued to pursue their commitment through solitary making in improvised studios, through groups that met in homes, or through ongoing association with formal groups such as guilds. However, a very rapid fall-off in membership to the guilds occurred throughout New Zealand in the 1980s and 1990s and many members who remained felt they had been relegated to the wilderness in terms of recognition. Sheer determination has ensured the survival of these groups. Emphasis on skilled technique also fell away in technical institutes teaching crafts during this period with a shift to favouring looser self-expression and, conversely, more sophisticated design. Night classes were widely discontinued. Finding means to preserve skills at risk of being lost if not taught to others became an ongoing preoccupation and struggle for many – and perhaps a source of disillusionment around observed societal values in recent decades. The ongoing support and social contact with like-minded makers offered by guilds became very important. The current global revival of interest in traditional handcrafts, particularly by younger serious and dedicated makers, and like-mindedness in antipathy towards the banality of mass-produced items and impersonal aspects of corporate capitalist practices, is clearly very exciting and encouraging for guild members.

An inherent value reflected in handcrafting is the slower and more considered use of time. All of the makers I have talked with describe the almost addictive state of ‘flow’ arising from being sufficiently proficient that it is possible to be completely in tune with the creative process at hand and lose all sense of time passing. Chris describes the entrancing concept and sensation of fibres and yarn passing through his fingers many times over with the cloth that is gradually created from interconnected threads being truly made by hand. For cloth weavers like Chris and Annie, this looser expressive creativity typically applies to the weft or side-to-side threads – the initial stringing up of the loom and winding on the fixed warp requires very careful focused technique acquired and practised many times over to get it right.

Generational differences are clearly reflected in the aptitude younger handcraft makers have for authentic self-marketing and the fluidity of approaches they take to sharing their work with public audiences and customers. Areez is particularly adept at using social media effectively to convey a sense of his own personality, connections, and the values he brings to the things he makes – and to reach customers for the bespoke items he sells from his studio and in collaboration with others. Chris uses social media, particularly Instagram, to create awareness of the location of his atelier, TÜR on Karangahape Road in Auckland, and to share details of new pieces. Annie intentionally does not use the internet (other than communicating by email) as she regards it as inauthentic to who she is as a person. She has a dedicated studio space in Wellington and, along with her ceramicist partner, is an active member of various art communities. Winnie says she is currently enjoying making without an audience in her small studio at home while she explores ways of creatively establishing her knitting practice in order to share it with others.

...regular meetings include a ‘show and tell’ session where members reveal their latest production in knitting, weaving, spinning or felting and, as might be expected of any group engaged with skilled activity, a sense of competitiveness creeps in

For older women, self-marketing does not come naturally and for many was actively discouraged in their youth, when one risked seeming ‘up yourself’. Rather, the degree of hard work put in, the aptitude or competence displayed, the quality of the process of making, and the finished product are regarded as speaking for themselves. Self-critique and constructive critique of the work of others is an intrinsic part of the Guild – regular meetings include a ‘show and tell’ session where members reveal their latest production in knitting, weaving, spinning or felting and, as might be expected of any group engaged with skilled activity, a sense of competitiveness creeps in.

For all dedicated handcraft makers, studio space in which to explore ideas, to leave work set up and to store equipment and materials is considered to be vital. With high demand for accommodation and rising rental costs in New Zealand cities there is increasingly limited availability of suitable spaces with appropriate light and spaciousness. This is becoming an issue for the guilds as council rental agreements expire or spaces are taken over for development. Concern is exacerbated by the advancing age of the majority of guild members, leaving a core group of younger members to carry out essential administrative aspects. Knitting and spinning are quite portable and tend to be more sociable activities readily carried out as a group as equipment is easy to take places to teach and share with others, while weaving requires more individual commitment in needing space for a loom to be set up in a fixed location and tends to be more solitary. Space and means for sharing with others, including ideas and skills, is of high concern in ensuring the ongoing functioning of these groups.

A deep sense of human contact is intrinsic to the making of textiles, especially cloth that envelops the body throughout life and which is imbued with human touch, along with a deep desire to share knowledge and experiences of connection

All handcraft makers have stories to tell. A deep sense of human contact is intrinsic to the making of textiles, especially cloth that envelops the body throughout life and which is imbued with human touch, along with a deep desire to share knowledge and experiences of connection. The makers I have recently encountered who have associations with handcraft guilds, whether long-standing or tentative, have clear core values they wish to sustain – of sharing ideas and knowledge, encouraging skills and technique in order to foster creative mastery, providing community, and maintaining the opportunity for others to be equally enthralled by the emergence of a new piece of cloth from carefully entwined threads passing through fingers.

With sincere admiration and thanks to Areez Katki, Winnie Edgar-Booty, Chris Duncan and Annie Mackenzie, who with kindness, integrity and trust shared their thoughts and impressions, and their passion for handcraft making over coffee or delicious tea.

Especially thank you to Alison Francis, a highly experienced and talented weaver who has been a dedicated member of the Auckland Handweavers Guild for more than 30 years and who showed me her well-loved home studio space and loom and shared much wisdom and valuable insight.

Header image: Annie Mackenzie, Elspeth, 2016. Handwoven linen. Photographed by Sam Hartnett, image courtesy the artist.