How to Enter a Book?: A response to Aukati

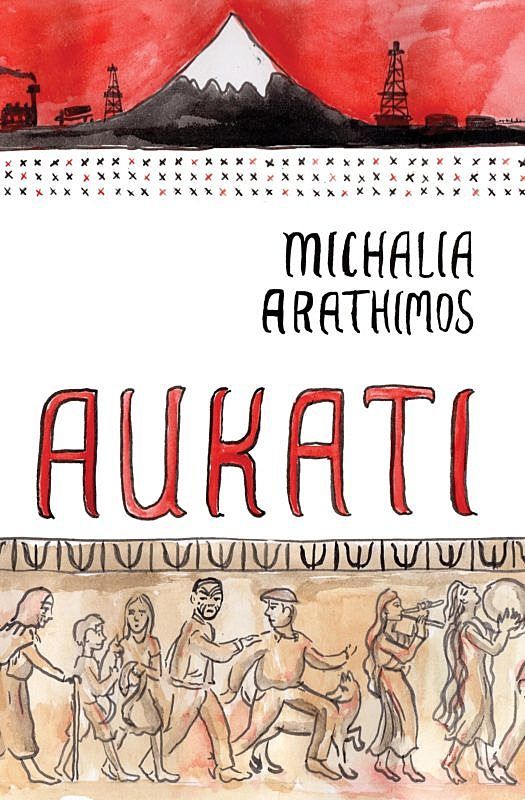

Antony Millen responds to Michalia Arathimos' debut novel Aukati and finds a complex relationship forms between himself and the story.

Antony Millen responds to Michalia Arathimos' debut novel Aukati and finds a complex relationship forms between himself and the story.

Entering a book is like shifting into a new neighbourhood, starting a new job, getting married, or crossing a marae ātea for the first time. How you enter influences your subsequent relationship with the people and situations you encounter inside.

I entered Michalia Arathimos’ debut novel, Aukati, as a writer with similar interests. I live in the King Country, home of the most famous aukati in New Zealand memory, that drawn by the second Māori King, Tāwhiao. I’ve written a short story with the title, ‘Aukati,’ for Landfall. The idea of a line drawn in the sand, separating ‘us’ from ‘them,’ accompanied by the harsh consequences for crossing that line, intrigues my imagination.

In Arathimos’ writing, I encountered a mind fascinated with concepts that I have explored, extending to other aspects of Te Ao Māori: integration of manuhiri with tangata whenua; the place of spiritual phenomenon in modern contexts; and corporate impositions on indigenous land and its disastrous effects on natural environments. Even better, we both touch on themes of space and time, the immigrant experience in Aotearoa New Zealand, and mass surveillance. But the notion of aukati, of drawing a boundary or line, appeared to me as woven into every aspect of the novel.

The notion of aukati, of drawing a boundary or line, appeared to me as woven into every aspect of the novel.

Fittingly, Aukati begins with a pōwhiri, a ritual designed to inaugurate new relationships with those who reside inside. In this case the tangata whenua belong to an unnamed marae near the Taranaki coast. The manuhiri are a collection of activists joining with local iwi to protest fracking nearby.

Among the protesters are our two protagonists. Alexia is a second generation Greek New Zealander, and a law student nearing the end of her degree in Auckland. In an awkward moment, some confuse her as Māori and prompt her to lead the waiata. Isaiah is an activist returning to the marae of his father, one he has never visited. He is brought onto the marae by a cousin, skipping the formalities of the pōwhiri as he is already tangata whenua by birth. The manners in which Alexia and Isaiah enter the community foreshadow much of their experience within it.

Writing from inside Te Ao Māori skirts the line for writers like me, a Canadian New Zealander, and Arathimos, a Greek New Zealander, in light of contemporary controversy regarding cultural appropriation. It was encouraging to see Arathimos immerse herself boldly, though I discovered later she has some impressive backing credentials.

The literal, modern aukati in the book is the boundary around the fracking site, a farm settled a century before on Māori land. Arathimos connects this with an aukati drawn by Isaiah’s ancestors whose territories were once demarcated by the river and the mountain, an attempt to stop the encroachment by Pakeha:

‘You’ve heard about the aukati? The line the soldiers forced the people back to in the 1800s? That’s away over there in the bush. The people won’t set foot there. But this stone marks the place where they killed their chief … Every local who walks past this place, this is what they’re thinking: that’s the place they murdered him. There’s blood all over this land – their blood and the Crown’s. They live it every day. History’s not separate for them. And it’s still going on – the injustice. It’s more insidious now: it’s chemicals and pollution, not guns. You can’t tell me it doesn’t make you want to fight.’

This physical aukati extends to the metaphysical. Alexia is not only a talented singer, she is also gifted with a Miles Davis-like synaesthesia, the ability to see sound as colours. It’s a curious trait and one that opens the novel’s world to other possibilities, namely kaitiaki in the form of taniwha and patupaiarehe.

A more figurative aukati is that of the rule of law. From the outset, it is unclear what Alexia’s place is in the protest movement. Initially, she is pressured into using her voice for fundraising efforts. However, her more influential and longer-lasting contribution is attributed to her law studies:

If the place and the people and the processes here were all new to her, at least this wasn’t, this taking of legalese and bending it to her will, these small acts of translation. This was the secret Alexia had discovered about the law: it was really only another language, merely a series of agreed-upon rules. You could take these rules and re-interpret them, or use them as a scaffolding for new ideas. But for the most part the practice of the law was about adhering to a script. And she had always been good at adhering to the rules, until recently.

Crossing an aukati in the wrong manner involves breaking someone else’s rules, someone else’s idea of right and wrong, with the risk of experiencing their consequences. The group is faced with a classic dilemma for activist groups, one famously remembered in this part of the world: if and when to use violence. Arathimos deposits us in these discussions, revealing no authorial bias, allowing us to witness the in-fighting over plans and strategies and the spontaneity of rogue members who go off script:

‘Called me a fascist,’ she said. ‘So I called him a cultural imperialist guilty of micro and macro aggressions. That shut him right up.’

‘That’s what shut him up?’ Rangi said. ‘Thought it was my boot up his arse.’

Aukati separate and divide, but they also connect and define. Alexia has been raised in the centre of a circle of relatives and has joined this band, in part, as an escape from her family’s insistence that she cares for her widowed grandmother. In this way, she draws a line in an attempt to pursue an identity of her own. Such separations have their consequences:

What kind of space does the absence of a person leave in life? … The shape of the space was up to the person left behind. You could allow it to be a defining thing, like a scar on your skin or a patch on your sleeve. You could allow it to undermine you invisibly at unexpected moments, as when the sand drops off suddenly under your feet in the surf. Or you could allow the space to eat you, like some kind of viral nothingness. The size of the wound was up to you.

Scars, patches, wounds – all analogous of the fracking in the novel and the wounds in the earth.

So, of course, aukati are everywhere in the book, as they are in life. That’s why it’s such an engaging concept, and one which intrigued me throughout.

However, as I ventured into the middle sections, I realised an unfortunate thing: I wasn’t empathising with the characters. I wasn’t caring about them, or about their success or failure in their activism activities, or about their relationships, even the core romantic relationship between Isaiah and Alexia. I wanted to blame the writer for this and found some justification as the story seemed to lag in the middle, with a multitude of meeting scenes, and an overabundance of passive sentences.

I considered my initial approach to my reading – not entering the story with my heart, but with my head.

At the same time, Arathimos was doing everything right to create empathy, including alternating perspectives, dying relatives, damage to the environment, back stories, and historical accounts of alienation and colonisation. So, I considered my initial approach to my reading – not entering the story with my heart, but with my head. Once I recognised this and started opening up, I did feel empathy for the protesters in their conflicts in front of the courthouse. I certainly felt bad for the eels and the community whose kai moana was degraded by the fracking activities. Arathimos uses the loss of Alexia’s grandfather and her subsequent grief to open the marae community to her presence. This was done to great effect.

Still, I never fully connected with Alexia or Isaiah. Like Romeo and Juliet or Danny and Sandy in Grease, the young lovers’ complex personalities are overshadowed by the somewhat stereotypical yet more charismatic supporting figures of Sam, Rangi, and Polly.

Overall, Arathimos, writes clean and elegant prose. The plot is generally fast-paced, aided by short chapters, each with a distinct purpose achieved masterfully every time. It’s technically excellent in structure with a satisfying, realistic, and complex ending, allowing us to experience the public and heart-breaking consequences of the group’s defiance of the powers-that-be.

The political and environmental aspects run deep in her characters’ lives and point us back to our own reality.

In exchange for her character-driven story-telling and complex thematic expositions, Arathimos wants something from her readers, something more than an intellectual engagement with literary fiction, and more, even, than empathy for her characters. The political and environmental aspects run deep in her characters’ lives and point us back to our own reality.

Recognising this, I became wary. It’s my nature, as a reader, to guard against certain authorial agenda intruding into the narrative. There are several provocative incidents that made me question the credibility of the narrative and prompted me to do some fact-checking. The police do not come off well in this book, nor does the media:

It was marked as a crime site. They would outline a damaged truck in white; they would photograph this piece of private property because a company owned it. But no one wanted to publish his photographs of dead birds, the damaged land lying open and oozing fluid, toxic chemicals leaching into the earth.

Statements like these, while profound, do make me question if other sides are being given their due. That is not to say we should see the other sides in the story. We are, rightly so, viewing everything through the lens of the activists.

Looking further outside the text, I was surprised to discover that fracking has been happening in New Zealand for the past 27 years, mainly in Taranaki. As the book illustrates, fracking carries concerns about water pollution and seismicity, concerns considered unfounded by government and some scientific agencies. Adding to that, I could not find any precedence for some of the police behaviours at the group’s first protest at the courthouse.

However, immediately after finishing Aukati I read an article about Rangi Kemara in the New Zealand Herald, a commemoration of the events in Ruatoki ten years ago. In the article, I learned that Historian Harawira Pearless linked Ruatoki to Parihaka in 1881 in a Master's thesis. Arathimos cites both these incidents in her notes at the end of her novel. This discovery alone reshaped my experience of the novel even after I’d finished reading it.

Arathimos also has a personal connection to the events. Her partner was an environmental activist, arrested at Ruatoki in 2007. His ancestors are from Taranaki and he is a descendant from Parihaka protesters. She even knows Rangi Kemara personally, citing him as her te reo proofreader for the book.

So, her novel presents insights into the life of a community whose intentions are misunderstood from the outside and who ultimately cross paths with the law.

How did learning this affect a wary mind like mine, a mind that entered a book looking for an intellectual experience, admittedly missed the emotional connections, but certainly was not looking to be persuaded by any political agendas? Without question, it validated my suspicions of bias, but at the same time it helped me appreciate a source on the inside of such happenings, in touch with stories that haven’t been told by media or official agencies. Who doesn’t love an insider’s view?

There is plenty to love about Aukati. Michalia Arathimos should be applauded for the intricate weaving she has done, complete with some flaws which, like all relationships, can serve to flavour things. However, all readers should be prepared for her challenge, her wero, voiced at the end of the last chapter:

But beyond the few days when the media would discuss what was happening in this place, Alexia wasn’t sure if, in the long run, anyone really cared.

Sometimes, once you enter, and the rituals of welcoming are complete, and you are better informed and better connected to the people and their issues inside, you will be expected to care enough to contribute. This is what deepens the relationship formed between a reader and a writer, the community on the marae, and even the citizenship of a nation.

Aukati is available from Mākaro Press.