The Persistence of Ruth Buchanan: A Discussion of 'Bad Visual Systems'

Simon Gennard looks at 'Bad Visual Systems', an Adam Gallery exhibition organised by Berlin-based artist Ruth Buchanan and featuring work by Judith Hopf, Marianne Wex, and Buchanan herself.

Simon Gennard looks at Bad Visual Systems, an exhibition organised by Berlin-based artist Ruth Buchanan and featuring work by Judith Hopf, Marianne Wex, and Buchanan herself.

Ruth Buchanan’s work takes place between the lodging of an address and the inevitable response – that is, between someone calling out a name, a pronoun, or some other identifying feature, and someone else recognising that they are being spoken to. The two people in this scene could be an artist and a viewer, an artist and another artist, an artist and an object of inquiry. Buchanan’s work protracts the moment of address, and in doing so examines the ways in which we are constituted by language. We get made, and remade, in language. The addresses to which we respond, even unwillingly, are what make us subjects. Buchanan’s work is not interested in offering a way out of language; rather, it teases out whatever contradictions, ambivalence, or messiness go into both the call, its response, and those rare moments where something gets caught as it makes its way from one body to another.

Or maybe this is an inefficient way of saying that entering Bad Visual Systems – on display at Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi until 22 December – is a little like walking in on a conversation you may or may not have been invited to. The exhibition is dense with calls heard and unheard. In it, Buchanan has set her own work in conversation with that of two other artists, spanning different decades and continents. The work of Buchanan, Judith Hopf, and Marianne Wex is arranged throughout the three floors of the gallery. At times, the conversation elicited between works and artists is one of proximity. In the front window, for instance, one of Hopf’s angular concrete snakes (with teeth and tongues made from printed emails) navigates its way between two small rugs by Buchanan.

Elsewhere, this proximity gets mixed up. It becomes almost impossible to determine where one work ends and another begins. In the middle of the gallery on the top floor, a gallery host sits and waits upon a purple couch, upholstered by Buchanan. When visitors pass the couch, the host will hold out an iPad and invite visitors (sometimes desperately, sometimes meekly, depending on who is hosting) to sit and view Hopf’s video More (2015). For four minutes, visitor and host enter an awkward communion as a satellite image zooms in and in and in from space, to a park in Berlin, to a blurry figure standing on a patch of grass, to a strange interior realm in which words dance around each other. The words rearrange themselves from a series signifiers into a constellation of forms, and eventually, as the promise of a stable syntactic relationship slips away, the words themselves wear out; they disappear. After a few seconds of silence, a woman’s voice says, “This emptiness is normal.” And with this declaration, the attachment between host and visitor is severed.

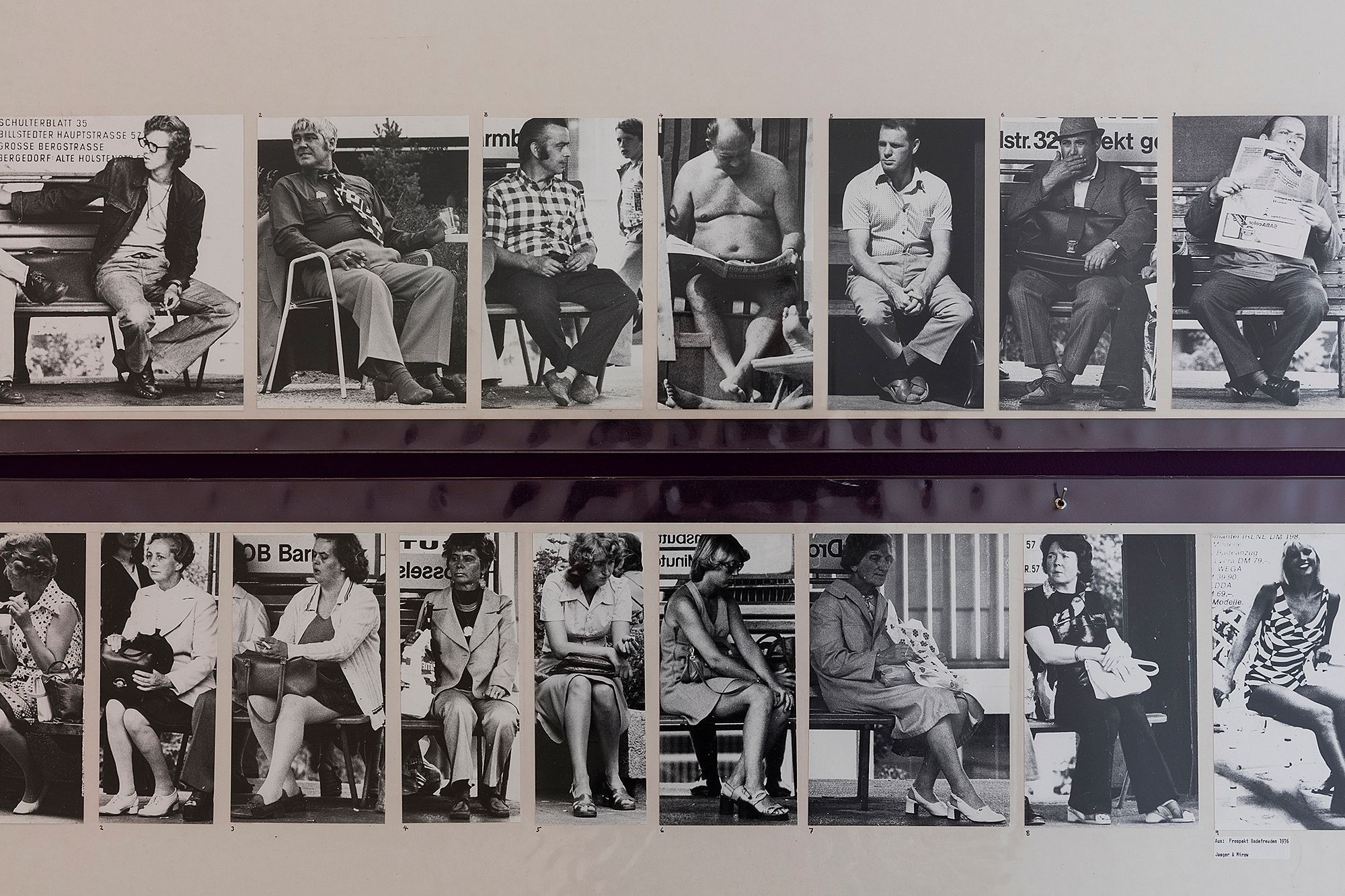

Elsewhere again, Buchanan intervenes in the work of one of her fellow artists, altering a mode of presentation, and thereby manipulating the encounter between artwork and viewer in strange and unpredictable ways. Marianne Wex’s series Let’s Take Back Our Space, first produced as a book in 1979, is an archive of gestures. A selection of thousands of photographs found and taken by Wex, representing the discrepancies in body language, posture, and movement between men and women, is presented in the exhibition in two galleries, across two floors, upon two long rows of purple freestanding boards with turquoise steel framing. The boards cut through the galleries, making the narrow spaces narrower, and forcing an awkwardness into one’s step, as one has to make oneself smaller to avoid brushing strangers, and to avoid the jutting legs of the display system. At the end of each gallery is a mirror. The mirrors double the archive, making it even more abundant than it already is; making Wex’s archive ongoing, unruly, and impossible to completely obtain. These mirrors also elicit scrutiny from the viewer. I found it difficult not to keep glancing at myself as I made my way along the gallery. The arrangement seemed to be an attempt to set up a relation – perhaps even an equivalence – between the bodies in the photographs, and those of visitors to the exhibition.

My friend saw herself in Wex’s work. She noticed, that is, a certain resemblance between herself and the women in the photographs – the ways in which weight is distributed, the ways in which the women fold in on themselves, so as to take up as little space as possible. But she noticed, simultaneously, herself noticing. In the mirror, of course, but also in her own archive of reading and writing, in the kind of critical interventions that have made their way into common parlance since 1979. In noticing, she found herself resisting. Or, to put it differently, in identifying, she found herself disidentifying – with the women, with the scene, with her own representation in the mirror. She found herself, that is, inside a system, aware of its mechanics, but without the means to escape.

I am interested in the afterlives of such political art. How does a genuine commitment sustain itself? How does an earnest address, a will to imagine the world otherwise, keep its faith? How do we stop ourselves from turning away – especially when the language of the work might initially read as anachronistic, or myopic. It might be easy to detect a certain essentialism in Wex’s work. Or to note its overwhelming whiteness. Or its presumption of heterosexuality. An insistence upon a binary leaves little room for attending to whatever ambivalence might emerge in between two poles. But dismissing the work for what it might neglect means disregarding whatever pull it may still have. The conceit of Wex’s work might seem obvious. Courtney Johnston has described it as a kind of predecessor to manspreading. Its ongoing force, then, may have something to do with its abundance, the way the images melt into one another when seen in quick succession, the way they stand as case studies, pieces of evidence, becoming almost unbearable when viewed en masse.

Using a friend to illustrate the ongoing potency of Wex’s work brings up the question of my own capacity to write about this exhibition. And bringing it up, in this text, might be read as attempt to deflate any possible criticism – as if acknowledging the limitations of my perception might make up for whatever inevitably gets left out. I neither identified nor resisted identification with the men arranged in layers above the women. But my own ability to do so is predicated on the fact that – though I do not heed the call of masculinity particularly enthusiastically, and for all my investment in my slight lisp and dainty wrists – being a man means not being subject to the same processes of self-evaluation, of surveillance. It means having a body and not really considering it.

The title of the show (and the epigraph which prefaces Christina Barton’s essay on it) is taken from Donna Haraway’s 1988 essay ‘The Persistence of Vision’.[1] In the essay, Haraway argues for a method of inquiry that insists upon its own partiality. She writes, “Vision is always a question of the power to see – and perhaps of the violence implicit in our visualizing practices. With whose blood were my eyes crafted?” The model of knowledge production argued for by Haraway would always treat knowledge as situated within networks of power, subordination, omission, and accident. Those of us endowed with the power to see, and the power to be taken seriously when we talk about what we see, arrive at these powers discursively, via language. Haraway says that we must “become answerable for what we learn how to see”.

The inadequacy of vision makes itself felt throughout the show, often quite literally. Upon entering the gallery, one is greeted with a kind of blockage. In front of the door, cutting through what otherwise would be an intuitive path into the Adam’s top floor gallery, is a purple PVC curtain. Things are barely visible behind it. Or rather, it’s possible to make out where, behind the curtain, light comes from and where objects block that light from reaching the viewer. The curtain sets a scene. It casts everything in pink, and provides an indication that this is a show in which things don’t fully reveal themselves. Our view is partial. Things are never able to be completely comprehended.

Elsewhere, curtains provide a kind of stage, as with a row of aluminium chains, in pink with their bottom ends dipped in green, hanging in front of another set of Hopf’s snakes. Or they hide other works, as with a peach-coloured mesh, patterned with white wavy lines, which one must pass by before Hopf’s video Lily’s Laptop (2013) – in which a babysitter gleefully floods a comfortable middle class apartment – comes into full view. Or they hide nothing and reveal nothing, as with a peach mesh that hangs against a wall from the ceiling of the top floor, and gathers in a neat pile on the ground of the bottom floor.

Sometimes, works spill out, overlap, or interrupt one another, or you find yourself implicated in another’s experience. This is the case with a series of audio works triggered by sensors, in which Buchanan intones an elliptical, speculative commentary. When someone else activates a sensor somewhere else in the gallery, Buchanan’s voice multiplies, creating a call and response across the building, and reminding you of other bodies navigating through the space. One two occasions, I was joined by another when listening. Both times, the other person stood a comfortable distance away, but we found ourselves bound into a fleeting kind of intimacy – them reliant on my presence in front of the sensor to activate the work; me knowing that if I stepped away, they would miss some of the audio, and might find themselves leaping to catch up, or waiting for the track to loop to reveal what was left out.

The content of the audio works sets a scene, establishing a framework through which reading and viewing can take place. In the first, she says, “This is a diagram … a body, a wave, a camera, this is history, and a knife, a cutting.” She speaks of “systems, systems, systems”. But systems are almost always impossible to illustrate, to imagine, to turn into diagrams. It is almost always easier to illustrate the outcomes of systems than it is to realise the systems themselves in a comprehensible form. Wex’s work illustrates outcomes of a process of repeated performance, invisibly maintained through disciplinary ends, and though the archive it draws from stretches back to Greek and Roman statuary, it remains difficult to render the system by which this performance reproduces itself, to imagine what it might look like if it were laid out. The system, the structure, the network – these things hover over language, refusing to attach themselves to a manageable means of signification. But this space, between signifier and signified, between the address and the recognition of oneself as addressed, is fertile in its own way.

In an audio work situated between Wex’s work and a mirror, Buchanan engages with Haraway’s essay, albeit somewhat obliquely.[2] Buchanan says, “In her reading, the refusal of female identity of necessity harbours a moment of articulation of that identity … Conversely, refusal of all identification may result in quietism, or internal exile. It is the space where identification is performed, authorised, or broken which may be more relevant. Or, to put it simply, there was much less mirror than he was used to.” She speaks quickly, but also in a manner that is measured and resolute. And what she says, in a way, anticipates the kind of disidentification my friend described, making the response seem accounted for, mapped, deliberately teased out. So, if the structure of being gendered, or the network of power in which the gendered body comes into being, struggles to be illustrated directly, and if its outcomes (as in Wex’s work) become almost unbearable when brought into representation, it may be the breakages, or slippages, or glitches in identification, disidentification, addresses, and their responses that allow for the partial, inadequate means of seeing we inherit to be made strange, repaired, or even embraced.

All photographs by Shaun Waugh. Courtesy of Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi.

Editor’s note: A second show by Ruth Buchanan, The actual and its document, is on at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery from 10 September to 4 December 2016.

Ruth Buchanan, Judith Hopf, Marianne Wex

Bad Visual Systems

Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi

2 October to 22 December 2016

Free admission

[1] This is the title given to the anthologised version of the essay. The essay was originally published as ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’.

[2] Buchanan engages with Haraway through the writing of two other women, art historian Susanne von Falkenhausen, and writer Marina Vishmidt.