By Any Means Necessary

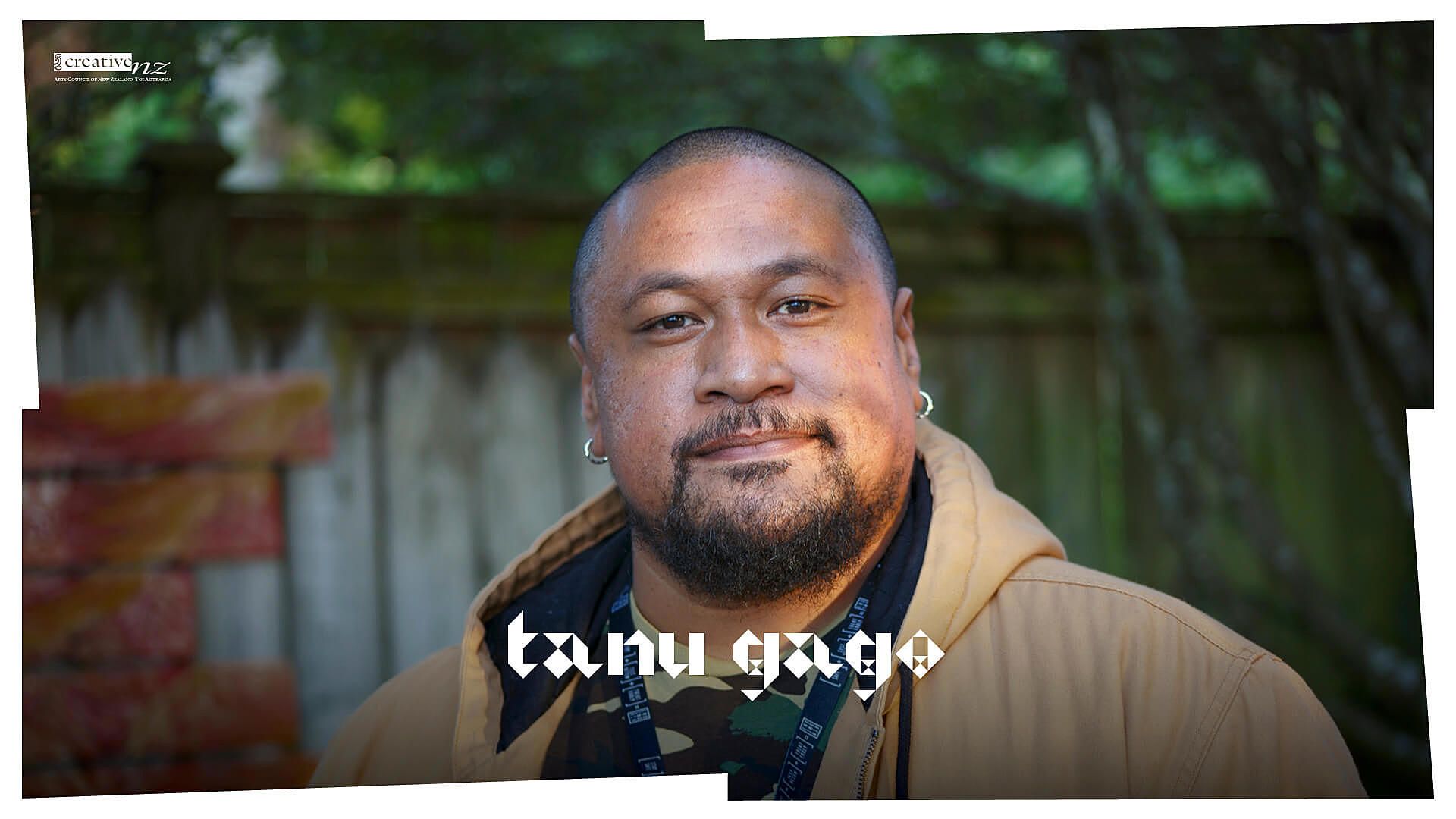

Tanu Gago writes on the legacy of erasure of Pacific Queer communities, the burden of representation and the importance of speaking oneself into existence.

We’re collaborating with Creative New Zealand to bring you the groundbreaking Pacific Arts Legacy Project. Curated by Lana Lopesi as project Editor-in-Chief, it’s a foundational history of Pacific arts in Aotearoa as told from the perspective of the artists who were there.

The timing of this legacy project coinciding with the inaugural Legacy Vogue Ball 2021 feels significant. At least, it does for members of FAFSWAG, who have now made their formal exit from Ballroom Aotearoa. This project seems to speak to some collective desire across our creative sectors to book-end an era, and has a sense of collective rhythm. I am curious to see whether our current cultural need for reflection is also softly masking the urgency to get organised as a community and formalise our cultural data; no doubt prompted by the current global pandemic. Either way, I'm very grateful to have been invited to have a space to consider what legacy is and what it means to me at this moment in time.

I'm part of a middle-child generation, sandwiched between the first wavers – baby boomers – and the current generation of urbanised, ethnic hybrid millennials. We're the generation of kids that grew up in the 90s, watching our older siblings shoulder the cultural burden of remittance, as well as having them deal with a harder version of our parents. We're the generation who didn't have to do things that were expected of most baby boomers, like fighting in a war. We can study weird subjects like art and filmmaking, without disappointing our parents by not wanting to be doctors and lawyers. The idea of counting my legacy in my mid 30s is making me feel like an old bitch, but this historical context for me has a lot to do with unpacking my privilege as a person allowed to choose art as a lifestyle.

We understand what it means to feel genealogically discontinued, as a community surviving in chosen families

The notion of legacy for Queer folk can't be understated, especially as a context of cultural continuity. We understand what it means to feel genealogically discontinued, as a community surviving in chosen families, with Queer legacies time-stamped by history's human-rights timeline, as well as Western societies' legislative milestones, such as homosexual law reform, the AIDS crisis and resulting healthcare policies, civil union and marriage equality. All moments that have shaped the conditions for the wider social acceptance of Queer people to date.

So I'm here for posterity because I'm cognisant of the many ways our Indigenous Queer communities have been left behind. I wanted to write this piece to counter the legacy of erasure, perpetuated and upheld in most historically written accounts of shared Pacific experience by people who didn't bother to see us. It's this very tension that remains the most pronounced characteristic of my practice and subsequent career as an artist and activist; an ongoing act of refusal, to not be erased and to speak myself into existence by any means necessary.

An ongoing act of refusal, to not be erased and to speak myself into existence by any means necessary

I was born in Sāmoa in 1983 and migrated to New Zealand in 1984. I was schooled at Māngere East Primary and Nga Iwi Primary. At intermediate I bounced between Saint Joseph's Boys in Apia, Sāmoa and De La Salle College in South Auckland. I then started my high-school years at Apifo'ou, a Catholic co-ed school in Tongatapu, from 1994 to 1998, completing my last year of high school back in NZ at Māngere College in 1999. I'm an Islander proper – I spent most of childhood on the beach, riding my bicycle through the village and making tapa cloth with my aunt. I've lived in the context of my homeland and my village, Tanugamanono, which I'm named after and where my dad is a Matai. At the time of my birth, my dad was a musician and a carver. He sold his jewellery at the markets during the day and played guitar with a band in the resorts at night. This legacy has always grounded me in my cultural identity, despite living in Aotearoa throughout the majority of the 2000s. I look like my dad, I look like my ancestors, I am undeniably Sāmoan despite having lost the language and not aligning with many of the traditions in my adult life.

I unfortunately didn't inherit my dad's musical talents. Instead I inherited his hands, as someone who could draw. For most of my childhood, drawing was my safe space. It's what I spent most of my time doing, I even ended up at animation school in my early 20s, thinking I wanted to make cartoons like Bro Town, but with more of a dry British wit. I had to do an average of 50 drawings a day, and the technical intricacy of replicating drawn images just to create movement in a frame really chipped away at my desire to draw. Before I knew it, I hated the thing I loved. I figured there were other ways to make a picture move, and so I took up my second creative passion – film.

I'm an Islander proper – I spent most of childhood on the beach, riding my bicycle through the village and making tapa cloth with my aunt

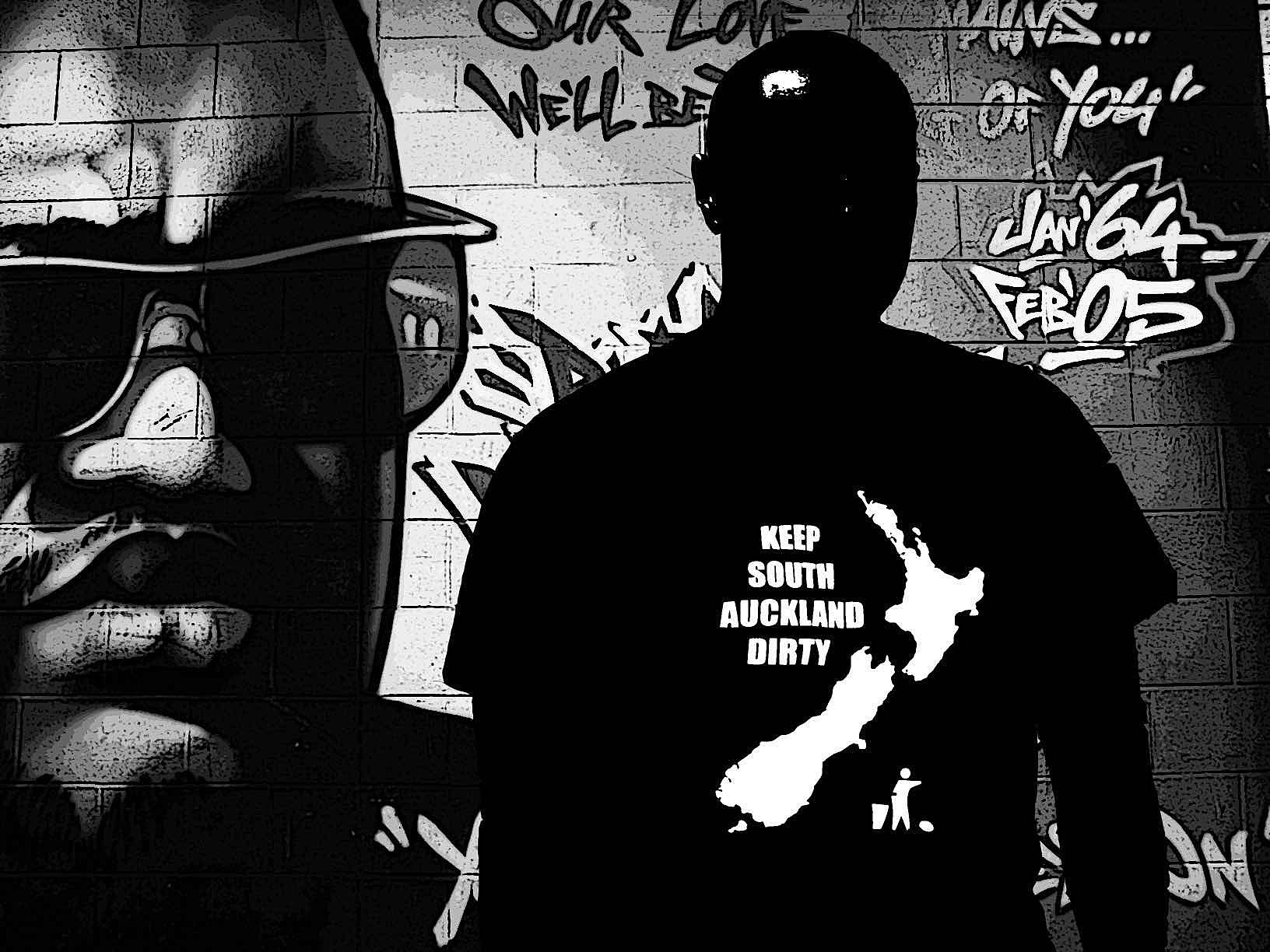

My adopted dad had the worst taste in films. He had boxes of VHS tapes of obscure low-budget actions films with names like Cobra Ninja Squad and Delta Force 5. I watched Total Recall when I was seven, along with James Cameron's Terminator and Predator series. Before I was ten years old, I had watched lots of trash, toxic-masc, muscle-munching, adrenaline films with my dad. He covered my face with his giant hands whenever a rude scene came on, but was all good with me watching acts of glorified cartoon violence. I think this childhood tradition has thematically informed my artistic fixation with masculinity, especially as an openly gay Sāmoan man, who never identified with the types of male characters I was exposed to as a child. Much of my early artworks explore masculinity from my own cultural experience, sometimes built upon the individual experiences of other Pacific men I've photographed or featured in my films.

My journey with art has taught me that being and existing in the contemporary world, as a Pacific person entrenched in the diaspora, is as valid a cultural experience as, say, my dad living the village life in Sāmoa, as he's currently doing today. It has affirmed my cultural identity in ways I don't think many people living in the diaspora are able to process in quite the same way. I've found, for me, it's because I'm actually an immigrant here. That's my family legacy. That uneasy feeling, that identity crisis of connecting to the worlds we occupy here in Aotearoa but still feeling culturally removed because this isn't our land. We can build our homes here, and in most cases we have, but it's not where we're from. Art taught me this. Art has been the only tool in my life to help me understand my own positionality.

YOU LOVE MY FRESH (YLMF), 2010

In 2010, after graduating from film school at United, my friend and independent Pacific curator Ema Tavola curated my first solo exhibition, entitled YOU LOVE MY FRESH (YLMF), at Te Tuhi Centre for the Arts, as part of Manukau Festival of Arts. The artwork which has never been restaged anywhere else since then, was a synchronised, panoramic, three-channel video installation. It was made of three parts. The first was a siva Sāmoa with me and my sister Julie, choreographed by Quincy Filiga to an original recording of the New Zealand national anthem. The second part was a piece of documentary showing the collective practice of community umu making. The final part was large-scale animatics that wove together still photography, typography and animation, set to the instrumental of King Kapisi's 'Reverse Resistance.'

It's interesting to look back over a short period of time and recognise certain motifs in my current practice articulated in that first body of work. To realise how those original points of investigation have become organising principles in my current career pathways. I can now see that my performance with my sister has informed my work in the live performance space. From the formal theatre to the unconventional, my affinity and attraction to staging bodies through narrative action, as well as abstract and bespoke activation, is now something I facilitate for other artists. I can see this embodied in my work as a producer for live performance, spanning the last eight years.

YOU LOVE MY FRESH (YLMF) Animation

The second part of YLMF, a documentary that depicts a community preparing an umu, embodies my social practise and my very personal need for community connection. It's weird to see the roots of my own advocacy and to be able to pinpoint a moment in my career that has politicised my thinking as a maker – to see how this is mirrored by my film-school roots within certain modes of documentary, and how enamoured my art is with capturing real people simply living in their context. These motifs begin to reflect a commitment to deconstruct and reimagine representation over and over, changing and refining with every new image.

Making feature films in this country is a huge financial burden – especially if you want to practice, make mistakes, and generally learn things about the craft – something my film training disabled through a constant and sometimes unnecessary grind of bureaucracy and institutional processes. The final part of YLMF, the animation, clearly demonstrates my obsession with composition, cultural framing and juxtaposition, as well as my frustration with my own training at the Freelance Animation School in 2003. This phase of the work represents, for me, all the weird animated films I've made that repurpose open-source internet footage to create Queer-centred, decolonial, anti-racist, poly-propaganda cartoons – which I keep making for curators who invite me to exhibitions thinking I'll show my collection of old photographic works for the 100th time.

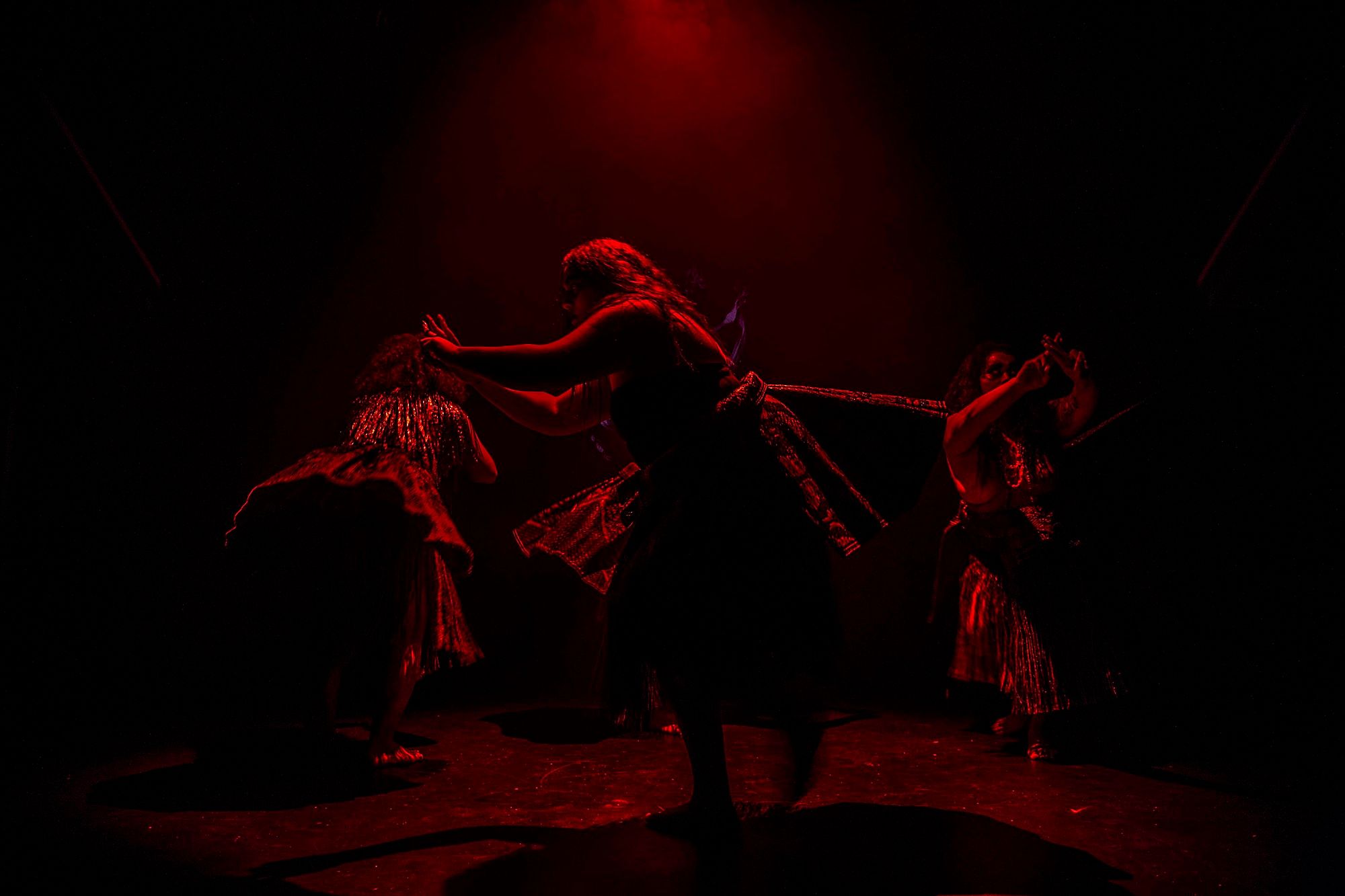

Savage in the Garden Exhibition

Recent works like APPARATUS and SAVAGE IN THE GARDEN, and even the upcoming MATALA project with Hohua Ropate Kurene and Tapuaki Helu, have enabled me to practice a form of visual storytelling that breaks convention. Allowing me, on a personal level, to detach from an otherwise too-expensive and financially inaccessible convention of commercial filmmaking. And yet still get a message across, still tell a story and still represent alternative experiences.

It's easy to see how these three cornerstones of my practice have become more streamlined and synthesised as I've gotten older and as I've moved through my career as an artist. I stopped identifying as a photographer when I realised the thing I'm invested in as a vocation and as a creative mode is actually storytelling. Stories are the one thread the reoccurs throughout these different experiences, and probably the one thread that crosses over into my life away from art as well. For the past eight years the one story I've been most interested in is a shared experience with other artists and other creatives. Which brings me to the FAFSWAG story.

FAFSWAG faaafa, 2018

FAFSWAG is a collective of Queer, Indigenous artists and allies from Tāmaki Makaurau that formed in 2013, off the back of my collaborative solo exhibition at FRESH Gallery Ōtara entitled Avanoa O tama. Avanoa brought together individuals from around South Auckland I had accosted to be part of a series of staged images produced in Southside communities and shot by commercial photographer Vinesh Kumaran. In this project I worked mostly as the artistic and creative director. I was basically using my training as a filmmaker to organise performers and technicians for the staging and production of a digital image – something I had imagined and been meditating on for a year, since my last series Jerry The Fa'afafine.

Jerry The Fa‘afafine, 2010

This mode of operating would ultimately become the fundamental making model for FAFSWAG the collective. A model we would all take turns at refining and improving on over the years. FAFSWAG currently has 12 members, and grew from the social connections created on that project. We had no idea at the time that we were birthing a network of Queer folk that would eventually become key figures within a growing community, and the tuākana of Ballroom Aotearoa.

FAFSWAG's CV looks like a step-by-step glow-up manual for the production and consumption of liberated internet identities. As well as a system map for organising countercultural alternatives to mainstream notions of Pasifika representation, and an example of how to make white art patrons uncomfortable. The collective exists in a constant state of tension between high and low art forms, depending on who you ask.

The contemporary fine-art world continues to erase our artistic merit while simultaneously rewarding us for our participation. This is achieved in the way our individual experiences and identities have been dissolved into a singular homogenised narrative. It's in the way they write about us as characters and not about our art. There is a reductive shorthand used to dissociate our practices from the mainstream by centring or glamourisation our otherness. Curators and fellow artists alike, sometimes unsure of what to say, often describe our work in abstractions, as something amorphous and illusive, and assign our members interchangeable codes, like shapeshifters, disruptors, provocateurs. The art world will also use ballroom and voguing as context or lens to unpack our works, which sometimes don't even reference those worlds.

FAFSWAG Fresh Gallery Otara, 2016

Plurality makes all of these components of a collective social practice more complex, and it only takes a conversation with one of us to be able to see some of the layers of nuance, the intersections and evolving systems. It's taken a long time to understand that the definitions adopted in these spaces are about control, and an attempt by the art world to bring us into some kind of alignment with what is considered to be the status quo or the natural world, and for no other reason than convenience.

The contemporary art world can't decide if we're cheap entertainment or complicated world builders. As a product of art, we're regularly consumed in ways that make it feel like we're both those things and more. Our inexperience in navigating this has led to some hard learnings, some broken relationships, some extreme highs and some peak-bucket-list milestones. We've operated within prolonged and elevated states of hypervisibility. This hasn't always been healthy, and it's pushed some of us into varying levels of survival mode in the past – something we explore with CODESWITCH: Reimagine, Relearn, Recreate, our attempt at collective healing for the 2020 Sydney/Biennale NIRIN.

We know the value of what we do can't be measure in the way we represent a culture that, at large, rejects us and diminishes our voices as Queer Indigenous folk

Our internet profile and canon of lush imagery has sometimes resulted in us being asked to facilitate absurd requests from across the various creative sectors. Some opportunities we dove into headfirst without proper cause for concern. Others we just had to say no to, because our collective goals were becoming distorted. Our current engagement with the collective Ruangrupa curators of Documenta Fifteen and the Lumbung collective of collectives has been a great way of looking into collective power, knowledge sharing and self-determined governance.

As a collective, we've travelled the world and accomplished things that we never set out to do. In some cases, we've had to represent our country, Oceania and the Pacific, as well as Queer Brown folk. Which, if I'm being honest, is a bullshit responsibility when you are trying your absolute hardest to just represent yourself. Some forms of representation we wear with pride and some we resist with absolute disdain. We know the value of what we do can't be measured in the way we represent a culture that, at large, rejects us and diminishes our voices as Queer Indigenous folk. I'm not even sure there are any awards left at this point, to demonstrate our artistic gift to our people. So we've stopped asking for permission and stopped trying to prove anything to them.

FAFSWAG Arts Laureates, 2020

Of all the merits that my art practice demonstrates, I know it will clearly show a passion for Pacific people, a merit for the contemporary skillsets of leadership, and a creative provocation to be fearless in your beliefs, to take up space when there is a social or cultural expectation to shrink yourself. To be ruthlessly, unapologetically your authentic self. To not let colonial traditions frame your voice and worldview as subversive or inferior, and to take creative risks that challenge you and push you beyond the boundaries of your creativity.

*

This piece is published in collaboration with Creative New Zealand as part of the Pacific Arts Legacy Project, an initiative under Creative New Zealand’s Pacific Arts Strategy. Lana Lopesi is Editor-in-Chief of the project.

Series design by Shaun Naufahu, Alt group.

Feature image: Pati Solomona Tyrell.