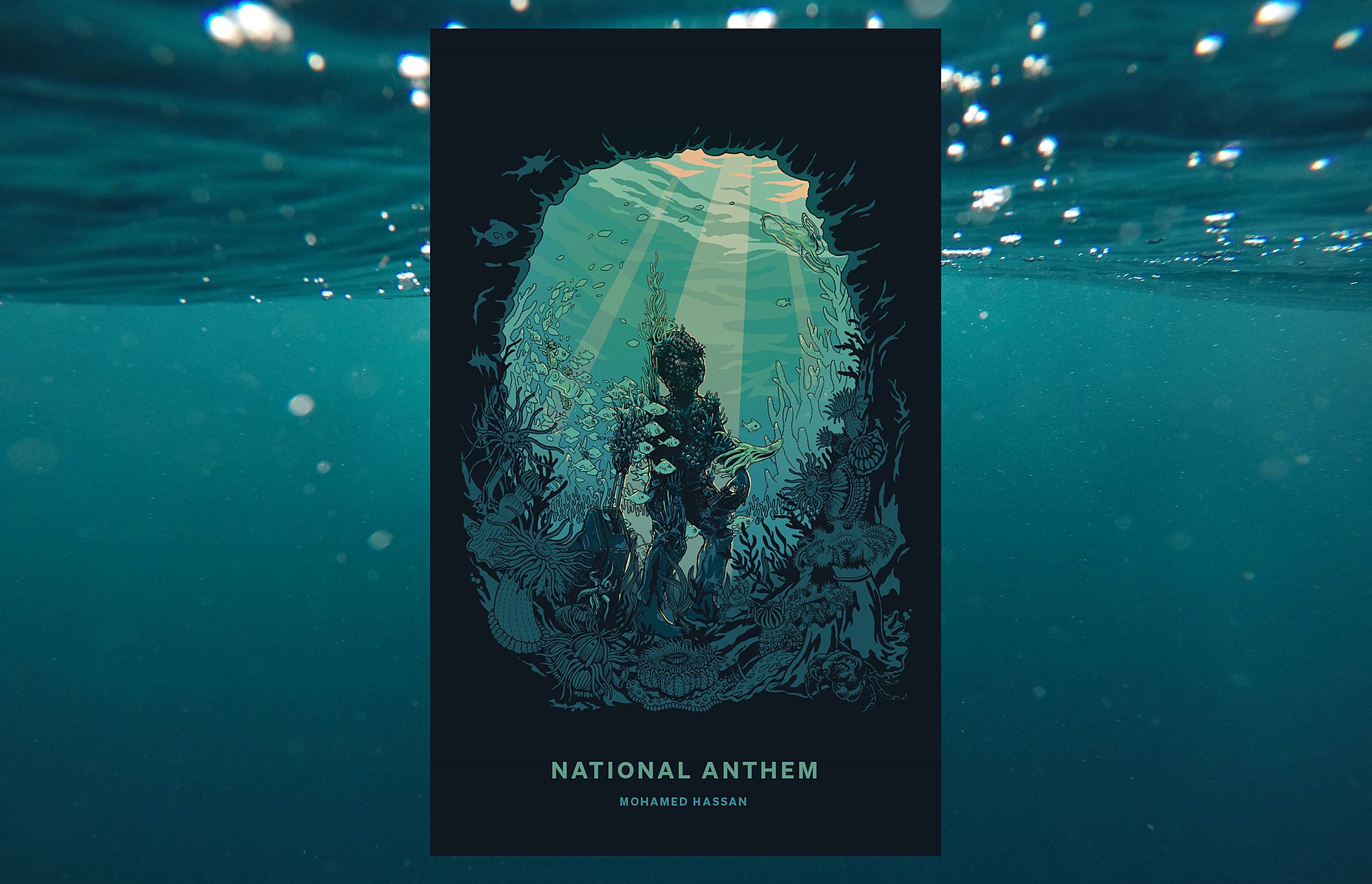

Breathing | A Country Called Life: On Mohamed Hassan’s National Anthem

On country, memory and finding respite in National Anthem.

*

What is a country but a life sentence? – Ocean Vuong

*

“I can’t breathe”, James Baldwin is said to have once remarked, explaining his self-exile: “I have to look from outside”. Overwhelmed and constricted by the worst excesses of American apartheid, its everyday presence an intractable stranglehold, Baldwin spent much of his adult life in other countries. One of those places was Turkey, where he lived on and off for almost a decade, and where he produced a significant chunk of his work, including the novel Another Country. In a place that seemed, in so many ways, to be in-between – to be in-between worlds – Baldwin found respite when it seemed to him that the “entire world is no longer livable”. One sees things “from a distance”, he explained, “from another place, from another country”.

Mohamed Hassan’s National Anthem is a poetry collection as beautiful as it is poignant, and in it we find the meditations of one who, much like Baldwin, seems to always write from a distance: from another country. This is a collection that at one and the same time seems motivated and vexed by a palpable experience of displacement, its antiphonic call or appeal issuing both from and towards the elsewhere. In this way it begins and ends with the other side of whatever is already here.

The other side: this, it seems to me, is the most persistent concern of the book. After all, what is a country, etymologically speaking, if not what lies beyond, in the distance? A country, in an important sense, is always ‘another’ country. It sits there, beyond our reach but ‘before’ our eyes. It precedes us wherever we are, but it also lies opposite, opposing and refusing us, at every turn.

After all, what is a country, etymologically speaking, if not what lies beyond, in the distance?

Haunting and refusal: the book is an account of ‘country’ as a name for this double valence by which many of us are contoured and contorted, our bodies becoming its living archive. It breaks out in sweat, trailing on the skin of “guilt a homeland I have / sewn onto my palms / but can’t dream in hold”; it intrudes as a “daydream”, and bulges into “a tumored mother tongue / trembling over the weight / of expectation”; it burrows deep into the bone, “a dream of one day going back home for good / it’s a tiny dream”, like a cyst pushing up against the spine, which “hurts every once in a while / when I hear my grandma’s voice or listen to a Fouad song”. Also like a cyst, the psycho-somatic traces of country stick: “you’re kinda stuck with them for life”, consigned to live them out in “recurring dreams”, that “hang around with the ghosts / sticking to the shelves”. They make a home of us even as we are refused one of our own.

Or, put differently, it’s because it has made a home in us that country makes home impossible. The exile is at the mercy of memory’s wild and whimsical associations, having but to “pass an open sewer in Brixton markets / and I am back outside my grandfather’s / flat, the jasmine trees croaking beneath”. Memory becomes a cruel, capricious, and unrelenting overseer, exercising its will as injunction rather than as volition. It mocks us, gnawing at one in home’s innermost reverberations like lyrics impossible to dislodge:

Memory of home would find us, even if forgetting was possible, and in it are its taunting reminders of why home must remain in memory, at a distance: “the jasmine trees croaking beneath / the circus balloon, watching my parents / fall in love, the secret police arrest my cousin”. Diaspora makes of every memory, home, and memory of home, a scene of loss.

To remember is never to reminisce, and should you be tempted, there is always a ready refrain: “my uncle tells me I’ve romanticised Egypt / he can’t understand why I’m not content / with Western opportunities kids my age / fling themselves into the open sea just to taste”. In her own collection of poetry, Schizophrene, Bhanu Kapil renders the condition of post-partition South Asian diasporas as akin to psychosis:

“It is psychotic to draw a line between two places.

It is psychotic to go.

It is psychotic to look.

Psychotic to live in a different country forever.

Psychotic to lose something forever.

The compelling conviction that something has been lost is psychotic.

What is the experience of country but this interminable, life-long psychosis, which makes of every sign and sound of it, such as a national anthem, an occasion for at once feeling “the same pang of longing / the same pang of disgust”? It is an affliction compounded by every iteration of country, its past memories and present experiences collaborating to deepen the malaise:

All my life I’ve wanted to fit in and never have

Like a hippopotamus at an office Christmas party

Who doesn’t drink for religious reasons

…

I am bored out of my existence

…

Boredom has paved me into the darkest places

It is more satisfying to fantasise

Unspeakable violence against myself and others

Than fend this gravity alone

How to be content, when country’s losses transmogrify contentment into a sheer, lonely, and psychotic boredom? If home can only be experienced at a distance, as distance, then being at home in the world is only possible “if you hold everyone at arm’s length”.

*

What is a country but a boundless sentence, a life? – Vuong

*

At length, and at a distance: what might it be to come to terms with this as the measure of home; as the measure of life? If Mohamed’s is a meditation on country as the agony of distance, its intent is not to close it, but to dwell and eke out a living in it. This vitality, after all, is a gift bequeathed by those who measured our own lives in the immeasurable distances they covered, etching and fashioning home out of the nothingness of space itself. A father’s solemnity and a mother’s prayer, imploring one in a distant land to come home, are occasions to remember that “migration is its own form / of social isolation / an ocean sits between you and everyone else / a distance you must swim every day / just to make it to the starting line”; that “home / by any other name / is a quarantine / you have chosen / is a field of dandelions / flung together / learning to grow”.

Here, there is a sobering reminder that migration is return and repetition, displacement doubled and multiplied across generations over the course of which diaspora becomes a hereditary condition. But here there is also something else: a reminder that migration is extension and expansion; is lifespan, life outrunning itself in the constant spanning of space through lineage. And isn’t this simply characteristic of any life worthy of its name? As Georges Canguilhem once put it, the living is simply that which extends itself, frolicking in its own enumeration.

Enumerating and enunciating itself into existence, the living counts and names the ground on which it walks, stretching itself out in words: words that are weightless but that carry the weight of our worlds in them. Of migrant lovers torn apart by ‘country’ and failed by the promises of documentation, Mohamed recounts: “we’ve been stretching words like this / four years making bridges out of paper / folded like passports / like sailboats / floating into the sky / have you ever tried to fold / your heart into an envelope?”

Here, there is a sobering reminder that migration is return and repetition

Like all books, then, this is one vexed with the problem of putting felt things into words; of touching the texture of life through text. But of course, this is not just a book but a transcript, a record; its original motivation having been to voice things, not write them. Reading the words, one is reminded with some sadness that they are meant to be heard, not read. What do we lose when we can’t hear life’s will to expand; when we can’t experience the living and its extension as sonority?

To this question we’d find an answer in Mohamed’s own story of creation; a history of the universe as heard through the ears of those dispossessed of voice:

When Umm Kalthoum shakes

Her handkerchief wildly

In the air it’s rude

Not to stare she drinks

Her Arabic like sex

Or a violin string licking

Its bow from chin to elbow

…

Hold out your open hands

For deliverance, the moans

On the live recordings

From 1940s audience

Disciples are every part

The composition

This woman

A planet

This history

Orbiting with her

Our hands flailing

In the glory of an earth

Created to birth her millions

Of years of evolution leading to

The moment the orchestra quiets

And a messenger speaks her first ahh آاه

Swelling like a red dwarf through time

And space

Here is the expanse of life through time and space in the form of voice, a sonority that a national anthem (al-nashīd al-waṭanī) can only grasp at. But the distinction is a false one, and Mohamed’s book masterfully gives the lie to it, claiming back a medium that is so often an occasion for both ‘longing’ and ‘disgust’. In his Introduction to Arab Poetics,Adonis, that giant of modern Arabic literature, reminds us: “If we go back to the root of the word ‘song’ (nashīd) in Arabic, we see that it means voice’, the most faithful manifestation of which is spoken poetry.” “The voice in this poetry”, Adonis continues,

… was the breath of life – ‘body music’. It was both speech and something which went beyond speech. It conveyed speech and also that which written speech in particular is incapable of conveying ... When we hear speech in the form of song, we do not hear the individual words but the being uttering them: we hear what goes beyond the body towards the expanses of the soul. The signifier is no longer an isolated word, but a word bound to a voice, a music-word, a song-word. It is not merely an indication of a certain meaning, but an energy replete with signs, the self transformed into speech-song, life in the form of language.

Life in the form of language, moving us towards the farthest expanses of the soul, al-nashīd is simply that kind of respite; that respiration, which occurs “in the songs I breathe to”, and it can only ever hurt. In what other moments do our lungs find air anew, as if for the first time, if not in those pangs of longing and disgust, and in the throes of psychosis?

“People talk about John Lennon like he was God”, Mohamed writes (in a tone I relish imagining as full of an appropriately callous contempt), “but he never spoke to me”. Someone like Lennon, that symbol of a class of cosmopolitan, globe-trotting elites, who could imagine there being no countries, and who could then put this to song, can hardly begin to imagine the breathlessness of life at a distance; to experience country in all its life-giving pangs and aches; to “love a country that does / not love you back / that no longer has a place for you / in its dazzling future that would trap / you in its claws and stigmata you a traitor”. Indeed, “what Beatles song could ever / make me feel that way”.

John Lennon couldn’t be God, because the latter, as Rainer Rilke taught us, is one who speaks to each of us, enjoining us to go to the very limits of our longing; to let everything happen to us, both beauty and terror, and reminds us that nearby is a country – a country called life.

*

If we are lucky, the end of the sentence is where we might begin – Vuong

*

“Everything is borrowed and owed, even walking on this earth”. So begins National Anthem, giving through her own words a moving homage to Mohamed’s grandmother. In a way, this line sutures the entirety of the book, its delicate point threading its way through the poems until, finally, it cuts off where the collection ends, with the author narrating his retrieval of what was lost: his own name, and his own voice. Having been once taken, these are stolen back by one to whom they are owed.

If this collection begins and ends with an-other side, it also begins and ends with an other. Each part is summoned by the injunctions and interrogations of that recognisably malicious interlocutor, and in turn summons its reader in the response, which is never just a response since it has no address. “When they ask you where you are (really) from / Tell them you are an unrequited pilgrim”; “When they tell you to go back to where you came from / Tell them about the moon”; “When they ask you why you speak so well for an immigrant / Tell them about your grandmother’s laugh” / “When they tell you they are sorry / The muazzen calls you to pray”. The response is also a refusal, and a reminder. The words, no sooner have they begun with it, at once displace the address of race, tracking their own path and carrying us elsewhere in their flight. At every turn, we are turned away from interpellation, encouraged not to give away our self in giving response, and reminded that in its innermost part, there is an other: someone or something else; that otherwise call (or laughter, or lament) that beckons us still.

These formative exchanges, which spark every set of poems, are then part of the symbolic economy of the book, wherein one partakes by taking back what was stolen, and giving it on, without giving it up. This is poetry, after all, and poetry, as Mary Ruefle notes, puts its faith “in obscurity, in secretiveness, in incantations, in spells that must at once invoke and protect, tell the secret and keep it”. An occult practice that adamantly, militanty refuses to give up on the scene of loss, it insists on transforming it into a scene of plenitude; of gifting. Where diaspora might launch us into that ‘psychotic’ spiral, turning memory into a curse, it can also conjure magic. Mohamed shares a trick: “if I close my eyes and twist my fingers in the air / my life is a highlight reel / I rewind the best parts / colour grade the madness / pay homage to the greats / my mistakes look beautiful in slow motion / my regrets nonchalant with a laughing track”.

No wonder then that country must be treasured, even as it must be displaced. Mahmoud Darwish said as much when he wrote these lines, in a tribute to that singular thinker of exile, Edward Said:

He loves a country and he leaves

[is the impossible far off?]

He loves leaving to things unknown

He loves a country and he leaves:

I am what I am and shall be.

I shall choose my place by myself,

And choose my exile. My exile, the backdrop

To an epic scene. I defend

The poet’s need for memories and tomorrow,

I defend country and exile

The poet’s need for memories is our own, and poetry is its best defence in a world that threatens it with oblivion. How would voice, life as sonority, resonate otherwise? It is only through plunging into the depths of country’s memory that one can re-emerge with that primal sound, “that first ahh” birthing speech where there was stutter; lending itself to poetry so that poetry can lend itself where there is not simply silence, but something else: that which Toni Morrison describes as “unspeakable things unspoken”.

The poet can preserve and transform memory because, unlike the reporter, their task is not to showcase trauma but to testify to it. As Darwish himself put it, whereas the camera exposes the wound, the poem can host loss. It would be difficult to imagine the possibility of this collection without the commitments of one who strives to take note of things that go unnoticed; who mourns our collective inability to “notice the worlds / we are swallowing”. But he is also beholden to the perpetrators of this cosmological autophagy, all too aware of his role as “a false profit sent by the gods / to birth the world in their image”. Here, the poet comes to the rescue of the journalist. Adonis, again, on the task of the poetry at the dawn of its birth as song:

It was his duty to give to the collective, to the everyday moral and ethical existence of the group, a unique image of itself in a unique poetic language. In doing this the poet was not expressing himself as much as he was expressing the group, or rather he expressed himself only through expressing the group. He was their singing witness ...

Poetry keeps watch over that blurry line between witnessing and spectatorship, its words an incandescent talisman that wards off the gaze of others, so that we can dare to look at the wound and see it on our own terms and through our own eyes. To give an image of the world which is unique, which is opaque to all but those who suffered the loss of their world and suffered the loss of their place in the world, is to give back in this image nothing less than the world itself.

To bear witness to country and loss (and is there a difference?); “to pledge / a steady voice” in singing their praises, is to insist on beginnings, exactly where things end. Or perhaps, it is to insist on endings, so that things can begin, again. For what else is there to do when silent and whispered prayers fail us; like “to’borny / the prayer to never have to bury the one you love / that they should be the one to dig your grave / and plant flowers and live with the memory”? When prayer fails, poetry teaches us to live and breathe despite “a love that sears into your lungs and lingers / if you draw the short straw and not die first”. After all, ‘poetry’, as Franco Berardi writes, “has to prepare our lungs to breathe at the rhythm of death”.

Everything is borrowed and owed, even the earth on which we walk; even the air on which we draw. To be the singing witness is to strive, even as the world seems ever more unlivable, to see things differently, not to say “my people my people / look at the mess we have made”, but to say, look again; look again and see that “maybe an abyss of delicate chaos / is just a sign of life … is a season breathing again … a life worth ending and beginning”. It is to find yourself, as the poet does, in another country, a place like Turkey which, in all its unfamiliarity, in all its unlikeness to and distance from country, gives him air to breathe, at the very moment when loss has robbed his lungs clean. It is to accept this gift, and in turn to offer in its memory a place in which others can find respite, “like a home or a book you can see yourself / inside of”.