Cold Reading

Part of an irregular series where one of the three of us will share interesting and frequently extraordinary articles we’ve found on the Internet (Rosabel also posted all the good articles here, two months ago). Huddle in and read up, all!

The Limits Of Fuck You by Chris Ott | Shallow Rewards (June 2011)

You can find an okay piece on who Odd Future Wolf Gang Kill Them All (aka: Oh Fuck Will God Kill These Animals) are via a Google search - be told why they’re so important, get a potted guide on exactly where to delve into their blunted discography, learn the ‘truth’ about their absent and most dexterous voice, Earl Sweatshirt - but then you should take it in the light of this well-annotated thinkpiece. Partly because blogging’s not a paying gig, with the expansive but empty thesis statements a paycheck tends to draw out of music scribes, and almost certainly because Ott doesn’t feel like claiming the last word on this anyway, it’s high on food for thought rather than stone-cold conclusions. The idea he raises are meaty, however: why a middle-class and overwhelmingly white press love the group; how Tyler’s All-Capital State Of The Id Tweets can be tied back to German ethno-linguistic traits; and the gap between the group’s most outré performative aspects and their nominal frontman’s clean living, making a good case for why the notion that these young men are just “kidding around” (often argued by their ardent defenders, even) gives them a pressing use-by date:

One of Tyler’s oft-noted decrees is that he doesn’t “need” alcohol or drugs, which I find really irritating, because it makes Odd Future a Spike Jonze set piece: sick skating, great production, lots of fucking around, but nobody really gets hurt. Surely the group struggles with this, not least because so many rap stars are loud drunks and face-on drug-abusers, but also for Odd Future’s love of skating and skate video culture. On their boards, they are ecstatic children, but outside that Eden, confronted with pop culture’s myriad harpies, they hide behind a questionable, illiquid courage (do it in front of a video camera and you strike out, dude).

What Is Poetry? And Does It Pay? by Jake Silverstein | Harpers (August 2002)

A couple of years old, yup - and as the author himself admits, other outlets from The Guardian to 20/20 had done exposés on dubious ‘international’ poetry competitions, where earnest amateur scribes are lured by the possibility of a published work to spend hundreds of dollars on a weekend at a fading convention centre in Reno (or Vegas, or Atlantic City). Silverstein’s masterstroke is to go into it with relative goodwill, an actual need for prize money, a bevy of historical trivia, and a real poem (‘New York, so often recorded in photographs’). He joins grizzled Vietnam vets, D-list actors, and melodramatic teenage girls in embracing the weirdness of the two days and nights, where others might have retired to a hotel room to gloat into their word processors. It builds to a ridiculous, strangely moving, and totally unforgettable conclusion.

We took a dinner break after the first round of readings, and I considered the field. About half of the Class Six poems suggested that poetry was an instructive art, a pleasant way of passing along an uplifting lesson. In this they fit the neoclassical mode outlined by Sir Philip Sidney in his 1580–81 Defence of Poesie, which defined poetry as “a speaking Picture, with this end to teach and delight.” There was “An Imperfect World,” by Anita Jones of Cincinnati, which put forth, in list fashion, all of the things that were wrong with the world, that we might learn to accept them; “Taking Time,” by Lydia Heiges of Kempner, Texas (she of the glittery dress), which reminded the reader to slow down and enjoy life; “At a Time Like This,” by Myra Ann Richardson of Kernersville, North Carolina, a patriotic verse that aimed to rally our spirits; and “I Want to Know Please,” by Lou Howard of Azle, Texas, which used the device of an inquisitive child to illustrate how “it takes both sunshine and rain to make rainbows.” These poems relied on poetic tropes—flowers that stood for hope, sunsets that led to contemplation—and standard formats—the list, the apostrophe, the regular metrical line—to convey certain messages to the audience. They would have pleased Sir Philip, who felt that poetry’s purpose was to appeal to those “hard hearted evill men who thinke vertue a schoole name, and know no other good but indulgere genio, and therefore despise the austere admonitions of the Philosopher.” Sir Philip figured these men would swallow the uplifting message of a poem, “ere themselves be aware, as if they tooke a medicine of Cheries.”

It’s Not Just Dominique Strauss-Khan. The IMF Itself Should Be On Trial by Johann Hari | The Independent (June 2011)

A great man in his scathing, febrile twilight got there first with an on-the-game tweet; but Hari runs it to the endline, painting International Monetary Fund chief Dominque Strauss-Khan’s New York indiscretion as the inexorable manifestation of his organisation’s rapacious ideology. DMK has been hailed as some beatific moderate who steered the IMF down a more benevolent route; Hari argues this is a matter of rhetoric rather than action, while offering one of the best primers going on where the Fund hit hardest and nastiest over the past 60 years.

Some people claim that Strauss-Kahn was a “reformer” who changed the IMF after he took over in 2009. Certainly, there was a shift in rhetoric – but detailed study by Dr Daniela Gabor of the University of the West of England has shown that the substance is business-as-usual.

Look, for example, at Hungary. After the 2008 crash, the IMF lauded them for keeping to their original deficit target by slashing public services. The horrified Hungarian people responded by kicking the government out, and choosing a party that promised to make the banks pay for the crisis they had created. They introduced a 0.7 per cent levy on the banks (four times higher than anywhere else). The IMF went crazy. They said this was “highly distortive” for banking activity – unlike the bailouts, of course – and shrieked that it would cause the banks to flee from the country. The IMF shut down their entire Hungary programme to intimidate them.

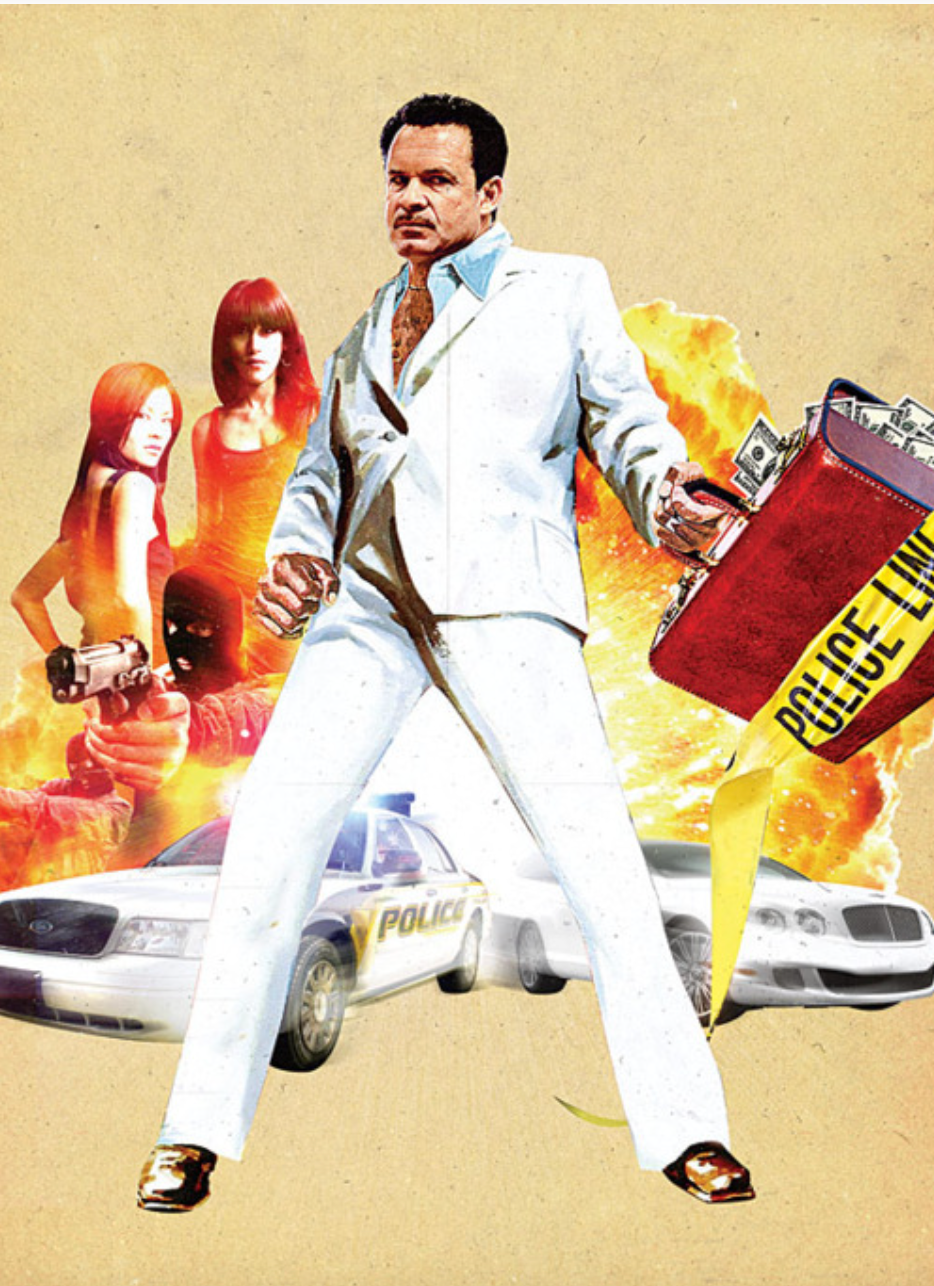

The Baddest Lawyer In The History Of Jersey by Mark Jacobson | New York Magazine (June 2011)

Paul Bergrin was an outlier - an ex-Army family man who went to law school as a mature student, he explosively threw away a glamorous role in the US Attorney’s office to go into criminal defence. He would win fourteen straight homicide cases at a time, while also ardently defending cops who ran afoul of the law themselves. He defended the dumb, confused Jersey boys who were caught out atop a huddle of terrified bodies at Abu-Ghraib, subpoenaed Donald Rumsfeld when he left them to rot.

Methodically, eagerly, he also placed hits on witnesses who would damage his cases - making them look like accidents. His motto: ‘no witness, no case’. A great American undoing.

Back in Jersey, Bergrin’s legend grows. Like Bonnie and Clyde, the roster of crimes he supposedly committed, cases he fixed, expands by the day. His name has turned up in the lyrics of East Orange rappers.

“He’s a local legend,” said one Essex prosecutor. “Paul was made for this place. He might have done terrible things, but it was Essex that helped him get away with it. Face it, criminals have been running things here for a hundred years. When you walk into a courtroom and a whole row of guys you know are Bloods are sitting in the back row, who is going to testify then? No one believes what the cops say on the stand. They haven’t, really, since the riots. If there was ever a place for which the phrase ‘It is what it is’ was made for, it is Essex.” For all the good intentions, a lot slipped through the cracks, which was just the sort of environment where someone like Paul Bergrin could work out his own particular criminal drama.

A Murder Foretold by David Grann | The New Yorker (April 2011)

I ‘ve saved the best until last. David Grann is the author of one of my favourite pieces of journalism ever, “Trial By Fire” (also in the New Yorker, and described elsewhere as the first thoroughly documented case of the execution of an innocent man under the modern American judicial system). Here, he performs a similar sleight of hand to the one he did there, sucking us into the story as it seems - the initial, official account - and then methodically walking us through the layers beneath. An incredibly complex narrative unfolds with a remarkable amount of restraint. Grann could intimidate us with info-dumps and slightly smug exposition from the outset, because he’s done the research to earn it. But he writes - he relates it - as if he’s learning it all alongside us. What matters is that we understand what happened here, not that he made a scoop.

‘A Murder Foretold’ opens on what seems like innocuous stuff viewed from here - the mysterious death of a respected corporate attorney in Guatemala. Without wanting to offer spoilers, I can tell you it turns into one of the most compelling non-fiction political thrillers I’ve ever read, condensed into a 40-minute read. With more twists than even the most convoluted Hollywood film, the resolution is a jawdropper. On the way, you’ll have come to know a lot more about Guatemala’s history, criminal investigations, and Latin American statesmanship. Essential.

In Guatemala, impunity has created a bewildering swirl of competing stories and rumors, allowing powerful interests not only to cloak history but also to fabricate it. As Francisco Goldman describes in his incisive 2007 book, “The Art of Political Murder,” about the assassination of Bishop Gerardi, the military and its intelligence operators concocted evidence and witnesses to generate endless hypotheses—it was a robbery, it was a crime of passion—in order to conceal the simple truth that they had murdered him. “So much would be made to seem to connect,” Goldman writes.

Guatemalans often cite the proverb “In a country of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.” Fighting his way through the political fog, Rosenberg searched for a motive, stubbornly insisting that, if two people were assassinated, then somebody had a reason to kill them. In notes he kept about the case, he reported that authorities had initially suggested the shootings stemmed from a dispute over a fired factory worker. But, by all accounts, Musa had treated his workers well. Were the police and authorities trying to cover something up, spinning another web of disinformation?