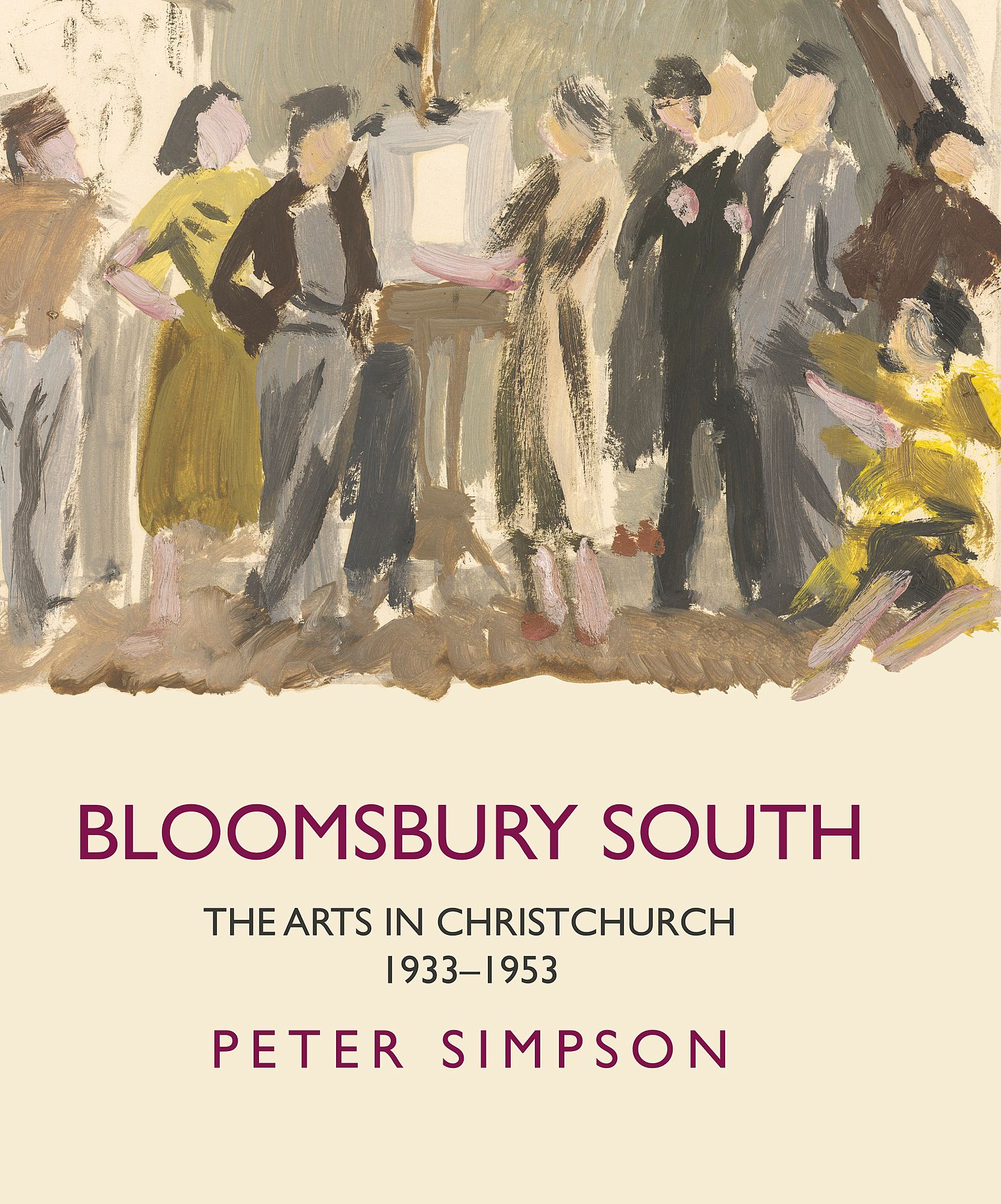

A Golden Autumn: Peter Simpson's 'Bloomsbury South'

Simon Palenski on an ambitious new book that examines the art scene in Christchurch in the 1930s through '50s.

Simon Palenski on an ambitious new book that examines the art scene in Christchurch in the 1930s through ’50s.

Facing the first page of Bloomsbury South: The Arts in Christchurch 1933–1953 is a photograph taken in Christchurch in the early 1930s. It looks north up Colombo Street, past the Hereford Street intersection, towards Cathedral Square. Throngs of people on bikes and foot, a few old-looking cars, and a tram make their way along the street. Narrow, terraced buildings with a motley assembly of signs line both sides. The spire of the Anglican Cathedral reaches up in the background.

Peter Simpson notes that from where the photographer stands, most of the locations that feature in the book are within strolling distance: Canterbury University College, the Caxton Press, Durham Street Art Gallery, the offices of The Press, the flats where Rita Angus and Leo Bensemann lived, as well as the bars, theatres, restaurants, and other places people met. His conclusion is that this proximity allowed a closely intertwined arts community to form in Christchurch, akin to London’s Bloomsbury Group of Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf, Leonard Woolf, Duncan Grant, and others.

Simpson goes on, “The city I write about in Bloomsbury South is even more remote now than it would have seemed five years ago – ‘all changed, changed utterly’ in Yeats’ phrase.” Today, if you were to stand in the same spot on Colombo Street, you would have to agree. Amid Christchurch’s noisy, slow rebuild, the book is a kind of window into an apparently more glamorous time.

So, the Christchurch of Bloomsbury South is gone. And, Simpson argues, the city has never reached the same national, artistic heights since the golden age of 1933 to 1953. That is, when an ‘A team’ of Angus, Bensemann, Ursula Bethell, Denis Glover, Allen Curnow, Charles Brasch, Colin McCahon, Toss Woollaston, Ngaio Marsh, Douglas Lilburn, Doris Lusk, James K. Baxter, and a few others all lived in Christchurch, making art, and trying to define what New Zealand art should be.

The time was, in Simpson’s words, “a brief flowering”. As with Bloomsbury London, the artists of ‘Bloomsbury South’ banded together against the establishment and mainstream values. Nearly all of them were homosexual or bisexual, left-leaning, and pacifists or conscientious objectors. Their sexualities and beliefs would pit them against a conservative public, particularly in Christchurch.

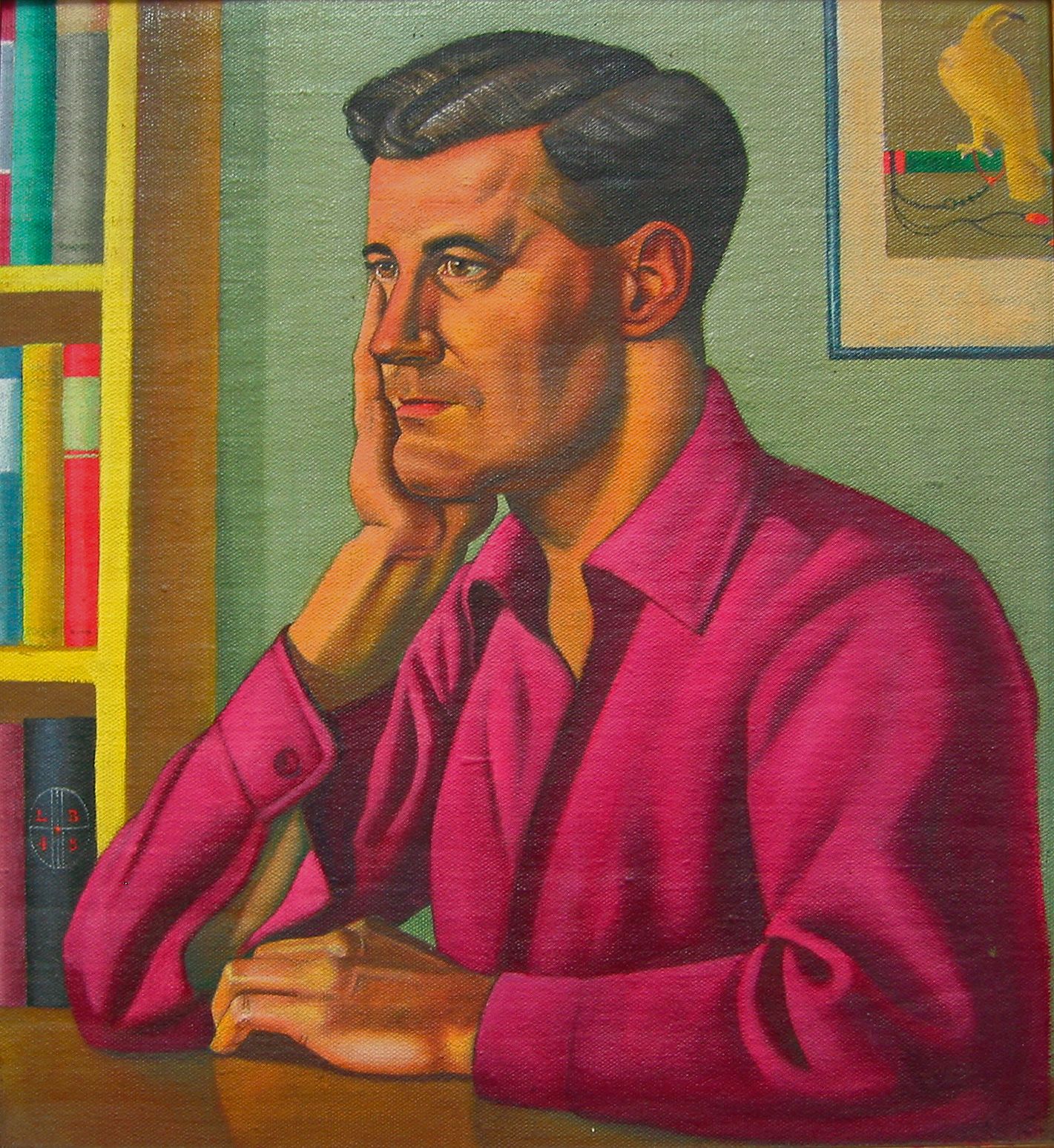

Bloomsbury South feels like the summit of much of Simpson’s previous work. He has published books and curated exhibitions concerning McCahon, John Caselberg and McCahon, Brasch and McCahon, Baxter and McCahon, Bensemann, Angus and Bensemann, and Curnow. He has taught New Zealand literature and art at universities. These people and their times have been an interest and focus for Simpson for most of his career.

In the preface, Simpson recalls how, as a student at Canterbury University College in the 1960s, he was made aware of this age that “definitely if mysteriously faded” a decade before. A few remnants were still there. Lawrence Baigent was one of his teachers. He met Lusk, Bensemann, and Brasch at university parties, bought books over the counter from Bensemann at Caxton, and saw new paintings by McCahon and Woollaston. Years later, when he returned to Christchurch to teach at the new University of Canterbury campus, now deep in the suburbs of Ilam, these vestiges had in turn vanished.

Each chapter of Bloomsbury South focuses on a part of the bygone age. The book starts with the poet Bethell and her circle of young male acolytes, then moves to the early years of the Caxton Press and the artist cooperative The Group. Lilburn and Marsh get a chapter each. The later years of Caxton and The Group are examined, then Brasch and Landfall. McCahon and Baxter round out the final years. It all comes to an end with the last chapter, ‘Consolidation and Dispersal’.

Simpson avoids a linear approach, moving back and forth between people, places, and events. Everyone appears in everyone else’s chapter. The overlapping, collaborative nature of the time and the intricate, personal nature of the relationships are brought to the fore. Among the broad strokes of modernism, regionalism, and nationalism, it is staggering to think of the amount of material (publication lists, exhibition catalogues, unpublished letters and notebooks) Simpson has had to find and pore over in order to fill in the minute details.

The overlapping almost leads Simpson’s narrative to go full circle. A line from Brasch’s poem ‘The Estate’ opens the story: “I think of one who … from her high garden / Studied a landscape for years …” ‘Her’ being Bethell – alone in 1934, following the death of her companion Effie Pollen (‘companion’ is Simpson’s term; Sarah Jane Barnett sees them as lovers), and writing endless letters to friends scattered overseas. The book ends in 1953, when the Little Theatre (home to Marsh’s theatre company) burns to the ground. Marsh, now living in London, briefly returns to Christchurch and stages one last production (Julius Caesar) on a temporary stage in the Great Hall next door. Like Bethell 20 years before, she is alone.

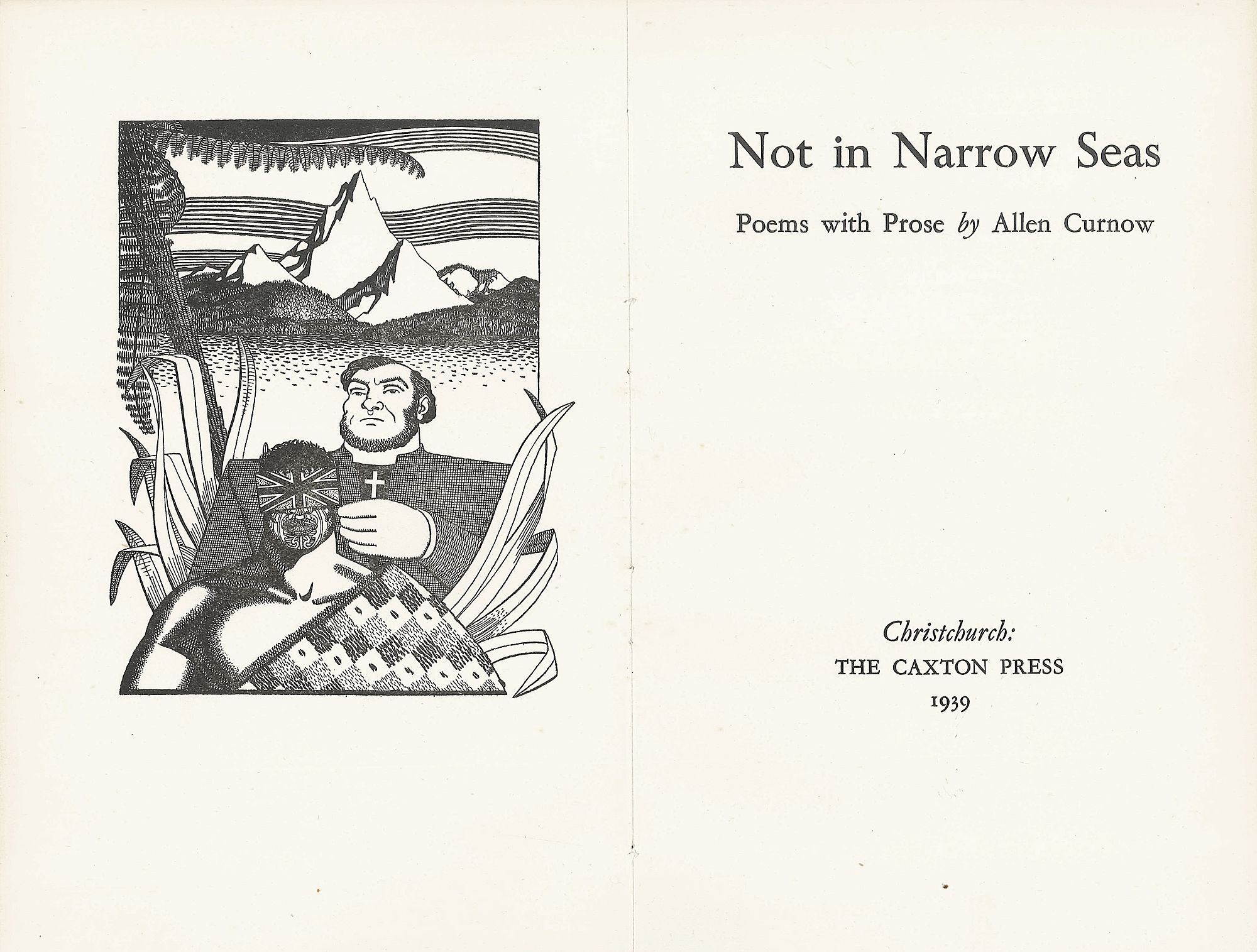

It mystifies Simpson as to why such a creative group of people suddenly converged on Christchurch in the mid 1930s. At the start, it seems like pure serendipity. Bethell needs help gardening and a friend from her church recommends a penniless, young art student she knows. And so Woollaston turns up, and they strike up a friendship. At the same time, Caxton emerges, and goes about positioning itself as a publisher of the new New Zealand literature. This includes the poetry of Bethell, who is soon an established source of advice and criticism for a swathe of young men, including Curnow, Glover, Brasch, and Monte Holcroft, all of whom are published by Caxton.

Caxton becomes a centre of the “radiant network” of Bloomsbury South. Aside from books, they also design and print the annual Group catalogues, Marsh’s theatre programs, Lilburn’s music scores, and the journal Landfall, which is set up by Brasch in 1946. The story of Caxton shows the casual, collaborative nature of Bloomsbury South, and Simpson emphasises that this, in part, makes the group unique in New Zealand and links it to Bloomsbury London. There are other examples. Lilburn composes music for Curnow’s poems and Marsh’s plays. McCahon and Baxter swap paintings and poems. Curnow and Baxter review each other’s books.

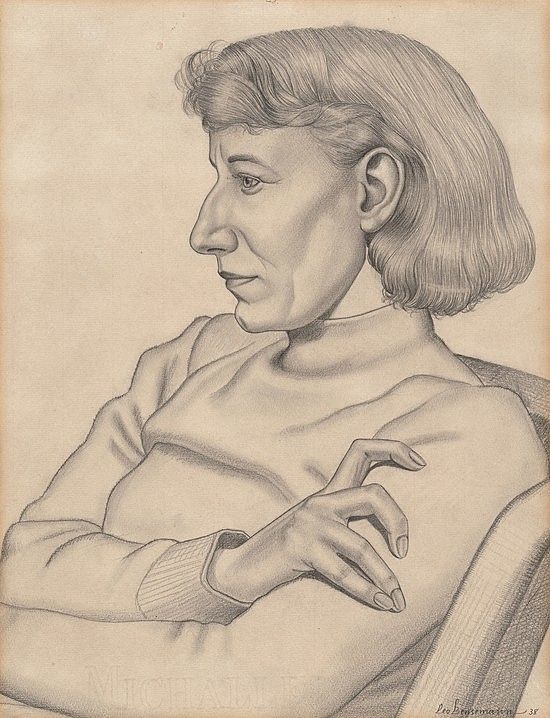

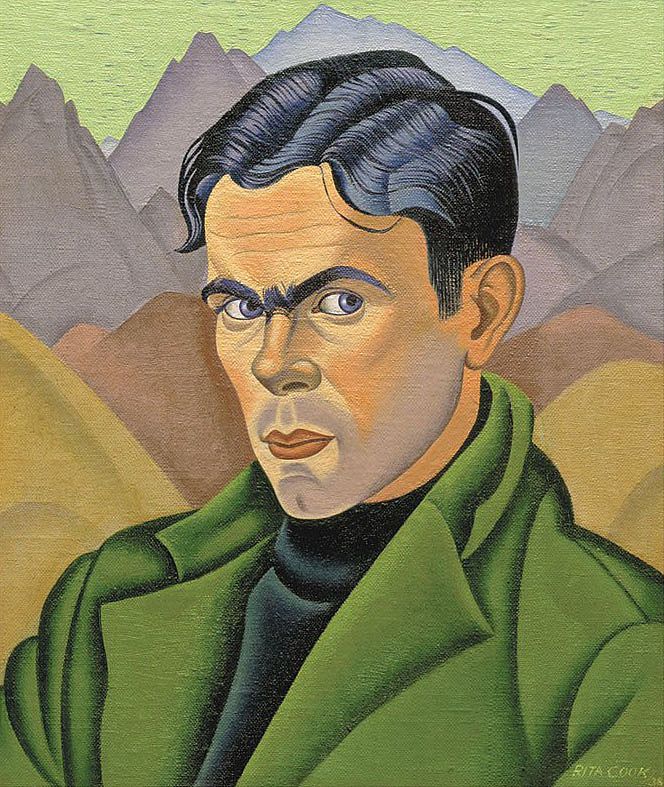

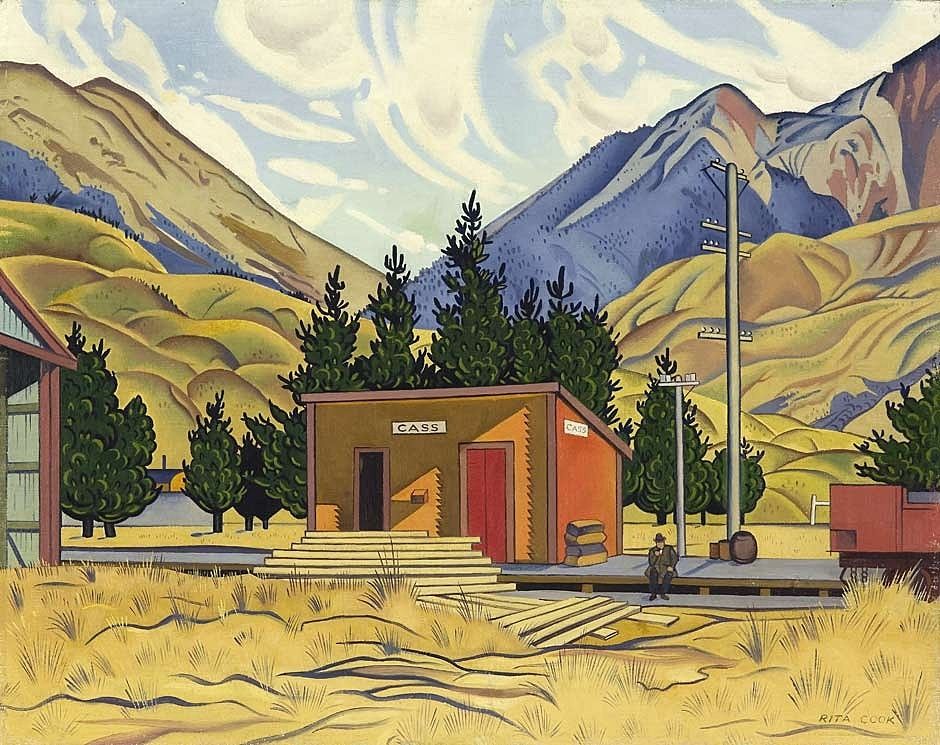

From here, the network extends further. In 1936, Angus moves into a shared house/studio on Cambridge Terrace. And the paintings she soon finishes there (like Self-Portrait and Cass) announce her as a bold, new talent. Bensemann, recently hired by Caxton, moves in with his friend Baigent. With Angus, they form a relationship of “affectionate intimacy”, and their flat becomes the unofficial headquarters of The Group, and a regular drop-in place for artists, musicians, and writers.

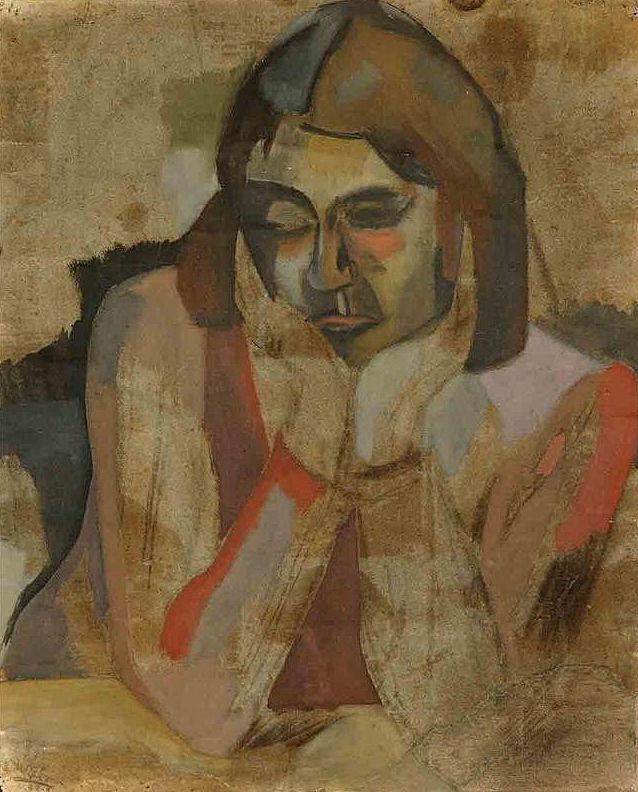

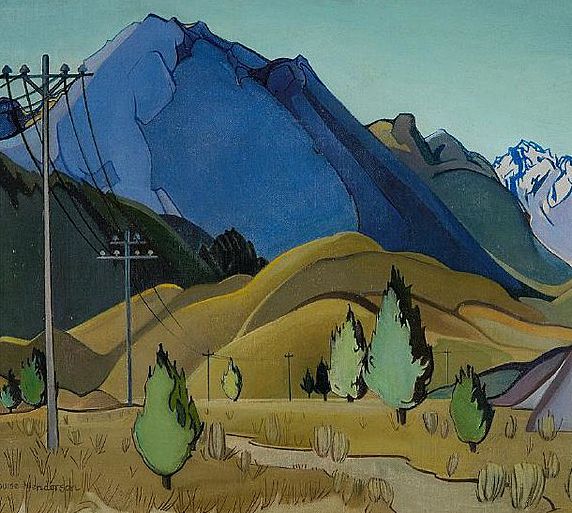

With The Group, Angus, Louise Henderson, Olivia Spencer Bower, and other, mainly women, artists find a way to challenge Christchurch’s art establishment. Bethell, Curnow, Brasch, and Glover do the same with writing and publishing, Lilburn with music, and Marsh with theatre. The activity attracts similarly motivated artists like McCahon, Baxter, and Bill Pearson, who move to Christchurch after the war.

Within the expanding story, the best bits are the small details that Simpson highlights: McCahon unrolling The Virgin and the Child Compared in a hotel pub to show Baxter and Pearson, Angus’ Clifton cottage designed by Paul Pascoe, a photograph of Lusk’s living room wall crammed with paintings by her friends.

Aside from serendipity and the inexplicable, spaces for new art and thinking seem to play a key role in Christchurch becoming an artistic centre. “Individuals come and go, but institutions tend to be more stable and enduring, or even to have a certain in-built inertia”, Simpson argues in the conclusion. A space can be a social flat, an independent publisher, or a friend’s backyard shed offered as a studio (it was in Lusk’s shed that McCahon painted Takaka: Day and Night). These spaces are held up and examined by Simpson in detail.

However, it is the people that truly make up Bloomsbury South, and when they begin to leave the scene shrinks and dies (and, as Simpson seems to infer, never returns). Nearly everyone moves to Wellington, Auckland, or overseas by the end of the book. Caxton and The Group go on, though Simpson notes that they lose much of their venom.

Christchurch’s conservatism appears to be a main cause of people leaving. Frederick Page and Lilburn, both turned away by the College’s music department, find work instead at Victoria University. McCahon (outside of some prescient friends) only meets criticism and discouragement with his painting in Christchurch; he moves to Titirangi in 1953, and, three years later, becomes deputy director at Auckland City Art Gallery. Angus and Woollaston receive their own share of dismissal. The Pleasure Garden incident of 1948–51, when the CSA and the City Council reject the purchase/donation of Frances Hodgkins’ painting Pleasure Garden, acts as a high-water mark for this rift in the arts.

Glover and Angus both leave after personal crises. Glover’s alcoholism leads to his dismissal from Caxton, and he takes a printing job in Wellington. Angus moves north in 1953 – first to Mangonui in Northland, then to Wellington. Curnow is appointed to a position at Auckland University College. Bethell passes away in 1945.

In the end, only a few are left. Bensemann stays. So does Lusk, who joins a group of new teachers at the School of Fine Arts, which in a few years includes Bill Sutton, Russell Clark, Don Peebles, and Rudi Gopas. New students follow, including Patrick Hanly, Bill Culbert, Jacqueline Fahey, and Trevor Moffitt. Like Angus, Bensemann, and Baigent before them, they socialise and live together in flats around the city (this time on Armagh and Rugby Streets).

In part, Bloomsbury South reconstructs a lost Christchurch, as the urban fabric of that time has changed so much. The book represents a superhuman achievement for Simpson. His writing is lucid throughout, and to bring so many narratives together, interlocked as they are, is an impressive feat.

But the book also raises questions about the sorts of things we choose to remind ourselves of in the face of forgetting. Unassailable stacks of books and articles have been published on what is covered here, many by Simpson himself. And if this publication is a capstone, it still leaves gaps. Artists such as Henderson, Jacqueline Sturm, Theo Schoon, and Anne Hamblett are largely passed over, despite the book’s breadth and depth.

It seems that this happens because they do not fit into Simpson’s narrative. For instance, Schoon’s interest in Māori art and culture highlights a lacuna among a supposedly aware group of artists. The perspective of Sturm, a young Māori poet and writer, amidst a group of Pākehā artists would have been an interesting counterpoint for Simpson to explore. Instead, she is a footnote in Baxter’s story as his wife. Hamblett, a painter who studied together with McCahon and Lusk in Dunedin, is similarly cast as McCahon’s wife.

Henderson, a French-born and -trained painter, is name-dropped a few times, and her Plain and Hills and Arthur’s Pass are reproduced as comparisons to Angus’ Cass paintings. But Simpson stops there, and it is a shame, because her way of seeing is so clearly different; her landscapes seem dark and perturbed when compared to the ebullient mountains of the Cass works.

In 1949, at a time when Simpson argues that the cultural scene is just beginning to fade, Vivian Lynn finds Christchurch “dull, absorbed in middle-class notions of class and breeding, and nineteenth century in outlook”. This might be an opinion shared by many in Bloomsbury South, but, for Lynn, something new was starting. Entrance to art schools was opening up. Classes were becoming more socially diverse. Teaching styles were changing. People like Sutton and Barbara Brooke were helping to enable new collectives to form, complete with spaces like the arts journal Ascent (co-founded by Brooke and Bensemann), the Brooke Gifford Gallery, and Sutton’s own house and studio.

It is perhaps inevitable that Simpson overlook some things, and certainly what he does address in Bloomsbury South is discussed with much intelligence, attention, and care. The time period was extraordinary; but it is held in nostalgia, heightened by the difficult state Christchurch is in today.

For Simpson, what makes the time unique is that it gave Christchurch “national leadership”. He argues that this was the only time that the country looked to Christchurch for the conception of its collective identity. However, the space once occupied by Bloomsbury South continues to be taken up and made anew. Successive artists have lived here and formed the same kinds of scenes and networks that have, in their turn, broken apart.

Living here throws into relief the reality that despite so much change every day in front of our eyes, so much stays exactly the same. Rather than Yeats’ “all changed, changed utterly”, maybe a better quote would have been the last lines of Bethell’s ‘Response’:

But oh, we have remembering hearts.

And we say ‘How green it was in such and such an April,’

And ‘Such and such an autumn was very golden,’

And ‘Everything is for a very short time.’

Main image: Leo Bensemann, Frontispiece for Allen Curnow’s Not in Narrow Seas (1939).

Bloomsbury South: The Arts in Christchurch 1933–1953

Auckland University Press, 2016, RRP $69.99

Available from Unity Books and other good bookstores