In Which I Try to Avoid the Subject

Vanessa Mei writes on violence and vantage points as an adult survivor of childhood sexual abuse.

TW: Mentions of childhood sexual abuse, vomiting

When is violence not recognised as violence? When the witness providing testimony is silent. When every single tree in a forest falls and the community remarks, how loud the cicadas have been, how brazen and bizarre the behaviour of small animals, but do not connect this occurrence to the act of creatures being vacated from their homes. To the animals before them who have had the vibrations of a chainsaw hardwired into the rhythm of their wings. Who felled the forests? Could they, too, be considered victims of a wider circumstance?

On the occasion of turning 26, I post a quote on social media by the artist Xin Cheng, excerpted from the publication Following the Rubber Trails, in conversation with philosopher Heidi Salaverría. It helps me to comprehend my own experiences of violence, and the way that violence can be interpreted differently depending on whose purview you are getting.

Cheng writes:

I would catch an ant, drop it onto the web woven in the corner of the stairs, and watch: how the spider, first startled, hurried to the struggling ant, wrapping it up in its silky cocoon, then sucking the juice out of it. What would it be like, to be an ant, dying? Or how would it feel like to be the spider where most of the day seems to be about waiting, stillness, and sudden bursts of action? These are reminders of other realities, existing in parallel to my daily life of solving arithmetic riddles of counting rabbit heads and chicken legs. I didn’t know that Jacob von Uexküll, the Baltic-German biologist who introduced the concept of ‘environment’ in 1926, had asked the same question and worked out that, in any given environment, there are infinite possible perceptual worlds, depending on whose perspective you see through.

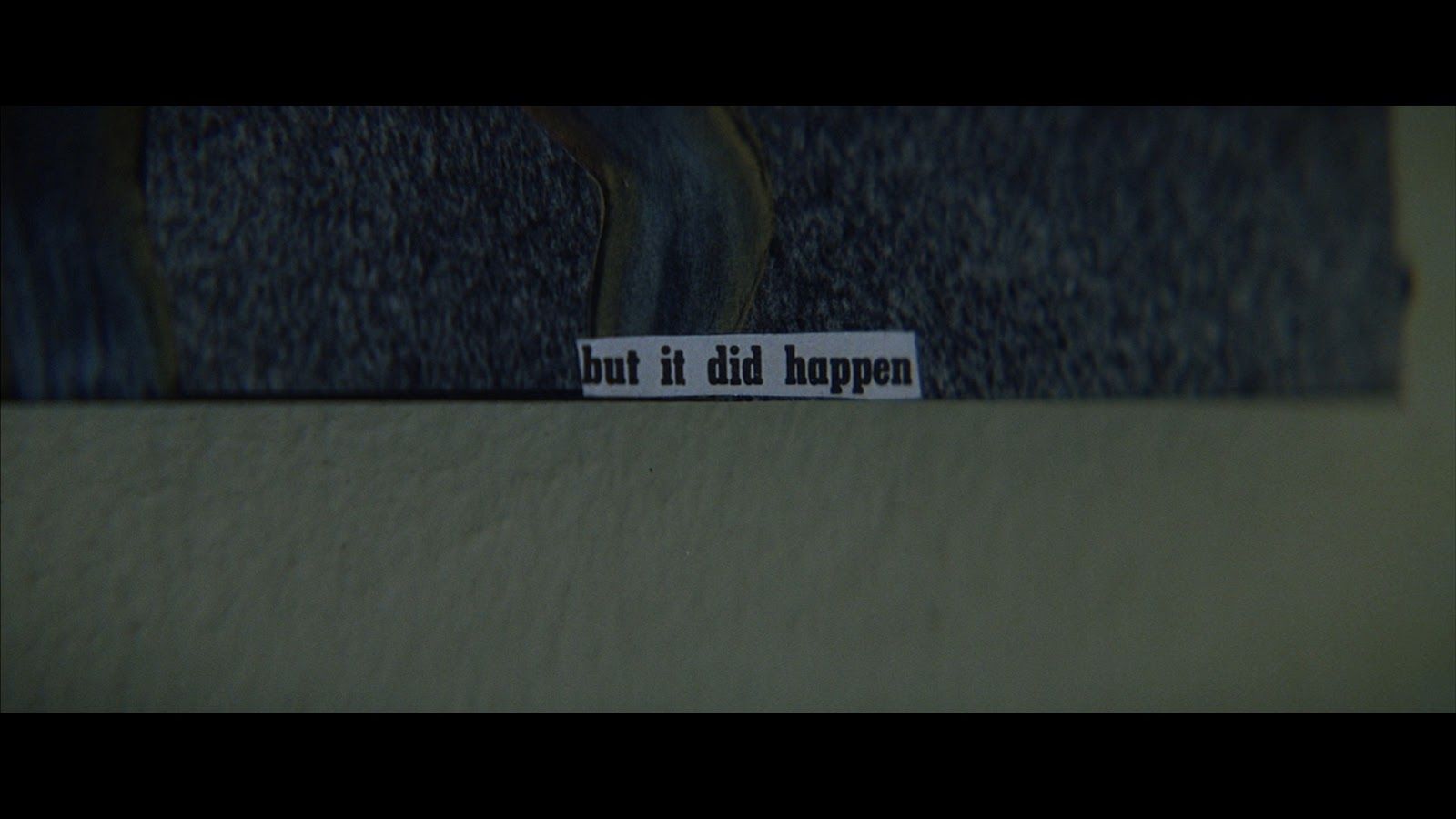

When I compare the vantage point I possess as a sexually empowered, trauma-educated, hotly self-aware nb adult, it is a celestial cosmos away from the power I was dispossessed of as a young person suffering under the cruel reality of girlhood. Through metaphor, I breach the distance it takes to speak openly on the sexual abuse I experienced – throughout my youth – but mostly about the omitted part, the experience of being a child captive at the hands of a larger mammal. Warped by time, relationship and memory, my perspective of these events is infinitely different from the pov of other people. There are those who may dispute and shut down this perception of this truth because it negates their own. Be that as it may,

Magnolia (1999), Paul Thomas Anderson.

I attempt this story from its aftermath. From the discovery of being a living matryoshka doll, one descendant from a long, long line of many: a girl-child trapped inside a teenage heart trapped inside a young adult, inside a body that rejects touch, a body that falls ill, a body that shakes but cannot weep, a body that prayed to never blossom, a body that has lent itself to the pursuit of advantage-seekers seeking advantage, who has no concrete proof of what has happened to them except the certainty of the pain they have felt in their body. Like most adult survivors of traumatic childhood experiences, I have been a forest of vacated animals.

My keen reflexes allow me to dissolve from the world slowly, and then all at once. This un-reality forms an exoskeleton over my emotions that can press the electrocute button on my sense of self and identity. It’s a means of retaining one’s sanity, learned early on, by logging out entirely. Because of this there are huge blips in my memory. Days of complete inattendance. No chorus of birds. Just stretches of time where the spirit drifted along the ether, severed from the body.

My dissociation is also a refusal to inhabit an unremarkable reality, to hand over the injustice of my disembodiment to anyone else’s satisfaction.

Now that I have language I wish to speak, now that I have a body alive to touch, how do I communicate that which these bones have been incapable of holding inside of memory? Experiences that are repressed and refracted, events the brain chose to keep off-record – a truth I had kept myself away from for nearly two decades. How do I betray my own safekeeping, when using my voice feels like a shameful betrayal of its deepest pathologies?

For someone who means to be a writer, I don’t write much. I avoid writing if I can. Avoid the sense of being unpeeled like an onion, pinned to the floor with the literality of meaning, of seeing the reflection of my own experiences escape onto the dance floor. I never write about this topic, even as it hovers over my doorstep, creeps into the black space of metaphor, hides underneath the floorboards of my poetry.

At a New Year’s party my stomach gurgles expressively. Total discontent at my decisions from the past six hours. It’s brave for a person with IBS to go on a booze bender. I pick myself up and walk calmly to the bathroom, My booty is clenched as tightly as I can muster. As soon as the door closes, I throw up copiously, eyes wet with involuntary tears. After the expelling, I perform a disappearance: wipe down the toilet seat, spritz the bathroom with air freshener, wash my face, redo my eyeliner. Re-enter the living room. My boyfriend still where I left him. Nobody has noticed my absence, I have given them no reason to. “How you going?” he asks casually, and I nestle into his side, my smile bright and wide. I’m absolutely fine.

Like this I hold steadfast the secrets of my body. This chain reaction of concealing my vulnerabilities from others occurs so abruptly that I don’t always recognise until long afterward how many details I have reflexively suppressed. It never occurs to me that I should inform somebody if something is off – I mean, why should I? What could they do?

I have a different story about puking my guts out, which has a different ending. After an extensive time in trauma recovery, while I’ve had flirtationships with all genders (and more than my earthly fair share of soul-changing, life-giving friendships), my then current, now previous partner is the first serious romantic relationship I’ve been capable of maintaining, of withstanding those deep initial rollercoasters of fear to trust enough to be intimate with. Trust and intimacy not so easy for a neurotic themme fatale like me. One evening, I drink too much at his flat’s house party and throw up my sense of self all over his bedroom. Chunks of vomit cling to the polished wooden floors, the t-shirt I am borrowing, everything I can see.

While I am in the shower, he wipes the floor clean. Not an act of concealment, but one of someone showing care towards me. We lie in bed, the rest of the party disappearing. And it’s like puking my guts out in front of him is so deeply embarrassing that I might as well just open up about the other stuff. “I’m pretty sure that my [ ] is autistic,” I speak slowly, “and you have mentioned before that our behaviours are really similar.” I take a breath. “I’m nonbinary.” He nods. I pause for a long time. Close my eyes and choose my next words carefully. “There’s probably another thing I should tell you.”

Untitled, Vanessa Mei, 2017

Being who I am, a human being like everybody else, I’m unable to vivisect my experience of the world into singular identities. For me, the queerness blends into the neurodivergence, which mirrors and echoes the trauma, which affects me physically – hence all of the stories about puking my guts out – and then add to that the complications and inversions of race, ethnicity, class, size and gender, each their own universe bouncing off of each other, a never-ending Venn diagram of centres.

What follows, the very first time I tell someone my secret, is a passage of complete darkness. Spectres appear at my window every night for a fortnight. They’ve been there, hiding in the dark, for as long as I can remember. Their faces are contorted shadows, never letting up, rattling the curtains and smashing the glass, waiting for me to let down my guard. I do not pass gently into the night: I have literal ghouls trying to break inside. I am going through what some might call a psychotic breakdown. But I do eventually lower my eyelids. And wake up, rubbing my lashes, when the light of day shines across my face.

“Did he touch you?” asks my mother, so quiet that I can barely hear her asking.

We are parked next to the field, where I have run away for the evening. I fidget in the back seat. “I don’t think so,” I say, and it is true. But there are clues everywhere to my story.

This essay was originally commissioned and presented as part of the event Speaking the Unspoken: Words I Should Have Shared, for Samesame But Different, 2023