Cataphoric Coop’s Closing Night

At the Upper Queen Street and Newton Road intersection, behind two enormous billboards, is captcha – an artist run space, which opened in May this year. On Fridays and Saturdays, captcha is open to all; the rest of the week it's a home to its four flatmates.

At the Upper Queen Street and Newton Road intersection, behind two enormous billboards, is captcha – an artist run space, which opened in May this year. On Fridays and Saturdays, captcha is open to all; the rest of the week it's a home to its four flatmates.

Between 20 October and 18 November, captcha exhibited Cataphoric Coop – a show by artist Tom Tuke with an accompanying texts by Rhydian Thomas and Amber French.

Tuke is an Elam graduate, who finished his teaching degree this year. Next year, Tuke is thinking about moving to Hokitika to make art because “it’s really cheap” and to be close to his family. Rhydian Thomas is a Wellington-based writer and musician, who recently published the dystopic novel, Milk Island.

For the show’s closing event, I had a conversation with Tuke and Thomas about New Zealand’s politics, dystopias, satire and the Austrian architect Friedensreich Hundertwasser. captcha promoted the event as a:

“Projected future, fun and futile. Tuke’s Cataphoric Coop is an acrylic on wood, sensible yet delightful, centrist future in which Hundertwasser is hot, and the community is a-buzz w lyres and liars. Rhydian’s Despair series will seem fucked up, touch concrete. His ongoing interest in nihilism, dairy and toxic father-son relationships is on full show here.”

Eloise Callister-Baker: Tom, can you tell us about Cataphoric Coop?

Tom Tuke: I made this work when Winston Peters was deciding the government. I had also interviewed someone who had been working on the Hundertwasser Museum in Whangarei. I was thinking about the art scene in Northland and the rhetoric about Northland in the election cycle. This led to me thinking about what would happen if Winston Peters became Minister of the Arts when he was on his last legs. My work is a satirical allegory. I was also reading Rhydian’s book while I was working on this work.

HUNDERTWASSER WAS AN Austrian architect and artist. In the 1970s he moved to the Bay of Islands and spent his last days there. In 1999, his iconic toilets were completed at Kawakawa.

Tuke describes the toilets as “the most game-changing community art work in New Zealand. Before them, Kawakawa was a down and out town that Aucklanders drove through on their way north. Now people stop in Kawakawa because of these buzzy, Austrian toilets. They go to cafes and the historic railway museum – it’s genuinely changed the town. I made this work imagining Winston thinking of the toilets as the ultimate art work and putting them in every town in New Zealand. That’s my dystopia – the Hundertwasser model being pumped into the mainstream.”

Before he died, Hundertwasser designed a museum for Whangarei’s waterfront. “When Winston won the Northland by-election, National was trying to work out how to pump life into Northland without doing the same things Winston had promised. Steven Joyce went to Whangarei and worked with a group to start funding this art museum,” says Tuke. National has contributed up to $7 million on the project. Northland Inc (the Regional Economic Development Agency) calculates the museum will have a direct economic impact of $37 million for Northland with an ongoing economic impact of $26 million per annum.

The museum will be home to a gallery of Hundertwasser’s work and a contemporary Māori art gallery. It is planned that the project will be completed in 2020.

TT: The history of art and education is really interesting in Northland. It's been built up as a legend, but I think there's some truth to it. The flame for contemporary Māori art was ignited in Northland through the Northern Māori Project. There were native schools in Northland that had an arts focused curriculum. There were people like Cliff Whiting, Ralph Hotere – a whole bunch of really influential teachers and students under those teachers who were real kickstarters of the contemporary Māori art scene in New Zealand – crossing over the urbanised Māori with the traditional to make contemporary Māori art.

TT: It's pretty offensive that this Hundertwasser museum is being built when there are people, like Cliff Whiting, who made this amazing wharenui at Te Papa in Wellington. There are so many Māori artists who have benefited from their time in Northland who could have a museum named after them. It doesn't have to be this Austrian guy.

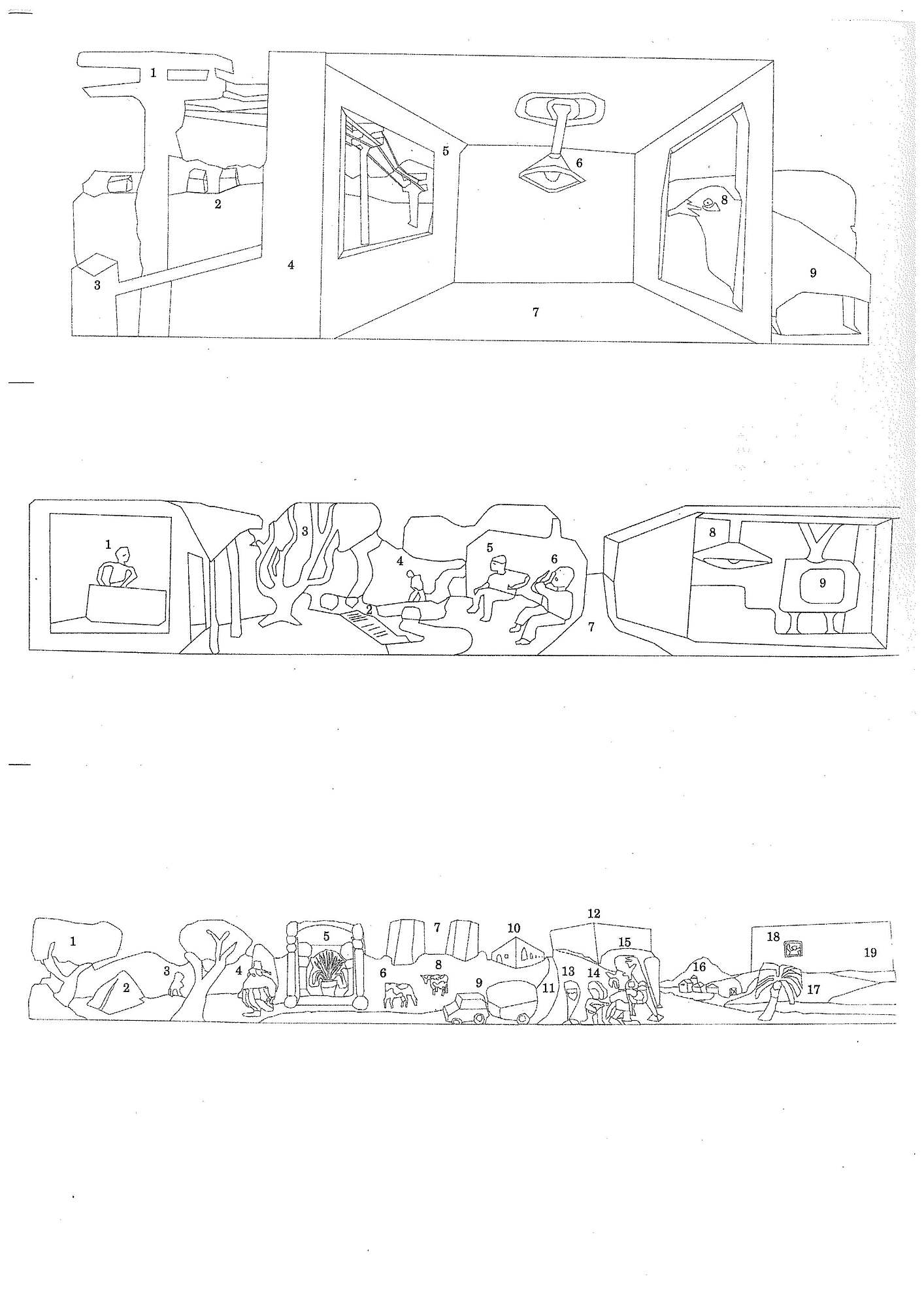

IN RESPONSE TO Tuke’s dystopic, narrative carving, which has Hundertwasser’s toilets at its centre, Thomas wrote three texts that corresponded with the numbers placed throughout the different scenes depicted in Tuke’s work. Thomas read the following texts to the audience during our conversation.

Rhydian Thomas: When I wrote about this work, the vector graphics were all I had to go on and the name of the show. Inevitably, I projected myself onto it. It’s all about me. This is the first time I’ve seen the work in colour and in its three-dimensional shape.

ECB: Tom, what’s it like to have your work written about in this way?

TT: It feels very special. Some of the works I have kept in my room for a long time and they have lost their initial meaning. It’s interesting having Rhydian and Amber pump the life force back into these empty structures, even if that life force is really nihilistic. In his third story, Rhydian says, “I was disappointed that these same processes were in play everywhere: certain consequences, and sometimes those consequences could be anticipated in advance of their causal conditions. In disgust, I sought to change the entire relational nature of causality. I travelled the next leg of the journey by car.” This speaks to where I was coming from when making this work.

ECB: What’s it like to work with these kinds of constraints, Rhydian?

RT: I like constraints, especially when it’s essentially a commission. I know it’s a writing school cliché, but formal constraints make you innovate within what you’ve been given. I found what I did here was an incredibly narcissistic act. It was a projection of myself into someone else’s work, which I think we all do necessarily when interpreting someone’s work out of context; this work was especially decontextualised. In the end, I succumbed to total introspection and narcissism. I pursued paranoia, doubt and hesitance. I wanted to laugh at myself as well.

Wellington art scene is inherently douchey, especially when writers get involved. When writers write accompanying forewords for exhibitions, they’re always incredibly overwrought and have this sense of trying to make everything timeless, whereas looking at Tom’s work I know this is work that’s from right now and describes the contemporary political situation.

I’m interested in art and I’ve made a little bit of visual art here and there, but I felt like a naive person coming to it, which is really interesting. I enjoyed that sense of not really understanding the formal basis or the historical context and just looking at a JPEG on a computer screen and making shit up.

TT: When you say your work is narcissistic and about you, are you actually talking about your father (who is mentioned throughout your texts)?

RT: Nah, not at all. My dad was a dick when I was a kid, but he’s alright now. I never got over existentialism. I read Sartre and Camus when I was 18. I projected my own paranoia and conceptual framework…

TT: …into a power pylon.

RT: Yeah, absolutely.

ECB: How did you create the dystopia in Milk Island?

RT: I started the book about seven years ago and it only came out this year. I've been compiling notes. I went to work at Parliament for about 3 or 4 years in different roles from a low-level secretary to a political advisor/spin doctor. Everything I did in my real life, I was stowing away. I hated it. I met so many evil human beings. I never thought it was possible that all the clichés about people who work in politics could be true. I took all these absurd one-offs, like I'd get a letter from a constituent saying the alien police are controlling their mind and want them to kill people or I'd read a Federated Farmers brochure about 100% pure New Zealand dairy and how beautiful and organic it all is. I built a system for 2023 – what it would it look like, what ministries would exist, who would be the ministers in charge. I created a political framework of what the government would look like. It was a scrap book in a way. The world already exists to me, anyway.

Nothing's going to change because my book exists.

ECB: Have you received any backlash?

RT: No, not really. It's a novel – who gives a fuck really? Somebody told me they wanted to kill me and I got an email saying ‘I should fuck off back to Wales’, but largely it's pretty inoffensive. Many people just say, I liked your novel, but you write quite long sentences. That, to me, is the most withering criticism. If it starts going any further, maybe I'll get into trouble. Ideally I'd get sued by the Federated Farmers or the Sensible Sentencing Trust – that'd be great, that'd really set it off for the 5th print run. If you know any comms reps from farming agencies – tell them I took the piss out of them.

ECB: Does what you’ve written for Cataphoric Coop link in any way to Milk Island?

RT: Tom had told me that he had read Milk Island. My future world in the book is based on the National Party going into five terms of government and turning the South Island into a dairy prison where prisoners work off their social debts in cheese exports and such. Tom read that and thought about the ultimate scenario – Jacinda and Winston in five terms and the political project they would pursue. It got me thinking, what would be better about that? I have total despair about that too. It’s related, but in Milk Island I was a character and occasionally I wrote as myself, but in this I got to write as a halfway point.

ECB: Tom, can you explain the dystopia you have depicted in your work?

TT: Rhydian’s book predicts the National party being in government for five terms. When he was writing it, that was definitely probable.

RT: Totally. My book’s irrelevant now. The present reality should be gross enough already, so I shouldn't have to do what I did in my book.

TT: And we don't have to do it. It's not actually helpful.

RT: Nothing's going to change because my book exists.

TT: And nothing's going to change because of my work.