Baby and Fire

On collective curation reframing the experience of toi Māori at the arts institution.

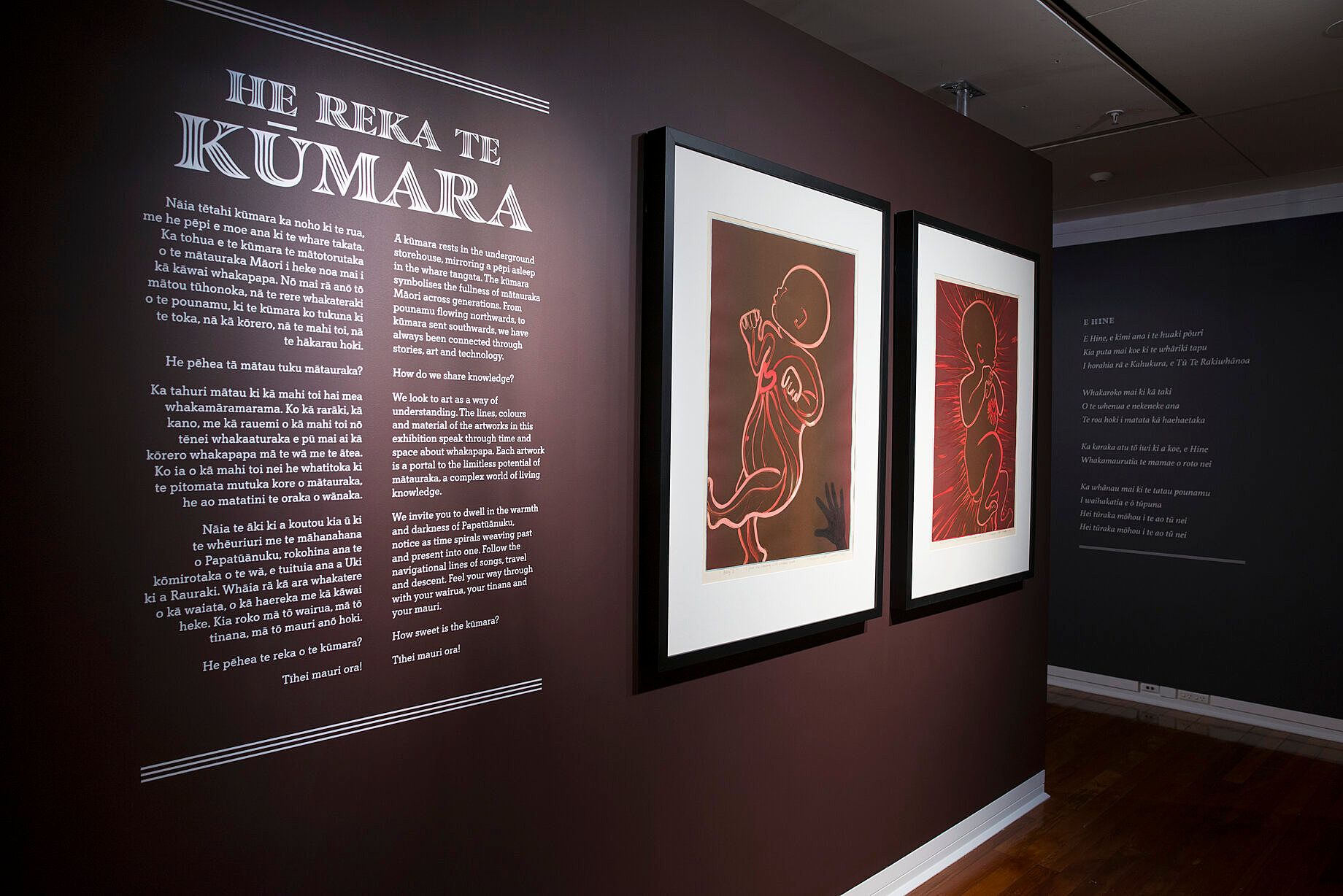

Baby 3 floats in a reddish-brown color field. Luminous pink brushstrokes form the silhouette and trace the veins and arteries connecting to the heart. This baby isn’t constrained by the form of the uterus. Instead, their legs are unfurled and kicking, swimming through an indeterminate space. The shadow of a traced hand anchors the right side of the composition; it's one of those universal images that you can almost feel, recalling the texture of paper under your hand while a ticklish outline is drawn around it. Baby and Fire glows like an ember next to Baby 3, the same subject and palette but encircled with urgent radiating lines, heart exposed as a burning symbol of love and passion. It’s hard to know what direction the lines are flowing. Do they signify energy absorbed inwards or emanating out from the body?

Baby 3 and Baby and Fire are monotype prints, carefully considered free-hand drawings, applied in paint directly onto the printing plate. When I look at them, I think of Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung's description of the body as the ‘primary museum’, the assertion that “if a museum is a space in which knowledges are kept and disseminated, then the body is that quintessential space of cognition and experience.”

Marilynn Webb (Ngāti Kahu, Te Roroa) is an important figure for the four artists who curated this exhibition

These two works by Marilynn Webb (Ngāti Kahu, Te Roroa), made in 1990, open the exhibition He reka te Kūmara. Webb, who lived in Ōtepoti for much of her life, primarily working with prints and pastels, is an important figure for the four artists who curated this exhibition: Piupiu Maya Turei (Ngāti Kahungunu, Rangitāne, Te Ātihaunui-a-Pāpārangi), Madison Kelly (Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe), Mya Morrison Middleton (Ngāi Tūāhuriri, Ngāi Tahu) and Aroha Novak (Ngāi te Rangi, Tūhoe, Ngāti Kahungunu), who have positioned Baby 3 and Baby and Fire as pou of their exhibition and project. Like many of the artworks they have included, I feel their interest is not only in the subject of the work, but also in the person who made it, what they stand for in terms of Māori art history and a local Ōtepoti art history.

The prints describe potential, a period of development, or something that is still in the process of coming into being. The traced outline of a hand is a motif often repeated in Webb’s works. Discussing Webb’s inclusion of herself and her own body within her work, Bridie Lonie describes the function of hands as follows:

With their hands artists make and unmake, care for their children and their parents. Webb’s use of the silhouette of hands aligns her with artists of past millenia.1

This expanded idea of ‘the artist’s hand’ is a through line within He reka te Kūmara, as it is turned to the mundane and vitally important work of daily life, a profound way to connect to our ancestors and descendants through the practice of making art.

He reka te Kūmara, installation view, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, 2021

This exhibition is the culmination of research undertaken during Piupiu Turei’s time as curatorial intern at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery (DPAG), during which Turei decided to invite Kelly, Morrison Middleton and Novak to become part of a collective curatorial group for the show. In saying this, I read He reka te Kūmara as more of an artistic project, an intervention into the DPAG and its collection by four artists who have used the resources and space supplied by the institution as an opportunity to research, be in wānanga with one another, and connect with mātauranga Māori. He reka te Kūmara also sits within a wider context. Ngāi Tahu artist collective Paemanu recently opened Hurahia ana kā Whetū – their own intervention into the collection of the DPAG – and Paemanu: Tauraka Toi, an exhibition of new work by Ngāi Tahu artists, including Kelly and Morrison Middleton. Essentially, at this moment, the gallery is full of toi Māori, the outcome of a years-long engagement and negotiation between Paemanu and the institution.

He reka te Kūmara is built with pre-existing work, including some of the most significant figures of recent Māori art history

He reka te Kūmara is built with pre-existing work, including some of the most significant figures of recent Māori art history, and houses a complex layering of artworks, objects and texts. In addition to prints by Webb is a suite of life drawings by Ralph Hotere (Te Aupōuri, Te Rarawa), a large-scale vanitas photograph by Fiona Pardington (Ngāi Tahu, Kāti Mamoe, Ngāti Kahungunu, Clan Cameron of Erracht), an amorphous polystyrene sculpture by Peter Robinson (Kāi Tahu), and pendants and wall drawings by Areta Wilkinson (Ngāti Irakehu, Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke, Ngāi Tūāhuriri). There are maquettes for works by Matt Pine (Te Ātiawa, Te Āti Hau Nui-a-Pāpārangi, Ngāti Tūwharetoa) and Shona Rapira Davies (Ngāti Wai ki Aotea), which link to larger sculptural works outside of the gallery context. Weaving and textiles by Georgina May Young (Te Upokorehe, Whakatōhea, Irish) and a moving-image work by Aydriannah Tuiali‘i (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Hāmoa) represent a younger generation of practice featured in this exhibition. Also included is writing by HK Taiaroa (Ngāi Te Ruahikihiki, Ngāti Rangiwhakaputa), digital resources supplied by Ngāi Tahu iwi organisation Kotahi Mano Kāika, and a reading room.

He reka te Kūmara, reading and audio nook, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, 2021

The gallery has been painted the deep reddish-brown found in Webb’s prints, which adds to a closed in and intimate feeling. Tuiali‘i’s work Kōwhai (2017) habitually fills the space with sound. Text is a prominent feature of the curatorial approach, including the words of waiata that are applied to the walls in coloured vinyl. There’s a touch screen where you can scroll through, listen to and read the words of waiata recorded by Kotahi Mano Kāika. Authorship of the wall labels has been divided between the members of curatorial group. The labels are based on personal readings of the artworks, which spiral out to broader epistemological views linking to land and pūrakau. The exhibition is not necessarily focused on the individual works per se, but rather a personal art history created by bringing them together.

It’s also important to acknowledge the other shaping force of this project, which is its location. I’ve only recently moved to Ōtepoti, but I have spent most of my life on Te Waipounamu. In this show, I recognise both Ngāi Tahu mana whenua and artists who don’t share that whakapapa connection, but who have other important relationships with the south. Artists like Hotere, Rapira Davies and Webb hold a special place in Ōtepoti, even though they whakapapa to Te Tai Tokerau. Ōtepoti is a place where these artists have lived and worked, and their works remain particularly visible, hanging in buildings and public spaces throughout the city. Members of the curatorial group have all lived here for significant periods of time and have been influenced by that, so it’s understandable that they would want to celebrate an art history that is specifically Ōtepoti in character. I see this group of artists collectively turning their hands to curation, especially within the DPAG collection and with existing works, as a communal way to reckon with our art-historical canon. It’s rare to see all your heroes in one room together and rarer still to be able to engage with these collections, artworks and artists in the hands-on way Turei, Kelly, Morrison Middleton and Novak have been able to.

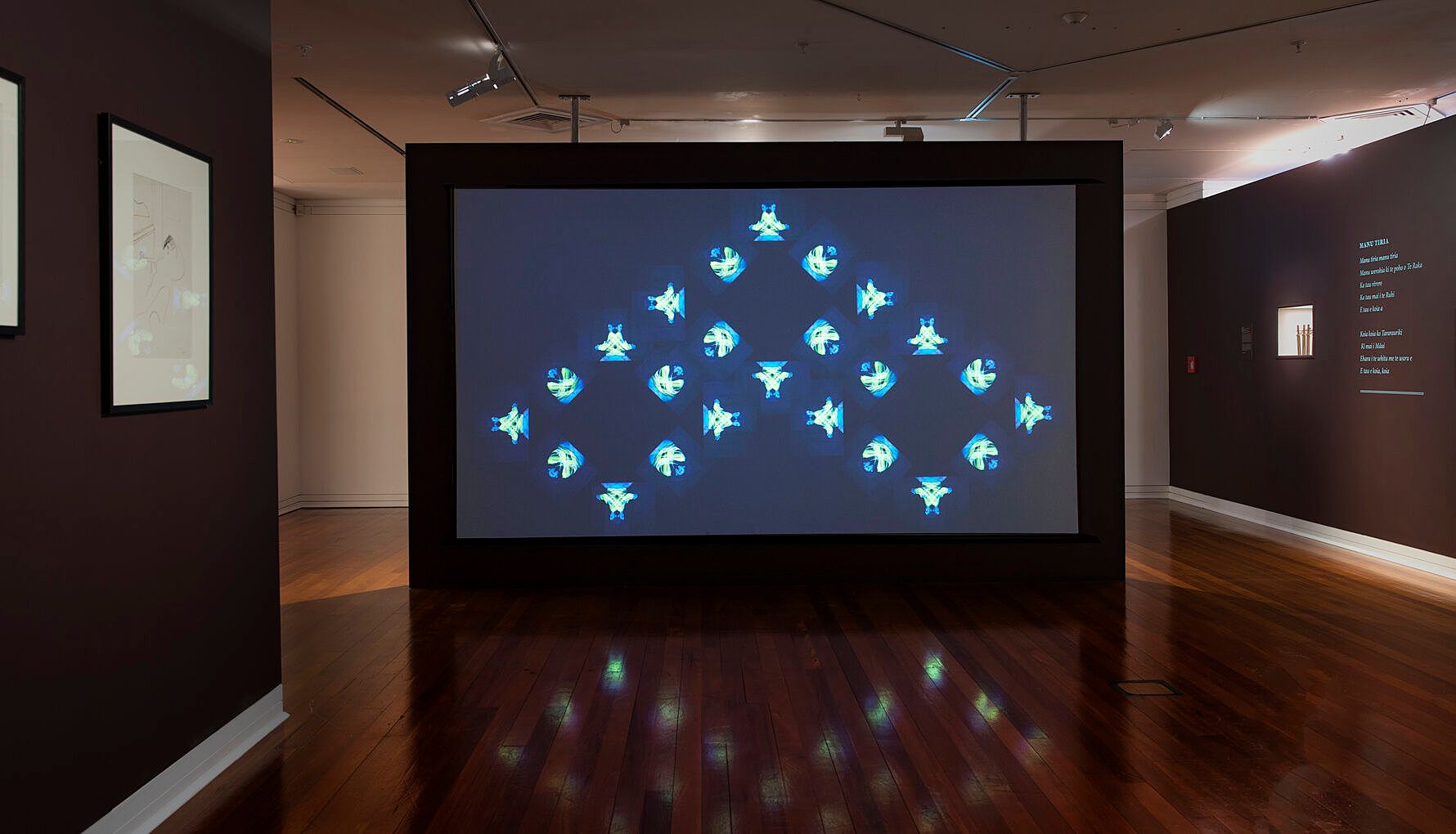

Aydriannah Tuiali‘i, Kōwhai, 2017, in He reka te Kūmara, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, 2021

As artists, the curatorial group have all previously had the experience of making work for the gallery environment, or what Ndikung terms ‘the secondary museum’. The process of making that work is an embodied one, not too different from what they have done here in shaping the exhibition. It is worth noting that, as artists, we are also in turn shaped through that process of making art, we are shaped by our research and the knowledge we choose to pursue. There are times when the curatorial reasoning or narrative in He reka te Kūmara can seem opaque. Still, the function of the project is not only related to the exhibition itself, but the ways in which the curatorial group has been able to grow their collective knowledge. Through the exhibition, they are trying to share some part of what they have learned with the audience, which has led to this textually dense environment with printed resources in the reading room and complex labels. In some ways, He reka te Kūmara reminds me of looking in someone else's workbook, which is full of personal notation and brimming with a bunch of ideas in different stages of being processed. When I watch Tuiali‘i’s work, in which she sings and performs the actions of the karakia ‘Ko te Pū’, recounting the world’s creation, I think not only about the process of creation but the challenges of being a learner. How it feels to be at a reo wānanga, trying to make those actions with my own hands while trying to keep the words and tune in my head.

As artists, we are also in turn shaped through that process of making art

The title Baby 3 suggests that there is at least one other print in Webb’s monoprint series, not shown with the two pou of the exhibition, and in actual fact, these works are part of a much larger suite featuring the same subject. In terms of the baby’s identity, it could possibly be Webb's son, though he was born thirteen years before the creation of these works, which leads us to the question of why Webb chose to ruminate on the figure of the baby at that particular time. I don’t know the answer to that, it belongs to her own personal history, but in He reka te Kūmara the group has placed these prints as the first artworks seen when entering the show. They are a symbol of burgeoning life, the embodied nature of learning, and the limitless potential of mātauranga. They remind us that learning is an ongoing process, one that we start over and over again at different times in our lives.

1 Bridie Lonie and Marilynn Webb, Marilynn Webb: Prints and Pastels (Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2003), 47.

Feature image: Marilynn Webb, Baby 3, 1990, in He reka te Kūmara, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, 2021