Being In The Room: Charles Anderson

In the final instalment of our weeklong series on the New Wave of young Kiwi non-fiction writers, Gavin Bertram talks to former Junior Reporter of the year Charles Anderson about multimedia storytelling, opening scenes and not being the hard-nosed scoop reporter.

Over the last few years, our print media landscape has benefitted from the emergence of a new group of talented young feature writers. This week, Gavin Bertram sits down with five of them.

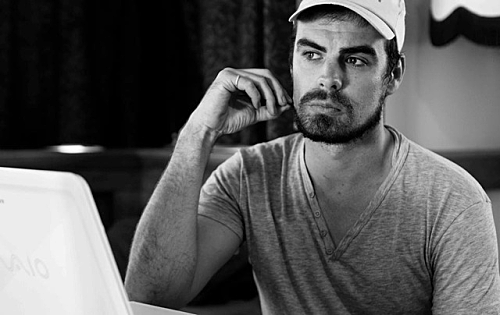

Now at The Press, Charles Anderson began his journalism career at the Nelson Mail, before freelancing while travelling overseas and a stint at the Sunday Star Times. His previous Canon Media Awards honours are winning the Newspaper Reporter of the Year – Junior in 2011, and being a finalist in Newspaper Feature of Writer of the Year – Senior in 2012, and Newspaper Feature Writer of the Year – Junior in 2010 and 2011. In 2014 he is a finalist in the both the Newspaper Feature Writer General and Newspaper Feature Writer Arts and Entertainment categories. He's also a budding photojournalist - this story's feature image was taken during a trip to India in 2011.

What was it that first drew you to journalism?

When I was 15 my aunt gave me a book by John Simpson, a war correspondent, and it detailed all his travels and meetings with dictators and leaders around the world. The idea was to inspire me, and it kind of did, so from there I had in mind that I wanted to get into that line of work. I enjoyed writing and was reasonably good at it. And I enjoyed the idea of having an excuse to go to places that were interesting and out of the ordinary. It led me down that path, but I didn’t seriously look to get into it until I was at university.

Loosely, what has your career path been?

I think it was the second year that Fairfax did their internship programme, and I went to the Nelson Mail out of Canterbury Journalism School. That was where I kind of got seriously into experimenting with writing because once you’ve proved you can write your average news story, generally you have a bit of leeway to try things out, because there aren’t many options in a small newsroom in terms of offering something different to the paper.

In that time I also got to go to Indonesia for a couple of months, and after that I went overseas for a year, just freelancing and travelling around, and went to the Cricket World Cup in India and covered that. I came back and started at the Sunday Star Times, doing general news but with a bent towards doing the longer stuff. And then I came down to The Press.

What is it about feature writing that particular appeals to you?

I’m unapologetic about not being the hard-nosed scoop writer. I enjoy following a story and getting into it, but what has always appealed to me is the idea of a story and how one approaches it in an interesting and novel way that people are going to want to read to the end. Obviously news writing has its place, but it’s the longer stuff, and the idea of how one grabs a reader and plays with them a bit in terms of holding out the ending, that’s always interested me. Looking for smaller details where someone might go ‘that’s not a big deal’, but you might have worked hard as a reporter to report that small detail that you think is particularly telling. Putting those together in a creative way and having the space to explore themes and ideas and also the story itself, that’s the stuff I’ve always loved reading, and it’s the stuff that’s inspired me.

How have you developed the specific skills that long form writing requires?

I’d say most of it was off my own bat. At journalism school we got introduced to the idea of features, but it was more the idea of colour writing. I don’t really like ‘colour writing’ because it makes it sound like good writing is superfluous to a reporting process. A lot of it was reading inevitably American stuff, which is quite a unique way to approaching narrative journalism over there, as opposed to Britain or Australia which is what we model most of our feature writing on here. They’re a bit more experimental and a bit more purist about their idea of a narrative story.

So it was just reading a lot of stuff that I admired and trying to slowly use elements of those stories into my own work. When I was in Nelson I wrote a feature about the local men’s shelter, and I had read Gay Talese’s story on Joe DiMaggio, where he kind of uses himself as a third person character, calling himself ‘the man from New York’. I thought that was interesting and was a stage where I wanted to try some stuff, so I put myself a third person character. With Fairfax features the style is always “he says”, in the present tense rather than in the past tense. So it came back from the editing stage and the whole thing had been changed from “said” to “says”. So learning by experimenting with stuff and figuring out what works and what doesn’t.

Is there a tension between the news and features departments at newspapers in New Zealand?

I think there probably always is, because features are broadly seen as a bit of a luxury. Features have been shrinking over the last while, and I guess for a news writer they might see a feature writer working on one or two pieces every two weeks when they’re grinding stuff out. But I’ve always been in the news team and I write features on the side, partly because that’s the just the way my jobs have developed, and I think as a news reporter if you’re going to really immerse yourself in a feature then you have to really care about it, and you’re not churning one out every week. You really want to spend some time on it and invest some energy and effort into it.

What are the subjects that you most enjoy writing about?

I’m pretty broad, but there is a weird thing that’s popped into my work over the last couple of years that are basically elements of mystery stories and adventure stories and things that are missing. The first one was about a missing ship that may or may not have carried gold down in the sub-Antarctic islands.

But I think everyone’s looked at a story and thought ‘that’s definitely a great story’ and when they’ve gone down that path they’ve realised it’s not that great but they have to write it anyway. You might get a bit too excited before you even start the reporting process. Hopefully by trial and error you learn to be cautious about getting too excited.

What is the first step once you’ve grabbed hold of a subject?

I need an opening scene to know where I’m going. Even if I haven’t got the guts of the story I need to know in my mind that if I start on this aspect of the story then it will give me a good opening or a good lead first. But you don’t want to be too strict about that because you might be surprised along the way and realise your opening doesn’t actually match at all. It’s a bookmark to start the process, an opening line which sums up the mood or an idea that you will carry the whole way through.

How do you decide how broadly to interview?

It can be difficult. I’m working on a story at the moment that I’m very new to, and it’s very much a trawling expedition to try and find out as much as you can about stuff. It can sometimes be a little overwhelming because you don’t have a clear direction on where you’re going, you just know you have to try and interview people. With other subjects there are obvious characters and people involved who you need to interview.

You need an in-your-face sort of personal aspect to it, the human element that people are going to be interested in regardless of whether they’re interested in the subject. You’ve got to think of things in a storytelling way without being too simplistic, and know the protagonist and the antagonist, and then you’ve always got the talking head people with expertise, who are interesting, but don’t necessarily drive the story forward.

Are the people you approach generally receptive?

The way I would approach them for a feature interview is very different to how I would for a news interview. You ideally have a bit of time and space to go and meet someone and put them at ease. You’re not straight in there and taking down notes. You can get to know someone which is generally easier than calling them on the phone and saying ‘here are 10 questions’.

Ideally I won’t be using direct quotes said to me, you want to be put in a situation where the subject feels comfortable and they’re talking naturally, ideally with someone else who is relevant to the story. It illuminates more about a story or situation if someone is talking in their own comfort zone.

Most people haven’t had any experience of journalists. Interviews fill in the gaps, but the idea is to limit those face to face interviews and let them blend in with a more natural situation. They’re not mutually exclusive, and often people are going to give you more interesting answers or tell you stories they wouldn’t otherwise have told you if they’re relaxed and just going about their daily business without being pressured or feeling intimidated.

How do you know when you have enough information?

When you can sort of see the story in your head and you can see the elements coming together and there are no burning questions left to ask. If you can see that structure in your mind and one more person might just be more detail that isn’t really relevant to a good story.

You can report and report, but a good idea is to keep your story as tight as possible. You’re not there to be an encyclopaedia of the subject, you’re there to tell a story that illuminates or explains a certain subject or person or whatever. You’ve got to keep in your mind that you’re not there to tell everything: you’re just there to tell a good, interesting, and readable story.

What’s your process for ordering the information you’ve gathered before you start writing?

You can have screeds of interview notes, and like news writing you’re looking for key things that aren’t going to repeat a point you’ve already made. You want things that will move a story along a path. Sometimes in an interview people will repeat themselves, and you have to be quite ruthless about what is needed and what isn’t.

The benefit of doing a long interview is that occasionally it can lead to very good information or details that wouldn’t occur in a shorter interview. The benefit of the long reporting process is the sort of gems that pop up, and everything else around the gems is sort of superfluous, and leading to towards the gem.

Is the writing the most enjoyable part of the process?

It depends. The reporting is more fun, especially when it’s an interesting story and you’re getting out and going somewhere interesting, meeting someone interesting. The writing can be really good when you know where you’re going with it. Occasionally you know exactly where you’re going and it’s smoothish sailing.

The difficult part if you’re dealing with a long piece is going through your notes and thinking ‘that’s kind of interesting’ and jumping back and forth between your notes and your screen. It’s very choppy and change-y sometimes just figuring out what the hell you’re going to write about, and then the actual process of writing. If it’s smooth then it’s great, but if you get into a situation where you don’t know where you’re going then it can be quite annoying and soul destroying. Ideally you can walk away and give it a day or so and come back to it.

How many drafts can you go through?

Not that many. It depends who’s editing the work, because that’s a big part of whether you think a draft is needed or not. I think the most drafts I’ve gone through would be about up to 10, which was the longest piece I’ve written and a different kettle of fish. So, generally two or three.

My experience of how editing works in this country is that we don’t place that much importance on the relationship between the writer and the editor. That kind of dialogue doesn’t really happen that much, so over the years I’ve opened up unofficial dialogues with people whose writing I like and who I respect. It can feel like a vacuum if you’re just writing; you might think it’s the greatest thing in the world but when someone else reads it they might not know what you’re talking about because you’ve been a bit too out there.

Your story about the ongoing effort to find the plane Aotearoa 85 years after it disappeared was the first real multimedia storytelling project in New Zealand. How did that develop?

When the New York Times did Snowfall in 2012 there seemed to be a quite a few of those kinds of nicely designed, full screen stories that looked really great and seemed to usher in a new idea of how to integrate multimedia elements with good writing in a long format. This new twist on it seemed to point towards a magazine idea in terms of a nice layout but obviously you can have more elements to it on your computer, and I thought I’d give it a shot.

I had been following that story for a while, just keeping tabs on it, and it had elements of things I was interested in. I like stories that have an historical aspect, partly because I like history, but also because there is usually a large amount of material in archives that can be really nice to use. That kind of element brought into the present, and this is the epitome of that, where you have people going out and bushwhacking looking for an 85-year-old plane wreck.

It had good potential for having multi-media elements to it, maps and video, and photographs – a lot of elements I thought could work really well on top of the archive stuff. I pitched it to the Star Times as a big project and got Mike Scott, who I think is one of the best video journalists in the country, on board with it. He came down for a weekend and we did that aspect of the reporting.

At that stage I’d already done a lot of the background stuff, so we had a body of things to take to Fairfax head office in Wellington, and I took them through what we had, and showed them examples of what media organisations had done. They were quite excited because they had seen a similar trend and wanted a story with which to do it. You obviously need someone to push it. It had this kind of long build up and I hope some time in the future I’ll be able to write an epilogue when they solve the mystery.

These sorts of projects bring attention to a media organisation, so hopefully people go ‘that’s pretty cool’ and go back to that site. I guess it’s seen as a loss-leader in that respect. But also you see more and more aspects of potential money-making coming into it as well, advertising sponsorship starting to creep in with the New York Times. I think what we did was more a ‘look what we can do’ and throw some resources at something and create something cool. That doesn’t necessarily have to be the future. Hopefully because of people wanting to read well presented, interesting stuff, there will be interest from sponsors and that sort of stuff.

When I was working on it, this guy Tom Shroder, who'd edited Gene Weingarten - a Washington Post writer who’d won two Pulitzers - I saw he’d been made redundant and was a gun for hire editing whatever. I thought it would be great to have someone of that calibre edit your work. He said sure. I did it out of my own pocket, but you get to a stage where if you want to be better at something then you want someone to be pretty critical and somebody who’s got experience like that is pretty invaluable.

That was a really interesting editing process, because I had about 6000 words in the final draft to him, and we had about eight back-and-forths and he would just go through the whole thing and have screeds of notes and questions. Everything had to be explained and qualified and it made me realise that the reader isn’t stupid, but they do need to be led along a path and everything has to be easy to understand. It’s a lot easier to read if it’s just effortless because everything makes perfect sense in their minds.

The final draft was 8000 words, so editing wasn’t necessarily cutting down; it was making it more intelligible and readable.

It was nice when it came out, because you want to promote it, and being able to say he edited it gave it some credence in the States. It wasn’t just some hack at the bottom of the world.

Being In The Room continues throughout the week.

Charles's compiled writing can be found here, and he tweets at @cdlanderson.

Previously featured in this series:

Duncan Greive

Naomi Arnold

Ben Stanley

Beck Eleven