Change of Fortunes: Lessons from the Death of a Theatre

What's beyond the box office? Kate Prior analyses the conditions around the closure of Fortune Theatre and explores what we can learn for the future of professional theatre in Dunedin.

Three weeks ago, in the middle of a thriving 2018 season, Dunedin's 44-year-old Fortune Theatre closed its doors. In Part One of this two-part article, Kate Prior analyses the conditions around its closure. In Part Two, practitioners and community share their memories of a formidable southern feature of the theatre landscape.

Emily Duncan had an exciting year planned. The Dunedin-based playwright and dramaturg had finally secured a season of her play Eloise in the Middle at the Fortune Theatre. She was working on a commission from Fortune and Otago University, and was leading a bunch of fresh playwrights creating a season of new work in the 4x4 Emerging Playwrights Initiative. For New Zealand playwrights, seasons at our professional mainstages are hard-won. For women playwrights, even more so. For Emily, this was a critical year.

Then on the morning of Tuesday 1 May, the Fortune Theatre Trust gave employees a couple of hours to gather their things before they shut the doors and closed the business. Speaking to Emily on the phone the week after the news, she’s bewildered and burnt. It’s tough to have your work “crossed off someone’s ledger like a disposable commodity,” she says. “Yesterday was a dark day for me. I feel so unmoored.” Ten days after the closure, Emily hadn’t heard any news from the Fortune Theatre Trust board.

What is a city’s professional theatre for? It presents a programme of performance work, it develops younger and emerging practitioners in a professional environment, it supports new writing, it employs and develops arts administrators and practitioners, and it’s an important part of the supportive infrastructure of a national touring network. But a theatre is more than its functions. It does something which is harder to codify: it’s a city’s dream space. It’s local and communal and (ideally) democratic.

Beyond the city, theatres such as Fortune, Palmerston North’s Centrepoint and Christchurch’s Court Theatre have a mandate that feels especially particular to New Zealand. Unlike the metropolitan focus of Auckland Theatre Company or any of Australia’s state theatre companies, these mainstages must serve their surrounding rural communities. One of the letters to the editor in the Otago Daily Times on the Friday following Fortune’s closure was from Alison Anderson in Oturehua, Otago, for whom “never has the four-hour return trip to a production not been rewarding.”

A game of Pin the Diagnosis on the Donkey naturally ensued after the Fortune closed, with players blindfolded by misinformation and often outdated ideas. It’s dwindling audiences; it’s small populations; it’s not enough comedy; it’s "theatre isn’t relevant to young people anymore." If there’s one thing a dead theatre conjures for theatre people, it’s fears of our own irrelevance (or perceptions of it). Regarding the closure, the Court Theatre noted in their statement, “It has been disappointing to see audiences decline in recent years,” which they followed with the quick reassurance, “doubly so because during the same period the Court has seen record attendances.”

The constant ghosty chorus of auuuddddiennncesss has rattled through each decade of the haunted Fortune Theatre’s life. It closed three times in the 80s, there were rocky times in the 90s, and it came very close again in 2000 when the venue was sold to Dunedin City Council to be leased back from them by the Fortune Theatre Trust. Every time, audiences were pinpointed as the number-one problem.

So what of those audience figures? The irony is that last year, under new Artistic Director Jonathon Hendry, audience numbers surged from around 16,800 in 2016 to well over 21,000 in 2017, with numbers tracking well after recent successes like An Iliad (getting Shayne Carter on that stage – a stroke of genius). Likewise, when Jonathon’s predecessor Lara Macgregor took over in December 2010 there was a steady increase in audience numbers for the first two years of her tenure. After a drop in 2013, 2014 saw an increase again, then a decline in 2015. The 2016 season was finalised by the board after Macgregor moved on, and saw a further decline in audience numbers.

It’s undeniable that box office is a coronary artery to any theatre’s financial health, and a small city of 120,000 – one fifth of whom are students – presents a major challenge. But sometimes scarcity produces myopia; the problem is numbers, the only solution is HITS. From the Fortune board I recently received a list of Top 50 box-office hits at the theatre since its inception in 1974. It assigns each hit to an artistic director, like a little AD leaderboard. It’s fascinating. But box office is one very narrow church window through which to look at the potential worth of a theatre and the work of an artistic director. If the art form is going to survive in the iPhone age, New Zealand mainstages need to get to grips with all facets of the opportunity of theatre’s liveness.

It’s undeniable that box office is a coronary artery to any theatre’s financial health and a small city presents a major challenge. But sometimes scarcity produces myopia; the problem is numbers, the only solution is HITS

The work of theatre in the 21st century is to involve community, not only as a prospective ticket-buyers but as engaged citizens. Education and youth initiatives are so often box-ticking offshoots when they can be embedded practices as part of the everyday work of the theatre. It’s true, these activities take time to build and don’t provide the board-pleasing quantifiable measures that box office does, but every single mainstage in New Zealand has an older-and-aging audience base. If artistic directors and general managers are going to secure the health of their theatres beyond their tenures, working to change perceptions and practices now holds greater long-term worth.

Having arrived at Fortune Theatre from two different educational environments, artistic director Jonathon Hendry had a strong sense of this, which makes his short time at Fortune all the more disheartening. Playwright Roger Hall writes in The Spinoff that when he was on the Fortune board in the 80s, students didn’t understand or appreciate the theatre. But if Roger were to focus more on what was happening in Dunedin in 2018 he would have seen that significant in-roads were being made with the vast secondary and tertiary student community. Both Jonathon Hendry and previous artistic director Lara Macgregor understood Dunedin as a student city and structured initiatives towards that. In collaboration with the University of Otago theatre department, Macgregor established a paper that saw students interning in productions such as Punk Rock and Twelfth Night. Hendry was in the process of finalising a collaboration with Otago Polytechnic and had established Backstage Pass, which broke down the walls, took the theatre online, and brought students into all parts of the process of theatre-making. The Fortune featured strongly in NCEA programmes for most schools in the region. And following models in the UK and US, a first successful pay-what-you-can performance had recently been held, aiming to remove one of the biggest barriers to participation in the arts for students and low-income earners. It’s telling that the first public meeting to occur following the news of the Fortune’s closure was organised by theatre students at the University of Otago's Allen Hall Theatre.

Focusing squarely on box office is not only a narrow reference for the function of a theatre, but also an incomplete way of diagnosing cash-flow issues. It’s strange how much of the messaging and public discussion around the Fortune’s closure focused on problems of income through ticket sales and stepped around very real problems of expenditure. This is especially unhelpful if future plans for Dunedin theatre are going to take anything from the Fortune’s demise. Speaking to Jesse Mulligan on RNZ National, Board Chair Haley van Leeuwen noted, “no matter how much money gets pumped in, in terms of funding, the level of ticket sales revenue is not enough to keep us sustainable…What we did not want to be doing is going back to our funders and asking for more of their funds when we knew we were plugging holes versus building something towards the future.” While completely reasonable, it’s a statement that seems to take it as read that revenue drains are out of a business’s control.

So what were those holes? Well, the obvious: the former Trinity Methodist Church, which was Fortune’s striking if anachronistic home, was a significant drain on resources. Not only representing a high fixed cost in venue hire and significant maintenance, it also acted as a barrier to audiences. The steep stairs to the bathrooms on the ground floor were inaccessible for many senior citizens and disabled people, and the small foyer area couldn’t hold the auditorium’s capacity. And that’s just front of house. In the auditorium, the grid and stage area had many compliance issues, the seating area was cramped and heating and cooling would often fail.

The Fortune couldn’t adapt in time. It’s closure wasn’t entirely due to the constant struggle to get bums on seats, but the creakingly slow wheels of governance

Another major cost was the ramifications of the staffing matrix within the business model. The Fortune employed eight full-time and four part-time staff – quite a lot for a small theatre in a small city. The general manager role was hard to recruit for, being a mix of business management, venue management and sponsorship management rolled into one. Since 2008 there have been six general managers – four in the five years of Lara Macgregor’s tenure alone, meaning for several months through various transitions, the artistic director was also fulfilling the role of general manager. Keeping business relationships and the venue alive is hard enough without those responsible for doing so being in a constant state of getting familiar with the role, or it being squeezed within a busy artistic director’s remit.

This prompts some simple questions: If the venue presented one of the highest fixed costs in the budget, why hadn't the board, at some point in the four decades of the theatre's life, let the venue go? If the business model was old and fatty, why hadn’t it been revitalised? Considering there was such high turnover, what work was going in to hiring the best possible talent, within salary means, for the general manager role? (Clue – there’s plenty of great theatre producers and arts managers nationwide in their 30s who might be up for the move south if it meant a career-defining challenge, which also means they’ll stick around for a bit). And if the board could see the financial trajectory of the theatre a mile off, however successful the 2017 season was going to be, why plough on with a year’s worth of business model reviews to no end? The Fortune couldn’t adapt in time. It’s closure wasn’t entirely due to the constant struggle to get bums on seats, but the creakingly slow wheels of governance.

Australian arts advocate Robyn Archer talks about resilience in the arts and what that means. She takes her thesis from a book called Resilience Thinking by scientist Brian Walker. In the natural world, resilience is "the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and still retain its basic function." It contends that systems which are more likely to absorb disturbance are those which focus not only on the high-performing elements (tall kauri like Roger Hall plays), but diverse risks (funghi and fresh shoots like fringe shows, education, youth and community participation).

That diverse thinking relates not only to the output of an arts organisation but their business models. It's worth considering that perhaps Dunedin's professional mainstage, which also serves the regions, doesn’t need a building. Auckland Theatre Company didn’t have one for 24 years, Silo Theatre let go of their building in 2008 and, as the National Theatre of Scotland pioneered, even a national theatre company can be a theatre without walls. Those functions at the beginning of this article, the ones that a city’s professional theatre undertakes – none of them requires bricks and mortar. Neither does being a dream place. That’s the good thing about dreaming.

Thankfully, in ecology and in the arts, failure and fallout isn’t entirely negative. Resilience Thinking outlines that there are four phases in nature: rapid growth, conservation, release and re-organisation. Rapid growth is when artists develop a reputation and make stuff for little monetary reward. Conservation is when growth slows and ideas develop, embed or become entrenched. Release can happen in a heartbeat. The longer the conservation phase persists, the smaller the shock needed to end it. The dynamics are chaotic, but the destruction that ensues means creativity can flourish.

Thankfully, in ecology and in the arts, failure and fallout isn’t entirely negative

In that chaos last week, a steering group was established from a meeting of professional practitioners to start planning the new life of professional theatre in Dunedin. On Sunday they released a statement containing some resonant questions they’re beginning to discuss: “What could a future model for theatre, specific to Dunedin and the region, look like? Learning from the lessons of the past, what do we and our audiences want from a future model rather than clinging to the old? How do we work to keep professional theatre sustainable and create a newer more relevant model that is diverse, inclusive, and representative of our community?”

How exciting is that?

Dunedin City Council has a commitment from Creative New Zealand that it will continue to set aside the $500,000 it had granted to the Fortune each year for future theatre projects in the city. The Council’s contribution, which had been $95,000 this year, has also been set aside for the next three years. The former Sammy's space on Crawford Street has been tabled as an option for a future arts hub with a possible resident professional theatre company. Importantly: the season of plays in the 4x4 Emerging Playwrights Initiative led by Emily Duncan found a venue at Allen Hall. It was staged over the weekend.

Perhaps because of the transient nature of our work, theatre people lean towards the sentimental and nostalgic. It's why we hold on to buildings that are laden with history but are not helping us grow. Yet sometimes for pragmatic future-proofing we need to loosen our grip on the traditional and familiar. By looking honestly at the past failures and challenges of Dunedin theatre, a fresh next phase can take shape. However that happens, 21st-century adaptability is going to be essential: working lean and capitalising on talent and fresh voices; programming astutely but shaking free of box-office myopia which ignores the bigger business and artistic picture; creating ideas that acknowledge the local (not only in product but in practice) as well as collaborating with other national mainstages. Most importantly, a new phase will need to be served by a curious, diverse, action-focused board and management that doesn’t return to old comforts, but capitalises on this phase of research and development.

Over its 44 years, Fortune Theatre has been an essential engine of new writing in New Zealand, a launch pad for some of our best actors, and an Otago and Southland theatre home. To mark the end of this phase of its life, I asked members of the community to contribute their thoughts and memories of Fortune – they’re astonishing, moving, heartbreaking and hilarious – and they’re collected below.

A new phase will need to be served by a curious, diverse, action-focussed board and management that doesn’t return to old comforts, but capitalises on this phase of research and development.

I’ve got a small story too. The one production I performed in at Fortune was the first script Alan Ball (American Beauty, True Blood) ever wrote – a weird fruity comedy called Five Women Wearing the Same Dress. The script goes off the rails in the last third – Alan was still working some things out – but it was some of the most fun I’d ever had on stage. The show was meant to be a Court Theatre production which would transfer to the Fortune, but after the February 2011 earthquakes, the Fortune stepped in, applying for a further $50,000 from Creative New Zealand in order to take on the production first so that Canterbury could still get a brief season afterwards. We performed to 800 people a night at Burnside High School in Christchurch and I’ve never heard laughter like it – they were audiences that really needed a full, silly belly-laugh. The Court managed it thanks to the much smaller lil-tugboat theatre, the Fortune. You get by with a little help from your friends.

Part Two

Fortune Stories

Since the inception of mainstream professional theatre in New Zealand, you can probably count on both hands the number of female artistic directors this country has had. My appointment by the Fortune Theatre Trust board was an indelible turning point in my artistic career, and a responsibility I took very seriously. It’s a position that enabled me to act as a vital conduit between artist and opportunity; provided me with deep and rewarding community engagement across multiple sectors; and at its nucleus, enabled me to seek out, develop, and preserve stories that, in the future, will be a vital resource to understanding our social fabric of that time.

I've been deeply saddened to hear of Fortune's closing. My heart reaches out to Jonty, the staff, the board, the volunteers, the contributing communities of Dunedin, but mostly, the myriad of artists now left with even fewer artistic employment opportunities in this country. I know full well there are many, many components that go into making up the whole of running a funding model like Fortune. It's a balancing act every step of the way – one component goes off course and the whole ship needs huge energy and input from many areas to bring it right.

When you look at similar models nationally (and worldwide) – Fortune, Downstage, Pacific Institute of Performing Arts – that have closed in the last decade, there are definitely big questions 'why,' needing vibrant solutions 'how.' I look forward to contributing to those important discussions, with the knowledge and hindsight gifted to me, ironically, purely through my time spent at Fortune Theatre. – Lara Macgregor, former Fortune artistic director, performer and director

In summer 1984 the Fortune came out of several months in recess. I had recently arrived in Dunedin and heard the new artistic director, Anthony Taylor, needed help at the theatre. Trying not to sound ridiculously romantic here, but I walked into the auditorium and the stained glass rose windows at either end were uncovered, and the sun shone through the colours and the dust, and I was home.

The Fortune taught me what it is to be a 'multifunctional' theatre practitioner. In my early years there, I learned the beginnings of everything I have been honing ever since. Managing the theatre in 2010, working with the team to bring it back from the brink of closure, is the most terrifying, challenging, exhilarating work I've ever done. This time the Fortune, the institution, is gone. The work is gone. The pragmatist in me says work will still happen in Dunedin – the Fortune is just a building after all. But it's a building with hopes and dreams and sweat and terror and beauty and magic embedded in its very fabric. – Karen Elliot, actor and director.

Every experience at The Fortune changed me, as I was straight out of drama school. Suddenly being plunged into the fire of real deadlines and a real audience awoke in me a fierce work ethic and hunger to do as much as I could. The experience that changed me most was doing the solo show Kaz — A Working Girl by local writer Leah Poulter. It was not a strictly verbatim piece of theatre but it had that spirit and was based on a real person. Lisa Warrington directed it and it was a gloriously immersive rehearsal experience which introduced me to the ideas of verbatim, documentary and immersion/experiential rehearsal which have remained with me ever since. I performed that show throughout New Zealand for a couple of years. It was a life-and-work changing experience. I am still lifelong friends with many of the people with whom I went through the company experience, and I admire the contributions those people are still making to the culture – in the performing arts, academia, philosophy, design, writing, education… the value of the Fortune company experience still echoes.

I'm very sad that Dunedin has lost the Fortune. Even now all these years after I learnt so much there, the theatre was still taking risks, building skills, celebrating excellence and fostering a creative community. I love that the theatre was in a church; the performing arts in a living space. I love that Dunedin is a small city and that the theatre could have a huge impact doing work of excellence. I love that so many of the drama students I trained at Toi Whakaari came from Allen Hall – the University of Otago Theatre Department, and that their creativity had been fed by the work they saw at the Fortune over many years. Theatres seem always to be built or exist in the heart of the city, the life of the city swirling around them and being reflected by them. That was the Fortune to me; a company of creative people at the heart of the city. – Miranda Harcourt, director and actor

Two Fortune memories from way back and one more recent: how Rawiri Paratene, as scary, ironically named Clean in Greg McGee’s Foreskin’s Lament, leapt off the stage (but not out of role) to eject an obnoxious punter from the building; how a quiet art installation of police helmets and batons maintained a presence beside Dario Fo and Franca Rame’s farcical Accidental Death Of An Anarchist – a (possibly superfluous but nonetheless satisfying) visual echo of the 1981 Springbok Tour mayhem raging outside; how the production of Samuel Beckett’s Play, in a freezing basement filled with demolition rubble, drew queues and queues of people along the footpath outside, to see one of the most abstract, non-commercial plays of the 20th century. But also how, quite soon in the Fortune’s life-span, the gallery in the foyer – The Fortune Company – came to depict managers and administrators and the cleaner but fewer and fewer artists... until there were none. – Simon O'Connor, actor and director

In 1994 I performed in the Fortune’s production of Michelanne Forster’s Larnarch Castle of Lies in the Larnach Castle ballroom in the midst of a savage electrical storm. The hall filled with smoke and the patrons with terror as it seemed Larnach’s ghost was raging at this theatrical invasion of his lair. Larnach was a phenomenal success for the Fortune because it connected deeply with the soul of its community. The Fortune has been a dynamic arts centre for Dunedin that has relished every style of theatre from Roger Hall to Samuel Beckett. If it weren’t for the Fortune I’d never have had the experience of directing a full professional production of Hamlet with a dream cast and crew in 2005. I mourn the passing of the Fortune as it provided countless creative opportunities for arts practitioners and exemplified a unique spirit of imaginative freedom in Dunedin. – David O'Donnell, Associate Professor in Theatre Studies at Victoria University, director and performer

The Fortune as an institution has always felt as permanent a fixture in Dunedin as the beautiful, challenging, definitely haunted, but much-loved gothic building in which I've known it to exist. It shouldn’t have made any sense, but somehow it felt perfectly natural there in its church on the hill in this strange southern city of artists and bookshops. Lately I came to know it as something not old and imposing, but as a living arts venue, struggling along with the rest of us through booms and busts that connect with its name – a throwback to gold rushes gone by. I’ll remember it for giving us the chance to perform The Devil’s Half-Acre, set in the slums of 1800s Dunedin, on the site of the real half-acre, in a building that stood there at the time. For us it was both a homecoming and a rare opportunity to return to an ambitious festival show, to have a second crack at things that had eluded us at first. Its demise leaves a gothic shaped hole in our wee community – we pull our coats tighter around ourselves, batten down against the wind, and strive for better fortune in the weeks and years to come. – Ralph McCubbin-Howell, writer and actor

The building has been closed. It carries the memories (more or less, along with a few earlier venues) of over 44 years of continuous professional theatre in Dunedin. That includes 37 years of my own theatre work. It seems like a lifetime, and it is – a cavalcade of productions (nearly 40) I have directed there, and a few I have acted in. It has been HUGELY important to my own theatre career, giving it a focus and a sense of purpose.

The building has been closed. But many of the people are still here. And there is still a living heartbeat of professional theatre pulsing in Dunedin. It just needs a little help to refocus and regroup. All those people with creative passion – what could we become, in the spirit of what the Fortune has been? There is a future. Even though the building has been closed. – Lisa Warrington, Associate Professor in Theatre Studies at Otago University, director

My strongest and most pertinent memories of the Fortune are those productions that prompted me to think as a playwright, like John Broughton’s 1981, directed by Jim Moriarty in 1995. The play explores the 1981 Springbok Tour and is told from the point of view of a Māori family comprising Faith, a law-student protester, Rusty, a member of the police Red Squad and Ben, who is a farmer and rugby fan. 1981 ignited possibilities of spatial and visual storytelling and it was a pin anchoring the string of my theatre consciousness back to my law-student mother protesting the Springbok tour, forward to my recent work with actor Julie Edwards, and circling Ralph Hotere’s A Black Union Jack? which hung in the theatre until it closed. 1981 dared: tell your truth and make a stand. Take a risk and place your work in the empty space and summon others to join you. I needed this confidence and courage as a young writer, as do the young writers who follow. – Emily Duncan, playwright and dramaturg

I count myself hugely fortunate to have had a 35-year part-time career in literary management / dramaturgy at the Fortune, an opportunity few people living in a small city in the English speaking world could hope to have. I have a memory of acting in Roger Hall’s After the Crash in the 80s. The first act concludes with a punchline and a quick curtain. However, one night the Stage Manager responsible for closing the curtain was not at his place – he was elsewhere organising some moonlighting work for himself on a tele-movie. We were trapped there in full public glare, six characters in search of an author, or a stage manager. Eventually we all just walked off. Audience confusion ensued. The air was blue in the dressing room when the Stage Manager was located. He didn’t last long in show-biz after that.

To lose a professional company after four decades is a tragedy for Dunedin (and New Zealand) audiences, drama students, writers, performers, theatre craftspeople and technicians. As an arts institution the Fortune’s merits were insufficiently recognised by funders, central and local. In 2009 its production of A Streetcar Named Desire went to an American Tennessee Williams Festival. How many other New Zealand theatre companies can say as much? – Alister Macdonald, Fortune dramaturg and board member

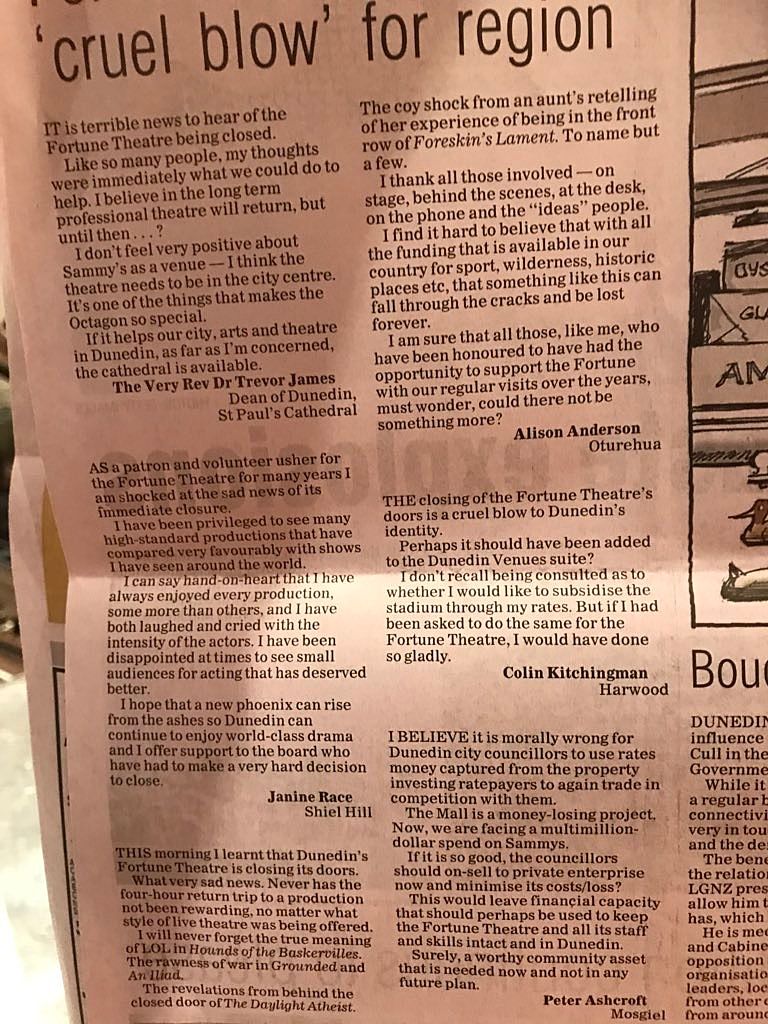

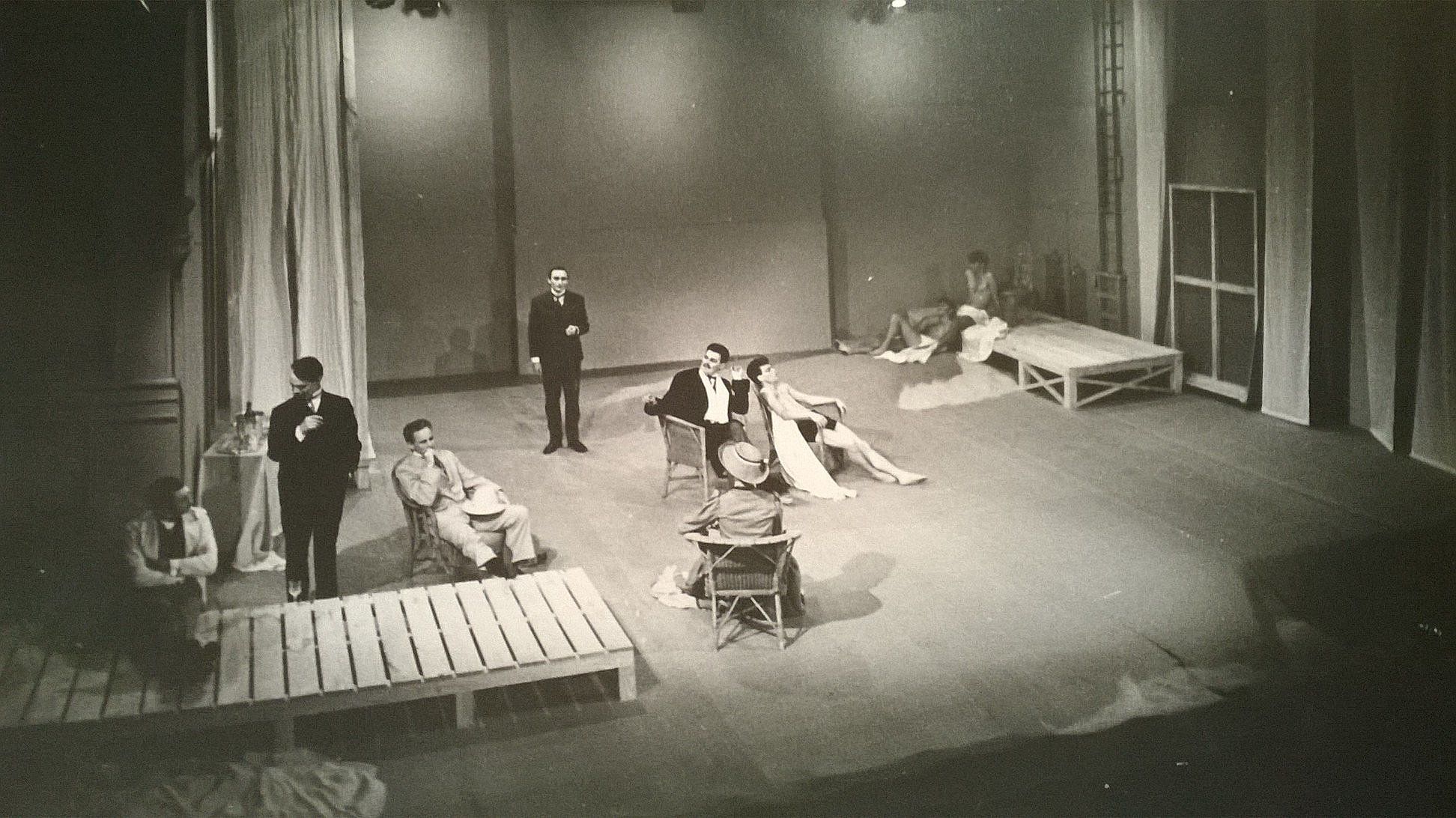

I started my career as an actor at Fortune Theatre in 1984, and my first production was A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a wild and visionary interpretation of the play directed by then-Artistic Director Tony Taylor, who also designed the extraordinary pared-back white set. I worked at Fortune till the end of 1985. We did theatre-in-education in the morning, touring schools: Miranda Harcourt, Bev Reid and I performed a play called Schoolyard Games on a massive set-piece jungle-gym that we had to cart with us in a van and assemble in school halls. We rehearsed for the next mainbill show in the afternoon and performed at night. We also had company classes. I was 22 and it was amazing. The Fortune Theatre: freezing backstage in June, hearing the bogans doing burnouts on Stuart Street during the quietest bit of the show on a Friday night, squished into the impossibly tiny bar as an audience member, cooking real scones in Wednesday to Come and eating them onstage during the interval…I’ll miss it all. – Hilary Halba, Associate Professor Theatre Studies at Otago University, actor and director

The Fortune holds a special place in my heart. It has been instrumental in creating my love of theatre. As a practitioner, I made my professional stage debut there and opened the world premiere of a play I co-wrote with my dad. But the most significant moments have been as an audience member. From age eight, I went to every opening night. We’d put on our best jerseys – it was always freezing – and head down the hill. On approach, the theatre seemed to glow; some magical energy beaming out of the stained-glass windows onto the dark streets. I don’t know if it was the old church building, but walking through the doors felt like an act of reverence. The plays blur together, but what remains is the feeling: the crackle of excitement as the bells called us in; the moment the lights went down; being transported into another world; the collective experience of going on a journey together; the thunderous applause, and on the odd special occasion, being swept up in a standing ovation. Afterwards, we got to go backstage and meet the actors. We often stayed for the parties. It all felt impossibly glamorous. – Pip Hall, playwright and actor

My very first professional gig as an actor in New Zealand was given to me by Lara Macgregor. It was a touring production of Two Fish ‘n’ a Scoop which ran for three weeks at Fortune before a two-week tour of Southland. It was full noise. New small town every day, big demanding role and in the middle of winter. The crew down at Fortune Theatre were the real deal; they knew their craft, they made some great work and were incredibly warm, lovely people. Being down in the bottom of the South Island you can feel cut off from the buzz of the big smoke, but when you were working down there it didn't matter. You were just trying to get the best piece of work up on its feet for the audiences down there. That's all that mattered. Which brings me to the audiences. There is something incredibly satisfying about performing work outside of your bubble. Don't get me wrong, performing to sold-out houses of young Auckland Queers is a future I'd be happy with, but there is some undefinable beauty about performing work to packed-out halls in Ranfurly, or Cromwell or Alexandra that makes you feel so connected to New Zealand as an artist. Everyone deserves good storytelling, powerful imagery or simply a fun live night out – no matter where in the country you live. I love that the team at Fortune Theatre shared that so widely around New Zealand. – Chris Parker, actor and writer

I remember as undergraduate students we always had complaints about the plays that were programmed at the Fortune – not fully realising the economic realities of producing theatre in a city the size of Dunedin. The people who were worked there were always incredibly warm and welcoming and put their hearts and souls into their work. The theatre provided many opportunities for young theatre-makers, through internships and their 4x4 Emerging Playwrights Initiative. I had an opportunity to shadow Lara MacGregor when she directed Sarah Ruhl’s In The Next Room, which was an incredibly educational experience. Every fortnight the Fortune allowed our improv troupe to use their studio space at 10.30 at night, and every fortnight our sleep-deprived audience would turn up to see some nonsense. The Fortune was a home. – Alex Wilson, director

Fortune played a big part in my writing life. For many years, particularly under Campbell Thomas, Fortune was the place that premiered my works and I owe him, and them, a lot. In no particular order: Love off the Shelf, the musical spoof of Mills and Boon romance novels saw a standing ovation – particularly sweet after the Court had originally rejected it; Social Climbers, five women teachers stuck in a tramping hut for the weekend, plus a daughter played (very well) by my own daughter, Pip; By Degrees, four middle-aged women talking directly to the audience about taking a degree late in life – I stuck to my guns by not letting the characters talk to each other; The Hansard Show, not a hit, this, but Campbell Thomas lovingly re-created Parliament’s debating chamber as the set. Two plays hit the mood of the times exactly: The Share Club and its follow-up After the Crash (at the opening night of the latter was a share club from Timaru. They admitted rather ruefully that they’d been planning a trip to Hawaii, but that this was it).

Best all was a special performance of Footrot Flats: The Musical in which the audience were invited to attend as Footrot characters. The place was packed with Wals, Cheeky Hobsons, Dogs and Jesses, Cooches, Aunt Dollies, Cecil the Ram, Prince Charles the corgi and several sheep. Hard to know who was having the more fun, those on stage or those not. Dead heat, I’d say. – Roger Hall, playwright

I did my first show at the Fortune Theatre in 2000. It was Much Ado About Nothing, I was 19 and I played Hero. My heart was exploding with joy and nerves – a big theatre, grown-up actors, period costumes, a stage kiss. I discovered the joy of the dressing room – the gossip, the rituals, the bonding, the rude jokes, the raucous endless laughter. I loved the dressing room more than the show – I would arrive at the theatre extra early to get more of this sacred time, hanging on every word of the other actresses, watching closely how they did their make-up and hair, what perfume they wore, stammering every time they asked me a question. I can still remember where everyone sat and what it smelt like. The dressing room is still my favourite place. – Anya Tate-Manning, actor and writer

The last time I performed at the Fortune I played to six people. Down the road, a naked performance artist licked her way out of a sugar sarcophagus: Otago Daily Times’ front page news. I raced through my show and took my audience to see it.

I was there to see Lisa Warrington direct Three Days of Rain; Simon London in Equus; Josephine Davison and Neill Rea in The Blue Room; Jen Ludlam and David McPhail in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. Simon O’Connor doing just about anything. So fucking good. I was also there for the opening night of Othello. The lead was a no-name British soap actor, imported at great expense. His memorably terrible performance was upstaged by a multitasking director/artistic director/actor who neglected to learn his lines. He had them fed through an earpiece I could hear from the back row. I saw dozens of similar productions that formed the internal dilemma of my career: Try to participate in Creative New Zealand Toi Tōtara-funded theatre? Or stomp it to death? My aggregate Fortune experience is empty, uncomfortable chairs. Everyone wanted out. Out-of-town productions didn’t want in. Practitioners were more and less subtle about their opinion that Fortune was sucking the funding oxygen out of better schemes. We’ll see if they were right. – Arthur Meek, playwright and actor

I grew up going to the Fortune. It wasn’t until I left Dunedin I realised you could have a theatre that wasn’t in a crazily converted building. It’s a theatre that depended on legacy knowledge to function because everything about it is quirky. During our recent production of Troll at the theatre a car accident caused all the power to cut out so none of our lighting functioned. Luckily Lindsay, the Fortune house tech of many years, came in on his day off and flicked some mysterious switches in a cupboard on and off again, fixing the problem. Its demise is a tragedy for the city. When Ralph [McCubbin-Howell] and I discuss (read: argue) about what we will do in our future I regularly proffer Dunedin as an option – “It’s so cheap! It has more professional theatre than Wellington!” Sadly I am going to have to let that argument go. – Hannah Smith, director

I saw my first-ever professional production at Fortune and I began my career as an actor on its stage. Then, 28 years later, I was able to return and have the pleasure of working there again. From Tony and Ianthe Taylor and that amazing group of people there in 1985, I learnt (by observation as much as by instruction) stagecraft, etiquette, lore and history, but above all, respect – for the work you do and the people you do it with. They taught me the power of the collective and the true meaning of the word 'company.' It had nothing to do with the walls we all worked within – it was always the people. Everyone who has worked at Fortune Theatre since it began has wanted to be there; has wanted to create and present the very best that theatre can be. And I am forever grateful. – Andrew Laing, actor

In An Iliad, Shayne Carter and I were the last main-bill performance at Fortune. The two of us worked on a set that, somewhat prophetically it seems, resembled an abandoned theatre. I felt privileged to be telling that story, to have all of my craft demanded of me, and to be playing in a space that had theatre history in its bones. It was an experience that I will never forget and in terms of my personal development, a much-needed shot in the arm.

But Fortune itself, the building, seemed to stand in another time. It’s creaking back-stage, the cobbled-together dressing rooms, the fading photographs of companies from the past, old furniture and half-hidden shelves full of books and long-unused props, all belonged squarely in that period when we had fully professional theatres the length of the country, with companies of actors who had regular work and could develop their skills as they plied their craft. I enjoyed the nostalgia, while at the same time it was clear to me that the whole atmosphere of the place was telling me “adapt or die,” which is surely a message for theatre everywhere.

The performances that Shayne and I gave of An Iliad will stay with me forever. They were made especially powerful because of that unique old building that had seen so many of us through the years. – Michael Hurst, actor

I'm still working through what has happened and it will take some time to really get my head around these exhausting and rewarding couple of years. I have to process a lot – including feelings of failure and regret.

There’s been some generous feedback acknowledging the work we were doing at the coal face. It's heartening that people saw us use our skills to engage communities and have them explore possibilities with us. Strategic partnerships with the tertiary sector and business were growing as we looked to adapt. It was the area of social participation that I felt most excited about. Dunedin is a remarkable small city with progressive thinking and great possibilities for arts innovation. I’m proud of the way we were developing new writing, employing many more local emerging artists and presented more new New Zealand work with the reward of a resurgence in audience attendance over the last 16 months. Especially the growing number of patrons under 30. My mandate from the Board was to attract audiences after all. I know I put my heart into it.

Recently Shayne Carter had this great comedy schtick in rehearsal as he was moving into new territory and taking risks playing, engineering and at times improvising work in front of an audience. As things naturally didn’t go to plan all the time he’d smile and say “Hah! Give-it-a-go Carter at it again.”

Well damn it – the job was a challenge from the outset and I sure gave it a good go. – Jonathon Hendry, Fortune Theatre Artistic Director until May 1, director and actor.

This week we’ve been focussing on the state of New Zealand theatres that serve the regions. You can read the companion piece to this, regarding Palmerston North’s Centrepoint Theatre, here.