A Letter from Bombay, or Mumbai: On the Troubles of Renaming as a Decolonial Act

What's in a name? The history of a place, its present, and its future.

In the home studio of artists Shreyas Karle and Hemali Bhuta, tucked into a rocky cliff on the edge of the Borivali forest, my references to our locale disrupt the easy flow of our conversation. In describing my experience of returning to India from Aotearoa, I self-consciously stumble between referring to this city as Bombay, then Mumbai. When my family was preparing to emigrate in the 1990s, the city was called Bombay on the streets, even though it had been officially renamed Mumbai. This year, I have returned to relearn this city through its artists and galleries, and yet everywhere I go, I am alerted to people’s inconsistent use of the two place names – from art-world affiliates and conglomerate giants, from born-bred Maharashtrians and regional migrants, from expat communities and repatriate groups. In doing so, I discover that my feeling of being tongue-tied in this city is not unique, but is the result of a power struggle over space in the form of its naming and renaming, from the colonial period and before, and to the present day.

In the ongoing and multifaceted project for the restitution of justice, what is the role of naming and renaming?

In the South Asian subcontinent, it’s possible to track the footprints of European colonialism through toponymy – in the names of cities, in the divisions of polities, in borders and boundaries. Even in the naming of India, there is a trace of what the ancient Greeks called the people of the Indus River, Indoi. In Aotearoa too, European expansionists methodically overwrote Māori names of coastlines and landscapes. On October 6, 1769, a cabin boy aboard Captain James Cook’s Endeavour had sighted Te Kurī-a-Pāoa from its masthead, ‘the dog of Pāoa.’ But the headlands were renamed Young Nick’s Head and Nicholas was rewarded with a barrel of rum.[1] These new place names are our inheritance in a landscape that has been spatially segregated by Europeans. In the ongoing and multifaceted project for the restitution of justice, what is the role of naming and renaming? What is the relationship between toponymy and decolonisation?

Official history has it that Vasco Núñez de Balboa was the first man to see, from a summit in Panama, two oceans at once. Were the natives blind?

Who first gave names to corn and potatoes and tomatoes and chocolate and the mountains and rivers of America? Hernán Cortés? Francisco Pizarro? Were the natives mute?

The Pilgrims on the Mayflower heard Him: God said America was the promised land. Were the natives deaf?

Later on, the grandchildren of the Pilgrims seized the name and everything else. Now they are the Americans. And those of us who live in the other Americas, who are we?[2]

Just as those living in the other Americas had place names before European contact, so too did the tangata whenua of Aotearoa have names for their home. For the decolonial project, there is a genesis-based argument to be made for reinstating the pre-colonial place name. It is to remember the founding myths, to recall the beginning of things. But the impulse to recover origins is premised upon an unambiguous history of oppression. In the context of Mumbai, it seems difficult to claim belonging by way of indigeneity when human settlement in this region dates back thousands of years, with innumerable waves of migration and conquest. Is it possible to recover the city’s original name? And the name before it was a city?

Under the conditions of colonisation, what is remembered and what is forgotten becomes political

What was Mumbai called before it was known as Bombay? What did the Koli fisherfolk and Agri salt collectors call their home in the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE? What was it known as in the 2nd century BCE when the inhabitants of the cave-temples in Gharapuri, two kilometres offshore, cut sculptures of Shiva and erected Buddhist stupa, and when, at the same time, the Greek geographer Ptolemy named the seven islands Heptanesia? What did the Parsis call their new home when they arrived in the 8th and 10th centuries CE, fleeing the Muslim conquests of Persia? What did Dom Francisco de Almeida call the natural harbour when he arrived from Portugal in the 15th century? And what was its name before 1661 when the Portuguese Princess Catherine of Braganza was married to King Charles II, and the islands of Bom Bahia were given to England as part of her dowry? And what was it called before the Mumba Devi temple was built in 1675, and from where we derive the city’s name today?

Following philosopher Saul Kripke’s causal theory of reference, proper names refer to their objects via a causal chain going back to the object’s ‘baptism.’ Once upon a time, a white sahib must have pointed to the boulevard in Malabar Hill to name it Nepean Sea Road, which must have triggered others to call it the same. Still today, this costly neighbourhood is called Nepean Sea Road, even though it has been officially changed to Lady Laxmibai Jagmohandas Marg. Even if this port city was created by Portuguese and British effort, it does not prevent a re-baptism to displace or augment old, imperial names by the same causal chains. These instructions are upheld by each use, in each instance. “We, collectively, have the authority to pass on these names, or to replace them. Whatever we do – continue the chain or disrupt it – we are making a choice about whether to uphold the honour intended by those baptisms.”

Under the conditions of colonisation, what is remembered and what is forgotten becomes political. Memory was a tool with which the colonial instrument was sharpened. And in the name of education, there was introduced an epidemic of forgetfulness.

The purpose of renaming, or reinstating the pre-colonial name, is to remember, recall and recollect. “It is important that descendants of the colonised do not have to live in societies that honour those who oppressed their ancestors. It is about eradicating racism, a direct legacy of colonialism.”

Language and epistemology are inseparably and intrinsically linked; what we call a thing is also what we can come to know about it

Naming is also a speech-act, an example of what the philosopher J L Austin has called a ‘performative utterance.’ It is an event whereby saying something makes it so: “I do,” or “I name these headlands after Young Nicholas.” But not all naming is felicitous, and not everyone is faithful to unsolicited attempts. In How to Do Things with Words, Austin writes:

Suppose, for example, I see a vessel on the stocks, walk up and smash the bottle hung at the stern, proclaim: ‘I name this ship the Mr. Stalin’ and for good measure kick away the chocks: but the trouble is, I was not the person chosen to name it… We can all agree (1) that the ship was not thereby named; (2) that it is an infernal shame.[3]

Austin shows that authority to name does not exactly belong to an individual; it requires a social contract, an implicit or explicit agreement with those who choose the name. It was the Royal Navy who gave Captain James Cook the authority to name the headlands of Aotearoa. The naming of a place is an expression of power, at once administrative and political. It is to exercise influence in a public way, by way of signs and symbols. Language and epistemology are inseparably and intrinsically linked; what we call a thing is also what we can come to know about it. And so the study of place names is the study of identity and ideology, taking into account place and purpose at once. While the struggle is about profound structural change in order to liberate ourselves from our colonial entanglements – which we may, for the moment, be unable to transcend – then at least through the renaming process it is possible to face the history of colonisation with as much openness and self-reflection as possible.

The renaming process forms one part of a wider socio-political, cultural and economic struggle in the decolonial efforts of museums and galleries. Other efforts have included the return of stolen treasures, the renaming of artworks with racist titles, and consultation with Indigenous communities for determining the future of museums and galleries.

When the influence of the British Raj was declining, the Imperial Institute in London was compelled to rethink its programme, supported as it was by the profits of the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886. Part of its core business until this point had been to research and share information about raw materials extracted from British colonies, but when regions in Asia, Africa and the Middle East began to achieve independence, it was renamed the Commonwealth Institute. Now, even the Commonwealth Institute does not exist; it was liquidated in 2002, and its London premises were given over to the Design Museum, which is an altogether different organisation that bears little connection to the colonial institutes of the past.

More recently in London, the British Museum has renamed its gallery that explores the impact of farming in the Middle East and its introduction to Europe in the honour of His Highness the late Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, the founder of the United Arab Emirates. In the United States, the San Diego Museum of Man is requesting community feedback on five possible new names. And in recent years at home in Tāmaki Makaurau, a number of arts organisations have undergone different processes of naming and renaming, including Te Tuhi, Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery and Te Oro.

Place names are sites of memory, and in their letters are inscribed the histories of their people. “While memory is seemingly about the past, it is shaped to serve ideological interests in the present and to perpetuate certain cultural beliefs into the future.”[4] Giving a place a name can be in order to translate memory onto the site, but it can also be just as effective at hiding the past as revealing it. What was obscured by the erstwhile Victoria and Albert Museum in Bombay, until it was renamed in 1975, was the work of those who enabled its establishment in the Bombay Presidency of the British Raj in the name of Her Majesty The Queen and His Royal Highness The Prince Consort. In 1851, at the same time that Sir Henry Cole and Prince Albert were preparing The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations in London’s Crystal Palace, the idea of setting up a museum in Bombay – the Urbs Prima in Indis – was mooted by a group of “public-spirited citizens.”

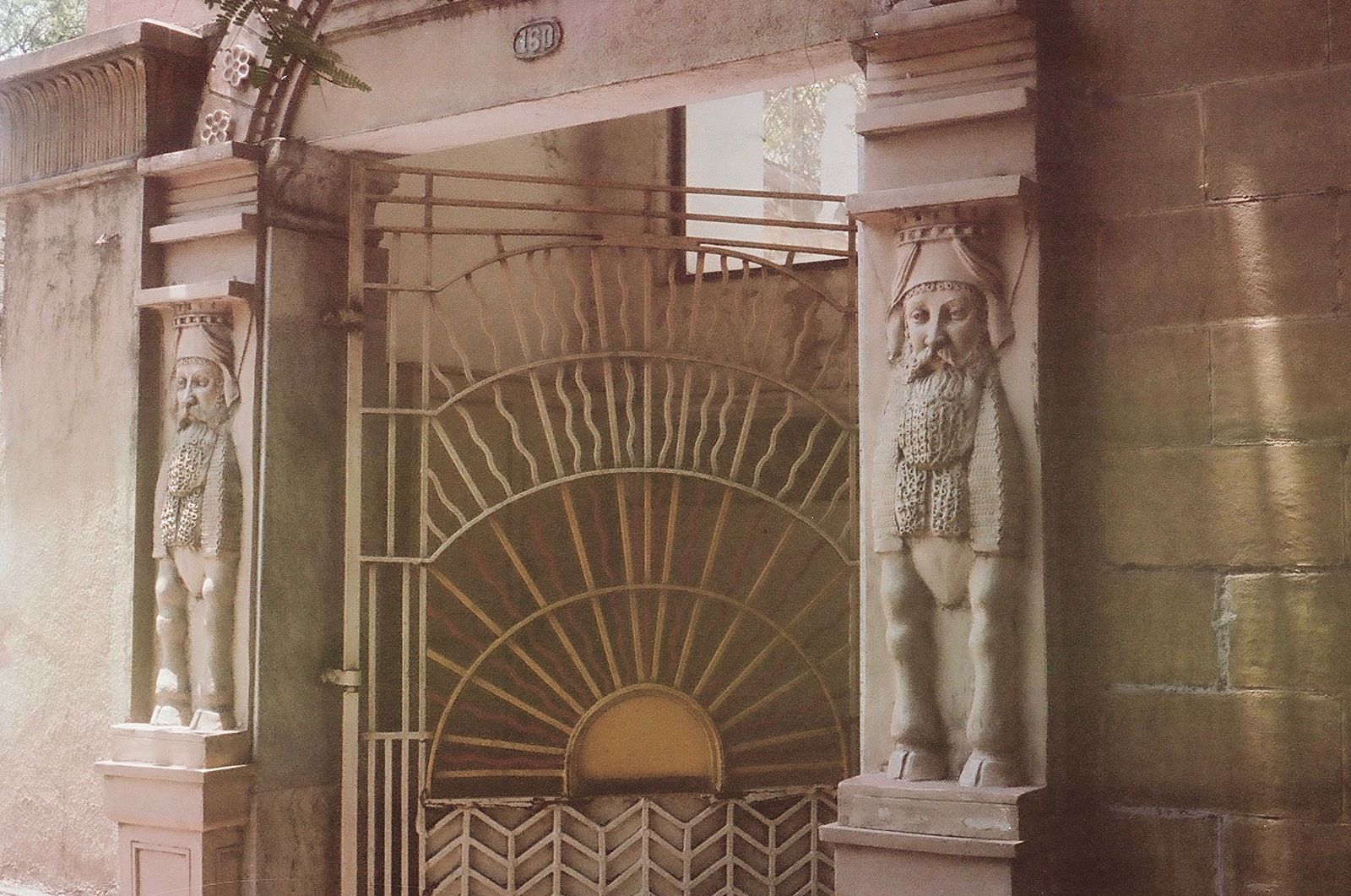

When a public meeting was called in the Town Hall, which today houses the Asiatic Society of Mumbai, an Indian physician and scholar of Sanskrit named Dr Bhau Daji Lad was selected, alongside Dr George Birdwood, as secretary, and “charged with raising funds to establish the building and enlarge the collection with the best specimens of ‘Indian manufactures.’” The sum of 1.16 lakh rupees was raised from local public subscription with the help of Dr Bhau Daji Lad, who at the time served as the first native Sheriff of the burgeoning port city. (Most online inflation calculators put 1.16 lakh rupees from mid-19th-century India at more than $20M NZD in today’s currency.) The plan to build a Hall of Wonder in a grand Neo-Renaissance style was conceptualised by Dr George Birdwood, and in 1872, the Victoria and Albert Museum was opened to the public: a building richly coloured with green and gold accents, with Corinthian and Doric columns, and with Thomas Minton and Sons flooring imported from Staffordshire. A little more than a hundred years later, in 1975, the museum was renamed to honour the late Indian physician and Sanskrit scholar.

Whereas the colonial power relations of the 19th-century British Raj are revealed through the renaming of the Victoria and Albert Museum after Dr Bhau Daji Lad, the reason for renaming the Prince of Wales Museum of Western India to Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya remains a little more obscure. I must agree with Ayyappan Pillai’s comment on Quora that “the architecture and the nomenclature just don’t add up!” There is something incongruous about naming Indo-Saracenic architecture after 17th-century Chhatrapati of the Maratha Empire. The link between the late-19th-century British-Indian architecture style and the Maratha is tenuous, if not altogether missing. And the irony is complete when the people of Mumbai – taxi drivers and shop owners alike – prefer to clip the grandeur of this name to its Roman initials, CSMVS. To be sure, this is not to a call for historical accuracy, but rather to question the values expressed by applying his name to the museum built to commemorate the arrival of Prince Albert in India. And to be twice sure, neither is it to argue for the retention of a British title for an Indian museum. Instead, what the choice makes clear is that renaming is just as much about the present as it is about the past. As symbols to which people ascribe meaning, place names are effective in revealing the political climate of the day, just as much as remembering forgotten things. A place name shows its people’s attachments, and what is illustrated by the renaming of CSMVS is a reverence for the glory days of the Maratha past. The renaming of the civic museum is just one example in a number of other instances commemorating Shivaji, including the name change of Victoria Terminus railway station to Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus, and Sahar International Airport to Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj International Airport.

In the sprawling concrete jungle of Mumbai, the groves that once flourished here can be recalled in the names of the city’s neighbourhoods. The place names evoke a greener past which is lost in the city smog. On the eastern slopes of Malabar Hill, gum trees named babul gave Babulnath its name, and there is an old Shiva temple for the ‘Lord of the Babul’ on a small hillock nearby. Cumballa Hill refers to the kambal, a type of deciduous ash tree used as anti-inflammatory medicine in Ayurveda. Parel is from the flowering shrubs of ‘the angel’s trumpet,’ or ‘moonflower,’ and Chinchpokli is from the Marathi name for a valley of tamarind trees. There were tad palms in Tardeo, and vad trees in Worli. The fig tree creek of Umarkhadi, and the umbrella trees of Bhendi Bazaar. In an essay on the relationship between place names and decolonisation, recalling flora and fauna may feel benign, not because the naming system follows a pleasant logic, but because it is difficult to read these place names within the wider socio-political context.

The megalopolis of Mumbai is built on what was once an archipelago of seven islands, which was known to the Greek geographer Ptolemy, in 150 CE, as Heptanesia. Pleistocene sediments suggest that the islands were inhabited since the South Asian Stone Age, but nothing certain can be known about these ancient peoples. The earliest known accounts are from the 4th century BCE when Koli fisherfolk and Agri salt collectors called these islands their home. Then, in the 3rd century BCE, the islands were incorporated into the Buddhist Maurya Empire.

The city was called Bom Bahia or Bombaim by the Portuguese, ‘the beautiful bays’

Between the 2nd century BCE and 9th century CE, the islands were ruled by successive dynasties, until the reign of the Shilaharas from 810 to 1260. In the late 13th century, King Bhimdev founded his kingdom in today’s Mahim district. The Delhi Sultanate annexed the islands in 1347 and controlled them until 1407 when they were then governed by the independent Gujarat Sultanate. During the 16th century, the Mughal Empire became the dominant power in the South Asian subcontinent. Sultan Bahadur Shah of Gujarat, weary of the influence of the Mughal emperor Humayun’s power, signed a treaty with the Portuguese Empire in 1534 which included an offering of the seven islands of Bombay as well as the nearby strategic town of Bassein and its dependencies.

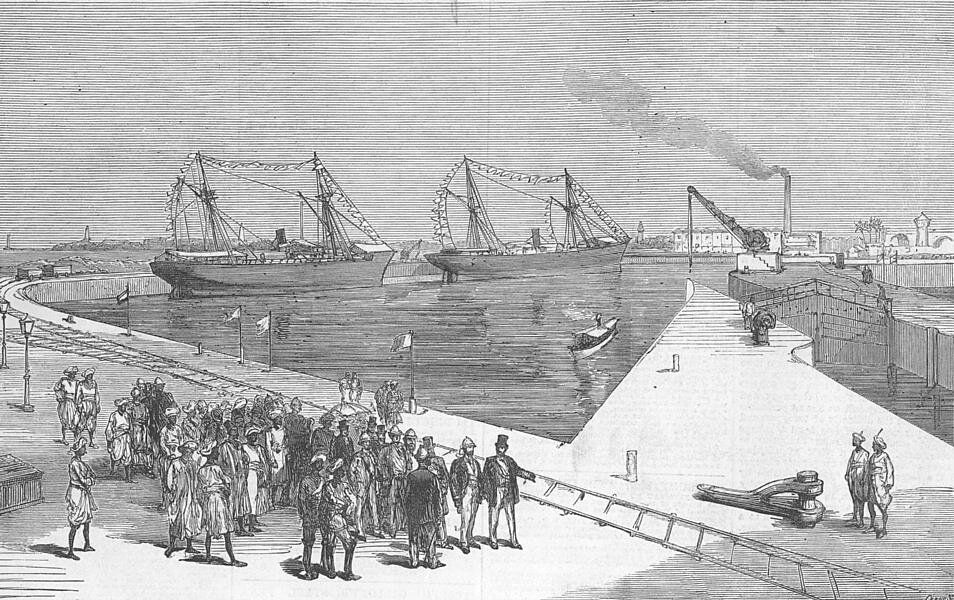

The city was called Bom Bahia or Bombaim by the Portuguese, ‘the beautiful bays.’ During the 17th century, the British vied for hegemony over the islands because of their strategic natural harbour and isolation that protected them from land attacks. In 1661, when the Portuguese Princess Catherine of Braganza was married to King Charles II, the islands of Bom Bahia were given to Britain as part of her dowry. The Portuguese presence ended in Bombay in 1739 when the Maratha Empire captured Salsette and Bassein. But with the defeat of the last Maratha Peshwa in 1817 by the British, almost the entire Deccan Plateau came under British suzerainty and was incorporated into the Bombay Presidency of the British Raj. From 1782 to 1845, the city was reshaped by large-scale civil engineering projects aimed at merging all the seven islands of Bombay into a single amalgamated peninsula; and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 transformed Bombay into one of the largest ports on the Arabian Sea.

When the British Raj ended in 1947, the decolonial process began not only by discharging the white sahib from his administrative post, but contending with the different claimants of each state, city and neighbourhood. The Samyukta Maharashtra movement quashed Bombay’s possible status of independence, either as an autonomous city-state or as the capital of a bilingual state incorporating Maharashtra and Gujarat. In 1960, following protests in which 105 civilians died in clashes with the police, Bombay State was reorganised along linguistic lines. Gujarati-speaking areas of Bombay State were partitioned into the State of Gujarat, and the State of Maharashtra was formed with Bombay as its capital.

It became a self-mythologising city, the setting of innumerable fables in books and movies...

Despite the conflicts over the city’s governance post-Independence, the cosmopolis of Bombay blossomed as a civic model for India in the mid-20th century, becoming the financial and entertainment capital of the country. It became a self-mythologising city, the setting of innumerable fables in books and movies: Salman Rushdie’s The Moor’s Last Sigh and Midnight’s Children, Rohinton Mistry’s Such a Long Journey and Family Matters, Suketu Mehta’s Maximum City, and more than 300 titles in Hindi cinema.

The post-Independence decolonial efforts also included symbolic amendments like respelling or overwriting colonial place names. Madras in the State of Tamil Nadu was renamed Chennai, Calcutta in West Bengal was respelled Kolkota, Bangalore in Karnataka became Bengaluru. Bombay was officially renamed by legislation in 1995, and under the Shiv Sena Government in Maharashtra, the city became Mumbai. The city’s name is derived from Mumbadevi, the name of the patron goddess of the Koli fisherfolk who migrated to the islands from present-day Gujarat. A temple was built for her in 1675, in what is now the Bhuleshwar district of the city. But there are older names that refer to the archipelago, Kakamuchee and Galajunkja, which are still sometimes used. The renaming of Mumbai under the influence of the Shiv Sena political party did not stop at the level of the city; it extended to landmarks, roads and intersections. “Over fifty road-renaming proposals are put before the municipal corporation each month. Between April 1996 and August 1997, the civic administration approved 123 such proposals. The roads committee of the municipal corporation spends 90 per cent of its time renaming.”[5]

The shift from Bombay to Mumbai was concomitant with the shift in the representational space of the city. For many, the renaming of Bombay to Mumbai signalled the decline and dissolution of Bombay’s iconic status as a global city of the geopolitical South. The economic decline and the loss in soft power that the city suffered in the late 20th century coincided with the rise and radicalised populism of the right-wing Hindu fundamentalist party Shiv Sena:

Sometime in the 1970s [...] a malignant city began to emerge from beneath the surface of the cosmopolitan ethos of the prior period. The change was not sudden, and it was not equally visible in all spheres. But it was unmistakable. [...] The groundwork was laid for the birth of the most markedly xenophobic regional party in India – the Shiv Sena – which formed in 1966 as a pro-native, Marathi-centered, movement for ethnic control of Bombay.[6]

In 1992, Hindu vandals destroyed the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh, sparking a wave of Hindu-Muslim riots that spread to Bombay. The civilian conflicts of Bombay in late 1992 and early 1993 saw thousands of Muslims massacred and a quarter-million of them flee the city.

Since this period, mostly through the active and coercive tactics of the Shiva Sena and its cadres, Bombay’s Marathi speakers have been urged to see the city as theirs [...] In keeping with more than two decades of the Shiva Sena’s peculiar mix of regional chauvinism and nationalist hysterics, Bombay’s Hindus managed to violently rewrite urban space as sacred, national, and Hindu space.[7]

The difficulty in Mumbai is that decolonisation is confused as a de-Islamisation. The populist rhetoric of the ruling party sees European colonialists as only the most recent in a succession that includes Islamic rulers of old India (discounting the fact that many of the Muslim citizens of Mumbai wouldn’t themselves be descendants of Middle-Eastern peoples, but share a claim of indigeneity to India by way of ancestry). “The idea is to go back not just to a past but to an idealized past, in all cases a Hindu past.”[8] The recovery of origins is a dangerous idea in this port city when the ruling party’s ideology promotes regional chauvinism, in which Bombay belongs to Maharashtra, the state in which it is located, and thus to Maharashtrians, and Hindutva, or Hindu supremacism, in which Bombay is part of the sacred geography of a Hindu nation.[9]

The decolonised or indigenised Hindu regime too readily discounts the pluralistic reality of the city, and the effect on the lived experience of minorities is violent

Not only Muslims are considered outsiders, but also Buddhists, Jains, Christians, Sikhs and Parsis, and even Hindu speakers of Gujarati; which is ironic since the first known peoples of Mumbai, the Koli fisherfolk, came from ancient Gujarat, and their patron goddess, Mumbadevi, gives the city its name. The decolonised or indigenised Hindu regime too readily discounts the pluralistic reality of the city, and the effect on the lived experience of minorities is violent. “[E]very few years a new enemy is found among the city’s minorities: Tamil clerks, Hindi-speaking cabdrivers, Sikh businessman, Malayali coconut vendors – each has provided the ‘allogeneic’ flavour of the month (or year).”[10]

Luckily, I pass in Mumbai with a Marathi last name, even if my birthplace was Hyderabad and I call Tāmaki Makaurau home

Visiting Bombay as a child was “an arrival into cosmopolitanism and attendant anxieties about national identity and belonging”[11] but landing in Mumbai is altogether different. The voice of the ruling party now forcibly asserts that it is to a pan-Hindu – no, pan-Marathi – place that I have arrived. That is where I supposedly stand, and my belonging in this city is moderated in relation to this assertion. Luckily, I pass in Mumbai with a Marathi last name, even if my birthplace was Hyderabad and I call Tāmaki Makaurau home.

The history of this city is layered. Its fragments are dismembered and misremembered, and there is an unevenness to people’s recall. There are inconsistencies, and recollecting is a fallible process augmented by prejudices and preferences. In a city that is being increasingly defined by exclusionary identity politics, the process of decolonisation must be cautious, remembering that not everyone shares the same meaning, impulse, and interpretation of what a decolonial action is. We ought to refrain from superficial forms of ticket-clipping on the grounds of colour, and instead become attentive to the processes of recovery. “If we simply replace an elite, imperialist white man with an equally elite black man then we are failing to really decolonise anything, unless it dismantles and challenges systems of hierarchy such as the patriarchy, class-based hierarchies, and sexuality.” It is a matter not of rearranging but of removing the physical, emotional, and spiritual damage of colonised people.

Here, I cannot take renaming at face value, as an inherent and unquestionable form of decolonisation

In Aotearoa, decolonisation is seen, for the most part, as a fundamental process for the restitution of justice – not only for Indigenous people to reclaim resources, but also to recover minds and bodies from European ways of perceiving, relating and existing. My alertness to people’s uses of place names in Mumbai is partly because when I return home, the gallery for which I work, ST PAUL St Gallery at Auckland University of Technology, will soon also be renamed. Even while I have been away, there have been changes to place names in the Aotearoa, like officially reinstating the Māori name Tūranganui-a-Kiwa alongside Poverty Bay, and reintroducing the letter h in Whanganui. But in Mumbai, my sense of the decolonial project is made topsy-turvy. Here, I cannot take renaming at face value, as an inherent and unquestionable form of decolonisation.

The challenge in Mumbai, as it is everywhere in the decolonising worlds, is how to ensure equitable representation across multiple communities bordered and bound by caste, class and creed. Socio-economic, political and cultural citizenship depend on intersecting economies of representation. My friends say Bombay did a better job of accommodating everyone than Mumbai. Their counter-argument for retaining the name Bombay, at least on their tongues and in their email signatures, is to enact a form of resistance against the narrowing effects of the ruling party. But calling the city Mumbai marks the transmutation in ideology and outlook, and underscores the altogether different set of power relations of the present day. If the political task is to recognise and make sense of how the Hindu Right have achieved “a necessarily incomplete hegemony over Mumbai’s image and reality,”[12] then I can begin to recognise this lived reality only by calling it Mumbai. Bombay is lost, and constructing alternative narratives to the Hindu Right cannot be in nostalgic tones. It is in the crevices of these concerns – in the decolonising of our public spaces, our cities and their museums – that naming and renaming has its proper place.

[1] K. J. Belshaw (Ngāti Awa), “Decolonising the Land – Naming and Reclaiming Places,” Naming Places, (December 2005): 8. [Macrons added]

[2] Eduardo Galeano, Mirrors: Stories of almost everyone, trans. Mark Fried (New York: Nation Books, 2009), 122.

[3] J. L. Austin, How to Do Things with Words, ed. J. O. Urmson and Marina Sbisa (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1962), 23.

[4] Melissa Wangui Wanjiru and Kosuke Matsubara, “Street toponymy and the decolonisation of the urban landscape in post-colonial Nairobi,” Journal of Cultural Geography, 34, no. 1 (2017): 3.

[5] Suketu Mehta, Maximum City: Bombay lost & found (Gurgaon: Penguin, 2006), 139.

[6] Arjun Appadurai, “Spectral Housing and Urban Cleansing: Notes on Millennial Mumbai,” in Cosmopolitanism, ed. Carol A. Breckenridge, Sheldon Pollock, Homi K. Bhabha, and Dipesh Chakrabarty (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002), 629.

[7] Ibid. 629–630.

[8] Suketu Mehta, op cit. 140.

[9] Rashi Varma, “Provincializing the Global City: From Bombay to Mumbai,” Social Text, 81, vol. 22, no. 4 (Winter 2004): 66.

[10] Appadurai, op cit. 630.

[11] Varma, op cit. 2.

[12] Varma, op cit. 83.

Header image: Emma Gleason (Passage Journal), 2018.