Idiosyncratic Man O’War: A review of Blood Ties

Vaughan Rapatahana reviews Blood Ties by Jeffrey Paparoa Holman and finds a potent and engrossing collection, but one that will possibly enrage.

Vaughan Rapatahana reviews Blood Ties by Jeffrey Paparoa Holman and finds a potent and engrossing collection, but one that will possibly enrage.

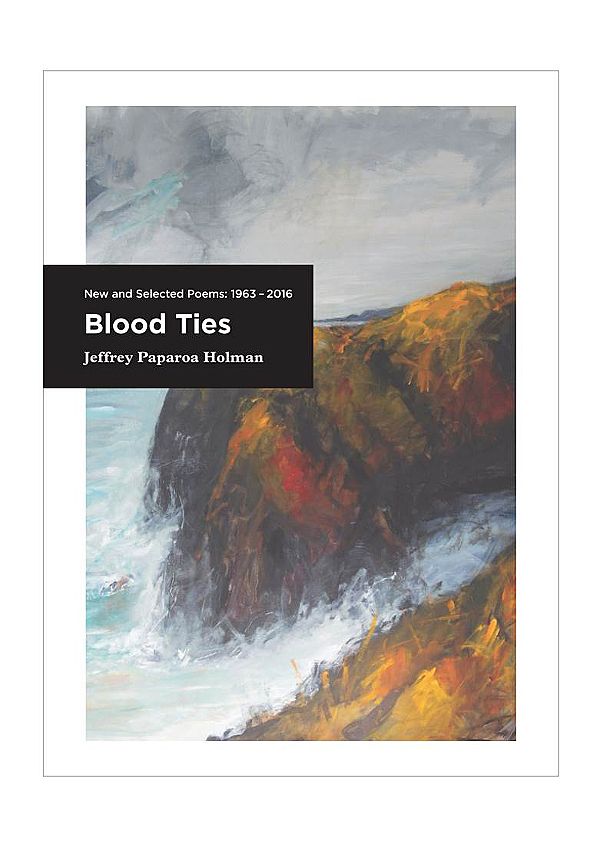

This is a comprehensive collection of poems by Jeffrey Paparoa Holman from 1963 to the present day and as such is rather a thick book running to 167 pages, including notes. Most poems within have been published elsewhere, although there is a selection never before seen. Divided into eight separate sections, Holman nevertheless tends to concentrate on similar topoi or themes throughout the entire book.

More, given that the collection is a lifelong symbiosis of his work, he seems rather embroiled in his past and many poems reflect events of long ago, such as two World Wars and their associated military paraphernalia; as well as the poet’s own upbringing in West Coast, South Island, Aotearoa New Zealand – after having emigrated to these shores when still a young boy, with his father ‘fucked up by war’ (from ‘Mary at dawn, April 2004’). Blood Ties, the book, is romancing the past – rather like the Blackball bridge, which Holman designates as, ‘I’m the bridge to the past’ (from ‘sonnet xxiii’).

What then are these topoi? Other than war and the associated ‘wall of torpedoes’ (from ‘Wall’), guns, aeroplanes and so on; there is an entire section on Europe during war and in the aftermath of it. There are mines and mining disasters; several dead poets; Holman’s dead father; some idiosyncratic features of the West Coast, as well as a stress on New Zealand’s natural and avian surroundings – which the poet has an obvious empathy with.

Me he arotahinga ki te ao Māori [And a focus on the world of the Māori] – which Holman has had considerable inculcation in and knowledge of, thus his incorporation of te reo across several poems, indeed in, several of his better poems, such as the fine pair originally published in Maori and Indigenous Review Journal, when I was poetry editor and nagged him to submit. These are ‘E kōrero ana ki Ngā Tama Toa/Talking to the young warriors,’ and ‘Dreaming of Te Rauparaha.’

He is often at his best when he espouses Māori cause, extols Māori. Indeed, I would categorise Holman – as what my Tokoroa workmate Trevor Bentley has so well depicted – a quintessential Pākehā-Māori, who, just like Holman, were British expatriates who adopted an alien culture in defiance of their own existentially unsatisfactory one, in a process of ‘disavowing British cultural hegemony,’ as Merana Mita once put it. His manawa – or heart – beats much more strongly when addressing historical injustices and iniquities imposed on Māori and on subsequent efforts by Māori to redress some of these slights and plights. Thus his curious hybrid Allen Curnow – Aroha Kohu Rau persona in, ‘The secret life of Arana Kohu Rau.’

There are constant echoes of James K. Baxter here, to the extent that I am instantly reminded of the title of a similar-period Jefferson Airplane LP – ‘After Bathing at Baxters’! So we delve into lines such as these from, ‘On looking again into Heemi’s’:

you sing in praise of the twisted ones with their nerves

of steel, who ride to the factory comatose for another

day at the same old wheel

Which leads on to my next point: Holman is ever the proletariat proxy, an archetypal Kiwi Bloke working class man, ever defiant about the Tory boss striate. As such, his work is often angry, especially about preventable mining mishaps such as at Strongman in 1967 and Pike River in 2010, and often soaked in the same beer swilling pub and RSA ethos of the men he writes about – again generally embedded deep in the past. There is here a pervading patina of death, traumata, decay, and more than some bitterness. Often items within lines are broken, forgotten, obsolete and the lines themselves shards, barbs, ostracons. As witness this example from ‘I-Ching coin jade padlock’: 'Weatherboard wards with rotting eaves.'

Would I say Holman has a chip on his shoulder? Often in this collection, yes and yet more often than not, justifiably, methinks.

Would I say Holman has a chip on his shoulder? Often in this collection, yes and yet more often than not, justifiably, methinks. However at the same time I would say that he also positively grasps male camaraderie and the bonding of fellow labourers in their abiding antipathy to, ‘Tory ministers [and] do-nothing Lefties,’ (from ‘Check inspector’). He also has a resilient and abiding blood tie to te whenua [the land] – as exemplified in ‘Papatipu kissing me.’ Here are opened the most visceral of Holman’s veins. His excellent self-epitaph, ‘Resurrect me in the rain’ reminds me of this whakataukī:

Te toto o te tangata, he kai; te oranga o te tangata, he whenua.

[The blood of man (is from) food, the sustenance of man (is from) land.]

More, he can certainly – occasionally, at least – pen a paean of hope, as in ‘For Raine 7.5.74,’ which has to be the most totally positive poem in the book, even given the weird reference to the new born girl as a ‘female mammal.’

Over and above all else, the resonant presence in this book is of good keen men, and the Crumpean reference is deliberate. This is a particularly male-oriented selection of poems and themes, full of accolades to Holman’s mentors such as Peter Hooper and to fellow (often expatriate) poets such as Brodsky and Gilbert, while Curnow, Baxter again, and Tuwhare are also comrades in the cabal.

Several poems are dedicated – to men. Man worship is a term I would utilise here, for women... are scarcely visible anywhere at all.

Several poems are dedicated – to men. Man worship is a term I would utilise here, for women – other than the poet’s brave mother and one empathetic snippet regarding Michele Leggott in ‘it will sound’ – are scarcely visible anywhere at all, except where they are the victims of bashings from drunkard spouses. As in the rather worrying poem ‘T-bar clothesline, Okarito,’ whereby the clothes line outside seems to engender more empathy than the battered wife. The last bathetic line is:

And it’s marvellous drying weather.

In so doing, Holman seems to completely abnegate the terrified woman he had so clearly depicted earlier:

her wet panties

pissed in fright

when the back door

locked to keep him

out for the night

caves in

In this masculinity into infinity regard, he reminds me of military man Stephen Daltrey’s recent novel. Coming Rain, in which hard-bitten men alone a la Mulgan, rule rampant their roosts and women are cast more as frivolities, if even cast at all. Blood Ties is ripe with men defining, even deifying, other men. Thus:

And that line: ‘It wakes them up, baffled in the middle

of their lives, out of ‘The History of Men’

from ‘Said, Jack,’ which strongly echoes Thoreau’s statement, ‘the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.’ And then from ‘Check inspector’ there is:

So what the hell is a man? so what the hell is a man?

At the very least, this is patriarchy at play. I am instantly reminded of what Lloyd Jones once penned about poet Alan Curnow, namely, ‘his work generally does not so much denigrate women as insistently foreground predominantly masculine concerns.’ Doesn’t such ‘complicit masculinity’ say something rather alarming about some New Zealand literature?

These... are fine poems, up with the best in the extensive Aotearoa pantheon of male poets writing about their dead pater.

So it is no surprise that it is Holman’s father who is the subject of the strongest work here, as in ‘Father and son,’ and ‘As big as a father.’ These, too, are fine poems, up with the best in the extensive Aotearoa pantheon of male poets writing about their dead pater – see Sam Hunt as another such exemplar.

Holman’s writing style is never near postmodern in technique or any of its clever apparent non-content. He is a ‘conventional’ writer if you will, more focussed on stanza and verse, even if he can and does write experimentally at times, as with his shape poems, such as ‘when you all,’ and the self-minimalising ‘The last Huron language speaker.’ Indeed, he is well aware of –

when the lines do not begin and end like a real poem

a proper poem a gracious ordered sinuous well-behaved poem

(from ‘when you all’)

Thus his tutū with conversations (see ‘Poem for John Pule: the last days of Peter Hooper’) and couplets (see ‘Inferno (Strongman mine, 1967)’), and repeated waiata-like line intros (see ‘After the tremor’). There are the constant repetitions of phrases and words in any given poem, as well as his brief, terse, concise outlines of striking images, such as ‘Bach life.’ All of which reflects rather a distinctive personality with all of his poetic pistols drawn and cocked: an often aggrieved poet on a mission, namely to write/right wrongs in a determinedly no-holds-barred, outspoken and sometimes abrasive fashion.

Possibly dated in some ‘modern-as-postmodern’ poets’ definition of the term as regards his technique and his subject matters, Jeffrey Paparoa Holman nevertheless has to be read, has to be admired for the sheer strength of his passion and – above all – for the sheer skill he presciently presents as a Kiwi poet: Blood Ties is plump proof of his lifework. This man’s man can write potent poems, replete with evanescent and effective sound and vision, as in the examples to follow, which reflect his distinctive poetic mantra (from ‘Dark with nouns’) of,

find your own nouns…drink with a verb as you would with the sexton

Thus we sight and breathe such lines as from ‘Inferno (Strongman mine, 1967)’:

He showed us the vast theatres of oblong space

like cavities in the dead black teeth of giants

and from ‘Memoir’ –

If only the leaves could tell the whole story, before

they fall and strip the naked branches speechless

and from ‘Tuna,’

The days migrate like fish…

I feel words slither

between my legs in a moonlight

creek.

As an anonymous writer notes on the cover blurb, ‘Poetry and song have their own healing gifts: here Jeffrey Papamoa Holman calls on their potency to set the mind free.’ Holman will feel well-liberated with the publication of this idiosyncratic man o’war, while readers will become engrossed, engaged in and perhaps slightly enraged by, but certainly ever embroiled in, his many hardboiled and variegated battles.