What Makes A Story? Considering Black Marks On The White Page

Jackson Nieuwland reads Black Marks On The White Page and asks himself, what makes a story?

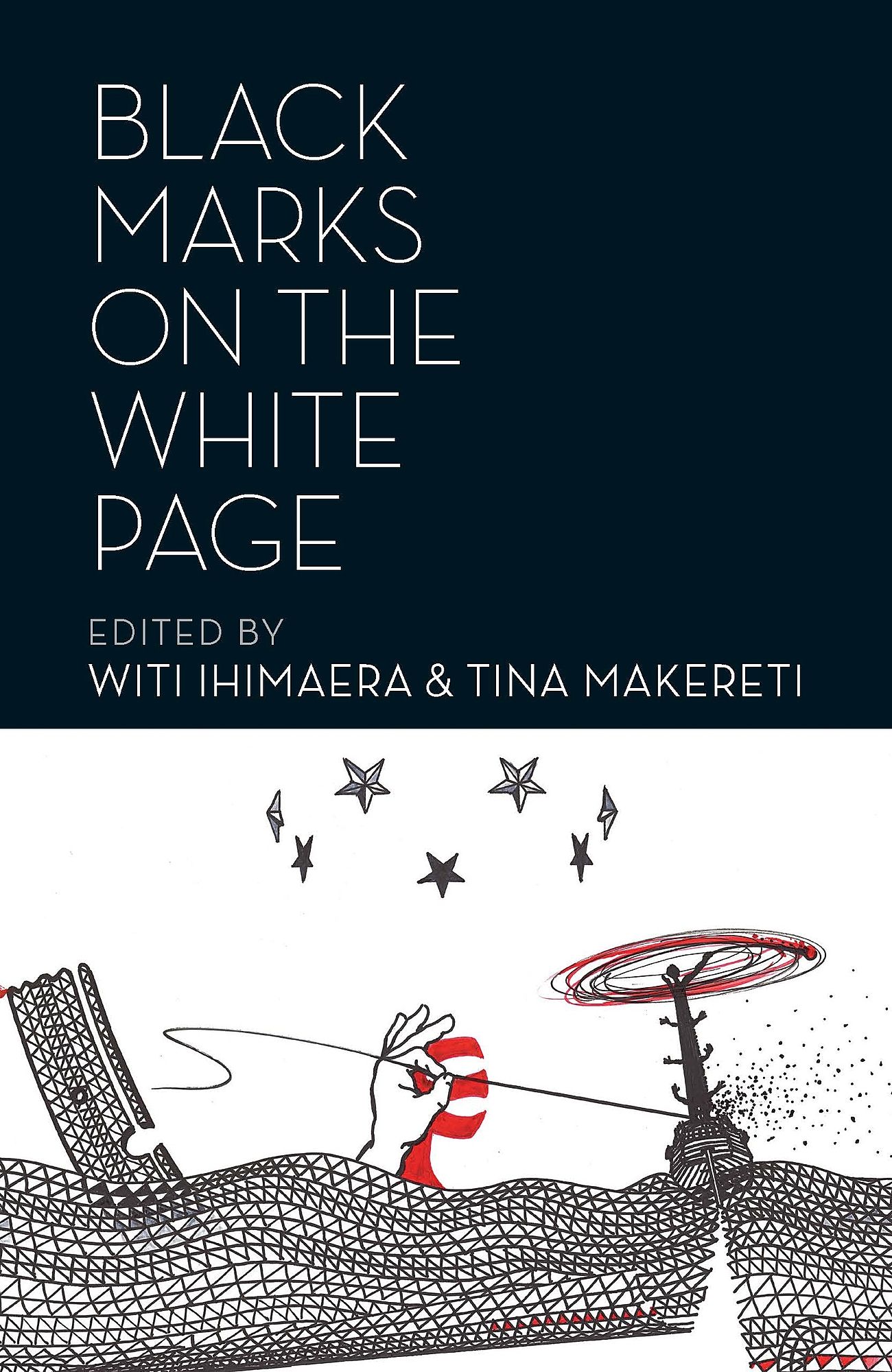

Jackson Nieuwland reads Black Marks on the White Page, an anthology of painful, sharp and funny 21st century stories by Māori and Pasifika writers. Nieuwland finds an engrossing and masterful anthology that makes him think about nature of stories – their shapes and purposes.

Earlier this year I had lunch with a friend. He had recently read Courtney Sina Meredith’s new short story collection, Tail of the Taniwha, and he told me that he enjoyed it, but that it was poetry and not stories. Soon after that I read the book myself. It’s one of my favourite books of the year and, in my opinion, very much a collection of short stories, though many of them stretch the boundaries of the form. One of the stories from that book, ‘The Coconut King,’ is included in Black Marks on the White Page.

The version of ‘The Coconut King’ in Black Marks looks different from the one in Tail of the Taniwha. Instead of being presented in verse, it is printed as a prose block with the sentence fragments separated by backslashes. This changes how the story reads, making it feel more staccato, with the phrases cutting off abruptly rather than flowing smoothly into one another.

I asked Meredith about this change when interviewing her about Tail of the Taniwha. She told me, “The way it is in Black Marks was how I wrote it initially and then [Beatnik designer] Kyle put forward the proposition for how it is inside of Tail, and it really worked for me because it gave the lines all of the air that they truly needed…I think in future I will always send out the initial version if it gets printed elsewhere. The special difference in space within Tail for that particular story means a lot to me.”

In their generous and rich introduction to Black Marks (which discusses the collection much better than I could ever hope to), Tina Makereti and Witi Ihimaera mention asking Meredith about the form of this story. She told them, “I don’t know…I think it’s in the va.” So the piece occupies the space between fiction and poetry, the centre of the Venn Diagram; it is not just a poem or a story, it’s both.

*

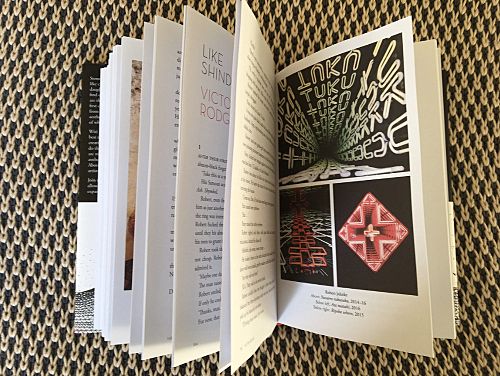

My favourite thing about Black Marks on the White Page is the editors’ inclusive approach to what constitutes a story. Most anthologies of stories focus narrowly on the ‘short story’ form, a very specific type of writing, but that is just one way of telling a story. By including pieces like Cassandra Barnett’s series of monologues ‘Pitter patter, Papatūānuku,’ Albert Wendt’s fiction in verse ‘Nafanua Unleashes,’ and a still from Lisa Reihana’s ‘in Pursuit of Venus [infected],’ Makereti and Ihimaera acknowledge the existence of many types of storytelling, which include traditional Pasifika forms and new experimental approaches.

Not all stories look like stories after all. David Geary’s ‘#WATCHLIST’ takes the form of a confidential government dossier of transcripts from flagged communications. Sia Figiel’s ‘Extract From Freelove’ includes vocabulary lists, a school report, and a ranking of the ‘TOP 20 BEST SONGS OF 1985.’

That said, I would have liked to see an even wider range of forms represented in the collection. Black Marks includes work by playwrights Victor Rodger and David Geary, but both of their contributions are prose pieces. As much as I enjoyed their contributions, I would have loved to have seen their scripts included. Similarly, there are more Māori poets with stories to tell than I could possibly list: Hinemoana Baker, Robert Sullivan, and Apirana Taylor are just the first few that come to mind.

Another recent anthology, Three Words, showed that New Zealand women are producing a plethora of high quality comics. Perhaps there could have been space to include work by Jessica Hansell or Susan Te Kahurangi King in this collection as well. And speaking of Jessica Hansell, what about musicians? If Bob Dylan can win the Nobel Prize in Literature, Anika Moa or Mareko could be included in an anthology of Pasifika stories.

The introduction to Black Marks asks whether some of the pieces in the anthology are ‘fiction or non-fiction? Does it matter? Or, at least, how much are they one and the same?’ I’m in complete support of this kind of blurring the lines between genres, but the stories in the collection are presented as fiction. Pieces like ‘Great Long Story’ by Paula Morris and ‘Famished Eels’ by Mary Rokonadravu feel as if they are based in autobiography, but it would have been nice to see some explicitly true stories – an essay by Ines Almeida, or an excerpt from one of Ihimaera’s memoirs.

My favourite thing about Black Marks on the White Page is the editors’ inclusive approach to what constitutes a story.

None of this is to say there’s anything wrong with the traditional short story form. Patricia Grace’s ‘Matariki All-Stars,’ the story of a father struggling to raise his seven daughters after the death of their mother, is a joy to read, as is Gina Cole’s ‘Black Ice’ in which we follow Passang, a sherpa working on Fox Glacier. These pieces ground the collection, and I’m not sure how the book would hold together without them.

Admittedly, if Makereti and Ihimaera had followed all of these suggestions the anthology would probably have doubled in size and been difficult to fit together cohesively. As it stands, the book is exceptionally well balanced, and the stories are sequenced masterfully. Makereti and Ihimaera have done a superb job and should be applauded. It’s just that my instinct is always to push towards the eclectic and unconventional.

*

The pieces in Black Marks that worked least well for me were ‘We mobs got to start acting locally. Show whose got the Dreaming. The Laaaw’ by Alexis Wright, and ‘Tribe My Nation’ by Déwé Gorodé. Both are excerpts from longer works, and therefore parts of stories rather than whole narratives in their own right. These pieces were a struggle for me as a reader, and their incompleteness left me dissatisfied. Perhaps they work better in their original contexts, but here they felt confusing and out of place.

Of course some extracts are able to stand alone, and some stories are made up of a bunch of smaller stories. I’m thinking here of the books of Scott McClanahan, a West Virginian novelist whose autobiographical fiction is made up of short, mostly mundane and humorous anecdotes, which build to create moving and emotional novels. In Black Marks, Tusiata Avia’s ‘I Dream of Mike Tyson’ and Anya Ngawhare’s ‘King of Bones and Hazy Homes’ operate in the same way, working well as short stories in their own right.

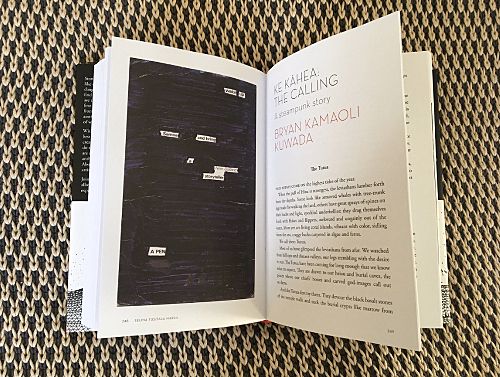

Selina Tusitala Marsh’s ‘Pouliuli: A Story of Darkness in 13 Lines’ is part of a story in a different way, and creates a whole story using pieces plucked from another. She has ‘taken a black vivid marker / pressed it against your page / and letter by letter, word by phrase / inked across your lines,’ and turns prose into verse using the technique of erasure in the tradition of great storytellers like Tom Phillips, Mary Ruefle, and Jonathan Safran Foer.

*

Reading Black Marks on the White Page made me think about the nature of stories, and their shapes and purposes. It reminded me of the claim that there are only three types of stories (or seven or eight or thirty six) and that every story can be categorised into one of a handful of archetypes. I haven’t studied the shapes of stories outside of my personal reading, but I know that Black Marks contains more than three types of stories. Tell me, how would you categorise ‘Pitter patter, Papatūānuku,’ because I have no idea.

I was also reminded of Jean-Luc Godard’s quote: ‘A story should have a beginning, a middle, and an end, but not necessarily in that order.’ This made me think about another of my favourite reads this year: Here by Richard McGuire, a graphic novel in which every page shows the same location at a different point in time. While it spans from 500,957,406,073 BC to 2313 AD, it certainly doesn’t have a beginning middle and end. I like to think of it as a shapeless story.

Can anyone point out the beginning, middle, and end in ‘#WATCHLIST’ to me? I can’t quite seem to find them.

A writing teacher once told me about a similar storytelling project, the art film The Clock by Christian Marclay. The film is a 24 hour collage of clips featuring clocks from famous films and television shows. There is no plot, just the passage of time from midnight to midnight. My teacher said it was the most compelling narrative she had ever experienced. Likewise, can anyone point out the beginning, middle, and end in ‘#WATCHLIST’ to me? I can’t quite seem to find them.

The rules people try to enforce and the walls they put up between different genres and forms fall apart when faced with the diversity of these stories.

*

Jione Havea’s piece ‘The Vanua is Fo’ohake’ is just as much a philosophical case study as it is a story. In it he explains the concept of talanoa, a conversation or ‘telling story,’ using the example of three men discussing the various meanings of the word ‘vanua’ (land, place, country, district, village, people…). Makereti and Ihimaera also use the term talanoa when describing Black Marks. The pieces in the collection are in conversation with each other, sometimes quite directly like Selina Tusitala Marsh’s ‘Pouliuli: A Story of Darkness in 13 Lines,’ which is an erasure of a novel by fellow contributor, Albert Wendt, or Whiti Ihimaera’s ‘Whakapapa of a Wallpaper,’ which tells the story of the wallpaper which Lisa Reihana’s panoramic video ‘in Pursuit of Venus [infected]’ is based on. Other times the conversation is more dispersed. For instance, many of the pieces included in the anthology discuss the differences in value systems between generations and cultures.

Makereti and Ihimaera also use the term talanoa...The pieces in the collection are in conversation with each other.

A similar conversation takes place in the film Waru, which screened this year at the New Zealand International Film Festival. The film is made up of eight vignettes, with a different female Māori director responsible for each one. Each of the vignettes follows a different character, all of whom are connected to the death of a young boy who was killed by his caregiver. In this way, the filmmakers engage each other in a conversation about child abuse, grief, and tradition.

Of course, when a book (or any work of art) takes the form of a talanoa, the conversation doesn’t end upon publication. These stories talk to us about family, politics, history, sexuality, religion, and much much more. Once you’ve listened to what they have to say, it is your turn to respond by filling more white pages with black marks.

Black Marks on the White Page is available from Penguin Random House.