Believing in 'New Zealand': The South Island Myth revisited

Michael Grimshaw on three Southern writers in the wilderness.

The real prophets of our time are those whose sensitive minds can grasp what adaptation means in emotional and personal terms, and express in their writings the vital struggle of man with his environment.

– Allen Curnow[1]

… This is my holy land

Of childhood. Trying to comprehend

And learn it like the features of a friend…

– Basil Dowling, ‘Canterbury’[2]

A different country…

When I left the North Island and came to the South to live, I felt immediately and overwhelmingly that I had come to quite a different country… I had come to what could have been a continent, from places that could only be an island. Here was the dryness of continents, the vastness, the shape of country that could go on and on… immediately in the South Island I sensed this strangeness, as if I had stepped into a world of a different order, the meaning of which I could not grasp.

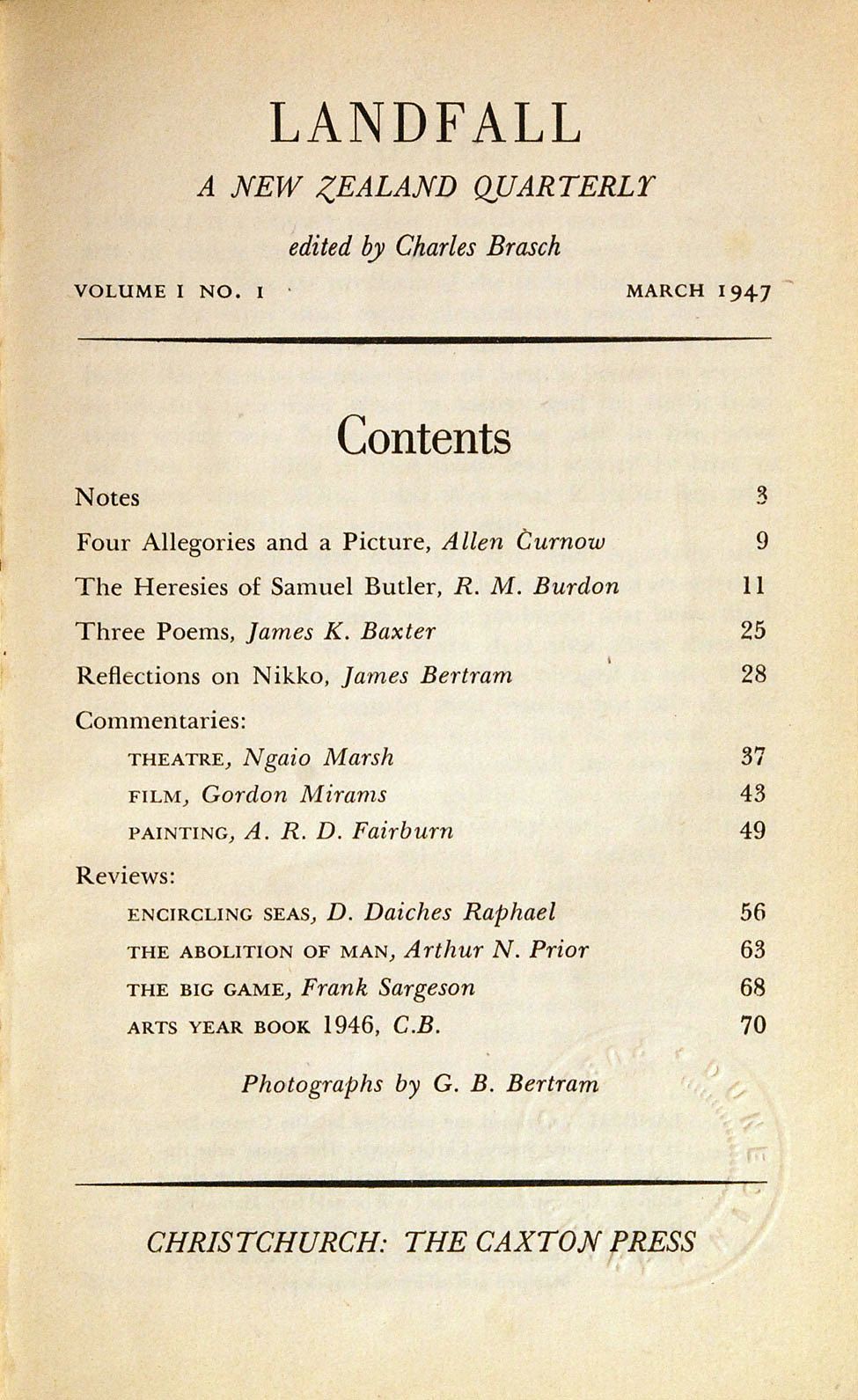

These words are from the opening passages of T. H. Scott’s ‘South Island Journal’, the record of his search with Theo Schoon for Māori cave drawings in the South Island interior. It was published in Landfall in 1950,[3] and reprinted in founder Charles Brasch’s personal anthology, Landfall Country.

From the 1950s, the ‘South Island Myth’[4] that Scott intimated became a ‘dirty phrase’, often taken to speak of some masculine Pākehā provincial essentialism that children, born in some marvellous years, left behind as they learnt the trick of standing upright here (to mangle Allen Curnow’s famous poem). It has been taken as a predominantly literary experience, or dismissed as the vestiges of landscape romanticism and the pathetic fallacy – ‘colonialism above the snowline’, as John Newton termed it in 1999.[5] That is, using the landscape to reflect internal states of the poetic observer.

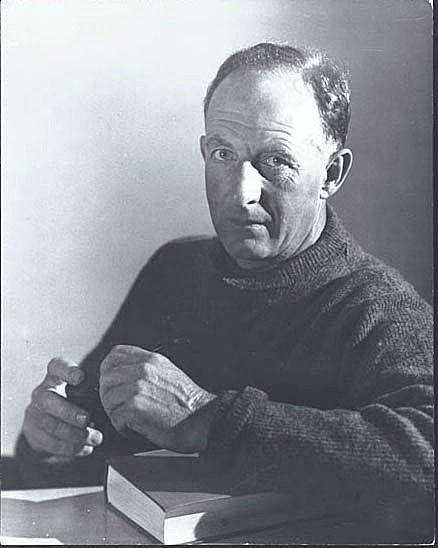

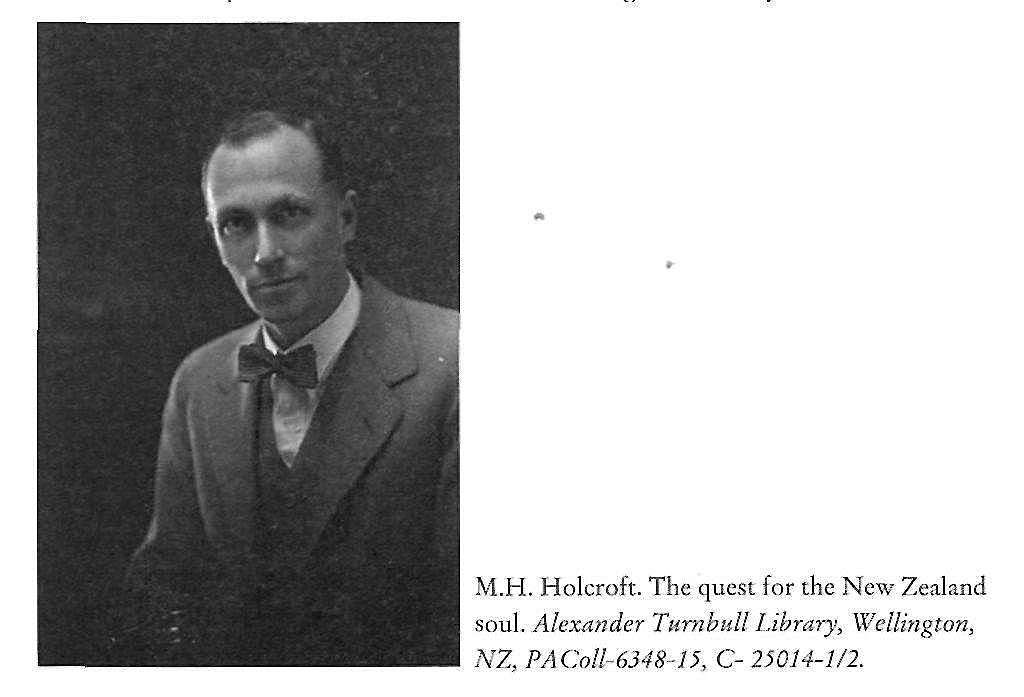

Here, I want to argue against half a century of literary critique in favour of the South Island Myth &ndash or rather, in favour of what it symbolizes. Not as a literary event – but rather in favour of what I take to be its central element, the issue of how and what to believe, in New Zealand. In particular, Charles Brasch, Monte Holcroft and Allen Curnow attempted something important, something we have been too quick to dismiss, because we have been too quick to read the myth in literary, not religious terms.

Brasch, Holcroft and Curnow didn’t go unobserved at the time. John Lehmann, editor of the mid-century series New Writing, noted from afar that something was happening down here, remarking in his autobiography:

… why was it then that out of all the hundreds of towns and universities in the English-speaking lands scattered over the seven seas, only one should at the time act as a focus of creative activity in literature of more than local significance, that it should be in Christchurch, New Zealand, that a group of young writers had appeared, who were eager to assimilate the pioneer developments in style and technique that were being made in England and America since the beginning of the century, to explore the world of the dispossessed and under-privileged for their material and give their country a new conscience and spiritual perspective?[6]

For our discussion, it is the concluding phrase of Lehmann’s statement that is most important, the desire to “give their country a new conscience and spiritual perspective.” This unconsciously echoes Brasch’s challenge in his ‘Notes’ to the first issue of Landfall in March 1947. In discussing the location of New Zealand and especially its potential to create art and its possibility to act as a centre in its own right, Brasch states:

… what counts is not a country’s material resources, but the use to which they are put. And that is determined by the spiritual resources of its people.[7]

What is forgotten in the dismissal of the South Island Myth (or perhaps not) is that it was, at heart, an issue of spirituality – of spiritual location, and of spiritual dislocation.

*

The South Island Trinity

All three proponents of what came to labelled the South Island Myth had a strong religious core to their outlook. Curnow was the son of an Anglican clergyman and briefly trained at St John’s Theological College in Auckland. Doubts forced him to return to the world of journalism from which he had fled. Yet, in leaving God behind, he could not leave God’s absence . In the 1930s and 1940s especially, his poetry and criticism was focused, implicitly, in the issue of identifying and locating ‘the spiritual resources.’

As the literary power balance shifted north, the South Island was reduced to the provincial wilderness: real life happened in cities, in the north – and was secular.

Unfortunately, more has been made of Brasch’s posthumous outing than of his ethnicity and how it impacted his life’s experience and work. Yet as any reading of his poems, journals and his autobiography make clear, central to his outlook was his Jewish identity – and the childhood theosophical environment. A believer without God, his spiritual searching for location is the core of the Landfall ethos under his editorship.

Meanwhile, Holcroft became the public face of a form of civil spirituality that was as derided as it proved attractive. Drawn to mysticism and Jung, his quest for a New Zealand identity was likewise read through a spiritual search and questioning. All three, together, became associated with what the rampantly secular Keith Sinclair termed, dismissively, the “South Island school”.[8] From the 1970s, critics have been especially harsh, seeing landscape as yet another romantic fallacy that needed to be cleansed by modernity, or dismissed by postmodernism and deconstruction. As the literary power balance shifted north, the South Island was reduced to the provincial wilderness: real life happened in cities, in the north – and was secular. Spirituality, if allowed, was Māori, and reduced by outsiders to an uncritical essentialism.

*

The origins of the myth?

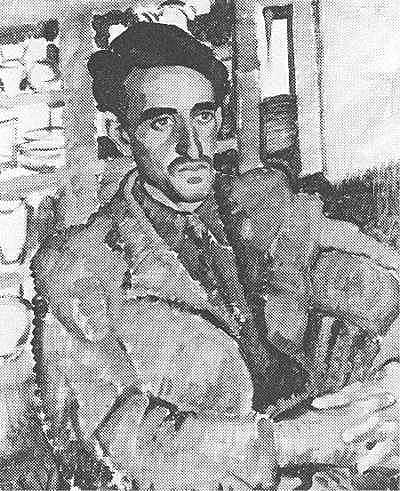

When we read back in New Zealand literature, I believe we can trace the basis of the South Island Myth to a most unlikely source – the Aucklander A. R. D. Fairburn, who, exhibiting that most common of North Island provincial outlooks, had sought an OE in England in the 1930s but cheerfully could note to Brasch in 1946, “I’ve never been to the South Island.”[9]

In 1934 Fairburn published an essay in Art in New Zealand entitled ‘Some aspects of New Zealand Art and Letters’. I want to argue (perhaps completely heretically) that the South Island Myth is a reaction to this piece (at least in part), which I term a form of North Island Myth. In this article are to be found all the elements that Brasch and Curnow come to argue against, while Holcroft, somewhat paradoxically, can be seen to take the arguments as his starting point.

Fairburn’s central point is that of what I term the ‘dislocated exile’ and his claim is as follows:

We are of British seed, planted not so very long ago. We have, as we are never tired of pointing out, no tradition of our own. In a word, we are Englishmen born in exile. Set down in this evergreen unchanging countryside, there is constant pain in our hearts, a nostalgia for the vast movements of the English seasons, for the honey-coloured haze that shrouds the northern landscape on even the brightest summer day, for the intoxicating beauty of springtime in England, and for the endless melancholy of autumn. These motions of the earth and air we are lacking, except as a pattern in the blood, which finds no correspondence in nature. A dynamic race in a static environment: stagnation will precede, and cloak, adaption.[10]

Fairburn carries on to note all the usual nationalist tropes: seasonal disjunction, nature-worship, the hard-light thesis and the sacred-mythological task of the young New Zealand writer of the time to “… by his creative energy, give life form and consciousness.”[11]

It is against this North Island Myth, the green exile, the land without seasons, the exilic Englishman, and the static environment that Brasch and Curnow write. Holcroft occupies a place between, taking these sentiments as a starting point to locate a new mythology of New Zealand, yet, always aware, with deference to Fairburn, of seasonal disjunction.

*

Brasch’s Holy Land

For Brasch, these southern hills were representative of that other Holy Land – but whereas that was a land of presence, this was a land of absence where man not God makes and marks meaning. In March 1941, writing a requested piece in John Lehmann’s Geographical Magazine on “New Zealand, Man and Nature”, Brasch begins by stating the temporary, provisional and rootless nature of European settlement, where nature (originally by necessity and now by force of habit) is treated as an enemy.[12]

Two important themes come out of this piece. The first is a type of animist encounter with the land, a theosophical panentheism.[13] The second is a form of pathetic fallacy, but – and this is crucial – the pathetic fallacy for Brasch is always personal, not societal. In Indirections, Brasch, sitting in Queenstown Park under trees planted by his grandfather decides to make art (being a writer and a poet) his life. The stones there provide his model:

… these must be my exemplars, if natural objects could be; patient, wholly themselves, enduring.[14]

So, the South Island Myth of Brasch is that of the silent, empty, waiting land as a metaphor for Brasch himself. What critics take as the universal is really, for Brasch, the personal.

It could be read that Brasch’s totem is the poplar, transplanted from the Mediterranean, the centre of civilisation, now marking a newly emptied land. As he writes:

The Lombardy poplar is man’s happiest gift to New Zealand: it is nowhere lovelier than in the more arid parts of Central Otago, from which all the native bush has gone.[15]

This sense of a flowering in the desert has distinct Old Testament antecedents. For Brasch, the South Island interior was a new Judea, a new promised land that spoke of promise and yet absence. Brasch’s most explicit stating of this premise occurs in his ‘Notes’ for Landfall in September 1950. Here he takes on the critiques of “South Island romanticism”:

… in particular by volatile Aucklanders dazzled by the notion of New Zealand as a new little America…[16]

Noting (in reference to his Geographical Magazine article) that “Every civilization is in one aspect the expression of an accommodation between man and natural forces…” Brasch makes the comparison with William Wordsworth in a manner that explicitly frames Brasch’s response to the land as a faith(less) statement:

In the crisis of his middle life, Wordsworth came to identify the power he felt in and behind nature with the God of Christianity… One may feel that he should have been strong enough to strike out into the wilderness that faced him, to endure nihilism, to come to terms – if he could – with the problem of evil.[17]

Here, we have Brasch the modernist. The South Island interior was the physical expression of the emptiness, the power of nihilism writ large. The indifference and lack of meaning of the empty land meant meaning had to be wrestled with and out of – written into and out of – the land. As the French thinker on technology and theology, Paul Virilio states of his own position:

… like Jacob, he wrestled with the angel of technology not to prove his disbelief, but to prove his freedom to believe.[18]

Brasch wrestles with the land, his Jewishness, his theosophical childhood, his sense of exile (Modern, Jew, European, agnostic), his whole identity to locate himself, to win the blessing of the land and of the location. The Myth is that the personal search will reflect something of the wider, national search. It is here that the critics have got Brasch all wrong. Yes – there is a form of pathetic fallacy occurring. But in the end, it isn’t a matter of simply foisting one’s internal feelings onto the landscape, but rather an existential one with the debate of nationhood as a whole.

*

Holcroft’s mystic myth

Holcroft too is obsessed with the idea of nationhood and national identity. He’s also the most overtly religious of the South Island mythologisers, a facet of his writing that gets repeatedly attacked by his critics. I want to argue that we can best understand Holcroft as the attempt to create community after the absence of God.

Holcroft may have been a nominal believer in his early life, but when on his OE in France in 1929, he had a mystical experience in a church in the tiny village of Garvanie, some sixty miles from Lourdes at the base of the Pyrenees. Holcroft notes he first climbed for two hours in the hills above the town, witnessing an avalanche before descending and entering the church. There, he had a brief bout of nature mysticism:

I thought I could feel, without any sense of the fantastic, that the larger church of the mountains had used this small building as a sort of repository and storehouse of its gentler moods.[19]

As he goes on to note:

For a long time, I suppose, I had been groping towards an understanding of religious experience, and its background in history. That evening, or soon afterwards, I began consciously to look for it.[20]

What Holcroft begins to look for is that lost community, that community that takes the place of the absent god. Holcroft notes what constitutes the lost community: an idealised past (generally of British, European provenance) whereby rituals and religion are organic. In this new land, the lost community has to be acknowledged before, it is argued, the new community can be built. Community therefore does become part of a search for communion, that sense of unity – yet, Holcroft asks, what will build this?

Holcroft’s approach is that of communication, of mythmaking. In his three major texts of the 1940s, The Deepening Stream (1940), The Waiting Hills (1943) and Encircling Seas (1946), Holcroft sets about creating a nationalist mythology that will restore some lost sense of the sacred to the emerging nation.

The naivety is perhaps incredible for us today to encounter, yet the claims to mythic essentialism Holcroft makes always prove popular, persisting in ahistorical ways to the present.

Holcroft’s trilogy has resulted in him being perceived as a secular theologian, a prophet of dislocation, the animist seer gazing fearfully on the primitive forest and wondering what may yet spring from – or across the encircling seas. The basis is itself derived from a form of South Island mythic essentialism, the South Island braided river bed that has many streams, yet ends united in the sea.[21] While Holcroft has often been critiqued for attempting to articulate a national soul, he is more circumspect, seeking to analyse if we are engaged “… in the task of shaping a soul”[22] – a crucial difference, for what Holcroft offers as possibility, others read as direction and proscription.

One of the striking and unavoidable takeaways for a contemporary reader encountering Holcroft’s texts is the degree to which, as a modern European in New Zealand, he views the indigenous forest as unnecessary – as primitive, as evil, as disordered, as chaotic.[23] Yet Holcroft is enough of a romanticist to seek some form of spiritual essentialism in a link with the land – but here, he often strays uncomfortably into forms of Volkgeist, claiming:

There can only be a doubtful future for a nation that neglects the soil… It is from the soil that life receives its sanction, its strength and its purity.[24]

Meanwhile, in Encircling Seas he is not prepared to dismiss idealism even though it has been “… perverted by the Germans and inverted by the Russians”. For, he claims:

… idealism, at its best, is an attempt to identify a racial soul with the processes of history, a consecration of soil and mind to the service of the spirit.[25]

The naivety is perhaps incredible for us today to encounter, yet the claims to mythic essentialism Holcroft makes always prove popular, persisting in ahistorical ways to the present. Bill Pearson’s contemporary warning in his 1952 essay Fretful Sleepers of the fascist impulse in New Zealand needs to be read through Holcroft’s populist construction of a Volkgeist. This is of course counter to the ethos of the South Island myth as expressed in Brasch, Landfall and Curnow – even though Holcroft writes in support of Brasch and Curnow’s articulation of the silent land, the strangers in a strange land ethos and the unknown country myth.[26] He does reference the Judean hills analogy implicit in both Brasch and Curnow, but again reads them as the location for an idealist purification, the thrust of which runs counter to Curnow and Brasch.[27]

*

Curnow’s anti-myth

It is to the third mythologiser, Curnow, that I now wish to turn. Born and raised in the South Island, he is perhaps the South Island mythologiser – but in the manner of Brasch rather than Holcroft. Curnow’s agnosticism is closer to Brasch’s position than it is to Holcroft’s Jungian-derived Volkgeist. As the story goes, Curnow flees from the wickedness of the world of journalism to study for the Anglican priesthood – his father being an Anglican clergyman. Doubts, however, force a reconsideration and (famously, symbolically) a fateful crossing of Cook Strait. Curnow returns south – working for the Press newspaper in Christchurch, he begins crafting his poems and later, his groundbreaking anthology that, in its introduction carves out a new national identity.

Curnow does acknowledge the debt he and others owe Holcroft’s attempt to articulate a national and nationalist consciousness – and the religious framework he takes. This occurs explicitly with the poem ‘To M. H. Holcroft’ from his 1949 collection At Dead Low Water & Sonnets:

… those foothills, Monte, where you found

Spiritual powers, but root and rock to grip;

For islands, an intelligible hope.[28]

Yet Curnow’s face was turned the other way from Holcroft’s – and indeed from Brasch’s. As James K. Baxter noted in 1951, for Curnow the desert is not primarily the interior of the South Island. Instead, his wilderness “is the Sea, the marine desert that which surrounds our island desert”, this wilderness being “the mirror and symbol of God.”[29] This latter point is important because it has become common to see Curnow as (in Mark Williams’s words) a “post-religious poet”.[30] Yet Curnow is not post-religious. He’s post-Christian, certainly, and secular, But if we take religious back to the Latin root religare – “to bind together” – then Curnow in this period is certainly religious.

Like the Israelite prophets, Curnow looks into the wilderness to find the absent god, to find the prophetic temperament and message that will challenge the orthodoxies of the day. As a critical modernist, God for Curnow is unnecessary, yet he is also wary of the community and nationalist identity proffered as a communal substitute. This is why his is the anti-myth, the myth of the wilderness, the emptiness of modernity, the instability of the socio-cultural desert that is the location of modern life – not, as T. H. Scott had noted, the North Island garden among the mountains.

Curnow as modernist sceptic is critical of the boosterist myth, the godzone myth, the Edenic myth and pushes for a fall – a fall into knowledge.

Baxter later misread Curnow in his 1967 Victoria University Wellington lecture ‘Aspects of Poetry in New Zealand’. Baxter strives to link the Curnow-influenced anti-myth of isolation with the Fall, claiming:

The myth of colonial isolation and inferiority seems to be connected broadly to the theological concept of the fall of Man – the immigration of ancestors was, as it were, a second Fall, a departure from a garden of Eden situated somewhere in Victorian England.[31]

I want to argue that Baxter is wrong – on two counts. Firstly, like many critics he misreads what is involved in the Fall, through a failure to take a close reading of the text involved, Genesis 2:15–3:24. Too often we read this as purely the story of temptation and disobedience. Yet this, according to the text, is not the reason for the exile. The Fall is a fall into knowledge, the exile into the wilderness of the world is because of the possibility this knowledge offers. From Genesis 3:22–24:

Then the Lord God said, “behold, the man has become like one of us, knowing good and evil; and now, lest he put forth his hand and take also of the tree of life, and eat, and live forever” – therefore the Lord god sent him forth from the garden of Eden, to till the ground from which he was taken. He drove out the man; and at the east of the Garden of Eden he placed the cherubim, and a flaming sword which turned every way, to guard the way to the tree of life.[32]

Secondly, he locates the second fall in the wrong place. The second fall is not a fall from England, but rather the fall of the anti-myth. If we look back at the nineteenth century boosterist myths of New Zealand, the language was commonly that this was a form of Edenic paradise, a new and unmarked promised land.

Curnow, steeped in the Old Testament and the King James version, as modernist sceptic is critical of the boosterist myth, the godzone myth, the Edenic myth and so, acting as secular prophet in the wilderness, pushes for a fall – a fall into knowledge. He has eaten of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. He sees the materialist fallacy of New Zealand life, and it is really the great theme of his poetic sequence ‘Not in Narrow Seas’.

Here, the wilderness stands against our materialist hopes for ease – a life that will give us the security of living for ever. The wilderness, the location of the absent god, is where time and the winds of change are located; the wilderness of the sea confirms our deserted status. Life is a godzone Tower of Babel that Curnow, as prophet, seeks to cause to fall. The anti-myth is the longing for exile so we can be free of the Edenic myth and free of the god of materialism and provincialism – a god as limiting as the jealous Christian god.

Peter Simpson notes some of this in his 1986 essay ‘The Trick of Standing Upright’, claiming:

In Curnow’s mythology the colonial is both expelled from the garden (separated from his true home) and is the spoiler of the garden he enters. To be a New Zealander, therefore, is to be trebly fallen (on personal, universal and national levels).[33]

Yet Curnow’s anti-myth embraces that fall, and seeking of the act of redemption that the fall engenders. It is a fall into a secular freedom, a fall that frees the emerging, naked nation to wander in the wilderness, free of the unnecessary ornamentation of god and godzone. He’s aware of this, locating his 1945 anthology as part of “our ‘spiritual’ – or call it ‘imaginative’ – history of New Zealand.”[34] Curnow goes as far to claim that:

Strictly speaking, New Zealand doesn’t exist yet, though some possible New Zealand’s glimmer in some poems and on some canvasses. It remains to be created – should I say invented – by writers, musicians, artists, architects, publishers, even a politician might help – and how many generations does that take?[35]

These are the religious underpinnings of the South Island myth – that New Zealand has not yet occurred. It is not providentially given but rather has to be created – spoken into being: Let there be…? In a secular, modern world, it is humanity who must make the wilderness flower.

Here again we must return to T. H. Scott. This awareness arises in the South because it was desert wilderness. The North, the gardens among mountains, took the providential line, the Edenic line. The South, Curnow and Brasch especially, take the line of Exodus – it is the experience of wandering in the wilderness that creates the nation that will become the land of milk and honey. Holcroft wanted to try to return to the national but fatally, he did so with an antipodean provincial urge to conjure up a Volkgeist. However, Brasch and Curnow were aware that as moderns, they had wilfully left the garden – and the wilderness had no god.

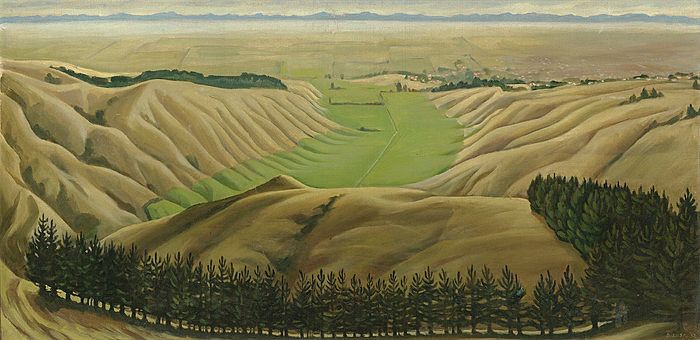

Main image: Doris Lusk, Canterbury Plains from Cashmere Hills, 1952.

[1] Allen Curnow, ‘Prophets of Their Time: Some Modern Poets’, in Peter Simpson (ed.), Look Back Harder (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1987), 19. It is noted that Curnow is not here referring to New Zealand or New Zealand poets; it is an essay on “the prophetic accent of our late contemporary English poets” (p. 14). Yet the sentiment seems apposite to what was undertaken in what is termed the ‘South Island Myth’.

[2] Basil Dowling, Canterbury and Other Poems (Christchurch: Caxton Press, 1949), 10–11.

[3] T. H. Scott, ‘South Island Journal’, Landfall 16 (1950): 289–301.

[4] Also known as the ‘anti-myth’, it is a constant theme in the discussions of cultural nationalism. For two contrasting histories see Lawrence Jones, Picking Up the Traces (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2003), and Francis Pound, The Invention of New Zealand (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2009). For a re-stating of the meaning of the South Island myth as a form of regional poetics see Richard Reeve, ‘The South Island Myth: Observations on the Poetics of Mystery in Three Local Poets’.

[5] John Newton, ‘Colonialism Above the Snowline: Baughan, Ruskin and the South Island Myth’, Journal of Commonwealth Literature 34 (2) (1999): 85–96.

[6] John Lehmann, The Whispering Gallery: Autobiography I (London: Longmans, Green, 1955), 263.

[7] Charles Brasch, ‘Notes’, in Charles Brasch ed., Landfall Country (Christchurch: Caxton Press, 1962), 434.

[8] Keith Sinclair, A History of New Zealand (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1959), 301.

[9] A. R. D. Fairburn to Charles Brasch, 27 October 1946, in Lauris Edmond (ed.), The Letters of A. R. D. Fairburn (Auckland: Oxford University Press, 1981), 148.

[10] A. R. D. Fairburn, ‘Some Aspects of N.Z. Art and Letters’, Art in New Zealand 24 (1934): 213.

[11] Fairburn, ‘Some Aspects of N.Z. Art and Letters’, 216.

[12] Charles Brasch, ‘New Zealand, Man and Nature’, Geographical Magazine 12 (5) (1941): 343.

[13] Brasch traces this sense back to mustering at Minaret Station, Wanaka 1927. See Charles Brasch, Indirections (Wellington: Oxford University Press, 1980), 125.

[14] Brasch, Indirections, 178.

[15] Brasch, ‘New Zealand, Man and Nature’, 337.

[16] Charles Brasch, ‘Notes’ Landfall 15 (1950): 186.

[17] Brasch, ‘Notes’ (1950), 187.

[18] James Der Derian, ‘Introduction’, in James Der Derian (ed.), The Virilio Reader (Oxford: Blackwell, 1998), 6.

[19] M. H. Holcroft, The Way of a Writer (Whatamongo Bay: Cape Catley, 1984), 126.

[20] Holcroft, The Way of a Writer, 126.

[21] M. H. Holcroft, Discovered Isles (Christchurch: Caxton Press, 1950), 14.

[22] Holcroft, Discovered Isles, 21.

[23] See especially Holcroft, Discovered Isles, 26.

[24] Holcroft, Discovered Isles, 46.

[25] Holcroft, Discovered Isles, 127.

[26] Holcroft, Discovered Isles, 166–171.

[27] Holcroft, Discovered Isles, 177.

[28] Allen Curnow, ‘To M. H. Holcroft’, At Dead Low Water & Sonnets (Christchurch: Caxton Press, 1949), 29.

[29] James K. Baxter, ‘Recent Trends in New Zealand Poetry’, in Frank McKay (ed.), James K. Baxter as Critic (Auckland: Heinemann, 1978), 11.

[30] Mark Williams, quoted in Stuart Murray, ‘Writing an Island’s Story: The 1930s Poetry of Allen Curnow’, Journal of Commonwealth Literature 30 (2) (1995), 25–44.

[31] James K. Baxter, ‘Aspects of Poetry in New Zealand’, in McKay (ed.), James K. Baxter as Critic, 79.

[32] Peter Simpson, ‘“The Trick of Standing Upright”: Allen Curnow and James K. Baxter’, World Literature Written in English 26 (1986), 373.

[33] Allen Curnow to Joseph Heenan, 7 May 1945, quoted in Stuart Murray, Never a Soul at Home (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 1998), 243, 277 (fn. 56).

[34] Allen Curnow, ‘A Dialogue with Ngaio Marsh’, in Simpson (ed.), Look Back Harder, 77.

[35] Curnow, ‘A Dialogue with Ngaio Marsh’, 77.