Christchurch, and the heart of the Antipodean Gothic

Jasmine Gallagher on the wrong side of a broken city.

I love the great despisers, because they are the great adorers, and arrows of longing for the other shore.

I love those who first do not seek a reason beyond the stars for going down and being sacrifices, but sacrifice themselves to the earth, that the earth of the Superman may hereafter live.

I love him who liveth in order to know, and seeketh to know in order that the Superman may hereafter live. Thus seeketh he his own down-going.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra

I wrote this piece after a stint around 2014 living in Richmond, Christchurch. I had just finished my M.A. and was wondering where to go and what to do next. I have since retreated to Loburn, North Canterbury, after a brief time in Berlin, but I have the fondest memories of a time in Christchurch where certain elements came together: music, people and place. This alchemy occurs every now and then to create a community that those of us who come from smaller cities, and who tend to keep to themselves, don’t always experience. Having a close knit music ‘scene’ isn't exactly unique, but they do wax and wane. And since the demise of All Plastics and pondering the demolition of Pagan House, I think there are certain elements that are worthy of humble documentation[1]. So this is a tribute to those who share fond memories of this brief time – a time that repped the best elements of a music scene, without all the pond-scum blood-sucking shit that inevitably comes along.

So often I get asked by friends who have buggered off to Melbourne, Berlin, New York, etc “how’s Christchurch?” in a sort of pitying tone. I get it. Christchurch can be a bit of a cultural wasteland at the best of times. As New Zealand’s ‘whitest city’, it ‘s clearly dominated by European second-settlers of a certain conservative Victorian heritage and bearing, and this still represses cultural expression to a certain extent. From the hard working farmers and tradies, to the bogans, the sporty, and the practical-minded entrepreneurs, there seems little room for the more purely creative and intellectual world of art and ideas to thrive. Yet, sitting here on the concrete step at the back-door of my flat, on the last section before the red zone and river in Richmond, trying to smoke a cigarette, watching the fantails flit amongst the rotting fruit, I must admit, I really do love this place.

I guess I realised part of the reason why I’m a bit partial to Christchurch when I was completing my M.A. in Sociology last year. I was studying critical theory and New Zealand landscape mythology. This meant offering a critique of the beliefs Pākehā (like myself) have had about the New Zealand landscape, and the way these have dominated the development of a New Zealand ‘national identity’ over time.

Such a topic involved addressing an inherently tricky question: how could those of us with European heritage call this land our home, whilst having a critical realisation of how we came to be here? I found this sense of post-colonial unease reflected in Pākehā landscape mythology. These myths expressed a Romantic and antimodern obsession with empty and pristine New Zealand landscapes, as icons of the organic, the outsider, and isolation. Such myths have been strongly critiqued for two main reasons: firstly, for conveniently glossing over the realities of our post-colonial society, by ignoring the problems of the modern urban life most New Zealanders experience, and secondly, for signifying an unrepresentative lack of local culture (other than depictions of 'traditional' Māori culture, often appropriated and smoothed out for national branding exercises).[2] Despite these critiques, I could also see remnants of these myths persist in a unique and critical form in Christchurch’s urban culture – especially through music.

The music I am going to reference does not ignore the problems of urban New Zealand life by looking to emptiness in a sentimental or therapeutic way. Nor is it ironic, or derivative of Māori or foreign culture. Rather, it focuses on isolation and the organic in a critical way, embracing them as crucial aspects of the creative process, and thus embodying a Romantic turn away from mainstream modern society—as seen in the idea of the outsider.

During my post-thesis stoop pondering, I’ve named this phenomenon the Antipodean Gothic, and, as I began to see this gothic complex in all the things I love about this place, it served as a justification of sorts for the magic this broken city held and holds for me. So here’s my somewhat mythic account (primarily based on personal experience and word of mouth) of the concept, and the people, landscape and soundtrack that make me want to wallow here. I thus declare this fallen but undead city as the capital and centre of the Antipodean Gothic—as a place that allows a sincere reconsideration of the inclusions and exclusions inherent to our cultural imaginings, right here in late-capitalist New Zealand.

I: THE GOTHIC AS THE PERVERSE WHICH FREES US

A Decadent and Romantic fascination with the darker side of life—with the unholy, shadowy, unknown, broken, grisly or decaying—lies at the heart of the gothic. The somewhat contradictory though very human nature of the complex means that there are many definitions of the term. However, I like the way Edmund Burke explained the gothic complex in his 1757 Philosophical Inquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful:

When danger or pain press too nearly, they are incapable of any delight, and are simply terrible, but at certain distances and with certain modifications, they can be, and they are, delightful, as we every day experience.

This quote highlights the tension and contradiction inherent to the gothic stance, leaning on the inherently European baggage of cartesian dualism we still drag around with us through the West: sublime and terrible, light and dark, good and evil, sacred and profane, dead and alive, enlightened and benighted, modern and antimodern, nature and culture, orthodox and heretical.

It also highlights how revelling in the perverse elements of these dichotomies can offer an element of pleasure or freedom, rather than pain. So, because definitions of the gothic inherently rely on a tension between such dichotomies, (usually with one half repressed, rather than removed) one may see how the Antipodean Gothic finds its home in Christchurch, in its button-up European heritage that holds back yet revels in the perverse.

And perversely, New Zealand sits on the opposite side of the globe to the traditional European centres of culture, including its cities and high society. However, the Antipodes has always been more than just a geographical opposite – it has been, and still is, a mythic one. The roots of this fascination with the perverse can be seen in the European mythology that surrounds the place of New Zealand itself (mythology that is still embedded in our urban culture, tied to notions of European Decadence and Romanticism, just as gothic culture is), and it's these associations that still permeate much of New Zealand culture today.

A brief account of this landscape mythology shows how the idea of the Antipodes was, and still is, one of outsiders, as opposed to insiders; of isolation, as opposed to integration; of the antimodern, as opposed to the modern; and especially, one of nature and the organic, as opposed to culture and the reflexively constructed. More importantly, understanding the history of these ideas allows us to see how they have been expressed in various ways, with different effects, over time – from the colonial settling of New Zealand, through the ‘cultural nationalist’ period of the 1930’s[3], to our neoliberal national branding exercises of today.

II: THE ANTIPODES AS THE PERVERSE WE INHABIT

The Romantic reaction to the Industrial Revolution at the end of the eighteenth century in England saw the creation of the Arcadian myth of the rural idyll, as can be seen in the work of William Blake:

And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon England’s mountains green:

And was the holy Lamb of God

On England’s pleasant pastures seen!

Idyllic imaginings of England’s past like this were soon transposed onto the Antipodes—a place which represented the purity of nature, as opposed to the Decadence of an increasingly urbanised fin de siecle European culture. New Zealand’s geographic isolation was particularly eulogised, because it embodied the European idea of antipodean lands as a distant Arcadia.[4]

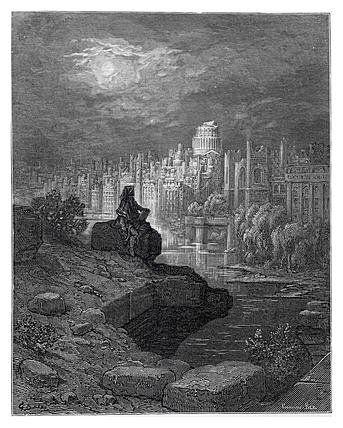

Such mythologising was exemplified in the 1872 engraving by Frenchman Gustave Dore—"The New Zealander"—that pictures an ‘exotic’, nominally Māori, figure contemplating a scene of London in ruins. This imaginary New Zealander was on a sort of death-watch, observing the fall of Western civilisation, from a vantage point from where it was imagined cultural Decadence could be escaped through sheer isolation from the Old World.[5] Such sentimental ideas were exacerbated by the colonial fallacy of regarding antipodean lands, such as New Zealand and Australia, as terrae nullius, which saw the idea of the New Zealander (both Māori and Pākehā alike), come to embody that of the outsider, (rather than that of a socialite or insider, like the elites of Europe).

By the 1930’s, our cultural nationalist artists and intellectuals both identified with and revelled in this idea of the outsider. However, they challenged the idea that New Zealand was free from the problems of modern society, by focusing on the exclusion they felt from within New Zealand, rather than European, culture and society. For this reason the cultural nationalists were referred to as proponents of an ‘anti-myth’[6], because they critiqued the sentimental colonial myth that New Zealand was isolated from the problems of the modern world. Although they still found solace in nature, they took a different look at the New Zealand landscape. They challenged the sentimental colonial myth of New Zealand as an idyllic southern Arcadia, canonising work which painted the New Zealand landscape as a harsh wilderness. Pākehā cultural nationalists thought this place offered a fresh and antimodern perspective on modern civilisation, rather than the sentimental and nostalgic one they associated with the outdated colonial gaze. So, the landscape continued to provide a form of salvation and landscape Romanticism remained, albeit in a different, more critical form, It was a harsh and undifferentiating wilderness, rather than an idyllic Arcadia.

Today, this Romantic, antimodern stance towards nature and the New Zealand landscape remains achingly obvious as a matter of national branding. But although these dominant Eurocentric visions of the nation continue to revel in the perverse of both the nature-culture and inside-outside dichotomies, today this is really only in the hyperreal. Like John Key said in 2012, we don’t actually take the idea of 100% Pure New Zealand seriously anymore. We know it’s not true.[7] We can even see how dangerously close it has come to being a cynical parody (though we continue to permit it).

However, I’d like to suggest that there are still aspects of our culture in New Zealand that accentuate this obsession with isolation, space and the nature of being outsiders in a more sincere and critical way. This is where the Antipodean Gothic complex comes into play, neatly dropping down between the floorboards of the suburban life that props up our 100% Pure cultural façade. This means it requires a bit of local knowhow to find it —the kind that does not rely on the hyperreal imagery of the outdoors and our rural landscape alone. Cue Christchurch city, circa 2014.

III THE PERVERSE MICROCOSM OF THE CHRISTCHURCH LANDSCAPE

The physical and figurative Christchurch landscape has a fair few gothic associations already. Part of this is because the Garden City has always been a bit of a ‘hole’—in more ways than one. I can remember one of my hippy mates once saying that Christchurch had ‘bad energy’ because it was built on a swamp. On cold nights, the smoggy air hangs around, a semi-toxic fume, partly trapped by the Port Hills and hiding from breezy airs in this geographic slump that sits below sea level. Similarly, I’ve heard other people say ‘don’t get trapped in Christchurch’, like it has some sort of slippery sides designed to snag prey from escape, allowing a sort of vampiric drainage to occur to those who don’t manage to scale its walls to the outside world. And now, the city has been partially destroyed, and the earthquakes have acted as a kind of catalyst. The Antipodean Gothic seems to have taken hold here even more that before.

In fact, the earthquakes have accentuated what was good about living in Christchurch already. Our CBD had to be demolished, with a subsequent kind of regeneration and reappraisal of the spaces outside and gaps between modern suburban life: the sea, hills, mountains, rivers, gardens, and parks. Meanwhile, from the port, along the train tracks, past the cemeteries, industrial estate, warehouses, and, abandoned red zone, to the night-time streets along the East side of the old city centre—this is where the Antipodean Gothic soundtrack of this place that I know has echoed.

Just in case there is any confusion, here we’re talking about the ‘wrong’ side of a broken city – a hole of a city that represents the best aspects of our perverse antipodean location. So once you’re trapped, what do you get up to? Looking to the music that has echoed here we may see how the perverse elements of this physical place are expressed by those who inhabit it.

IV: THE SOUNDTRACK (AN ORGANIC EMANATION OF ISOLATION)

From Waltham warehouses like Log Recording, the Antipodean Gothic OST plays softly along the shadow of the old Jade Stadium, down through the legendary All Plastics Factory and along Stanmore Road to the infamous Pagan House in Richmond. It has reached as far East as the Trike Club in Linwood, which hosted Punkfest, and, at times as far central as more traditional venues such as The Auricle, The Darkroom, The Physics Room, New City Hotel and even good old Churchills, (complete with the sticky carpeted ‘birdcage’ smoking area, hi-vis attired tradies, and copious amounts of bourbon and coke).

The Wunderbar and a few other little haunts in the port-town of Lyttelton have also hosted their fare share of good nights, and there has even been a generator powered ‘Oxstock’ gig in the residential red zone. And, even though most of these venues are spread around a broad area of the East side of the city (the side that has been traditionally less affluent, and the side that has been most damaged during the quakes), the live music scene has been frothing here for the past couple of years at least.

I’m going to have to use the terribly loose term post-punk (in the sense that punk, in its various forms of parallel development, made what came after possible) to cover most of the music that I’m talking about here. Bands like BnP, Log Horn Breed (LHB), The Palace of Wisdom (note the reference to William Blake's gothic poem, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell), and The Dance Asthmatics are holding down the fort. But there are also more than a few improvising artists, many who only play a few times before disbanding or recreating something new, ranging from noise rock to industrial techno (the artist of one such performance wearing a tongue-in-cheek ‘100% Pure Organic Metal’ t-shirt). There’s some synth-driven sci-fi doom (Les Baxters); a bit of melancholy gothic folk (Aldous Harding); a reference to Peter Jackson’s gothic masterpiece in Heavenly Creatures; a nod to a song by punk legends, Big Black, in the title of the threepiece Pavement Saw; an understated homage to drone and black metal in The Hex Waves; and even an odd allusion to Canterbury’s colonial past and its precarious agricultural future in The Plough That Broke The Plains.

Honorary North Island bands, like Girls Pissing On Girls Pissing (GPOGP), and singer-songwriters such as Seth Frightening, have been an integral part of this scene too. So, while none of this music would be described as ‘gothic’ in the conventional genre sense, as you can see already, the band names alone paint a fairly bleak, yet thoroughly entertaining picture. Titles aside, other references or language associated with unease and the gothic are often used to describe this diverse range of utterly contemporary music —both by critics, and the artists themselves.

In an recent interview on Radio NZ National, Seth Frightening was asked to explain his self-described ‘New Zealand Gothic’ genre. He responded simply that it was exemplified by the blasphemous graffiti seen on highway-side farm sheds around New Zealand. An urban art form, and traditionally a marginalised one, offering a heretical message to those driving through the countryside. This has got to be a perverse icon if ever there was one.

Similarly, Dunedin electronic darkwave duo, Strange Harvest, told RNZ they consider their ‘Dunedin Gothic’ aesthetic as both reliant on, and expressive of, the grim and dingy winter weather in Dunedin. Here, reference to the organic elements of the weather in New Zealand’s southern-most city is offered as a signpost to the Antipodean Gothic. Bringing it back to Christchurch based band The Dance Asthmatics, music critic Michael McClelland noted on Terminal Boredom that:

In its sludgy, cavernous way, the music paints a description of NZ's city of sin as if it was a kind of dystopian mecca… While daily life in metropolitan New Zealand is plainly dull, set to music like this it's a fuckin' nightmare realised.

Here McClelland explains how The Dance Asthmatics paint the safe, suburban side of life as the nightmarish one, rather than one to be pursued. These three examples all allude to central elements of the Antipodean Gothic: a turn to the outsider’s heresy (blasphemous farm shed graffiti); a flight from mediocre mass culture (metropolitan NZ as nightmare); and the organic form of creeping natural darkness that hems it all in (winter weather in the South Island).

Though NZ’s cultural export has been largely smoothed over to a tasteful range of visual and sonic landscapes, the dark undercurrent can still be picked up by keen observers. State Laughter Records’ Josh Feigert—commenting on GPOGP’s vinyl debut “Nine of Swords” that his Atlanta-based record label released—provides even more insight into how exactly this gothic stance relates to this antipodean based music today:

In some ways this is very NZ to me, but not in the Flying Nun sense...not even Dead C or Handful of Dust...It does represent a sense of isolation that [I] enjoy in most music from New Zealand and Australia... Detuned twang.....ritualistic and esoteric, but not in a Ouija board, black lipstick sense of pretension... Seriously dark music for those that embrace the pain of being human and not asking to be... Almost a sense of slowly being poisoned listening to this....fans of goth, dark music, maybe a slower, less post-punk, NZ Rule of Thirds for a contemporary might give you a glimpse.

Here, Feigert emphasises isolation – a central trope of New Zealand culture that is seen in our embrace of pristine and empty landscapes. But why? How is isolation relevant to those of us living in urban New Zealand today?

Without a “black lipstick sense of pretension”, you might say this antipodean form of gothic forgoes an easily identifiable, defined or placed aesthetic, image or signifier. It is not so concerned with external validation. Rather, it is understated and nonchalant, though it keeps a certain devotion for the decadent and romantic.

This process doesn’t resolve itself in tidy genres, or even a quickie compilation. It does not actively seek to create something that will be recognised in a certain form, or identified with in a certain way. Rather, it remains to be lost, and then perhaps stumbled upon and found. As such the Antipodean Gothic not only assumes a certain isolation, and therefore freedom, from the goal of market ratings in a modern capitalist system—it also recognises isolation as something organic that cannot ever be fully escaped.

The embrace of isolation is a key aspect of the Antipodean Gothic - in C.K Stead's words it revels in, rather than reels at, aloneness. If the pain of being human is a realisation that we are always alone to a certain extent, it recognises that the embrace of such a reality paradoxically offers us freedom. In an age of instantaneous connection, this is a heretical message.

V: THE PEOPLE, AND A HERETICAL FAITH IN THE OUTSIDER

The outsider offers us a prophetic Antipodean Gothic message, embodying a sincere critical stance that finds critical insight and creative freedom through isolation. Note that this isn’t being an ‘outsider’ in the fashionable and deeply establishment myth of the rugged individualist. Rather, I’m talking about ‘outsiders’ who have thrown away the mainstream ideal of monetary success and its trappings, or who have sacrificed it for something greater. And I’m talking about ‘outsiders’ who have never had the luxury of doing so, suffering from illness or poverty that was not their choice, pressed from birth to offer a different critical perspective on the ‘freedom’ of our white picket fence society.

By choice or not, such heroes of our Antipodean Gothic stories tend to go relatively uncelebrated. Accordingly, a certain faith in the value of their critical perspective or creative output outside what the market prescribes must be present to continue living under such conditions. In an age of cynicism and irony—an age when people don’t really believe in anything anymore—this is particularly refreshing. As McClelland puts it: “Where irony prevails, GPOGP disinfects”.

What does McClelland’s comment on GPOGP with regards to irony mean? More glibly, my local experience of the Antipodean Gothic was that there weren’t too many hipsters all up in it—compared to other local music scenes at least. So, while I can’t comment on the wider New Zealand music scene (GPOGP hail from Auckland), I think I can partially account for this in Christchurch's case. As with so many things this essay comes back to, it’s in the nature of the landscape: being a bit of a ‘hole’ and having suffered even more since the earthquakes, there isn’t so much of a scene for the hipster to revel in compared to bigger cities, and therefore, less of a ‘be seen’ imperative. This allowed room for those who might not quite have fit in otherwise to be a part of the community, and diversify it organically.

The best example of the organic form of inclusion I can think of was when Dean Baldwin jumped up on the mic at a early LHB gig and became the previously instrumental group’s lead singer, transforming what had been a duo into a group which went on to develop a bit of a local cult following. While I sort of hate to comment on the fact that Baldwin is a couple of decades older than the other guys in the band, and while I’m not saying that such spontaneous connection isn’t possible online, there is a certain charm to the materiality of the live scene in Christchurch that changed the experience somewhat for me. Things like this simply don’t happen that often.

I suppose this charm is again based on a stubborn faith in the value of the organic. So, alongside a belief in the organic mode of artistic creation, we can see a certain embrace of the organic mode of live performance, over the placeless, hyperreal or ironic online presence embraced by the affluent and mobile hip in larger centres. I realise this belief in the organic is ridiculously outdated, but the fact that patches still exist where no one seems to care about this, where no one is particularly up on trends that never applied to them, is so refreshing (especially in a digital age of internet trends that seem to be replacing each other faster than you can post a photo of yourself on Instagram with your black lipstick and a #ghettogoth hashtag).

It's this timelessness too, that provides the foundation for a return to a certain sincere, rather than ironic, belief in the creative process, as one that can be free from the need to be validated by Spotify streams or Facebook likes. Here’s McClelland again, this time on LHB:

Irony’s been co-opted like all fuck, and whenever that happens to an idea, there comes inconsistencies within, and voids of, actual self-belief…But self-belief comes in buckets for LHB, in the kinda way that you’d go for a high five and get a handshake instead (actually happened to me twice).

To make a sacrifice in the name of something you think is authentic, beautiful or true is pretty much the height of Romanticism, no matter the age or the particular movement. But it’s a notion that’s been beaten down as cheesy and earnest, like the idea of authenticity, or the ability to exist or think on the margins of mass society. In its place is a climate that that takes apart notions to show it can and leaves nothing in their place, that curates itself, that’s aware of its constraints but sneers at anyone who tries to defy them.

But I don’t see much of this sort of ironic cynicism in the music scene I have been describing. Perhaps there is not such a desire for fame, or, perhaps tall-poppy syndrome makes some of the Antipodean Gothic artists at least pretend not to care too much for it. Those who more vigorously seek a musical career tend to move elsewhere. Those who stay either find enough here, in music for music’s sake, or stay because they subconsciously or consciously enjoy self-sabotage and seeing the waste of their talent.

Maybe they’re happy to be a blip on the radar because it seems more honest in the face of time and geography. Accordingly, the music produced by these people is freed from the need to compromise, or to be validated by financial rewards or their ghostly digital mirror. This might be a lesson for us all in the anthropocene, in a gloriously pre-apocalyptic world, or at least, one where we'll likely be the first modern Western generation that won’t financially ‘out-do’ our parents.

In places where that wave hit harder from others, by nature and by man, Antipodean Gothic offers us a way of making peace with the destruction, or even being glad for it. Either because the wastelands and wildernesses of our culture seem inherently beautiful—as places which honestly reflect our isolation and thus offer us critical or creative freedom. Or, if not, because we are finally learning, or even remembering, a certain respect for the fact that our artists and critics; our heretical, uncivilised, poor and ill; or our beloved outsiders and underdogs, might already find them so. For me, the Antipodean Gothic of post-quake Christchurch continues to remind me of this, and for that I continue to adore it.

An earlier version of this article appeared in the debut issue of Cheap Thrills magazine, from which it is reproduced with kind permission. More on Cheap Thrills, which features contributions from some of the best musical writers and practitioners in the country in print, here.