Creative Thinkers of Christchurch: Bridget McKendry

Brie Sherow talks to Bridget McKendry of Makercrate, forming the first in a series of seven interviews with the creative thinkers of Christchurch.

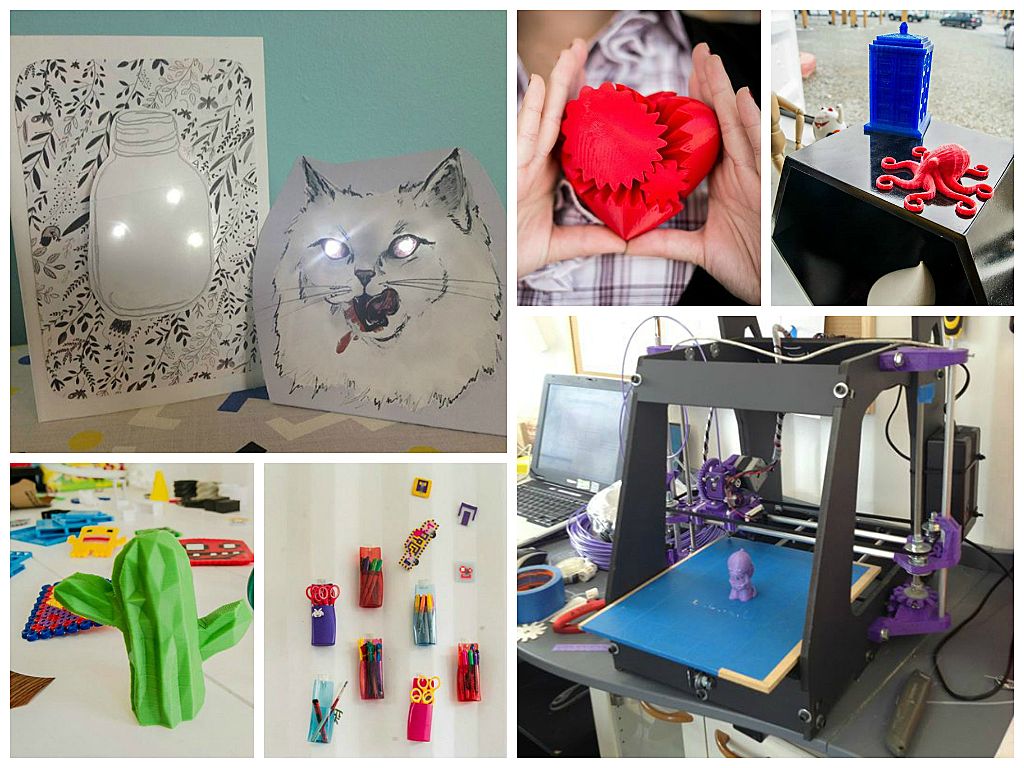

Every time I visit Bridget McKendry’s Makercrate she apologises for the mess, but I hope I never see it clean. Situated in a shipping container and surrounded by rubble, the lab isn’t a replacement for anything that was lost in the earthquakes, but instead is something completely new. Like a cabinet of curiosities, the workspace is an intersection of science, art, and the imagination. In addition to 3D printers and digital cutting machines, Bridget has recently added a machine that turns vector-line drawings into rubber stamps as well as pens that write in conductive ink, allowing you to draw circuitry on paper. Other curiousities - like a knitted prawn and a replica Mondrian painting made from Hama beads - are gifts from her students.

The project has allowed Bridget to work with a range of interesting people: “I’m in my element when we’re all making stuff together, and they’re really excited because they’re doing something that they didn’t even know was possible. I know that feeling, and I love seeing that excitement.” The outward focus is a change from her career as a web designer prior to the quakes, and it’s a shift in energy that has emerged across the city, with new forms of communication emerging from the post-quake atmosphere.

Like the projects being created in the container, the current space for Makercrate is more of a prototype. Eventually there will be a permanent Fab Lab in Christchurch: a prototyping space at the Arts Centre for designers with ideas or for businesses testing new products. Bridget is also working with local libraries to encourage community access. “I think that in the future, makerspaces will be as important as books in libraries.” The process of experimentation is pervasive in Christchurch, with many initiatives that have started small becoming incorporated into the long-term fabric of the city.

This process of experimentation is also a common theme in the children’s classes at Makercrate. “It might not work the first time, and that’s totally normal, but we’ll have a few gos and we’ll get it right through that process.” She says that adults are often hesitant to use the machines but the kids have no fear. “I give them a few parameters and they’re just in there. There’s no stopping them.” She talks of the importance of introducing kids to technology early. She wants them to be literate in 3D-modelling and believes that maker culture will contribute greatly to technology, product design, and engineering. “We don’t know what the world is going to be like in ten years’ time, so we need to equip people for learning in as many different ways as we possibly can, including with our hands.” Similarly, we don’t know what Christchurch will look like in ten years’ time and the best preparation for the city’s future is to experiment as much as possible in the present time.

Bridget doesn’t need much time between idea and action, a trait that helped her create a commercial enterprise out of a hobby in the eighties. She was a teenager then. Outrageous colours and fabrics were in. Mohair with sparkles and beads. Glamour yarn. “I wanted to design one of those big colourful bat-wing dresses that were cool back then, but no one was going to knit it for me.” She learned how to do it herself from local women. Throughout the region, previously successful farms were struggling and women were supplementing their income through knitting. “They were experts. I was so impressed with their technique. It was unusual for a young person to be interested so they were quite happy to help me learn.” She ended up selling her knitted creations to ladies across South Canterbury.

She gets the same excitement from teaching her own classes now. The Fabriko Minimakers course, a 3D fabrication workshop for 10-14 year olds, has just finished its first term. The students went through a design process to create their own products that could potentially be manufactured and sold. Items included a flashing magic wand, a ‘butt pillow’ that lights up when sat on, a light-up dollar-sign ring, and several boss medallions. Bridget says that although the objects they made are a bit silly, the kids learned serious design skills to create them. “Maker culture provides a context for kids to learn things in. Instead of teaching trigonometry or even basic physics or ohms law, it’s far more exciting in the context of an electronics project or 3D modelling. You have to think about measurements and take it out of the digital world and into the real world.”

Her interest in the connections between the digital world and the real world stem from a fascination with the lights and networks in cities. Growing up in rural Canterbury, she relied on overseas fashion magazines for a glimpse at the lights of New York City. “Flamboyant pop stars like Boy George and that eighties club scene had a huge influence on me. It was almost like a fantasy land because I had no way of interacting with it. It might as well have been outer space.” She used the income from her knitting to attend art school in Dunedin. She loved exploring the city and took note of the abstract shapes of the buildings in back alleyways and the networks of the streets. She identifies with the work of artist Piet Mondrian, who references the geometric pathways and rhythms of a city. “Mondrian liked swing dancing, and he loved New York City. When he painted ‘Broadway Boogie Woogie’ that was the layout of the streets and the rhythm of the jazz, and that was a connection that I made quite early on with cities and networks and lights.” Her fascination with streets and networks led to a growing interest in electronic current and flow.

Her early experiments combining electronics and textiles didn’t always work as planned. “I set fire to a lot of fabrics. Back then I didn’t have access to conductive thread or yarn and it was hard for me to make sense of it all with only very basic equipment.” Then she read about Leah Buechley in Make Magazine. Leah was a computer science PhD who was making sewable electronic pieces. She found conductive thread that had previously been used for mending fencing uniforms and she used it to sew electrical circuits and 3D micro-controllers in clothing. Bridget soon found other conductive materials, including a clothing website for people terrified of electro-magnetic radiation. “You can get all sorts of things there: thread, fabrics, even conductive underpants.” With advances in technology, materials became cheaper and more accessible.

Her first e-textile designs were inspired by the night sky she grew up with, with one of her first projects involving embroidering four LEDs to make the Southern Cross. She had some tutorials on Instructables, a website that allows you to document and share your DIY projects, and through that network she was invited to speak and teach at Fab8, the eighth international conference and annual meeting of the MIT-based Fab Lab network, held in Wellington in 2012. It was her first introduction to 3D-printing and the first time that she was able to connect with people in her field from overseas. It was also where she met Richard Fortune, who’d just set up the first NZ-based Fab-Lab in Wellington. “He had this crazy idea to turn a shipping container into a transportable makerspace.” With Carl Pavletich - a Christchurch-based designer interested in fabrication technologies – they transported the Makercrate to Christchurch.

Since then, Bridget’s machines have toured local libraries, tertiary institutions, businesses, craft markets, local schools, TEDx, and the ‘Two-Hour Shop’ as part of the Gap Filler Inconvenience Store. They are also temporarily tenanting the Exchange, a new venue offering production and exhibition space for emerging creative enterprises. Bridget’s main focus at the moment is teaching people about the technologies and how they can be applied.

Although Makercrate is a transportable structure that could be located anywhere, Bridget sees it being most valuable in Christchurch. Many of the crate’s visitors are young tourists who’ve heard about the transitional projects in Christchurch and are eager to experience them. “It’s so refreshing,” she exclaims, “because when you’re a local you’re quite over the earthquakes and the floods. It’s easy to get jaded. But then overseas designers and architects come and they’re telling us how awesome this really is.”

The ultimate aim for Makercrate is to support a broad spectrum of creative industries. “Innovation grows in unusual places,” Bridget comments, “cheap places where artists and small start-ups can move in and grow organically.” Christchurch, more than anything, is an exciting testament to this.

Bridget at FESTA:

Light Up Your Life

Also in this series:

Reconstruction and Renaissance

Audrey Baldwin

Amiria Kiddle