Before Words Get in Between

Kirsty Baker on the subtle modes of resistance and subversion in The Dowse's concurrent exhibitions, Embodied Knowledge and Can Tame Anything.

Kirsty Baker on the subtle modes of resistance and subversion in The Dowse's concurrent exhibitions, Embodied Knowledge and Can Tame Anything.

The 1980s in Aotearoa marked the advent of one of the most aggressive experiments in structural economic adjustment to be implemented in the developed world. Market expansion and privatisation replaced the welfare state model, championing competitive individualism over collective social responsibility. Big business may have reaped the financial rewards, but the free market came at a price. It is a price that many of us continue to pay. Stagnant, often unliveable wages, perilously temporary employment, the volunteer labour economy, massive student debt, an upsurge in child poverty: all have been drastically exacerbated by neoliberalism. In this 2016 piece for The Guardian, George Monbiot points to the fact that “so pervasive has neoliberalism become that we seldom even recognise it as an ideology.” Rather than an inevitable state of being, the social, material and cultural conditions in which we find ourselves are produced by the systems of power which govern society.

If you can in fact tame anything, what is being tamed here and – more importantly – why?

Embodied Knowledge and Can Tame Anything, showing concurrently at the Dowse Art Museum, present works made by women during this prolonged period of economic, cultural and social change. Embodied Knowledge “draws on the histories of feminism, critical theory and installation art practice in Aotearoa New Zealand.”[i] The exhibition consists of large-scale sculptural and installation works made predominantly in the 1980s, by Christine Hellyar, Maureen Lander, Vivian Lynn, Pauline Rhodes and The Estate of L. Budd. Can Tame Anything, focusing on the present moment, brings together the work of Ruth Buchanan, Alicia Frankovich, Mata Aho Collective and Sriwhana Spong. While each exhibition stands alone, they have been situated alongside each other in a way that draws out their overlapping thematic concerns.

When artworks are brought into close physical proximity, surprising conversations can sometimes result. As I thought through these two shows, I began to trace the thread of a conversation that became increasingly insistent. If you can in fact tame anything, what is being tamed here and – more importantly – why? Many of the works exhibited in Embodied Knowledge and Can Tame Anything subtly explore the ways that artistic practices can interrogate and subvert the systems of power which shape our everyday lives. By the early 1980s the arts infrastructure of Aotearoa was relatively well established. A national history of art had been written which placed the male Pākehā painter at the heart of its canon. A network of national and regional museums, public and dealer galleries had spread across the country. The ideology shaping this network came under increasing scrutiny in the 1980s by those excluded from its apparently ‘neutral’ spaces. The growth of both feminism and Māori activism during this period led to critiques of an arts landscape that was considered both Eurocentric and patriarchal. This art-market value system, which privileged the commodifiable art object, was also challenged by artists who turned to installation, site-specificity and temporality in order to evade easy categorisation.

The desire to collect, to name and to order is deeply tied to the project of colonisation; museum cabinets around the world are still filled with items violently removed from their cultural contexts and reconfigured as objects of wonder

Notions of museological categorisation are explored by Christine Hellyar in her mixed-media sculptural installation Thought Cupboard: Enhancing (1983). A glass-fronted wooden cupboard sits against the gallery wall, filled with hats and head-shaped forms made from a variety of natural and man-made materials. Resembling museum display cabinets, their contents organised and classified by type, the tactility of the objects within invite our touch. We are, of course, denied such a pleasure. The protective glass cabinet serves to isolate its contents from the viewer, the museum rendering them objects for contemplation rather than experiential encounter. The desire to collect, to name and to order is deeply tied to the project of colonisation; museum cabinets around the world are still filled with items violently removed from their cultural contexts and reconfigured as objects of wonder. The title of Hellyar’s work implies that there is an underlying ideological component to the classifying and display systems of museums. That those same systems by which objects can be ordered and categorised can also be turned on our systems of thought: that we too can be tamed.

Drawing attention to the manner in which the built environment of the gallery acts upon us, the work of Ruth Buchanan often forces subtle alterations in our physical interaction with space. Her 2018 work Break, break, break. Broke interrupts the visitor’s progression through the gallery space. Chain-link curtains hang in the entrance – or exit – of each exhibition, demarcating a constructed threshold that is both physical and curatorial. Distinctively bright pink, their lowest fringes a golden yellow, like the contents of Hellyar’s Thought Cupboard they invite the touch. During one of my visits I watched as a toddler gleefully accepted the invitation, running repeatedly through the aluminium chains, thrilled by their rattle and sway. It took very little time for a parent to swiftly arrive and pull him away. We are conditioned to adhere to a system of appropriate behaviour, to obey the unwritten rules of the gallery or museum. Buchanan’s interventions serve to make clear the constructed nature of such systems.

Where Hellyar and Buchanan draw our attention to the systems of power that shape our behaviour within the gallery space, the large-scale fibre work Tauira (2018) created in situ for Can Tame Anything points insistently outward. The work was made collaboratively by Mata Aho Collective, a group of four Māori women: Erena Baker (Te Atiawa ki Whakarongotai, Ngāti Toa Rangātira), Sarah Hudson (Ngāti Awa, Ngāi Tūhoe), Bridget Reweti (Nhāti Ranginui, Ngāi Te Rangi) and Terri Te Tau (Rangitāne ki Wairarapa). In an email conversation with Mata Aho, they collectively explained:

We initially conceived Tauira as a sister work to Te Whare Pora, which was our first piece created for the Enjoy Summer Residency in 2012/2013. That work is made from black faux mink blankets that really suck in all of the light. Visually, it’s a big black presence and creating an installation that looks opposite to that was something that we’d been thinking about for a long time. So we started researching and theorising about Te Ao Marama, the world of light.[ii]

Over time the work takes on a quiet defiance in its refusal to adhere to the confines of the gallery space. Created out of synthetic marine rope, the white form spans a long stretch of the gallery floor. Displayed in a self-contained space, the gradual sloping length of Tauira reaches up from the ground and out through a horizontal window punched through an internal gallery wall. The bright shaft of light the window exposes seems to exert an inexorable pull on the work, drawing its rhythmic form upwards until it breaks free from the confines of the space. The enclosed area into which it stretches cannot be entered. It can, however, be glimpsed through the window. Flanked by ceiling-height windows on two sides, the rope stretches, unwoven, through the bright air before cascading down to rest at the base of one of these external windows. The tight weave of the manufactured rope ends has been painstakingly unpicked by hand to reveal the gleaming individual fibres from which it has been constituted. Glimpsed from inside the gallery, the ropes are framed by a profusion of bare tree branches. The same windows which allow us to see out, also allow those outside of the gallery space to look in. Mata Aho have positioned the work in a way that allows for continual visual access, entrance to the gallery is not a necessary requisite for a partial viewing of Tauira. This accessibility is a key concern for Mata Aho:

As a rule, we like to address accessibility in our work through our use of material. In using ubiquitous materials that can be found both domestically and industrially, we hope that the recognisability can act as an initial ‘in’ to the work. The window gallery space extends our idea of accessibility even further, as you mentioned, viewers don’t even have to go into the gallery to be exposed to Tauira. When we were installing the work, we spent quite a bit of time in that window gallery. It was a great chance to witness the variety of people walking by, from parking wardens to high-school students.[iii]

Language is not simply a benign communicative tool, it mediates our experience of the world

The material journey Tauira makes towards the light can be seen as the physical manifestation of the exploration of Te Ao Marama undertaken by Mata Aho. Such exploration is often tied to language, and the power it both holds and encodes. In Aotearoa the systems of power embedded in language have had a deeply contentious history. In an essay titled Translation and The Treaty Maarire Goodall (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Māmoe) wrote about the material and emotional damage done by language in relation to Te Tiriti o Waitangi:

There was serious mistranslation here, which caused much conflict. The most important problem with mistranslation of Article Two is that many Maori believed, and still do, that they were not ‘subjects’ of the Crown, Britons were, and that Maori ‘sovereignty’ (for which in fact ‘Tino Rangatiratanga’ would be the best translation) was preserved, while the Kawanatanga was merely authority for the Crown to control its own immigrant subjects in New Zealand.[iv]

Language is not simply a benign communicative tool, it mediates our experience of the world. The choice of Tauira as the title for this work demonstrates both a resistance to the primacy of the English language in Aotearoa, and a demonstration of the rich complexity of te reo Māori. The wall text includes four translations of the word Tauira – student, teacher, pattern and sampler – and also mentions the fact that tāuira translates to ‘gleaming.’ Each of these layers of meaning can be discerned within the work. Looking up the word tauira prior to this exhibition opening I found 18 translations. Having recently started learning te reo Māori, I am continually overwhelmed by its vertiginous richness and fluidity, particularly in comparison to the rigidity of English. The weaving of so many of these meanings into Tauira reminds me of an essay by Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, in which she speaks of the connection between language skills and karanga – like weaving, a female practice:

At this time, many older women – kai karanga – are concerned with training successors, although in their own youth they learned by merely listening, by being present. Otherwise the improvizational elements – the poetic genius and spontaneity – would sink beneath rote-learned, hard-edged structures. Competence in Maori language is essential for karanga, for the poetry to live on.[v]

Though we are shown these actions, we are denied their tactility: the rasping friction of her hand against soft, pitted stone, the tender caress of her fingers upon ornately painted iron fencing

Tauira is not the only work across these exhibitions to engage in the politics of language. Sriwhana Spong’s 2016 video work This Creature takes the enigmatic figure of English Christian mystic Margery Kempe as its starting point. Filmed on an iPhone, This Creature visually traces a walk taken by Spong through London’s Hyde Park. Denied the sight of her body, we see only her hand. We watch as she trails it under the water flowing from a fountain decorated with carved swans and as she holds her palm open to feed the small birds that flit sporadically in and out of the frame. Though we are shown these actions, we are denied their tactility: the rasping friction of her hand against soft, pitted stone, the tender caress of her fingers upon ornately painted iron fencing. Vision is inadequate in conveying the sensuous physicality of touch. This is echoed in the work’s narrated soundtrack, which interrogates the constraints of language on experience, through an exploration of Kempe’s autobiography. Medicalised language is framed here as a masculine system of power, harnessed to label and pathologise Kempe’s unruly emotions. “Historians have named her neurotic, abnormal, suffering from post-partum depression, psychosis, frontal lobe epilepsy, Tourettes, menopause. But she called it a gift.” Kempe’s gift manifests itself in various forms. She has visions, hears voices and succumbs to fits of weeping. Early on in the piece, Spong narrates a personal tale, explaining an urge she sometimes feels to lick inanimate objects. She speaks of her inability to find a precise linguistic definition to characterise this desire, of the limits of language to allow her to rationalise this embodied urge. The doctor, she explains, sees it as a desire to return to the point in childhood where objects are explored by putting them in the mouth: “that period before the tongue can speak, before words get in between…” This Creature relies upon the visual and the linguistic, while continually pointing to the inadequacy of each of these systems of meaning to capture haptic and emotional experience. Language as a system of power is continually evaded and resisted as we circle back again and again to that period “before words get in between.”

The voices in Kempe’s story act as collaborators, their multi-vocality enriching her narrative, she is ‘a woman of many voices.’ A collaborative working practice has frequently been used by artists to disrupt the power dynamic of the art world, shaped as it is by the mythic figure of the individual male genius. Numerous collective models of working are in evidence in Embodied Knowledge and Can Tame Anything. Working within a model of collective anonymity, the works displayed from the Estate of L. Budd offer an entangled network of linguistic systems and structures which we often take to be objective and neutral. Ruth Buchanan’s practice insinuates itself into the gallery space, her interventions working in collaboration with other artists’ work. Spong’s This Creature, for example, is mounted within the green latticed framework of Buchanan’s 2016/2018 work Circumference. For an insightful consideration of the intersection between language and collaboration in Buchanan’s work, this eloquent essay by Simon Gennard is worth revisiting.

We hope that being four Māori women, taking up a lot of space physically in art spaces will inspire other Māori women, other women in general, to get in there and take up space too

For Mata Aho Collective, their collaborative approach to art-making is deeply tied to their cultural identity:

We do see collective-life as fundamentally Māori. It is something that we sometimes have to defend, particularly when institutions are used to working with individuals…Along with collectivity also comes an increased notion of visibility. We hope that being four Māori women, taking up a lot of space physically in art spaces will inspire other Māori women, other women in general, to get in there and take up space too.[vi]

Their collective approach is extended through their relationship with tuakana Maureen Lander. Lander’s working practice carries the weight and power of a wide and diverse genealogy, drawn from Māori and European forms, practices and understandings. Recently, she sent me a list of her early projects, spanning a period from 1986 to 2000. Of the 26 listed, it is telling that 12 were made in collaboration with others, from children to professional artists. She talks of the development of this mode of practice in relation to her first installation, made in 1986:

Karanga, Karanga at the Fisher Gallery in Auckland was the first public exhibition I had participated in and my installation was a seminal piece in that it (literally) contained the seeds for much of my future art-making, including a practice of working collaboratively across the arts with writers, poets, composers, weavers and other artists. In the lead up to the exhibition I invited a small group of the other Karanga, Karanga participants to join me in gathering flax seeds from the hills above Piha beach.[vii]

Lander speaks here not only of the importance of human collaboration, but also the value of processes which occur outside of the gallery or studio space. The act of collecting flax seeds is more than a simple gathering of materials, it is an act of guardianship and care for natural resources such as harakeke and muka which she uses frequently in her work. This guardianship of resources also broadens the concept of collectivity, extending its reach into the past and future simultaneously.

Lander’s innovative use of these traditional materials is evident in the four works on display in Embodied Knowledge. Installed together in a deep recessed alcove, Ngā Roimata o Ranginui (2015), Iorangi I (2012), Iorangi II (2012) and Wai o te Marama (2004) are suspended from the ceiling of the dimly lit space, each individually illuminated, casting intricate shadows upon the floor and walls that contain them. As the wall text states, “they all take the form of suspended maro (aprons) or rapaki (skirts).” These are not, however, examples of traditional Māori weaving. By translating forms and materials into her work that are freighted with cultural meaning, Lander refutes the easy categorisation of ‘sculpture’ according to European artistic conventions. Walking around and peering through these suspended works I see evidence of a wealth of diverse cultural knowledge and experience. For all of its visual difference to the work of Lander, I can’t help but think immediately of this untitled Eva Hesse work, similarly suspended, tactile and evocative. However, much of the richness evident in these works is inaccessible to me, a recent Scottish immigrant to Aotearoa. Lander shows me the weight of knowledge that is held in the forms of maro and rapaki, in the feel of harakeke and muka, and in the poetry of their te reo titles. Their delicate forms refuse to be pinned down within specific cultural or artistic categories. Evading the defining power of the museum, they complicate the urge to categorise and label according to cultural conventions.

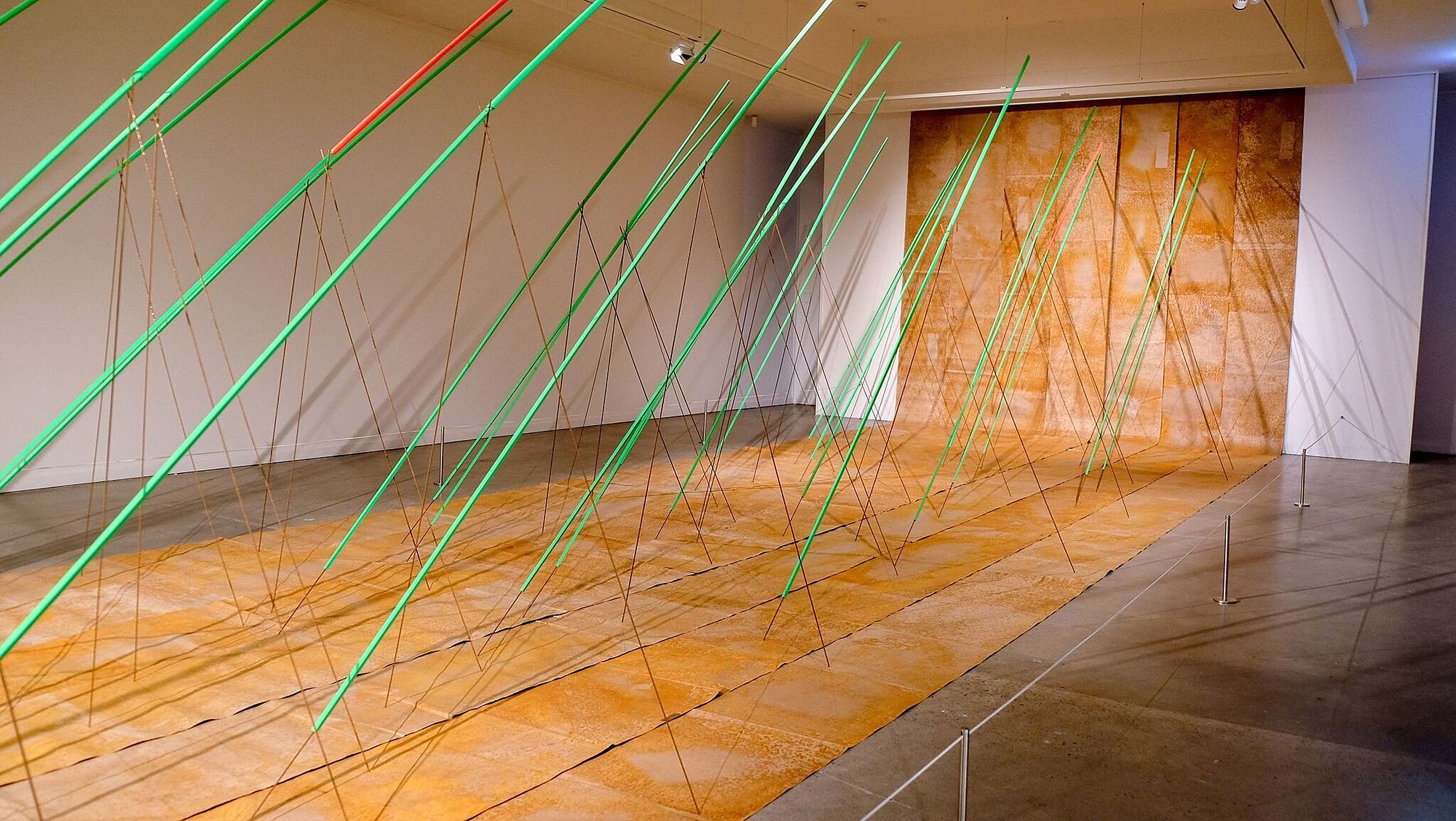

Pauline Rhodes’ work also exists outside the confines of easy artistic definition. Her long and open-ended artistic practice is concerned with an interrogation of natural and built space, and the ways that we exist within these spaces. Much of her work is site-specific, made in the landscape of Aotearoa: bright red circles laid on the wet intertidal sand of Otago, yellow teardrop-shaped loops snaking across the tussock of the Port Hills, and incongruously fluorescent green rods marking the view on Banks Peninsula. First made for the CSA Gallery in Christchurch, Rhodes has reconfigured her 1983 work Extensum/Extensor for display at the Dowse. Though made specifically for display in a gallery environment, the work also occupies the charge of external space. As Rhodes said of the 1983 creation of this work: “In the immediately preceding project the ‘EXTENSIONS’ were taken into the LANDSCAPE and MOVED from one SITUATION to ANOTHER, ARTICULATING and EXPLORING wide OPEN SPACE and panoramic vistas. This forms part of a continuing involvement with open and enclosed situations, indoors and outdoors.”[viii] So large that it threatens to overwhelm the room, it immediately makes you aware of the space that you occupy in relation to it. Rolls of rusted paper spill down the gallery wall and stretch out across the floor, leaving a narrow border around which visitors walk to view the work. While we can pass easily around Lander’s work, Extensum/Extensor is inaccessible to us, bounded by an unobtrusive barrier. This denial of access makes us hyper-aware of our bodily presence in the space. Her work, charged with such spatial energy, almost demands physical engagement. Looking closer, it becomes evident that such engagement would be inevitably damaging. Though the sloping green rods are held up by metal supports, their legs are perilously entwined, balanced precariously by the precise lean of their weight. To enter would be catastrophic. Vivian Lynn’s large-scale 1983 installation, Lamella Lamina, on the other hand, is best experienced from within. On the opening night of Embodied Knowledge, I was lucky enough to walk within the space the work occupies. Passing between columns constructed from layers of tracing paper, indecipherably dense with meaning, I became cautious in my movements. Navigating these tall forms, stepping upon the long slices of shadow they cast upon the ground, I was forced to consider my own bodily relation to the space I occupy and the systems of behaviour that I am conditioned to adhere to. Upon revisiting the exhibition I was unsurprised to find that the work had been fenced off. It is not unusual for galleries to put such protective measures in place several days after an exhibition opens. The threat posed to Lynn’s fragile sculptural grove by the human body makes this a sensible decision. However, I couldn’t help but feel a little melancholy in the face of such a clear boundary of physical exclusion.

It would be easy to simply step over the low fence. The fact that such an unobtrusive obstacle is an effective way to keep visitors out of the space makes clear our obedience to the systems of signification that shape our journey through the world. The women whose work is on show in Embodied Knowledge and Can Tame Anything offer alternative ways of navigating that journey. They show us the power of alternative ways of seeing, of speaking, of thinking, of feeling; they open out the possibilities of how we can navigate the world without blind adherence and acquiescence to limiting systems of power. They quietly, but insistently, urge us to resist taming.

[i] Wall text for Embodied Knowledge at The Dowse Art Museum.

[ii] Mata Aho Collective, email communication with the author, 2018.

[iii] Mata Aho Collective, email communication with the author, 2018.

[iv] Maarire Goodall, “Translation and The Treaty,” in Now, See, Hear! Art, language and translation, ed. Ian Wedde and Gregory Burke (Wellington: Victoria University Press for the Wellington City Art Gallery, 1990), 29.

[v] Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, “Karanga Te Ao, Karanga Te Po,” in Mana Wahine Maori: Selected Writings on Maori Women’s Art, Culture and Politics (Auckland: New Women’s Press, 1991), 111.

[vi] Mata Aho Collective, email communication with author, 2018.

[vii] Maureen Lander, email communication with the author, 2018.

[viii] Pauline Rhodes, quoted in Christina Barton, Ground/Work: The Art of Pauline Rhodes (Wellington: Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi, 2002), 114.

Embodied Knowledge

7 July – 28 October 2018

&

Can Tame Anything

4 August – 25 November 2018

The Dowse Art Museum

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with The Dowse Art Museum, which covers the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.