Borrowed Lungs: My Life as a Conscript

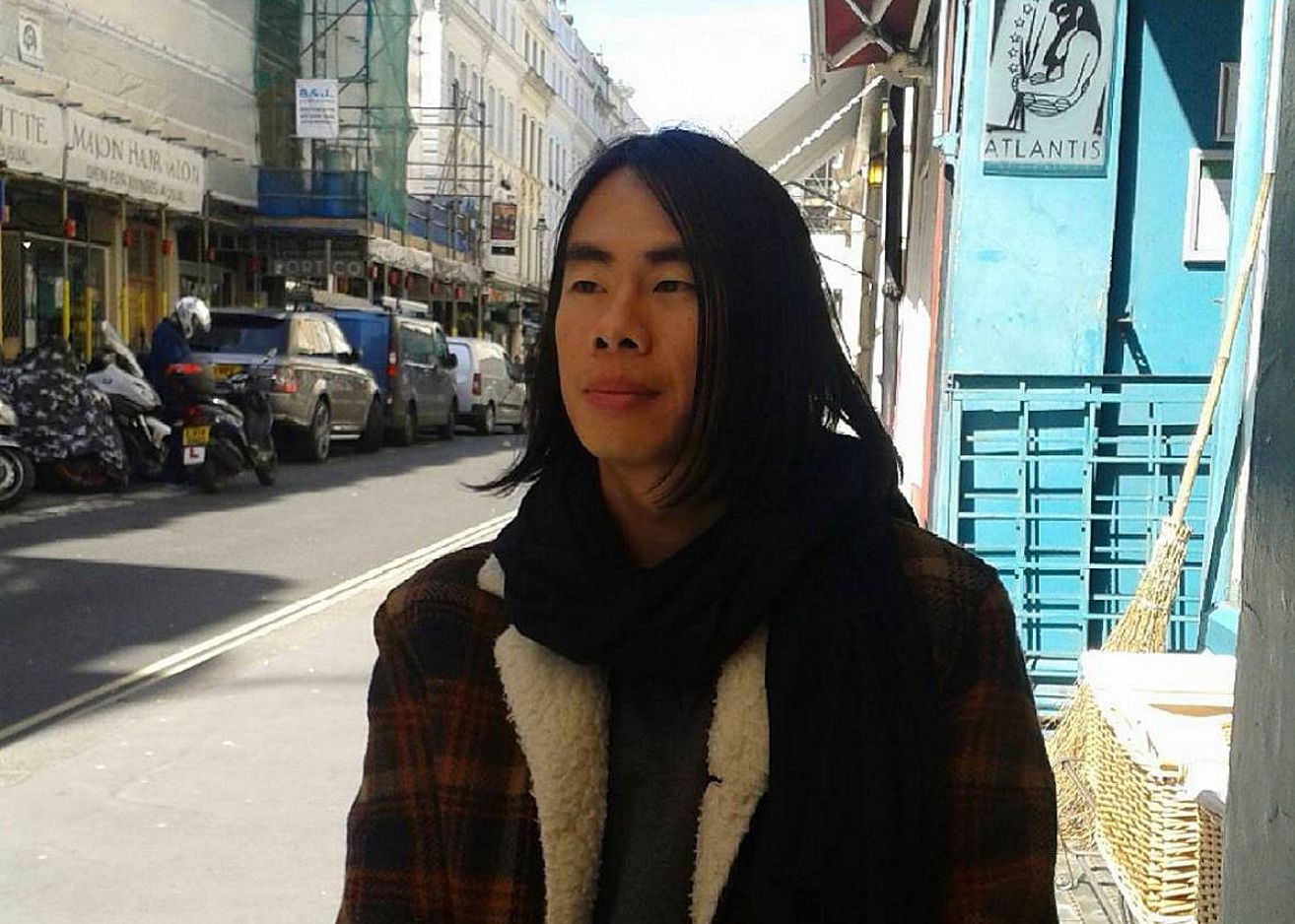

In 2007, poet Greg Kan was sent from the country he'd grown up in to a country he scarcely remembered for two years of military service. Here, he recounts the experience for the first time.

In 2007, poet Greg Kan was sent from the country he'd grown up in to a country he scarcely remembered for two years of military service. Here, he recounts the experience for the first time.

In 2001, my parents cobbled together $75,000 that, simultaneously, allowed our migration to New Zealand, and would eventually bond me to 2 years of national service in Singapore. Six years later, when the time came, there was no outward trace of it. No government-officiated letter or phone call reached the house in Saint Johns where I lived with my parents. My friends in Auckland knew I was about to leave, although it must have been difficult for them to understand its conditions. Some remarked on the impossibility of the decision I’d made. There was no decision, but rather a play of forces – political, economic, legal.

In Singapore, it is compulsory for males who have reached 18 years of age to enrol in national service. The term is 22 or 24 months, depending on one’s physical fitness on enrolment. I was to serve in the Armed Forces, as part of its conscripted military, for 24 months. My family paid a bond because we wished to live elsewhere; but I was deemed to have lived in Singapore long enough to have to return. Refusal entailed a summary trial or court martial in the military justice system, on charge of being AWOL. In short, I would be arrested if I ever landed in Changi airport – even in transit. My return was a ventriloquism emergent of a force-field, an inexorable cultural response and not a decision. Around the end of the last year of my Auckland high school education, I packed my suitcase, boarded a plane, and was given my first real lesson in power.

In nine strokes, the first beginning from my right temple, I no longer had hair. I was moved from the large room we’d started in to another large room of shaven heads. I found myself unable to recognize anyone I’d met in the first. We put on grey training singlets. We were told how to arrange the items in our lockers for inspections. Fifteen strangers slept in one room that night. I thought that we all had the same face, that we all had the same eyes.

As recruits during the first three months of service, we were told where to go and what to do (i.e. herded) by section instructors, who bore a sergeant rank. Their orders were legitimised by commissioned officers – the “fathers” above our non-commissioned “mothers”. Intensity plays a fundamental role in the formation of memory. As with childhood, I remember the ways we were punished more easily than the ways we were actually trained.

Sometimes, in seemingly arbitrary fashion, we were given impossible timings to meet. “Change Parade”, for example, would proceed as follows: thirty people stampede back upstairs, to fall-in again in completely different gears. You’re late. Change into your Smart-4 (neatly folded and pressed camouflage fatigues and parade boots). Your ten minutes started six minutes ago. You’re late. Change into your PT kit (singlet, running shorts and shoes). You’re late. Change into your admin attire ... And so on.

Against the already-overwhelming tropical heat and humidity, some would risk donning their camouflage fatigues over their singlets, trying to save seconds. Others would arrive downstairs in the entirely wrong attire. And so on. I would arrive downstairs to find the rest of the platoon already neatly arranged – forty-five degrees to the left, in push-up position.

For failing bunk inspections, we were banned from sleeping on our beds during the day, so that we were forced to preserve the cleanliness of the floors if we wanted to nap. In our first extended period of training in the jungle, we performed back-crawls, rifles held above our chests, through our latrine area. The final day of the 22 or 24 months of national service is called “ORD” or Operational Readiness Day. I never once in the army considered my operational readiness. I don’t think many of us did. I just wanted to get through.

In basic training I attracted the term “Jiak Kan Tang”, or “Kan Tang” for short, which roughly translates as “potato eater”. While on its surface, the designation was a mockery of my Anglophone accent, the act of distancing ran deeper. My section instructor once told me that I was arrogant, and that I felt I was better than the others, even though I constantly felt frail and incapable. At the time I didn’t realise that my accent bore class, as well as cultural, significations. I did come from an upper middle-class background, although my family lost most of its money during the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. And we did have enough money to move to New Zealand. Yet while I felt different – certainly after discovering the way I spoke was marked by a conflation with dietary habit – I never felt better than the others. I was often clumsy. I was always dazed. It took me a while to grasp lessons, especially when I was running around with the dual weights of helmet and rifle. (And it was true what instructors said – you were dumber the instant you put on a helmet.) So the prejudice confused me, and while it largely fell away among the other recruits as they got to know me better, my section instructor persisted in his. Shaking his head – after witnessing a particularly mazy run of mine through the underbrush that probably would have guaranteed my annihilation by friendly fire in real combat conditions – he told me that “someone like you will never get this”. It was difficult to feel foreign in Singapore as well as New Zealand. And it was difficult to return to find Singapore a more foreign place than New Zealand.

Filling out an expression-of-interest form at the end of basic training (which lasted 3 months), I marked “Yes” to be considered for command school. There were a number of reasons to compete for a place in officer cadet school (the “higher” of two possibilities for the remainder of my service - the other was a place in a course to become a non-commissioned officer). Commissioned officers received twice as much of an allowance. They could have better food at the officers’ mess, and cheap beer. They had proper rooms and bathrooms. And commissioned officers were the ones who had power over the others.

It is obvious to me now that this was the moment where I decided to gain the most power to guarantee the most protection. It wasn’t so much one particular event – say, the time I watched someone forced to run around a building yelling “I am a stupid bird!” over and over, or any other senseless dehumanization in the name of regimentation I may have experienced – but rather the knowledge that I could be subject to such an event at any given time, for any reason real or contrived. In general, I wanted to escape. By this point my otherness had also become firmly ingrained in my psyche; I thought that perhaps by joining the command structure I could transcend my difference.

I got to officer cadet school, eventually, after being funnelled through a regime of assessments measuring my physical fitness, combat fitness, command and control, emotional stability and tactical awareness and knowledge. The office cadet course was a 9-month extension of this. I remember trying to decide where to send my machine-gun team while my instructor struck me repeatedly in the helmet and screamed at me. I laughed a lot in these times. Short, sharp bursts – not in amusement, but to expel the moment’s sheer excess. Crying wouldn’t have been quick enough.

*

Beside a large river in Brunei, I tore the head off a quail, as I was instructed. I was on an 11-day jungle confidence course, one of the more brutal moments of officer cadet school. Its liver was reddish-brown, with no white spots, which meant the quail should have been healthy enough to eat, but I threw it into the river as soon as the instructors left on their boats. The smell of blood on my hands ran on for days. The first sound of rain reaching the jungle canopy was always far away enough for me to hope it was the wind. I heard later that one of my platoon mates lost his machete in the rising mud. In the jungle I came to know a darkness full of noise, none of which I could recognize.

It had been four or five months since my commissioning. An officer is recognized by the display of rank on the shoulder, instead of on the arm. I grew accustomed to soldiers falling silent when I passed them in hallways, or in forests, on parade grounds, or in offices. You can follow the trajectory of a body as it passes through one knot of forces to the next. I had been given rank, but I had been given no power. With each successive command I issued, I realized that I was nowhere nearer to claiming individual expression, let alone control. I became aware of myself as a mere body positioned to channel an imperative from a larger, regularizing network of forces. It was agency, but it was an impersonal agency. For the moment, it had borrowed a pair of lips.

Part of the reconnaissance course we conducted involved resistance-to-interrogation training. The trainees were captured. Their weapons and equipment were taken away. They were cable-tied and blindfolded. The blindfolds had numbers on them. The trainees were addressed from then on by the number on the blindfold. They were gathered in a single area bounded by concertina wire. They were placed in high-stress positions which involved various kneels and squats, whose specifically inventive contortions ensured a significant intensification of pain over the 10 or 12 hours they were forced to hold them. Many of the trainees fell asleep in these positions, having already been carrying out missions for the past 3 or 4 days. They were jarred awake by instructions to change position screamed at them through a loudhailer. Individuals were led to rooms where their blindfolds were removed and they were interrogated over maps for information. I have been on both sides of the blindfold. I have never seen so many bodies contained and processed this way.

I remember that when I was in primary school, there were pencil sharpeners that could be bought cheaply from the school stationery store. These had a small plastic container attached that held pencil shavings. Most of us used these containers to house our spiders. I had a glass jar with a magnifying lid to keep mine in. The spiders we found were all more or less the same size, and I always thought they had the same face. The original intention was for them to fight and kill each other, but we struggled just to keep them alive. Even when we managed to put two of them together they often seemed uninterested in fighting. Made faceless, individual differences erased, reduced to bodies, further reduced to body parts (trigger-hand, aiming-eye, crouching-legs), all for easy manipulation and mobilization in a theatre of war.

One day after receiving my civilian papers and walking out of camp with my gear bag for the last time, I was back in New Zealand and back in school. It was already the second week of semester. Was it weird to find myself sitting beside fresh-faced 18 year-olds in a lecture theatre at Auckland University, hours later and half a world away? Not as weird as I expected. The university is also a processing centre for bodies, to prepare them for the theatre of work. I sat with about four hundred others, neatly arranged in a lecture hall often jokingly referred to as “The Fridge.”

I wish I were better able, at this point in my life, to trace the changes that followed me out of the army, in my return to civilian life. Most of those are still indeterminate, and require further dragging through the mush and opacity of experience. But there are little strangenesses. When walking down a dirt track at night I am sometimes confused about which country I’m in. All dirt tracks feel the same to me, at night. I like leaving rooms more than I do entering them. I am never late, unless I want to be. I feel safe in forests, whose chaotic ecologies of overcoming and displacement elude all apparatus of capture.