Circling Back

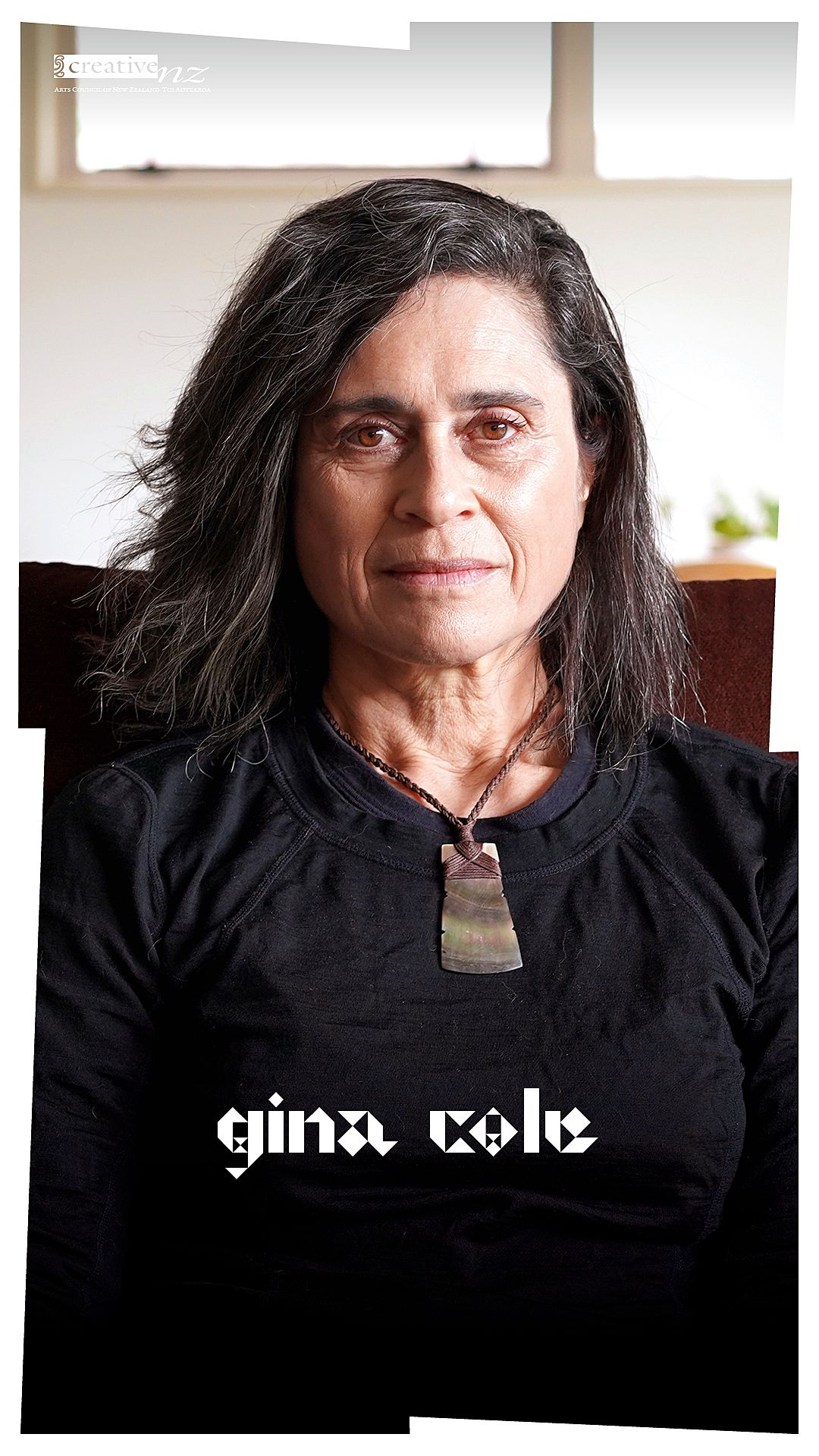

Lawyer and writer Gina Cole on endless cycles, and always orbiting back on ourselves like planets weaving and wending through the cosmos.

We’re collaborating with Creative New Zealand to bring you the groundbreaking Pacific Arts Legacy Project. Curated by Lana Lopesi as project Editor-in-Chief, it’s a foundational history of Pacific arts in Aotearoa as told from the perspective of the artists who were there.

TW: Domestic Violence

It starts where it always does – with the tupuna, the ancestors, stars orbiting through the cosmos. Specifically, my Fijian grandfather, Tua Nacanieli Vunibola from Ono-i-lau, and my Fijian grandmothers. I have many grandmothers – Bubu Keleni and all her sisters from Serua; Pu Veniana and all her sisters from Lau and Tonga, all weavers. My grandfather was the mata ni vanua – the chiefs’ spokesperson. Children would scatter when he arrived. Here comes the lawyer. He spoke with heart, with authority, with mana. He questioned.

Tua always listened to my grandmothers. And my parents always listened to Tua. In 1957 my father visited his father, the Welsh grandfather I never met, in Suva, where he was working as an engineer. There my father met and fell in love with my mother – a beauty queen – third place in the Miss Hibiscus Festival 1957. She went on to star in the movie Two Men of Fiji.

Miss Hibiscus Festival, Suva, Fiji, 1957

The Catholic Church frowned on my parents’ union and refused to marry them. The ‘colour bar’ forbade it. A white British man does not marry an Indigenous Fijian woman. My parents’ view was ‘to hell with the church’. They were young – 25 and 23 years old. Life was an adventure. They defied the bishop and the priest and got married in the Suva registry office. There was much discussion between my grandmothers and Tua when they discovered my parents’ secret marriage. And then Tua spoke.

“For the sake of your children, my grandchildren, for the sake of their education, you cannot stay in Fiji. There is no future for them here. You must go to New Zealand.”

My parents listened and obeyed. Life was not easy for them in 1959 Auckland. Landlords turned them away when they saw my mother. Finally, a wealthy Jewish man leased them one of his properties in Remuera. He told them, “I know what you’re going through.” I tell people I was born in Victoria Avenue, Remuera. Even though I was born in the American army barracks in Cornwall Park. This is not lying – it’s storytelling. I story-tell.

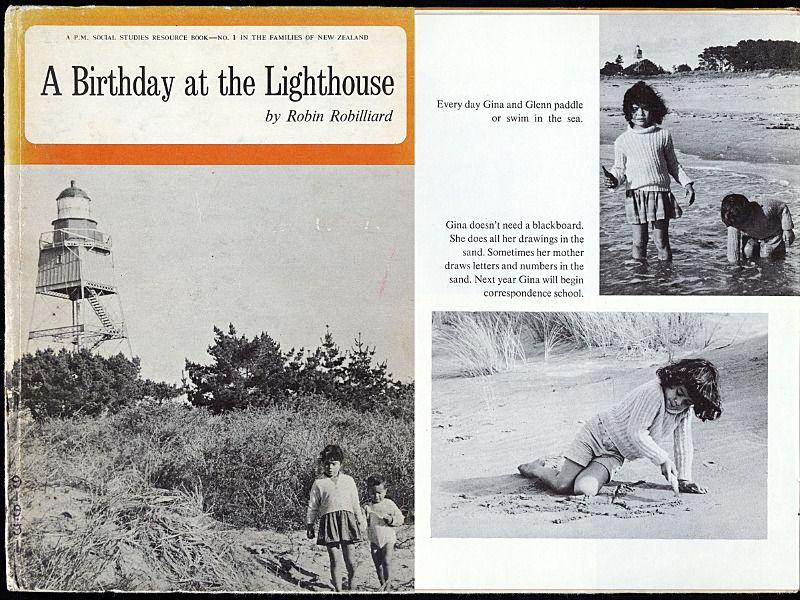

Dad became a lighthouse keeper. His postings sent us to three magical, remote and dramatic coastal locations. First to Te Karaka (Cape Campbell) in Marlborough. Next was Onetahua (Farewell Spit) at the top of Te Waipounamu. Finally, we moved to Te Rerenga Wairua (Cape Reinga) at the top of Te Ika-a-Māui. These isolated and magnificent places still find their way into my writing.

For the sake of your children, my grandchildren, for the sake of their education, you cannot stay in Fiji. There is no future for them here. You must go to New Zealand.

We lived at Farewell Spit until I was five years old. This is where I discovered books and nightmares and horror stories. Dad is an obsessive buyer of books. Boxes of Time Life books and Readers Digest books, classic novels and historical treatises arrived on the supply truck. The Western canon and European history. I leafed through these tomes, poring over the images, trying to make out the shapes of the words and the lines of the letters, and pretending to read.

The all-pervasive rotating light from the lighthouse shone into my bedroom every night. I thought it was a monster. I had recurring nightmares under its mysterious arcing glow. In one horrific episode I sat on my father’s shoulders and a Papua New Guinean tribesman in loincloth and full ceremonial headdress with colourful feathers, and a thin white bone pierced horizontally through his nose, appeared in front of us holding a spear aloft. He threw the spear at my father’s chest. I woke up screaming. I knew this warrior from one of the books I read regularly during the day. An ancestor? Tua told me we have Papuan whakapapa – my great-great-grandmother. In another dream, yet another scene taken from the pages of a book, my mother held my hand as we hurried through the cobbled streets of some European city. A troop of soldiers appeared in long red coats with white turned-over corners, lots of gold buttons, high black hats and long shiny swords. One of the soldiers killed my mother. I woke up screaming. An ancestor? I always woke up crying and screaming from these nightmares. My parents would rush into the room and ask me what I had dreamt. I hated to relive the terrible scenes, but they insisted. So, I would narrate my horrific dream-stories for them.

At Farewell Spit my mother taught me by correspondence school. I learnt to write words with my mother. I drew shapes and letters anywhere, any time, on paper, in the sand, in the earth, on the walls and the floor. A constant connection with the ground, with surfaces, although my parents did not encourage the wall and floor daubing.

I drew shapes and letters anywhere, any time, on paper, in the sand, in the earth, on the walls and the floor.

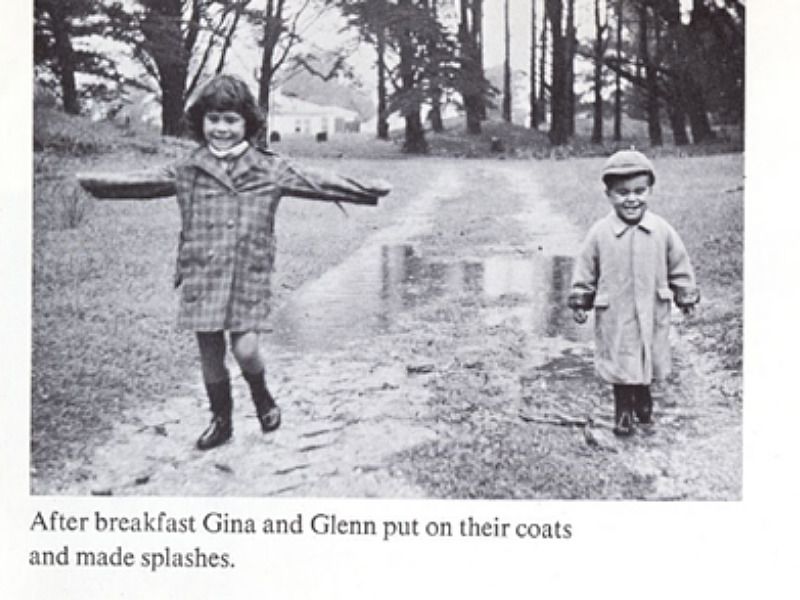

The Listener magazine sent someone to take photos of us. Pictures of me and my brother playing in the rain under the pines, our life at Farewell Spit displayed in broadsheet pages. We held onto a few copies for a while. Robin Robilliard visited and wrote a book about us – A Birthday at the Lighthouse. These treasured artefacts, these books, and words that tried to contain and define us, and writers with melodic names, became part of our family culture, stories we told about ourselves.

*

*

Farewell Spit – Cole and her brother, Cole's Mum on guitar (Photo: Supplied)

For the sake of our education my parents made the decision to move to a big city. Away from the beauty and peace of lighthouse life at the edge of the ocean. The District Nurse decided I had lived too long in isolation from other children (what did she think my three siblings were?). According to her and her bosses I had to learn to socialise with other children. They sent me to a Health Camp for six weeks. When I asked my mother about this recently, she told me that the authorities gave them no choice in the matter. I was five years old. Such a barbaric thing to do to a child of that age. I felt helpless, confused, lonely and homesick. This disease-ridden institution was a prison for children, as far as I was concerned. My fellow child inmates and I contracted chicken pox, which swept through the dormitories like wildfire. I was ahead of the other children in reading and writing so the teacher told me I needn’t attend classes. I did not learn to socialise with other children. I learnt I was an outsider. I free-ranged everywhere with another outsider. Call him Shane. Shane was naughty and we ran amok in the grounds and the buildings. We often found ourselves in the Head Nurse’s office. She always questioned Shane, never me. He told good stories, explained away our exploits, while I remained silent, unsocialised.

Dad became a police officer – we went to Wellington, where he attended the police college at Trentham. Dad hated the paperwork involved in being a policeman, so he stepped down and became a prison officer at Mount Crawford, which came with a house overlooking Wellington Harbour. I attended Miramar Primary School, where a gang of white girls, led by a blonde girl, followed me around the school grounds and chanted ‘Dirty Pierre’ in my face. They had named me after the bad guy in a television cartoon. Dirty Pierre was dark and filthy and monstrous.

Shades of lighthouse life filtered in where we lived, high above Wellington Harbour – one breath from the sea. I played in a forest of pine trees next to our house – another breath from the trees. From our vantage point on the peninsula, we saw the Wahine sinking in 1968. I told people I had seen survivors scrambling onto the side of the boat as it listed. Even though that would have been impossible. This is not lying, just embellishment of the truth, sometimes known as storytelling.

This is not lying, just embellishment of the truth, sometimes known as storytelling.

We moved to Dad’s next job at the brand-new, high-security prison in Paremoremo, Auckland, which came with a house in a small settlement next to the prison. We lived in Hitchcock Crescent. I decided someone had named our street after Alfred Hitchcock, the master of suspense. I loved his movies and the game of trying to spot his appearance as a background extra in each of his films. I attended Paremoremo Primary with all the other prison officers’ kids. On my first day the teacher made me share a desk with a blonde kid. I think this kid sensed my fear of blondes. She teased and bullied me. The teacher watched it happen. I watched the teacher watching it happen. The teacher watched me watching her. The blonde kid was oblivious to the watching. I calculated the time when the teacher’s sympathy towards me was at its peak and made my move, marching to her desk to complain. An orchestrated little charade we had silently agreed would happen. The teacher told the blonde kid to stop it and the girl turned and became my best friend. Kids! It helped that she lived across the road in Hitchcock Crescent. It helped that there was a full set of Encyclopaedia Britannica in her house that we would read together. It also helped that I had stacks of Superman comics that we would read together.

Dad hated the riots in Paremoremo Prison and left the prison service. We moved into Milton Road in Mt Eden. I decided someone had named this road after John Milton and I learnt some of his poetry off by heart. “They also serve who only stand and wait.” Dad moved through a rolling succession of jobs – truck driver, model, bus driver, tour bus driver, pest controller, insurance salesman, sailor. Mum worked too – in the Big Ben pie factory, as a cleaner, a retail assistant, a buyer at Haywrights in St Lukes, then at Farmers. My parents were always working.

By this time, I was a painfully shy, bookish, withdrawn and agoraphobic pre-teen. I found it extremely difficult to even walk down the road to the shop. I didn’t fit anywhere. I wrote fragments in little notebooks and read comics. The shock of seeing domestic violence in my own home, for the first time at the age of 12 years, hit me like a hammer to the heart. My complete inability to process the confusion and helplessness. My reaction turned me overnight from an introverted shy child to an angry, aggressive, rebellious hell girl actively defying and challenging my father at every opportunity. Paying for it by becoming the target of his anger and violence. With no skills at all to deal with what was happening, I became a ball of rage. Trying to stage a suicide attempt that sent me to hospital. I hadn't drunk the Mercurochrome. I just daubed a bit on my lips and lay down on the floor with the bottle in my hand. I don’t know what I hoped to achieve with this desperate Shakespearean performance. I just needed a way out. I paid for it by having my stomach pumped for no reason. The young doctor shaking his head at me. A white man with a beard interviewed me, a social worker or a psychologist or a psychiatrist. There was no way I was going to talk to him. His questions rendered me mute. Couldn’t he understand my narrative? I’m here, I’m sinking, help!

I didn’t fit anywhere. I wrote fragments in little notebooks and read comics.

Somehow, I made it through secondary school, my refuge. The place where people valued me, where we studied and appreciated words, where my reading and writing paid off. I escaped to Fiji on several occasions, where I would hole up and read books non-stop. Tua and the grandmothers anchored me, gave me a place of calm and normality. My family in Fiji surrounded me, they spoke Fijian all the time. Only Tua spoke English. My inability to communicate in Fijian suited my withdrawal. When I wasn’t reading books, I sat watching my grandmothers endlessly weaving ibe (mats), constantly weaving our histories in pandanus storylines.

When I was 19 years old I decided that if I left home, the violence would stop. In the twisted logic of helplessness, I felt I was the cause. I followed a friend to live in Sydney, made some bad decisions. My life turned to low self-esteem, anxiety, loneliness. At one point I felt like I had left my body, that I was hovering overhead, watching myself go through the motions of life, completely detached from myself. I knew something was wrong with me. But I didn’t know what to do about it and I didn’t seek medical help. I realise now I was in a state of deep depression. At the time, all I could think to do was visit Tua and the grandmothers in Fiji. They knew there was something wrong – I heard my grandmother talking quietly to Tua in Fijian every night. I understood bits and pieces of their concerned conversation. One day Tua told me to stop looking down at the ground, to lift my head up and be proud. I hadn’t even realised that I hung my head down all the time. That simple instruction of care and love, the act of holding my head up, unfurling my heart, easing my breath, helped me to change my perspective, my life.

One day Tua told me to stop looking down at the ground, to lift my head up and be proud.

I knew I had to leave Sydney. It was too urban, there was too much concrete in my head. I went back home to Auckland thinking I had done the right thing by leaving. Life would have magically gone back to a peaceful state in my absence. I was so wrong. In my first week back in the family home I got a hiding. I couldn’t believe it. I fled and found a flat next to the university in Symonds Street that reminded me of Sydney. Lots of concrete. I frequented the Globe Tavern across the road and listened to poetry readings by David Eggleton, Michael O’Leary and Bob Orr. I started writing poetry. One night I got up and recited one of my poems. People clapped. I went to clown school and performed street theatre in Queen Street. People clapped. I met Clare O’Leary, Michael’s sister. I joined her postpunk Lesbian feminist band – Vibraslaps. I found myself performing, writing songs, trying to imitate The Cure. I also performed with a Māori and Pasifika women’s band called The Silverbeats. Less Cure and more blues and reggae.

Cole singing with the Vibraslaps and playing her Fender Stratocaster.

Left: Clare, Diane and Cole (Sarni joined later), the Vibraslaps, Right: Cole performing with The Silverbeats in Aotea Square.

A self-described butch lesbian separatist with a black belt in judo pursued me. Maybe predated would be a better word than pursued. I was in no state to be with anyone. I was 23 years old, the same age as my mother when she married my father. Here was someone paying me attention. I went along with it, fell into my first relationship with a woman. It was a mismatch. I went with her on the hīkoi ki Waitangi in 1984 to protest the Waitangi Day celebrations. She drove the bus. I moved into a large house with her and some other Lesbians. I wanted to weave like my grandmother, and took a raranga kete course. I lucked into a job weaving tukutuku panels for the whare whakairo, Tāne-nui-a-Rangi, at Waipapa Marae, the new marae on Auckland University campus. I hung out with the carvers and weavers. We went to parties at the Anthropology Department. I met Pat Hohepa, Ranginui Walker, Meremere Penfold, Margaret Mutu and many others.

Weaving a tukutuku panel at Waipapa Marae

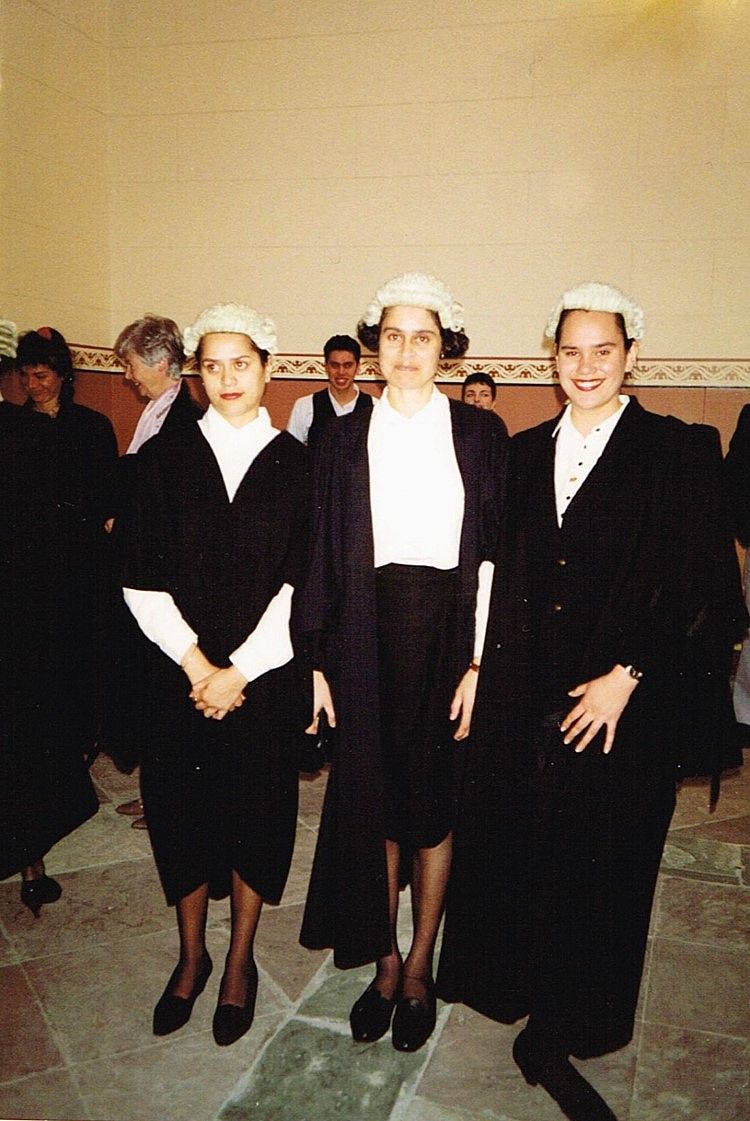

The Māori law students were my favourite group to hang out with, and I became enthralled with one of them. Let’s call him Mānawa. He was smart, outspoken and charismatic. There were endless parties with the Anthropology Department, the carvers and weavers, and the Māori law students. My girlfriend found out I was carrying on with Mānawa. I came home drunk one night from a party. I woke up the next morning with two black eyes. I had no recollection of what had happened to me. One of my flatmates told me she’d heard my girlfriend throwing me around the bedroom like a rag doll. It sickened her. I couldn’t believe this was happening to me again. I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know about protection orders and didn’t report the assault to the police. I had nowhere to go. I fled to my parents’ house. I knew I couldn’t stay there long. Just long enough to heal. I decided to follow Mānawa to law school. He’d dropped out by the time I got there, and I never saw him again. The pōwhiri for the law students took place at Waipapa Marae. I sat under one of the tukutuku panels I had woven, Uenuku, a rainbow atua, and listened to the kōrero. Hana Jackson told us too many Māori were dying, so kill a white. People got up and walked out of the wharenui. I stayed and listened to the stories.

Admission to the bar at Auckland High Court in 1991, me ōku tino hoa Janet and Lope

When I became a lawyer, the first time I took instructions from a woman applying for a protection order against her violent partner, I had to leave the room. In the quiet of an empty office, I burst into tears. The woman’s story triggered my own painful memories. I knew what she was going through. I had to talk to lots of counsellors, and grow a thick skin, to help people in violent situations. To try and protect them. To tell their stories for them.

The first time I visited a client in Paremoremo prison, the concrete monolith that had loomed in my childhood seemed tacky and worn, a zoo for people. The guards always lock lawyers into visiting rooms while they bring the prisoner down from the cells. One time during a code blue at Mt Eden Prison – a riot – the whole place went into lockdown. I waited in the locked cell for hours. I spent the time writing on my legal pad. I wrote about the hard, grey room, a number stamped into the concrete high up on the wall, a piece of cotton thread on the concrete floor. The waiting. I transferred my prison writings to my secret journals. I have courtroom writing too. Some lawyers’ cross examinations go on interminably, for hours, days. Some evidence is dreary and repetitive. At the edges of hyper concentration, you appreciate the quality of light in the room, the swaying trees outside, the hilarious verbal fracas. “Your Honour. My learned friend’s submissions are replete with split infinitive and tautology. We are engaged in endless trench warfare in the interlocutories. This must sound in costs!” Lawyers and their words, their tools of trade.

I had to talk to lots of counsellors, and grow a thick skin, to help people in violent situations. To try and protect them. To tell their stories for them.

The dyke hike went through one of the tracks in the Waitākeres, maybe Goldie’s Bush, or maybe the track through the bush on the other side of the water hole where I used to swim with the eels and do dive bombs in the stream at the back of Hitchcock Crescent. I was walking next to a woman named Jenny Lawn. I told her I was a lawyer, that I had enrolled in Continuing Education writing classes, and I wrote in secret journals. She told me she was the Head of School in the English Department at Massey University, that I should do a Postgraduate Diploma in English. She sent me the prospectus, mapped out the papers I should take, mapped out the whole diploma for me. I enrolled, and completed two papers – Life Writing with Pip Adam and poetry with Johanna Aitchison. When my cousin’s friend Selina Tusitala Marsh heard I was studying at Massey University she told me to apply for the Master of Creative Writing (MCW) at Auckland University. The following year, 2013, I cobbled together a portfolio of my writing from the Massey courses and some of my secret journal fragments. I got into the MCW course. Selina was my supervisor. I lawyered during the day and wrote in the interstices. I wrote a collection of short stories, Black Ice. I sent my manuscript to Huia Publishers. They accepted it. The name changed to Black Ice Matter. It won the Ockham Book Award for Best First Book in 2017.

That same year, 2017, I started a PhD in creative writing at Massey University. Thom Conroy and Tina Makereti were my supervisors. I wanted to draft a novel as part of my thesis. At a te reo class one of my colleagues, a High Court judge, asked me, “Why do you have to do a PhD to write a book? Why don’t you just write it?” Good question. I’ve only authored poems and short stories. I don’t know how to draft a novel. I need structure. My supervisors are novelists. They will help me. My reasons seemed lame. But it worked for me. In 2021 I graduated with a PhD in creative writing. Jenny Lawn was on stage with the other faculty members at my graduation. My book is with the publisher.

Massey University PhD graduation, 2021

And so it goes, with us the mokopuna, and the tupuna, in endless cycles, always orbiting back on ourselves like planets weaving and wending through the cosmos. Tua and Bubu and Pu and all the other tupuna are watching over me. I keep circling back, navigating, wayfinding – we all do. I’m still learning and performing and writing.

*

This piece is published in collaboration with Creative New Zealand as part of the Pacific Arts Legacy Project, an initiative under Creative New Zealand’s Pacific Arts Strategy. Lana Lopesi is Editor-in-Chief of the project.

Series design by Shaun Naufahu, Alt group.

Header photograph Edith Amituanai