Artistic Agency in Public Agencies

K. Emma Ng considers the possibilities and pressures in a new age of public art.

K. Emma Ng considers the possibilities and pressures in a new age of public art.

In 1976 New York City was in the midst of fiscal crisis. After a brush with bankruptcy the city was running on empty, its infrastructure crumbling. Among the artists working in this climate, Mierle Laderman Ukeles was making work about the labour of maintenance – born of her desire to unite her work as an artist and a mother beneath a single philosophy of care. For the exhibition Art<>World at the Whitney Museum of American Art that year, Ukeles invited each of the museum’s 300 maintenance workers to consider one hour of their daily work as “maintenance art,” gifting them pins to wear that declared "I Make Maintenance Art One Hour Every Day."

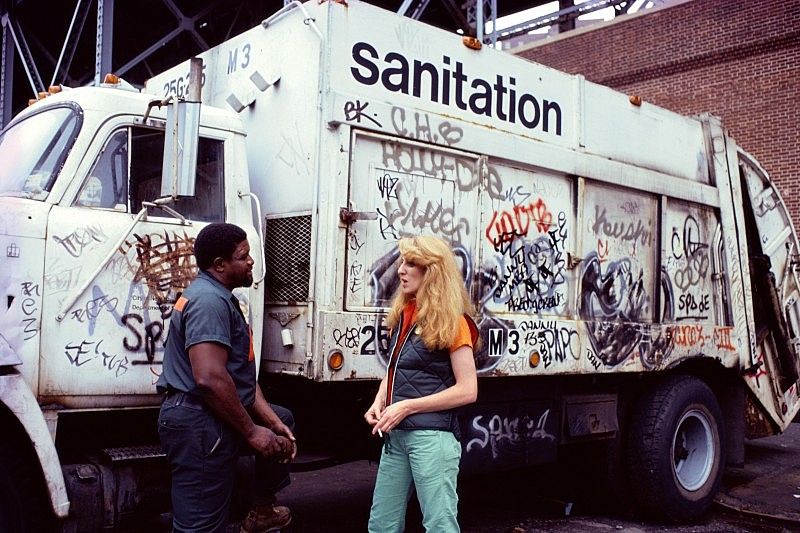

In reviewing the show for the Village Voice, art critic David Bourdon quipped that the cash-strapped New York Department of Sanitation might follow Ukeles’ lead, rebranding its staff as performance artists in order to access funding from the National Endowment for the Arts. And in 1977, after forwarding the newspaper clipping to the Sanitation Commissioner, Ukeles was appointed the Sanitation Department’s official artist in residence – a position she still holds today.

This was not a public agency without imagination. Throughout the 1960s the department had published their own magazine, Sweep, which, alongside retirement announcements and employee profiles, featured crosswords penned by the Sanitation Commissioner himself. Ukeles’ (unpaid) residency did not make the Sanitation Department eligible for the federal arts budget. But refreshingly, the arrangement doesn’t seem to have been burdened with the expectation that Ukeles would deliver measurable outcomes and quantifiable gains for the agency.

Given Ukeles’ practice of interpreting labour as art, it is ironic that the PAIR programme – emerging from a vastly different cultural and political climate – seeks instead to put art to work

Inspired by Ukeles, the City of New York launched a municipal residency programme in 2015, which places artists within city agencies. But unlike Ukeles’ self-initiated residency, the stated aim of the Public Artists in Residence (PAIR) scheme is to support artists to “propose and implement creative solutions to pressing civic challenges.” This problem-solving framework casts artists as members of design teams, often working as a type of cultural liaison between city agencies and communities. Given Ukeles’ practice of interpreting labour as art, it is ironic that the PAIR programme – emerging from a vastly different cultural and political climate – seeks instead to put art to work.

With these two poles in mind, this essay considers the potential of artists working within public agencies, as well as the impacts this arrangement can have on their agency as artists. But I want to note that I can only begin to scratch the surface of this topic, which sprawls across the realms of art, politics and urban design, touching on issues as complex and dispersed as gentrification and the notion of some sort of ‘essential’ artistic agency. And another disclaimer – I stick closely here to the subject of artists employed by public agencies, rather than considering all forms of public art including “plop art” and community-based arts projects, which tend to have a different genesis and chain of command.

The question of how artists shape cities has been a hot topic across Aotearoa this year. A few months ago, Auckland Council sought feedback on a draft plan that made little mention of arts and culture. Meanwhile, Wellington City Council pumped up its on-paper commitment to arts and culture, centring it as one of five pillars in their ten-year plan. And in Christchurch, these considerations go beyond hypothesis: since 2012 art and artists have been instrumentalised in a number of contentious ways as the post-quake city is shaped. The council there is also currently developing a ten-year arts strategy.

Here, art is certainly being put to work in the service of an overt civic agenda

Around the country, councils’ public art policies suggest a role for artists in shaping urban design (e.g. Auckland’s and Wellington’s), and numerous projects integrate art into the built environment. Recently in Auckland, O’Connell Street, Freyberg Place and the Ellen Melville Centre have all been refreshed. A Lisa Reihana sculpture adorns the façade of the Ellen Melville Centre, while in O’Connell Street a new reflective sculpture by Catherine Griffiths is suspended above the streetscape. The design of Freyberg Place goes a step further, the artist John Reynolds having collaborated closely with Isthmus Group and Stevens Lawson Architects to create a tiered plaza inspired by lava flows. Reynolds has described the space as “a participatory public installation” and “a civic artwork.” There is a clear belief here, on the part of the council, that artists can make public space more pleasurable, pay homage to the histories of a site, and give voice to the aspirations and identities of the city.

Consider also, the in-progress designs for Auckland’s City Rail Link stations. Simon Wilson wrote an illuminating piece for The New Zealand Herald about the design process: a collaboration between representatives of eight mana whenua and the Auckland Council’s arts and culture team, alongside Alt Group, Jasmax, designTRIBE and Grimshaw Architects. Wilson paints a lyrical picture of how future commuters might experience the stations, casting them as breathtaking works of functional art that express a shared cultural identity while also serving commuters. Here, art is certainly being put to work in the service of an overt civic agenda. The stations have been conceived to celebrate the local sites and their histories, weaving in symbols from te ao Māori to craft a cultural as well as physical commons.

The role of the artist was to service symbolism, etching the values of the era into the grooves of posterity

The layered symbolism of the proposed designs aligns them within the general provenance of public art. When I interviewed the American artist Mary Miss last year, she reminded me that throughout history artists have been commissioned as monument makers, shaping public spaces in towns and cities all over the world. Miss was one of the first PAIR artists, undertaking a residency at New York’s Department of Design and Construction in 2016. This followed a long career of engaging with public space, from her earthwork sculptures – which Rosalind Krauss used to open her influential 1979 essay “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” – to the establishment of her City as Living Laboratory studio in 2009. The monumental artworks that Miss was speaking of were, and are, bound to the agendas of their civic commissioners. The role of the artist was to service symbolism, etching the values of the era into the grooves of posterity.

Recognising public space as an ideological battleground, we are beginning to look twice at the sculptures we have passed by a thousand times before

Aotearoa is dotted with public artworks of this type, but we have begun to parse them with renewed scrutiny. Recognising public space as an ideological battleground, we are beginning to look twice at the sculptures we have passed by a thousand times before. Public art was one catalyst for the deadly white-supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017, which began when white nationalists protested the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee – a Confederate commander – from a local park. Here in Aotearoa, similar debates are playing out as we reconsider the art of the colonial project. In January a group attached an axe to the face of an Auckland statue that commemorates imperial and colonial soldiers who fought in the New Zealand Wars. They issued a statement calling the memorial a celebration of “the ongoing colonisation of Aotearoa, its lands and its peoples.”

It is natural that we reconsider public art as our shared values change. After all, the philosophy that generally underpins public art is that it delivers some sort of public good – a measure that shifts with every society’s paradigm. The intent of monuments is to collectively remember people or events that are seen to be significant, or to symbolise a shared identity. Public art has also been seen to elevate public space, bringing the enlightening influence of art to the masses – a purpose that curator Miwon Kwon has characterised as both patronising and a fantasy.

This could set a foundation for the arts to be incorporated into all branches of government, employed in concert with other strategies to respond to a range of policy issues

Public art depends most of all on the attitudes of its commissioning patrons, and in this respect we might be on the precipice of change. When Creative New Zealand released their latest New Zealanders and the Arts report in May, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, who holds the arts portfolio, penned an opinion piece for The New Zealand Herald about the holistic benefits of integrating arts and culture throughout society. And according to Grant Robertson (Finance and Associate Arts, Culture and Heritage Minister), the Government is looking to entrench arts and culture as a key measure of societal wellbeing. The Government’s proposed ‘Living Standards Framework’ is based on the idea that “whether New Zealanders are living fulfilling lives cannot be judged on GDP alone,” and would consider “natural,” “social,” and “human” capital alongside financial measures. This could set a foundation for the arts to be incorporated into all branches of government, employed in concert with other strategies to respond to a range of policy issues.

This would see our conception of public art shift away from being merely a finishing touch (the sculpture in the forecourt approach). Mary Miss advocates for public art that goes beyond the ‘Percent for Art’ scheme that has been used in New York City since 1982 – by including artists from the conception phase of a project, rather than introducing them late in the process to ornament already finished developments. The ‘Percent for Art’ model emerged concurrently in Finland and the United States during the early 1930s, and generally mandates that one percent of the budget for publicly funded development projects be spent on public artwork. In New York it has resulted in a wide variety of works ranging from mosaic murals to sculpture to architectural features.

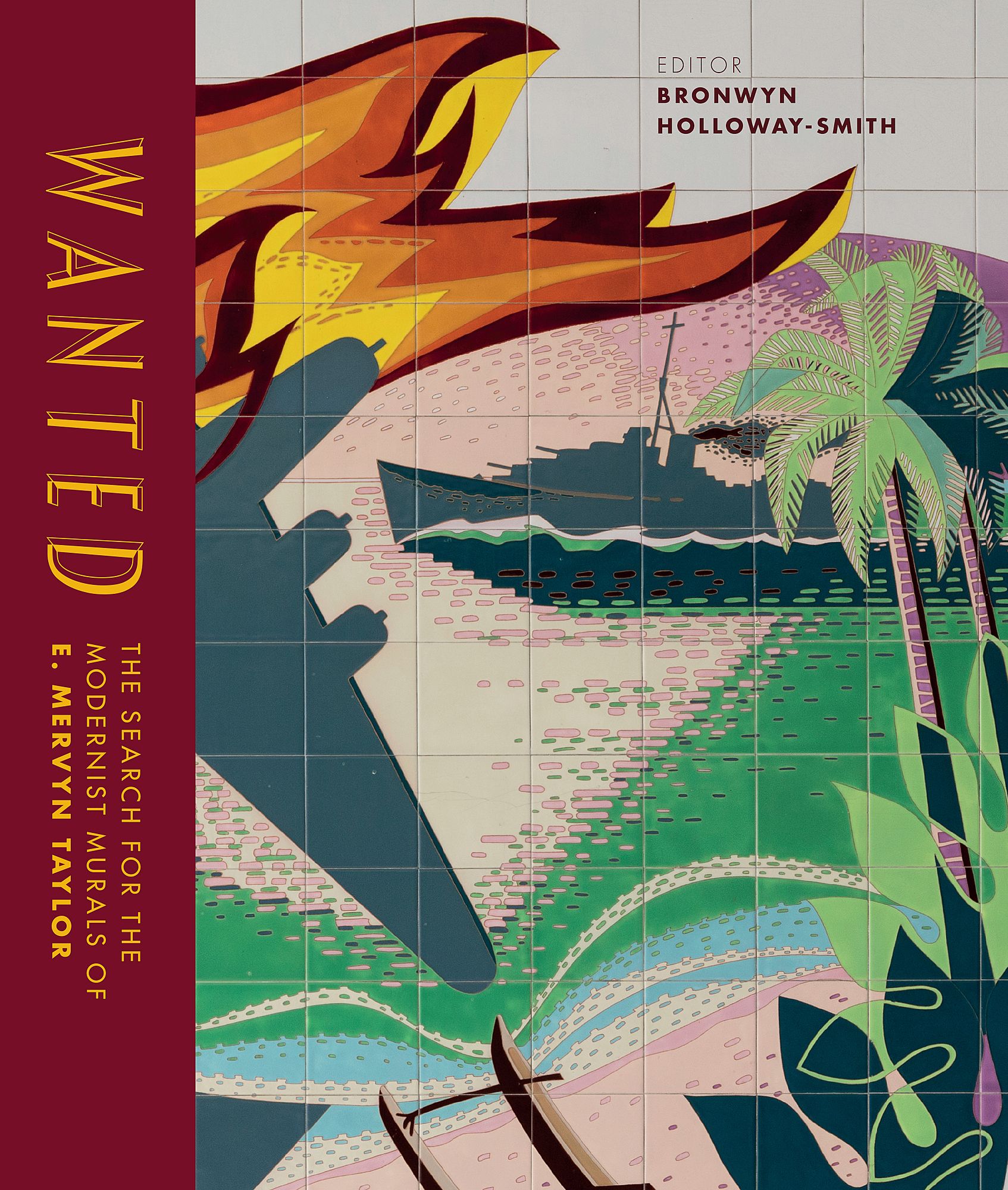

In Aotearoa, artist E. Mervyn Taylor – who was a member of both Wellington’s Architectural Centre and the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts – was a fierce mid-century advocate for such a scheme. Taylor’s belief in, and contribution to, public art have recently been highlighted in Wanted: The search for the modernist murals of E. Mervyn Taylor, a publication that emerged out of research undertaken by artist Bronwyn Holloway-Smith as part of her doctoral thesis at Massey University.

Taylor was just one of a handful of artists who made significant contributions to the urban landscape through public projects. In her introduction, Holloway-Smith lists Guy Ngan, Jim Allen, John Drawbridge, James Turkington, Roy Cowan, Russell Clark and Milan Mrkusich “among the set of artists who completed architecturally associated public art commissions as the idea caught on.” Ngan was even appointed to the staff of the Ministry of Works in 1955, thanks to the Government Architect Gordon Wilson’s enthusiasm for incorporating art into the development of public buildings.

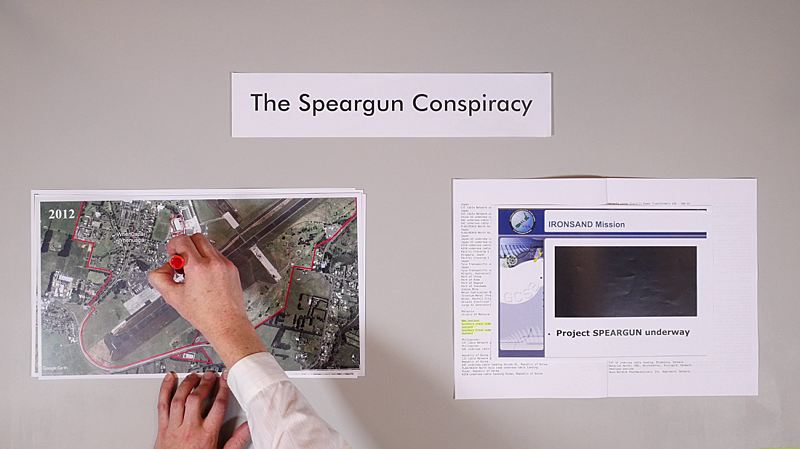

Wanted reads as a cautionary tale about forgetting the value of public art, and perhaps even as a lament for an era when public authorities (and corporations alike) saw value in commissioning ambitious artworks. The project was sparked when Holloway-Smith discovered that there had once been a mural by Taylor – Te Ika-a-Māui from 1961 – at the landing station for the Commonwealth Pacific telephone cable (COMPAC). After finding and restoring the mural’s tiles, Holloway-Smith proposed to create four of her own site-specific public artworks at the landing sites of the Southern Cross Cable, but was turned down by Spark who preferred to keep the sites as inconspicuous as possible.

Spark is a privatised descendent of the New Zealand Post Office, which commissioned Taylor’s original mural. Inspired by Taylor, Holloway-Smith sought to use art to engage the public, deepening understanding of the public’s stake in the cable and raising public consciousness of how digital information is controlled. This aim serves a kind of public good – one that is perhaps at odds with Spark’s own agendas. It’s easy to guess why, beyond security concerns around the site, they might have been reluctant to host these works: the public engagement and debate that might arise from such artworks – which would be considered a measure of their success as artworks – might draw attention to questions about the cable’s complicity in mass surveillance and other concerns.

In both form and intention, Holloway-Smith’s eventual artwork differs from the type of work E. Mervyn Taylor was making. Since Taylor’s death in 1964, artistic practice has evolved greatly, with social forms becoming more pronounced, and our understanding of public art has been reshaped to accommodate this. In the US, working with the Department of Design and Construction, Mary Miss was tasked with thinking about the ways that artists could contribute to civic life through the PAIR scheme. The three approaches she had developed, by the time that I interviewed her last year, cast artists as facilitators as well as makers, advancing an idea of public art inflected with relational aesthetics.

- “Artists in the role of community liaison, which is a role that actually exists at DDC already [the idea of artists filling this role is new], so that it’s not just about telling people when the water is being turned off, but really doing projects that engage people with what’s happening in a community.”

- “Artists could be on design teams from the beginning, making recommendations that might actually get built into the project.”

- “The third idea is to have artists as fellows. They have student fellows at DDC, but having artists as fellows could really make it possible for artists to begin to understand how this agency works. I think many artists, especially younger artists, are interested in socially engaged practices and how they could impact the city.”

Not only have artistic strategies changed since the 1960s, but cities and their approaches to economic development have too. Influential urban theorist Richard Florida’s theory that attracting the “creative class” is key to building thriving cities has shaped urban design and public arts policy not only in the United States but around the world. Recent decades have seen cities aggressively brand themselves, competing with other global cities to be considered ‘world class.’ This has produced waterfront revitalisation projects and showstopper parks. It has also seen a focus on “creative placemaking” as a catalyst for urban regeneration.

In The Future of Public Space, a new book produced by the architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Ben Davis writes, “The signature public arts theory of recent years is ‘creative placemaking,’ formulated for the NEA [National Endowment for the Arts] in a 2010 white paper by Ann Markusen and Anne Gadwa, then adopted across the country with ‘unprecedented speed and coordination.’” Creative placemaking sees public, private and community forces shape the physical and social character of public spaces around arts and cultural activities. Placemaking principles are employed by local councils all over Aotearoa, many of whom feature their own placemaking teams. Palmerston North even has a Facebook page dedicated to its placemaking efforts. The featured projects are fairly typical of placemaking initiatives: urban design changes overlaid with public art and programmes to ‘activate’ the spaces.

Creative placemaking also risks subsuming the work of artists, overlooking its critical functions and co-opting artists to gild a city’s national and international brand

The arts are often subsumed under the general umbrella of the creative industries, both in Aotearoa and internationally. ‘Creative colleges,’ which bring together design and fine art schools at the tertiary level are one example of how this is structurally embedded. I have written before of how in Wellington this can be to the detriment of the arts. As the city seeks to brand itself as the ‘creative capital’ of Aotearoa, public galleries and artists are forced to compete with flashier creative industries like film for investment, coverage and even exhibition space. Creative placemaking also risks subsuming the work of artists, overlooking its critical functions and co-opting artists to gild a city’s national and international brand.

Artistic outcomes are distinct from placemaking outcomes, and might seek to serve a different conception of ‘the public.’ Ann Markusen has said that “arts and cultural outcomes are often underplayed in the rhetoric about expectations” in favour of “creating jobs or increasing property values or home ownership.”

When is art no longer art, and when are artists no longer artists?

Sometimes it seems that in public processes the work of artists is conflated with that of designers. The PAIR programme is based on the idea that that “artists are creative problem-solvers. They are able to create long-term and lasting impact by working collaboratively and in open-ended processes to build community bonds, open channels for two-way dialogue, and reimagine realities to create new possibilities for those who experience and participate in the work.” These expectations overlap significantly with our understanding of what designers do: solve problems through a collaborative process of dialogue, research and imagination. When is art no longer art, and when are artists no longer artists?

Christchurch artist Julia Morison has publicly commented that art in the city has increasingly been expected to meet urban design goals – a demand at odds with the freedom that distinguishes the work of contemporary artists from that of designers. The co-option of artists into productive ‘feel-good’ narratives in a ‘transitional’ era of urban uncertainty has also been critiqued by Chloe Geoghegan and Ella Sutherland, who founded the artist-run space Dog Park in the years following the earthquakes. They point out that while they were criticised for failing to plug into the dominant idea of the creative post-quake city (as exemplified by initiatives like Gap Filler), they sought to maintain the integrity of contemporary art’s critical functions: “While the ‘transitional city’ may have made sense for those selling it – the perfect case study for academic and professional pursuits – we wanted to create a reality governed by critical production.”

In her well-known 2006 essay “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” art historian and critic Claire Bishop argues that, in their attempts to shape collegial spaces for connectivity and social togetherness, seminal artists working in a relational mode, such as Rirkrit Tiravanija, are politically ineffective. Bishop evaluates these works using Chantal Mouffe’s theory of agonism, which holds that rather than seeking consensus, a radical democracy seeks to embrace – not eliminate – difference, this tension being a productive political force.

This is an interesting framework to apply to the design of public space, or any process in which an artist is employed to service a ‘public’. I have heard Quilian Riano, an urban designer and researcher working in New York, apply Mouffe’s agonism to New York City’s public spaces. In theory, this is one of the ideals that shapes the publicly funded contemporary art gallery – which might style itself as ‘a safe space for unsafe ideas’ – a space for differences to co-exist and be expressed, anchored by an underlying respect and care for the ‘other,’ who alongside the ‘self’ constitutes the ‘public.’

Motivated by an ethics of care, artists are often striving for a grander conception of ‘public good’ than a single project might allow

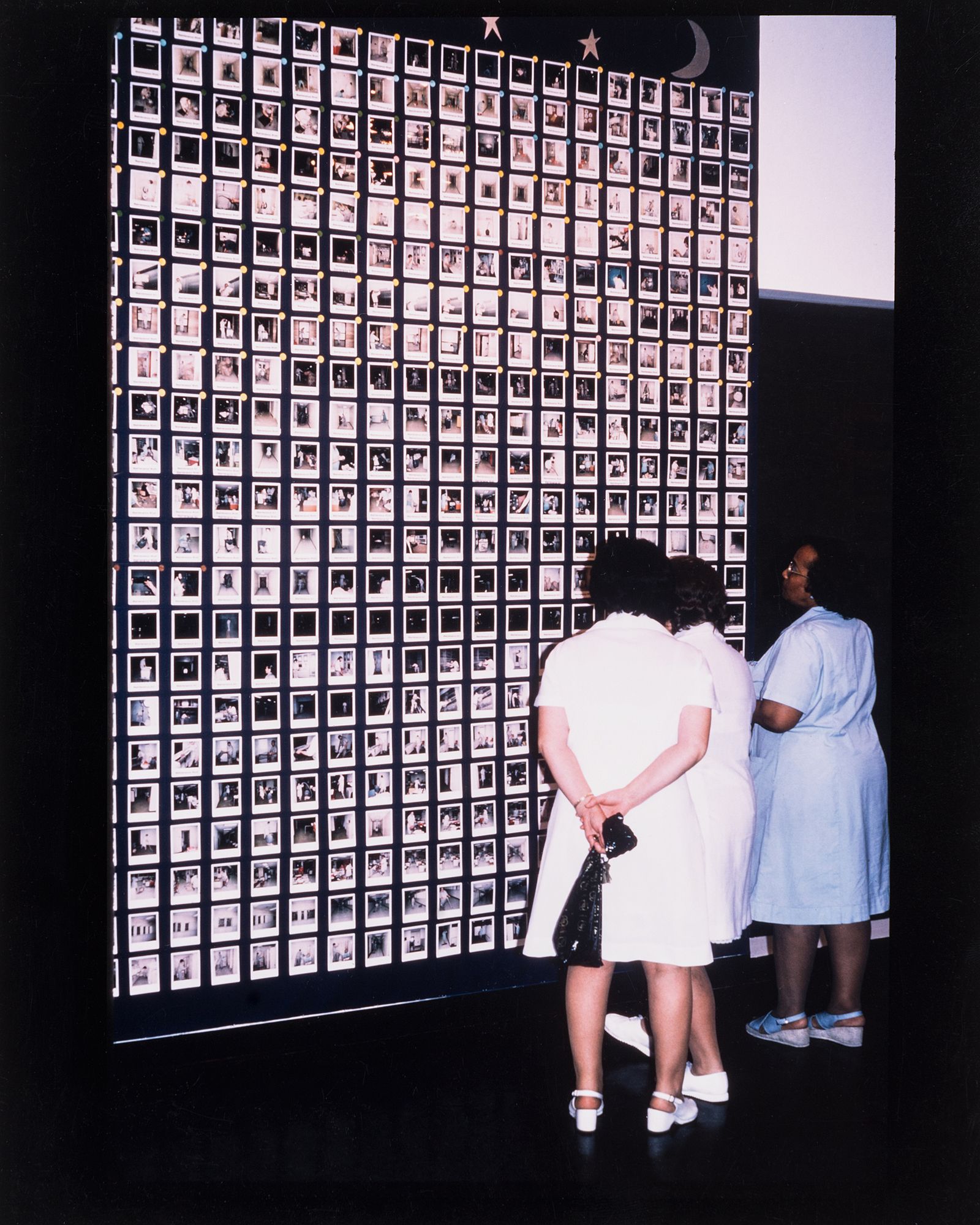

Imagine if Bronwyn Holloway-Smith’s proposed public artworks had been realised. In their site-specific locations they would have advocated for public interests that rub up against governing digital powers – agonism in practice. Similarly, Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ practice is a critical one, born of care for the public realm. As an artist, she uses her position within the Sanitation Department to celebrate the underappreciated workers that sustain the city, and to suggest that New York’s labour issues are philosophical and paradigmatic, not merely practical. The independence she has been granted at the Department of Sanitation was apparent in her career retrospective at the Queens Museum last year, which highlighted a singular and enduring artistic vision. Included in the exhibition was the most well-known work to emerge from her residency, Touch Sanitation Performance (1979-80). The performance saw Ukeles spend 11 months attempting to personally thank each and every one of New York City’s 8500 sanitation workers. Documented in photographs, Ukeles would shake hands with each worker and thank them for “keeping New York City alive.”

Motivated by an ethics of care, artists are often striving for a grander conception of ‘public good’ than a single project might allow. This is the critical function of art, and it is dependent upon the artist’s freedom to act as a critic. But unlike Bishop, I don’t think this means artists must always work in an antagonistic mode. Artists can indeed be valuable facilitators working within public agencies, if what they are facilitating is an agonistic framework for a public that contains multitudes. The role of artists in public projects should be generative, rather than ameliorative.

‘Public good’ is an idea that is constantly shifting. A creative city is one that invites artists to contribute to shaping physical manifestations of public good within the built environment. But a creative city that truly values artists also understands that they are not journeymen, and is willing to support them even when they can’t be put to work in the same way as other creatives. Sometimes artists are the big cogs, working on slower, more fundamental change.