Borders, Divisions and the Space Between: Three Writers on Borders

Fair Borders? editor David Hall talks about borders and their agonies with Kapka Kassabova, Lana Lopesi and Arama Rata.

Fair Borders? editor David Hall talks about borders and their agonies with Kapka Kassabova, Lana Lopesi and Arama Rata.

“It’s true, honey. The only good thing about a border is that you can cross it.”

– Emel in Border: A Journey to the Edge of Europe.

So what’s the point of a border then? Obviously, not not to be crossed. That’s what’s good about borders, apparently. What’s bad about borders – and especially the borders that we live with today – is that certain kinds of people, for a host of senseless or wicked reasons, aren’t allowed to cross them at all. Or only allowed to cross on terms which would make their lives miserable. That’s what’s bad about borders: they can be used as instruments of cruelty.

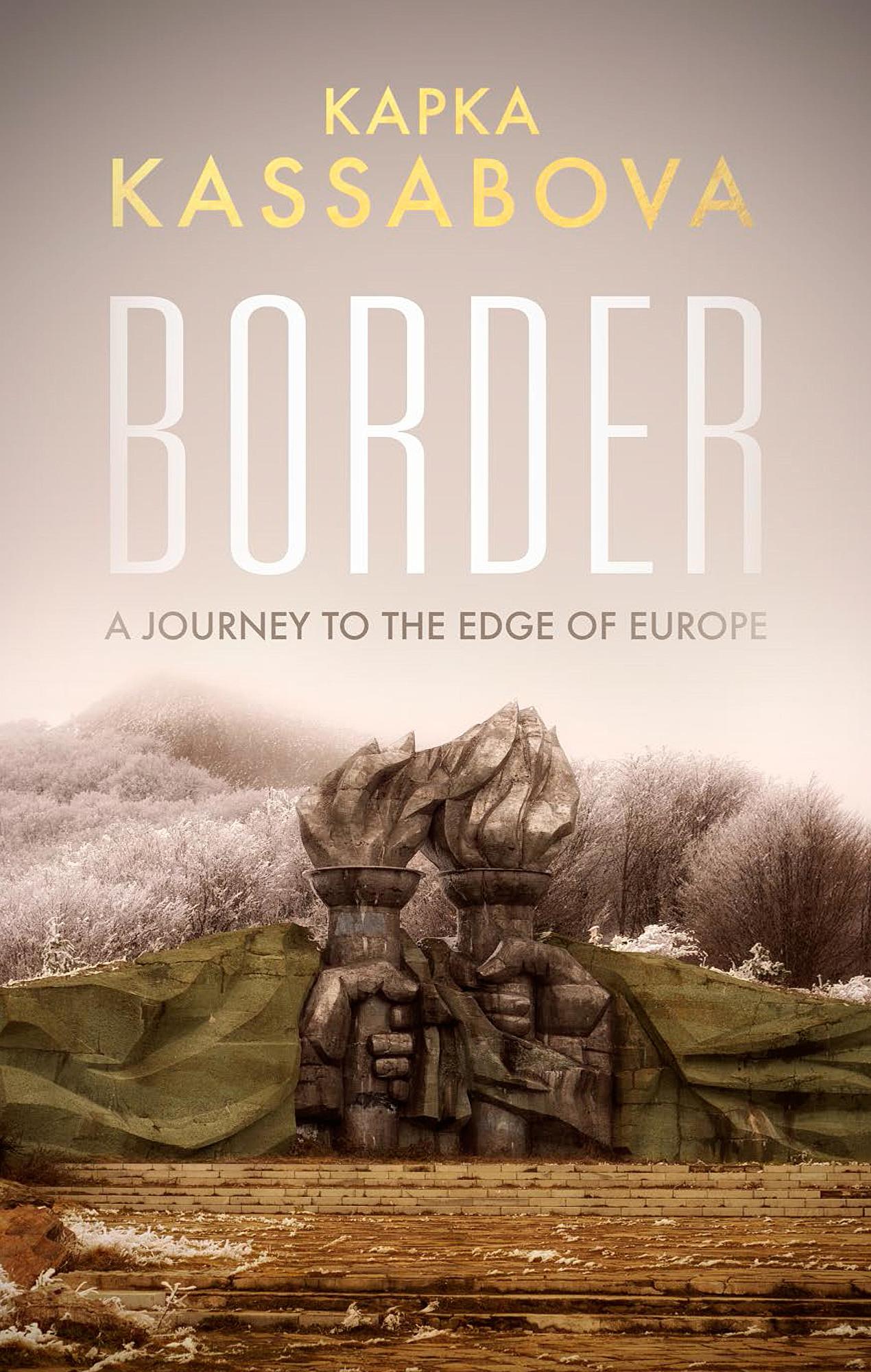

That potential is abundantly clear in Kapka Kassabova’s 2017 book Border: A Journey to the Edge of Europe. Born in Bulgaria, resident for many years in Aotearoa New Zealand and now based in Scotland, Kapka’s haunting and intricate travelogue is about Bulgaria’s southern border, which separates the post-communist country from Turkey and Greece, tracking through the Strandja ranges in the east to the Rhodope Mountains in the west.

“One of the fascinating things about that border,” she tells me, “is that it’s a total margin, a liminal space: forgotten, neglected, isolated in the midst of this wilderness. At the same time, it was a frontline of the Cold War. The Cold War took place – in terms of deadliness – in hidden places like this border zone. That’s where people got shot and buried in unmarked graves trying to cross. That’s also where young army recruits shot themselves. These are the true stories of the Cold War...these unwritten stories.”

At the time, Bulgaria had a reputation as the back door of the Eastern Bloc, a chance to reach the West by first travelling further east through the Balkans, then over the southern Bulgarian border into Turkey or Greece. It was a geographical boundary, but also a political boundary, separating the Warsaw Pact from NATO. Some succeeded in crossing unauthorised. But others died trying. Still others were captured, often beaten or injured before being diverted into prison. Bulgaria’s Communist regime called this border The Installation (Saorajenieto), consisting not only of walls and fences, but also false fences to confuse would-be escapees. The feeling of freedom could be a fatal giveaway.

Kapka says, “We think of the border as these binary things: us and them, this side and that side. But...there are multiple afflictions within the border zone, rather than a nice clean delineation. It becomes a labyrinthine world of paranoia, mistrust, ignorance and rumours. To this day, people whisper about what happened 40 years ago in the border zone. It’s still not safe.”

Borders often appear to be essentially paradoxical. For example, a border is not only a division between two places but also a place in and of itself. People live on borders and this has its own predicaments, which Kapka captures in her stories of “the border people,” like Emel – who provided the epigraph above – whose daily life involves shuttling legally between the border cities of Edirne, Turkey, and Svilengrad, Bulgaria. Or Ziko the smuggler, who, like his father before him, crosses clandestinely between Bulgaria and Greece, and who once made a living from the border’s hardness by marketing his ability to sneak through safely. Or the old man in Thrace who grieved for his son and, tacitly, for the sons of other fathers whom he shot dead as part of his border army duties.

“If you're a border person, you cannot escape the border,” Kapka says. And this reveals another quality of borders: reiteration. Borders are formed through habit, but are also habit-forming and self-reinforcing. At one point during our conversation, Kapka reaches unexpectedly for a phrase from the child psychoanalyst Selma Fraiberg, “Trauma demands repetition.” This is why, she explains, “the border mentality has been reactivated…history repeats itself in the Balkans.” The Cold War is over, but today the borders are hardening once again.

In June last year, a 200-kilometre fence was completed between Bulgaria and Turkey. And it isn’t the only one. Hungary has erected a wall along its Serbian and Croatian borders. Slovenia has also cut off Croatia with a razor-wire fence. Macedonia has built a wall along its Greek border. Austria has reinforced its border with Italy, and France has built a wall in Calais, paid for by the UK Government.

The Syrian refugee crisis is the most immediate motivation. But human motives are rarely so straightforward. For all the harm that Bulgaria’s Communist-era border caused, you also get a sense, reading Kapka’s stories of the border people, that some still long for the border – for the black markets it created, for the authority it signified, for the divisions it instilled among peoples, for the sense of purpose it provided to the lives of the border guards. “ON THE NATIONAL BORDER, NATIONAL ORDER” declares a Soviet-era sign in Strandja. This nationalist mythology joins an accumulation of mythologies left by others who made their lives in the area: the Thracians, the Romans, the Seljuk and Ottoman Turks, and more.

“It’s the same thing recurring, like a revenant from the past,” she tells me. “You feel that when you’re in the forest, thinking, the new worlds are actually old worlds. You can actually see where the Iron Curtain no longer stands, you can see the scar across the land.”

Even when it is absent, the border is present.

*

“So vast, so fabulously varied a scatter of islands, nations, cultures, mythologies and myths, so dazzling a creature, Oceania deserves more than an attempt at mundane fact; only the imagination in free flight can hope – if not to contain her – to grasp some of her shape, plumage and pain.”

– Albert Wendt, Towards a New Oceania.

The Pacific is a creature not at all like the Balkans. Kapka tells me that when she emigrated with her family to Aotearoa New Zealand in 1992, “It was a shock to live on an island surrounded by ocean. It was a kind of drafty feeling, a feeling of extreme and unnatural – to me – openness. I had become so used to this idea of being surrounded by others. It had become quite cosy, almost comforting. It’s a European syndrome.”

She was “so astonished,” she says, that she wrote a book of poetry titled All Roads Lead to the Sea. “I had grown up with the Black Sea where there is something on the other side: another country. But here there is nothing on the other side, there is no other side...It rearranges your sense of what space means. It takes a while to adopt a Pacific perspective, but it’s incredibly liberating.”

Historically, however, others responded to this astonishment, to this sensibility of unfamiliarity, by imposing the familiar. This is one way to describe what colonialism did. In spite of the Pacific perspective, the Pacific is nevertheless divided by borders into nation-states, in line with the European model. In this sense, it isn’t so unlike the Balkans: a jigsaw puzzle of Exclusive Economic Zones that is draped over an ocean, rather than a continental landmass. Intriguingly, there is even a similar political history.

Kapka tells me that, in the Balkans, what came before nationalism was imperialism, the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the west, the Ottoman Empire in the east. It was the fall of these empires – a kind of decolonisation – that created the vacuum that nation-states filled. Prior to this fragmentation, Kapka tells me, the region was far more fluid and cosmopolitan, “the interface of Europe and the Middle East: that’s what the Balkans are, culturally speaking…It was all one territory, for thousands of years, until the beginning of nationalism. The actual physical fence amazingly only went up at the time of Berlin Wall in 1961. Until then, it was the rivers and the mountains that demarcated these borders.”

modernity has not only created borders, it has also substituted others

Of the Pacific, Lana Lopesi tells a story that resonates with this. She draws upon Albert Wendt and Epeli Hauʻofa to invoke an earlier imaginary of Oceania, “an oceanic expanse, a region that was based on the ocean, and within that multiple routes of trade that intertwined.” Here too there were empires, the Tongan, Samoan and Fijian Empires that governed pre-colonial patterns of trade. Then arrived European empires, a new layer of sovereign claims, along with new languages, religions, customs and systems of government. But then following World War 2 was an ushering in of a United Nations-mandated process of decolonisation that involved a crystallisation of national borders and state-centric institutions. So, a political settlement that emerged in continental Europe, designed in large part to contain war, was interposed upon an ocean.

It’s in this sense that Lana talks of “false divides,” the title of her forthcoming book. It interrogates, she says, “what it means for explorers to just come...and draw lines, or cut the ocean up. How crazy it is that that’s how a border is formed, that someone would just claim something, then that’s what’s embedded in you as a person today.”

She highlights the example of Samoa, an archipelago of three main islands that is administratively split into American Samoa and (formerly Western) Samoa, divided by its affiliations with the United States and Great Britain respectively. That division is further accentuated by diaspora communities, which peel away to either the United States or Aotearoa New Zealand and Australia, pollinating each territory with different solidarities and cultural resonances, with different senses of place. To even cross between these islands, only 30 kilometres from one another, requires a visa.

This cuts against the Pacific grain. Lana notes, “Oceania has always been a world where travel was a core component. People have never been locked to the islands. The ocean is just as important as the land.” And this spirit of mobility perseveres. It found a new expression in the 1970s through air travel and remittance economies, where people worked overseas in order to transfer their money to family back home. “Arguably,” Lana adds, “the internet has been able to reignite the naturally migratory nature of Pacific peoples.”

But modernity has not only created borders, it has also substituted others. Consider the New Zealand border. It’s easy to take this for granted, the border that you cross most conspicuously when you arrive at the airport to scan your passport, your visa or permit if you require one, and to submit to biometric recognition. This is overseen by Immigration New Zealand, on behalf of the government, and if you are lucky enough to have a New Zealand passport, you travel under the following authorisation: “The Governor-General in the Realm of New Zealand requests in the Name of Her Majesty The Queen all whom it may concern to allow the holder to pass without delay or hindrance.”

Such is the border around New Zealand, still redolent of the language that announced British sovereignty in the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. But Arama Rata, who co-authored with Tahu Kukutai an essay for Fair Borders?, tells me, “There have always been boundaries and borders in Aotearoa.” Prior to European arrival, there were tribal boundaries that marked out multiple Māori nations, headed by rangatira and ariki. Movement of people occurred across these boundaries, through trade or negotiated access to resources. There were procedures in place, such as pōwhiri, to regulate these crossings and to maintain peaceful relations. And at times, Arama says, they became “not just boundaries but borders. They were enforced and, in some ways, militarised, particularly in times of war. Aukati might be established to prevent the movement of people across boundaries. One really important example was...te pou o mangataawhiri, where a pou or symbolic stick was placed at the Mangataawhiri river, and Waikato-Tainui said that if that boundary was crossed, then that would be an act of invasion, which was what happened on 12 July 1863, beginning the Waikato Wars.”

So, prior to the national community of New Zealand there is a multinational Aotearoa, other nations and other authorities, grounded in mana whenua and projected through tino rangatiratanga.

And these borders persevere today. As Arama tells me, “Māori still refer to these boundaries as part of their way of identifying themselves and their relationship to particular places in Aotearoa through pepeha, through mihimihi, where you list important geographic features.” Other researchers are engaged in work that aligns government data to tribal territories, in order to enhance Indigenous data sovereignty at the levels of iwi and hapū. Arama argues that governance at the level of the rohe would also be preferable to Māori wards.

These divisions might imply divisiveness. Indeed there is a long-standing tradition of lobbying for “one nation, one people,” as if denying difference were the only sure way to prevent social discord.

But through whakapapa, Arama tells me, what divides us is itself a form of relationship-building. “Boundaries can be about recognising our differences, recognising what is distinctive about us, which then allows us to have a relationship. So, it would be very difficult for my people, of Taranaki, to have a relationship with, let's say, Ngāti Kahungunu without looking to our history, looking to our boundaries, looking to our shared lines of lineage. Acknowledging these things that make us distinctive then allows us to create relationships with others...Those differences are not insurmountable.”

It is this that gets lost when Māori nationhood is seen as identical to the exclusionary nationalism that once drove the “white New Zealand” policy, that conceives of a nation as homogeneous, in aspiration if not in reality. Unsurprisingly, those who see the world through this lens tend to interpret others as seeing the world the same way, as wanting to claim it all for themselves.

Yet this is, for Arama, precisely the problem. “In Aotearoa, Māori borders and boundaries were completely ignored. The mana whenua of Māori sovereign nations was ignored. This boundary around New Zealand was imposed by colonists, then used to settle the nation with what they regarded as desirable migrants – which were European people, white people. And along with the settlement of Aotearoa, they brought in ideologies, such as racism, which was used to create borders within New Zealand between people of different colours.”

*

“A utopia that has gone wrong in exactly the ways in which it should have gone right deserves a minute of silence and a lot of reflection.”

– Kapka Kassabova, Border.

There is a stately ambiguity about the title of Kapka’s book. It is about the Bulgarian border, but she tells me, also, that, “Border is a metaphor, a state of mind...it’s also about any border.”

I put it to her that Border could also be interpreted as a verb – “to border” – rather than a noun, in the sense that the border is a performance, an acting out of divisions between people.

She agrees, “I wanted to find out how people survived the border and therefore how they survived imposed and enforced identities. Because I really felt that this border, this particular border, has acted as an identity enforcer. Until a few years ago you were only Muslim, you didn't even speak Turkish, but now you are Turkish with this new border. You say it’s like a performance, well, it seems that nationality itself and identity politics are very much a kind of deadly game.”

According to the Bulgarian Interior Ministry, 415 people died on the border between 1961 and 1989, many shot and buried in unmarked graves. Now vigilantes patrol the same border in order to prevent people crossing from Turkey. Meanwhile, it is estimated by the Missing Migrants Project that 9659 people have died trying to cross the Mediterranean since 2014.

It is hard not to respond to this topic with anxiety about where the world is headed

It is hard not to respond to this topic with anxiety about where the world is headed. Aotearoa New Zealand had a brush with border madness in the lead-up to last year’s general election, but this pales in comparison to events internationally. I mentioned already the resurgence of walls across Europe. There is also Brexit, where a volatile anti-immigration politics is morphing into an impulsive and unpredictable secession from the European Union. There is Donald Trump’s lurid obsession with extending the southern border wall, escalating recently into a strategy of deterrence whereby children were separated from parents and detained. And then there is ‘neighbourly’ Australia which, since the Tampa crisis in 2001, has developed elaborate forms of mistreatment of asylum seekers, and more recently extended this hardline approach to non-citizens who commit, or are merely accused of, a crime. At the time of writing, there are concerns over a 17-year-old New Zealander detained in an adult prison in Melbourne for a minor crime, awaiting deportation to a country that isn’t his home.

Kapka tells me, “[There is] this idea that somehow we will be safer if we build this fence, and they don't come to us. But actually listening to all those Cold War stories along the border, we were not safer. In fact, living with a hard border makes life more dangerous for everyone. It hardens life, it hardens attitudes, it hardens fear, it hardens ignorance, it hardens suspicion within.”

Ultimately the damage emanates in all directions: it touches upon those inside the border as well as on the outside. A striking example is Theresa May’s 2012 pledge to create “a really hostile environment for illegal immigrants.” Inevitably, it metastasised, leading to the appalling treatment of the Windrush generation, Caribbean migrants who’d lived in England since the 1950s and 1960s, yet who were harassed by the Home Office, some forcibly evicted from their homes for deportation, others refused re-entry to the country that they’d lived in almost all their lives. So May’s hostile environment not only contributed to Brexit fever, but also incited the persecution of people who, far from being ‘illegal immigrants,’ were, among other things, British.

As Kapka tells us, it is difficult to escape borders. To some extent, these boundaries travel with us, in the way we place ourselves, or are placed by others. In writing her own book, Lana describes “a realisation that national borders and imperial borders are so deeply ingrained in you, as people, that they create these divisions that are physical but also mental, that are not aligned with how we once understood the world.”

Here lies the danger, the border as an alibi for national defence. It is the excuse that is needed to murder a stranger in a border forest, to imprison non-citizens, to separate children from parents. It occurs in more subtle ways as well, such as the withholding of visas to people with disabilities, in order to defend the social welfare system. Or the restriction of people of colour or ethnicity in order to defend some imaginary national unity.

Yet we should be wary of disavowing borders altogether. As Arama tells me, “Any people who have been invaded probably would be very hesitant about the idea of having no borders.” Laissez-faire utopias of free movement carry an uneasy echo of the liberties that colonisers presumed for themselves in regards to Indigenous peoples, encroaching upon existing territories as if by right, then erecting harder borders behind them.

borders aren't intrinsically evil, but where one group of people has control over those borders or boundaries, and uses that to assert their authority, oppress others, and exclude others, then we have a problem

Arama continues, “I think that borders aren't intrinsically evil, but where one group of people has control over those borders or boundaries, and uses that to assert their authority, oppress others, and exclude others, then we have a problem...In my view, there is an imperative that we as Māori have to decolonise the nation, but a really important part of colonisation is racism. If we allow racism to thrive, that makes the challenge of decolonising ourselves much harder. So an important aspect of our decolonising projects is anti-racism, and that's a point where we can work in solidarity with other peoples of colour in Aotearoa. And I think other peoples of colour must see that we can't eliminate racism without eliminating colonialism, so it is imperative for them to support Māori in their tino rangatiratanga movements.”

It is a feature of modern life that, as Étienne Balibar said, borders are everywhere. Perhaps we are all border people now, straddling various boundaries of place, status, citizenship, identity and standing. If there’s anything to this idea, then the extraordinary circumstances that Kapka describes might reveal something about our more ordinary circumstances.

“In the end,” Kapka tells me, “it seems that when you’re plundered, when you are stripped of the things that others enjoy – like infrastructure, a place in history, a livelihood, the people of the border don't have any of that really – but then they become what they love. That’s probably true of people who live in marginal communities. You become what you love: your flock of sheep, or the mountains. You identify with something that’s real, not something imaginary like your nationality.”

Fair Borders: A Panel Discussion

Wednesday 18 July 2018, 5:30pm – 6:30pm

AUT WG308 Te Iringa (Waveroom), Auckland