Circling The Drain: Sexist Loos, Unequal Spaces

Soong Phoon on gendered spaces.

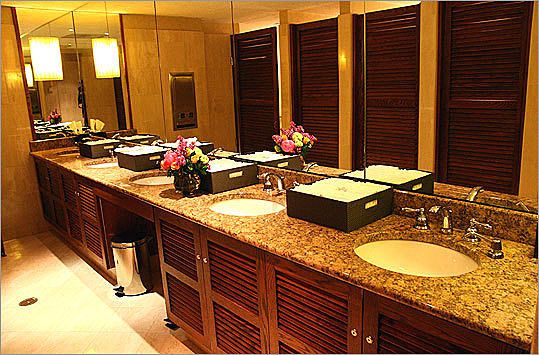

Have you ever had the surreal experience of walking into a ladies' room at an upmarket bistro and momentarily felt that you’ve accidentally returned to the foyer? Or even entered some exclusive, glamorous speakeasy? You’re presented with a shimmering vision of gilded full-length mirrors; flattering, gold-tinted lighting in which to touch up your make-up; even a velvet-upholstered couch (upon visiting the otherwise none too salubrious Mexicali in Newmarket) – and that’s even before you’ve actually considered going to the loo. If you do, you’ll find yourself in an enchanted rumpus room of a stall, replete with further framed mirrors, three-ply toilet paper, and hooks for your handbag.

But should you check out the men's, (only because the women's is occupied of course, not in a prurient way) you stumble upon a forlorn alternative. The sterner sex are only graced with face-sized mirrors, under the fierce glare of bright fluorescent lights which relentlessly expose every line and pore. The misfortune of mere one-by-two meter cubicles for one’s business are “generously” supplemented by rows of urinals.

There hasn’t always been such a disparity - the history of restrooms reveals that everyone once squatted on a level playing field. After millennia of crouching over various vessels or pits dug in the dirt, civilisation progressed; there were constructions specifically designed for one’s excretory needs. Ancient Rome had 952 communal “bathhouses” lined with long benches, upon which people could socialise whilst going about their business. Only a few were gender-segregated. In relatively “modern” times, the very first public water closets (exclusively for male use, by law) were established in 1851 in London.

This legislative history of gendered toilets harks back to the construction of French eateries in the 18th century. As law professor Terry S. Kogan writes for the Michigan Journal of Gender and Law in “Sex-Separation in Public Restrooms: Law, Architecture and Gender”: “the distinction was first established to protect the 'vulnerable bodies' of the weaker sex and provide 'a surrogate home away from home' in the public space.” The States went the same way in 1887, while England lagged far behind in terms of any public facilities for women. Construction of a women’s lavatory in central London was proposed in early 1900, but vehemently opposed by the masculine public. Architectural historian Barbara Penner surmises that the building was considered to actively “sanctio(n)...female presence in the streets, thus violating middle-class decorum and ideals of women as static and domestic.”

The modern zenith of female facilities may’ve seemed like it would’ve ended the matter, but it remains a pressing issue. In recent years, substantial academic research has been conducted in terms of gender separation in restrooms. Kogan’s work queries the problematic scenarios that public toilets present: What happens when wheelchair users require aid from their opposite-sex partner? What kind of disenfranchisement takes place when transgender people can’t utilise the facility of the sex they identify with? What is the dilemma parents face when needing to accompany young children of the opposite sex to the toilet?

Interested to find out if there was an appetite for change among the creators of our public spaces, I spoke to Raphaela Rose, an architecture graduate from the University of Auckland about the aesthetic and physical distinctions between the mens' and womens'. Rose recently completed an award-winning Masters thesis, Sexu(ality) and the City: Counteracting the Cock-ups of Auckland’s Main Strip, which considered the city’s own avidly gendered spaces.

Discussing her research, she describes how Cheshire Architects, responsible for the Britomart Development, consciously designed female toilets in the high-end shopping district to be the “jewels” of the architectural space. She recalls attending a talk by Nat Cheshire himself. What she took from it was that designers deliberately “employed spatial vanity to lure women down the garden path, encouraging the need to appear seductive and alluring, enshrined with these “jewels”.” She cites how he went on to describe “how the area was conceptually constructed and designed for women - an area relating to shopping, food and “nature” with the idea that the men would eventually follow, shopping bags obediently in hand.”

After all, isn't this all women are interested in? Consumerism, clothes, well-groomed greenery and fresh blooms, clothes, gluten-free tapas and clothes? Rose suggests that this is an assumption of “overtly stereotypical femininity and vanity” on the part of male designers like Cheshire – personally, she considers it “a depressing outlook from the supposed future ‘visionary’ of Auckland.” (He’s picked up awards for his various Britomart projects: in 2013, the Herald hailed him as having the potential to transform the grey, glum CBD into a “magical, even poetic city.”)

I discussed this article with two female colleagues as I worked on it. After explaining the argument, one responded: “if there were to be unisex toilets wouldn’t you lose your identity as male or female?” Surprisingly, these traditional gender constructs continue to persist: Mary Anne Case cites the male German response to the end of gender-segregated restrooms and the end of urinals: a reactionary book entitled Die Letzte: Bastion der Maennlichkeit (“Peeing Standing Up: The Last Bastion of Masculinity”).

She also considers relics like the “Bohemian Grove”, an exclusive club (very Skulls and Bones-ish) in California that presidents, corporate magnates and the ilk belong to. They consolidate their solidarity by pissing on the grove of redwood trees outside the club, a feat that prohibits many women. And so, pissing becomes biopolitical: both in a Foucauldian sense - where the physical body itself and its motions are governed by the state - and in the sense that men can transact business deals while utilising urinals alongside each other; a form of networking that women are further excluded from.

While it may seem marginal that the matter of toilets can be viewed as a gender politics issue, it’s recently caused high-profile problems in the US and the UK. State legislatures have come under pressure to pass planning laws that achieve “potty parity”, addressing the unequal provision of facilities, due to space (assumptions that all men piss at a row of urinals, that all women line up outside).

Our problems with restrooms as a society arise from the tension when the private takes place in public. Excretion is a universal experience, but regardless, for most, it’s also a disgusting one. The discourse on toilets invites an exploration into intersexual dynamics: the vestiges of Victorian prudishness about the body; the defined roles of the masculine and feminine. In ‘Coming Out of the Water Closet’, an article from Texas Journal of Women and the Law, Alex More describes how excretory topics “attest to the correlation...of the body and sex to a type of ‘racism’.”

More suggests that the kind of body one inhabits creates its own series of external designations, thereby defining a person’s place in the social and public space. More describes the result as a relegation of transgender people to ‘the leftovers, sexuality’s refuse.” And for plenty of other communities: this is problematic, as there are multitudinous modes of identification that are located along a vast spectrum. It leads us to the discovery that it’s not only the state that governs our bodies, it’s the design of public spaces as well. Architecture itself emerges as a biopolitical superstructure that confines individuals and their capacity to define their own identities.

Rose suggests that gender-specific loos are a historically feminist issue, “a means of controlling gender presence in the public space.” More thorny still is the reality that assigning sexes to architectural spaces perpetuates antiquated gender binaries. Like More, Rose notes the problems in setting a division for those who may not identify as either male or female. Even the signage on a restroom door acts as a mode of architectural exclusion. Genderqueer people are automatically confronted with a sign that precludes them, while those who may identify with a sign will be confronted with further ascribed expectations inside. In Auckland, particularly, heteronormativity and gender norms are inscribed in the structure of buildings themselves.

The argument is that this architectural separation of toilets inscribes and reinforces the belief that men and women are intrinsically different: physiologically, mentally, and emotionally. Japan Air even has specially tailored and euphemistic “Ladies' Elegance Rooms” on their planes. Even in otherwise enlightened areas, it’s the final vestige of sexual segregation that lingers in the public space.

Rose cites the tradition of architecture that continues to entrench these gendered roles: “Historically in architecture, gendered space has manifested in dramatically different ways. Male space is out there in the public realm - take the Northern Club on Princes Street: the male's toilet sits proudly on the external corner, festooned in ivy, whereas female spaces have typically been in the interior of a location”. At some bars, you’ll even find a row of men’s urinals proudly festooned in the open-air behind the bar itself. Apparently women require the additional protective fortress.

The idea of the sanctuary, a combination of chivalry and prudishness, extends to the idea that "the ladies’" needs to serve as some kind of emotional retreat. But is this unique? Doen't everybody use this space this way? And if so, don’t they deserve the same “comforts”? Functionally speaking, Rose argues that “a more streamlined plan in male bathrooms is based purely on the fact that male urinals take up less space and therefore can be compacted into a smaller area. However, this should not be sacrificed for the quality of the space.”

The antediluvian notion of “separate spheres” required to protect the gentler sex is one that’s endured to the present day, a point at which the architectural design of these spaces now actively encourages women to objectify themselves, to reinforce the fact that they must look copacetic on their date/drinks/dinner while men try not to get too much piss on their own shoes then run a hand through their hair.

But there are toilets, and then there are restrooms. Even with these euphemisms, it’s a space it’s often poor-form to chat about over dinner. But when you move from the public loo to upscale establishments, the bathroom space is often a mark of the prestige a bar or restaurant may aspire towards: a part of the experience that won’t usually find its way into the review, but will certainly affect its grade.

“It is often said in the architectural world that you can judge a facility on the quality of its bathrooms,” Rose says. “However, the assumption is that it should go across male and female toilets alike. Consequently, it becomes a given that the lavish quality of bathrooms will most likely be dependent on the decadence of the restaurant or eatery they are associated with, and resultantly this may no longer be operating as a feminist issue but rather a consequence of the contemporary architectural style.”

The fetishisation of an area that has one very basic, crude biological function does seem slightly excessive. Is this really the key to equality in terms of toilets – skyhigh opulence for everyone, with someone to take your coat, dust your shoulders and dry your hands? Returning to deeply lodged stereotypes, which Rose argues are still at play, are notions that “women need a place to “powder one's nose” or “change the baby.” But in our contemporary society, the fixity of these roles is no longer relevant. These are things someone identifying as either gender could do today, and that should be taken into account in any toilet layout.” Some establishments do have “family rooms” where these considerations are taken into account, but they aren’t always there when needed.

So perhaps it's the obvious that solves the quandary: unisex or gender-neutral restrooms, clean and functional, simply utilised the way we utilise our bathrooms at home. Rose agrees, and argues that “unisex toilets are the way forward for architecture today. Gender no longer operates in a heteronormative way and this needs to be reflected in the equality of spaces being provided in facilities. Whether these are then plush or stripped back to a purely functional aesthetic is dependent on the designer.”

This isn’t a far-flung future possibility. Portuguese company Renova prides itself on having established the ‘Sexiest WC on Earth’, in Lisbon, where one can select the colour of one’s toilet paper, and utilise a communal sink. It’s also unisex. Across the Atlantic, gender-neutral restrooms are more common in the States - particularly at universities - after much student advocacy.

Rose concludes that gender-neutral restrooms “most importantly… can't fall into the trap of adhering to conventional forms of masculine and feminine space. I think you'll find that unisex toilets will eventually become the norm. We only have unisex toilets in my own office, and there is something quite refreshing about a chance encounter with a male colleague on a bathroom break.”

As I spoke to her, we each noted the concern of verbal and sexual harassment in restrooms, but agreed it was a mistake to assume that these are sacrosanct spaces where bad attitudes are somehow encouraged or endorsed: these can take place anywhere, and separate bathrooms haven’t resolved this so far. More writes that this assumption “contributes to cultural assumptions about the predatory nature of masculinity and the docile, victimised nature of women.” And Case notes that the notion of the ladies’ as being “safe” is specious, particularly for queer or transgender people. Unisex bathrooms are actually safer, as the possibility of gender or sex-based advantage (and therefore, intimidation) is reduced. A cry for help is more likely to be responded to if it’s a gender-neutral space - anyone might respond to anyone else's cry for help.

It became clear as I worked on this article that Auckland’s standard of public facilities lags behind anachronistically. So while we await further construction of gender-neutral toilets here, perhaps it is our duty to combat urinary segregation, come out of our separate water closets, and own our own attitudes toward gendered spaces. Perhaps sharing toilets proffers as an equalizer. As More states, “unisex bathrooms force everyone to recognise our common ground, the abject component of us all”; our human waste.

Note: This version of the article has been edited for language that caused people hurt and offence. We sincerely apologise for our thoughtlessness in doing this - beyond that, we recognise the need to address issues that this essay only touched upon. An article next week will expand on these issues.