By Your Place in the World, I Will Know Who You Are

This essay on place, identity and home is excerpted from Extraordinary Anywhere: Essays on Place from Aotearoa New Zealand

Last year I attended a hui for a new job and was among a group of people who were, for the most part, unfamiliar. I knew a handful of attendees, so in one of the breaks I greeted an old acquaintance, and she introduced me to the other people in her group.

She said something like ‘Tina is a writer’ by way of introduction.

‘Oh?’ said one of her group, then she looked at me intently, curiously and without recognition. ‘Where are you from?’

At this point I did what I always do when faced with this question. I stumbled and stuttered, and muttered something about being from all over the place, but currently, up the coast.

‘The East Coast?’ she asked, her interest piqued.

‘Uh no, Kāpiti Coast,’ I replied, and stumbled around further, trying to find purchase in this exchange of niceties that is quintessentially Māori.

What I like about this encounter, despite my discomfort, was that the woman enquiring of my origins was blond and had Pākehā features. I had thought she was Pākehā, and perhaps she was, but when she spoke, her intonation and her question immediately revealed something about her cultural origins or associations. Her expression was one I have only encountered from Māori seeking to make connections. And her question meant: ‘I will be able to place you if I know where you’re from. By your place in the world, I will know who you are.’

As soon as this happened, I felt culturally inadequate, but that had nothing to do with skin or features or any outward expressions of identity. It was about knowing your place in the world.

Each time I encounter this question, I feel like I fail a small test, no matter how hard I work to come to terms with the lack of precision and definition in my answer.

*

Sometimes, writing a personal essay feels like a constant argument about place — the place I belong, how I place myself, my place between cultures — a constant wrangling between two sides that at its simplest is embodied by my Māori and Pākehā parentages. The marriage between my Pākehā father and Māori mother didn’t work, and they separated when I was still a toddler. My sister and I were brought up by our father. It’s not important to go into the details of that, suffice to say I still remember the exact moment when, as a teenager, I began to see my parents’ relationship as a microcosm of the historical relationship between Pākehā and Māori. This analogy was of some use to a confused young woman, although time and maturity eventually caused me to view my parents, and history, as more complex creatures. However the outcome of all of this was something that doesn’t make much sense, something paradoxical if you will — A Māori who doesn't come from any place in particular. Tūrangawaewae or papakāinga are widely held by Māori and Pākehā as defining features in placing who Māori are (often translated, respectively, as ‘place to stand’ and ‘homeplaces’, also known as haukāinga). As Indigenous peoples, as Treaty partners, as tangata whenua, knowledge of and relationship to ancestral land is paramount in explaining and maintaining not just personal but political and economic claims to tino rangatiratanga, or sovereign status. Knowing where you come from really matters.

I still remember the exact moment when, as a teenager, I began to see my parents’ relationship as a microcosm of the historical relationship between Pākehā and Māori.

But if I am asked where I come from, I can’t give a direct or single answer. This is particularly problematic when meeting other Māori, for whom it is more common and polite to ask where you’re from than who you are. Not only was I brought up without any knowledge of my papakāinga, but we also moved places every year or two. I do not have a ‘hometown’, even in the Pākehā sense.

This void or absence should not be confused with not having any relationship to homeplaces. I do have multiple papakāinga; that is, I have several mountains, waters, lands and marae that I connect to via whakapapa or genealogical and familial links. These are my places to stand, and I can go to any of them at any time and find myself ‘home’. I don’t mean some ephemeral, non-experiential sense of home; I mean that they quite literally, physically embody home spaces for me. One summer several years ago I was doing novel research in Waikawa Bay, Picton. I hoped to find evidence of stories I had heard about my ancestry that had inspired the fiction. Waikawa is my grandfather’s marae and therefore very much mine, but I had not been there for approximately a decade and we knew few people who still lived in the area. My first stop was the urupā (cemetery) where I could greet my ancestors and seek the ones related to my story. It is an extraordinary place at the height of summer, high on a hill above the Sounds, and I always feel as though the tupuna get a pretty nice view to watch over for all of eternity. I took my children exploring with me and told them what I could of our connections, and as we were leaving we visited a second spot with additional graves. Here, an aunty took me in hand. Who were my people? she asked. I told her my grandfather’s name. Oh, you’re one of ours. Are you coming to the marae? There’s a tangi, one of your relations. Come have a kai. Do you have somewhere to stay?

And so, even though I hadn’t told anyone we were coming, even though I wouldn’t have known who to tell we were coming, there we were, home, and not one person looked at me like I was a stranger, even though I kind of was. I was theirs, they were mine — that was my place. It is possible for me to do that on six marae, maybe more. Nothing I write in this essay and none of my discomfort refutes the fact that they are inexorably my places. But I wasn’t brought up near them. I did not spend my childhood playing around their marae ātea, or sleepily looking up at the rafters of the whare while hui went on for days. Most Māori identify more strongly with one or two places, one or two iwi. Mother and father. Even if we leave out the fractured beginnings and the Pākehā upbringing, I have trouble claiming just one or two of these marae as my main places. Where are you from? For me, the answer is at least a paragraph, if not a page. Never a sentence.

Where are you from? For me, the answer is at least a paragraph, if not a page. Never a sentence.

It feels somewhat ridiculous to be concerned about this — six marae, maybe more? Surely I am drowning in cultural riches. But the ahi kā, also known as ‘keeping the home fires burning’, is a tikanga that can’t be discounted. If I don’t live by these marae, if I don’t contribute to them regularly, if the people there don’t see my face each month, or even year, how can I maintain my place there? I’m a townie. I live where I hope to make a good life for my children. I choose to expend my cultural energy in writing and urban cultural activity, for the most part. I operate in the wider world as Māori even though I don’t always know how to ‘be’ Māori when Māori are by definition tribal. For example, I can’t choose between my western or central dialect: should I say ‘whakapapa’ or ‘w_akapapa’? There is whakamā, which translates as something like shame or embarrassment, in all of this.

Put simply, there is an expectation that Māori know where they come from, yet I write as a Māori who doesn’t have grounding in one place, one tribe, or one culture, but who is still Māori. I am Pākehā too. I am not part-Māori and part-Pākehā; I am both Māori and Pākehā.

One great solace and encouragement is that while the specificities of this story are uniquely mine, the outcome is not — we, whatever we are, are everywhere. There are labels — variations on hybrid, urban Māori, ngā awarua. There’s even a movement to reclaim the title ‘half-caste’. It really shouldn’t be such a big deal anymore, except I still can’t answer a simple question, ‘Where are you from?’ and I still meet young people who are deeply conflicted, even ashamed, about their multiple heritages.

we, whatever we are, are everywhere.

I often think of writing in terms of paradox.

How can two seemingly opposite ideas exist in the same place?

Do they actually exist in the same place? Are they actually opposites? How can someone be from more than one place and more than one or two or five peoples?

The place I write from comprises two opposite and conflicting ideas: one, that I absolutely belong to multiple places in Aotearoa, that I have inalienable rights to those places as tangata whenua; and two, that until I was almost an adult, there was a void in my life where papakāinga or homeplaces should have been. A void which also should have been occupied by cultural and familial knowledge, and which is no longer unusual among either Māori or Pākehā. This paradoxical place is extraordinarily powerful to write from: teetering on the edge of the void, buoyed constantly by absolute belonging and knowledge subsequently gained as an adult. It is the pain and loss and discomfort of the void thrown up against the wealth of what I now know that informs what I do. It’s something I’m grateful for every time I write, because writing is itself an enactment of that very same tension: of what we don’t understand, what we yearn for, what we seek, and what we know utterly, at the level of bones.

How can two seemingly opposite ideas exist in the same place? Do they actually exist in the same place? Are they actually opposites? How can someone be from more than one place and more than one or two or five peoples?

I have written about Māori versus European conceptions of the universe, Pākehā-Māori ancestors from the 19th century (the original hybrids) and about loving museums and being confused about their history of containing and misrepresenting, even maiming their collections, including people. I’ve written about how crucial it is to use Māori words in English-language stories, the strange rightness of a carved tauihu in a European museum, the feeling I sometimes have that ghosts might linger in my writing, or maybe that is just a way to explain things. In each of these essays, there is a tension from the first line — this is how I know I should keep writing. Even now I feel it, the impossibility of making what I’m trying to say clear, transparent, sensible, straightforward. It isn’t. Māori and European systems of understanding the universe are almost identical, except in the ways they are not. Pākehā-Māori were Europeans who assimilated themselves into Māori culture by choice and desire, except they were still Pākehā. A carving from a 19th-century waka should not belong in a museum in Frankfurt, except that somehow it does.

The essay is the perfect site to explore paradoxical questions because an essay is supposed to be nonfiction, which means it is supposed to be about a knowable truth. And yet the essays I enjoy circle around the unknowable, constantly trying to place a finger on what something is, constantly searching for answers to questions the writer knows are, at some level, unanswerable. Fiction does this too, but fiction has permission to do anything it wants. Don’t know who you are? Make something up! With nonfiction there is a tension already on the page from the moment we touch pen to page or fingers to keyboard. The tension comes from nonfiction’s imperative to write something true when we don’t even know if that’s possible. Essays ask us to achieve the unattainable, like being multiple things and coming from multiple places all at once. How do I understand the complexities of a simple encounter like the one at that work hui, with all its layers of culture and nuance, differing understandings about the significance of not just physical but cultural place, and appearance? I write a personal essay, though I’m not sure I will find my way to any particular answer by the end of it.

With nonfiction there is a tension already on the page from the moment we touch pen to page or fingers to keyboard. The tension comes from nonfiction’s imperative to write something true when we don’t even know if that’s possible.

I love the challenge and the impossibility of the form. I can gather evidence. I can draw pictures, design diagrams and problem-solve. I can quote the greats. Occasionally, I can capture a reflection, sample soil or draw blood. I might even get satisfaction from evoking a sense of how I understand the world, but what I can’t do is present what I have written as fact. The Way Things Are is changeable, difficult to corral into tidy yards. Things like place and identity can’t be captured, but fleeting glimpses of them can be. I struggle with those personal pronouns at the centre of the personal essay — the great ‘I’ and ‘me’. But what I’m really talking about — by extension, I hope — is us. How does it work for any of us? What does tangata whenua mean in this moment?[3] Suffice to say that the essay is a place where we can make, as Albert Wendt pointed out in his iconic 1976 essay ‘Towards a New Oceania’, our individual journeys into the Void, where we can explain us to ourselves. I have used the essay as a site to make ancestral journeys, and these explorations have only complicated my understandings of where I come from, rather than simplified them. There has been no single path, no single people, no single place that takes precedence in these stories. But knowing the stories, getting closer to the heart of the contradictions, has taken away some of the whakamā. I can only view the complexity of what the tupuna have left behind as a gift, a place that offers comfort even where it does not provide certainty.

Postscript

A new question arises now, one I had not understood to ask when I first wrote this essay: What does mana whenua mean in this moment? A week after submitting this essay we returned to Waikawa for a long weekend with my family-in-law. The trip had been planned, serendipitously enough, by a sister-in-law who knew nothing of my connections there. I knew we would be close to my people. In fact our cottage was nestled under the hill where my ancestors rest. We went to see them. We passed the marae each day. In the new whale centre and the old museum my great-great-great-grandparents were alive in black and white stills.

I can’t remember who said it first. We could live here. We should live here. Look at the hills. Look at the sea.

It had not seemed like a possibility before. Imagine living in a place where the tupuna are everywhere, we said. Making a real contribution to the marae. Imagine how it would feel to have that much sureness when your feet touch the earth. I could see that one day I may be that person. The young ones will come to visit from the city and think there’s no way they could live in this small nowhere town no matter how beautiful it is. They probably won’t ever live near one of their marae. This is what I thought. But no matter how much you and your whakapapa wander, the homeplace calls.

Tina’s essay appears in

Extraordinary Anywhere: Essays on Place from Aotearoa New Zealand'

Available from Victoria University Press ($40)

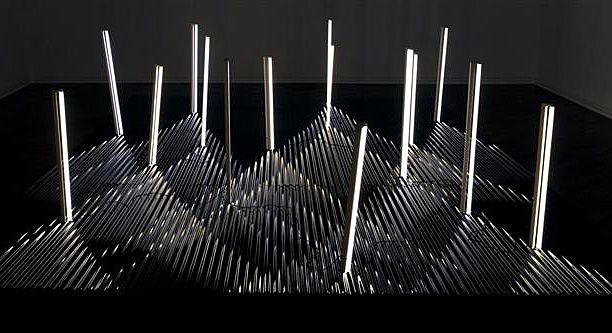

Cover image:

Ralph Hotere and Bill Culbert - Blackwater (1998-99)