The Brooding Elitist Relationship-Wrecker: Tropes of Art and Artists on Narrative Television

How do stereotypes of art and artists as seen on television influence popular opinion? Zita Joyce explains.

How do stereotypes of art and artists as seen on television influence popular opinion? Zita Joyce explains.

New Zealand media and politicians have long had an uneasy relationship with art paid for by public money. Paul Holmes' attack on the 2005 Venice Biennale representative et al. and the 'braying dunny' was one of the more defining moments in public art criticism in recent decades.

Roger Horrocks' analysis of that incident, published on The Pantograph Punch in May 2016 identifies several key tropes in the representation of artists and art, referencing Jim and Mary Barr's 1987 book, When Art Hits the Headlines: A Survey of Controversial Art in New Zealand. These are based on the 'common sense' attitude that, "difficult art is a kind of confidence trick, and art experts are intellectual bullies who try to intimidate those who can see through the racket." Playful or ironic art is, "further proof that artists are sneering at the public." The media and political coverage he cites through the second half of 2004 refers to artists and the 'arts fraternity' as elitists who look down on ordinary New Zealanders, while bludging money from the state/taxpayer.

et al.'s refusal to speak to the media about the Venice Biennale further incensed media figures like Holmes and Micheal Laws. This was used as evidence that this difficult artwork and artist were self-indulgent and undeserving of taxpayers’ money as an international cultural ambassador of New Zealand.

et al.'s refusal to speak to the media about the Venice Biennale further incensed media figures like Holmes and Micheal Laws. This was used as evidence that this difficult artwork and artist were self-indulgent and undeserving of taxpayers’ money as an international cultural ambassador of New Zealand.

These kinds of debates reflect what media commentators and politicians think will be popular positions, as two professions that are finely attuned to what 'the people' think. The fact that New Zealand did not send an official representative to the following Venice Biennale in 2007 is a clear example of media representation influencing future decisions about art and public money.

Holmes, Laws, and the other commentators who weighed in on the value of taxpayer-funded art in 2004, in the lead-up to the 2005 Biennale, were playing to a particular audience, and as Horrocks suggests, may have been consciously playing particular roles in order to encourage or respond to the 'debate'. Representation of the art and artist were therefore at the service of a populist position within a grander media narrative.

This kind of populist position that frames artists as 'self-indulgent' and 'undeserving of taxpayers’ money' is not just evident in news media coverage of specific art world incidents but also in narrative television. On television, representations of art and artists have to serve the genre and longer term narrative goals of a series. Many television representations of art and artists are consistent with the populist discourse Horrocks identifies. However, there is also scope for the sustained structure of long form narrative television to open up complex representations and enable audience identification with characters and storylines related to art - difficult or otherwise.

*

There are many ideas about how audiences understand media, considering audiences as passive receivers through the ‘hypodermic needle’ of ‘media effects’ theory and as active ‘Produsers' who participate in and produce as well as consuming media content. ‘Active Audience’ theories focus on audience interpretation of media content, proposing that as audience members we understand media from our own social context. This means that our interpretation of television programmes is grounded in things like our gender identity, ethnicity, cultural background and identification, language, social position, education, habits, interests, prior knowledge, and the attitudes of the people around us. The cultural tools we bring to that interpretation are not uniform, which means we don't all interpret television programmes in the same way, because we don't have the same interpretive resources.

When it comes to representations of art, artists, and the art world more broadly in media, some audience members will bring real-world cultural knowledge to their interpretation. This means appreciating or critiquing on-screen representations of art, artists, dealers and collectors in relation to lived experiences. However, other audience members will have fewer personal art-related reference points to draw on, so the representations seen on screen may be more influential in shaping their understanding of art, artists, dealers and collectors .

*

Johanna King-Slutzky has documented numerous examples of art in narrative television, with a particular focus on crime programmes. Shows like Law and Order: SVU and Bones rely on bad fake art, where the artist characters who created it have to over-explain their work to make up for its failures. And as King-Slutzky comments, "because his or her work is plainly boring, script writers have to make the artist into a self-important lunatic in order to caulk the cognitive dissonance. This only amplifies the boring art/windbag artist trope for future TV shows." This bad art is often created by prop departments specifically to make a point about the vacuousness of art itself, and there is an entire industry for renting out prop art for television.

In most television programmes, abstract expressionism, "still pisses us off, artists are tortured, PoMo is meaningless, the art world is for criminals and love bandits, everyone wants to get laid, and the shows you actually have to pay for have more realistic art."

The ‘badness’ of the art on television is often used to characterise the artist as well, with particular forms of art providing commentary on both artists and audiences. King-Slutzky points out that abstract expressionism, for example, is favoured by "murderers and adulterers", and 'ab ex' paintings are, "pretentious, illegible — and the artist almost always has ulterior motives". Video artists are jerks, as are performance, installation, and conceptual artists. She notes that most programmes don't treat art seriously, and use art, artists, and the art world in general as an object of derision to highlight characters’ pretentiousness, and the emptiness of art conversations. In most television programmes, abstract expressionism, "still pisses us off, artists are tortured, PoMo is meaningless, the art world is for criminals and love bandits, everyone wants to get laid, and the shows you actually have to pay for have more realistic art."

These broad characterisations hold for many single-episode and one-off representations of art and artists on TV. Artists as continuing characters in narrative television often function to force main characters out of their comfort zones, to open up new possibilities in their lives and relationships. These kinds of characters are often portrayed as 'free spirits’, who don't follow the same norms as others. Most obviously, they tend to live in open warehouse studios instead of normal houses or apartments, and they either cannot maintain a stable relationship, or pose a threat to others' relationships.

At the extreme end of this scale is Lila West, Dexter's addiction sponsor in season two. She is an installation artist who lives in a large industrial warehouse studio and not only causes Dexter's girlfriend Rita to dump him, but kidnaps Rita's children, and turns out to be a murderer and pyromaniac. Booth Jonathan in Girls is similarly self-obsessed, and one of many examples of an artist whose role is to initiate a sexual interaction that pushes a main character from her comfort zone, including trapping her in an actual video installation booth in his studio. He offers art world credibility and sexual adventure, but not a relationship. Adam Galloway, the photographer with whom Claire Underwood has a long-lasting affair in House of Cards, is far more sane, but his warehouse studio represents a kind of relaxed freedom that is everything Claire's marriage, power-strategy, and home is not.

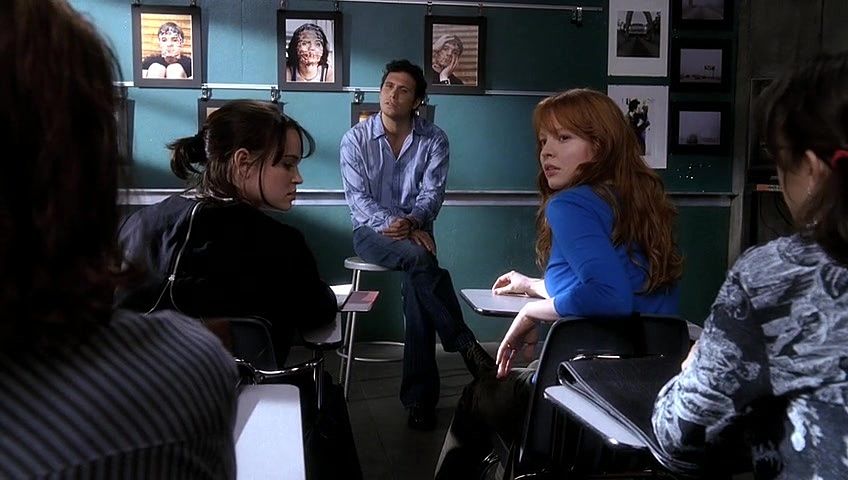

Artists who are main characters in the narrative are able to develop deeper interconnections with others, if not stable romantic relationships of their own. They also tend to be nicer and have more complex story arcs. Felix in Orphan Black's grungy industrial painter's loft both counterbalances Alison Hendrix's perfect suburban soccer mom home, and serves as a sanctuary for the other characters. Claire Fisher in Six Feet Under is a rare example of a character whose development as an artist is central to her role in the programme, and her experiments with relationships. Six Feet Under traces her art practice from high school to art school and beyond, in an extended televisual study of artist development. Her time at the fictional LAC-Arts is a realistic representation of the student experience in many ways, but also falls into the tropes of, as Carol Kino argued in the New York Times, “the art teacher as a melodramatic twit”. Still, as a programme that takes art practice seriously, it is possible to identify relationships between Claire's portraiture and the narrative, and it's notable that Claire's most successful work at LAC Arts was borrowed directly from artist David Meanix.

Some programmes have main characters who have an art practice yet don't necessarily become artists themselves. Perhaps this is most evident in the character of Pam/Dawn in the US and UK versions of The Office. Both of them are receptionists who really want to be children's book illustrators, but bury their inner artist in more normal lives. The choice between an artist's life and a 'normal' life is more open for teenaged characters, like Claire Fisher and also Matt in Friday Night Lights and Joey in Dawson's Creek, who are 'good at drawing', and use it to express their feelings for others. While Claire was never 'normal' to start with, thanks to living in a funeral home in Los Angeles and driving a hearse, Matt and Joey are stuck in the narrowed possibilities of small town normality. Joey's art practice is subordinate in the narrative to Dawson's filmmaking dreams, but Matt's story explores the consciously divergent character options of staying in small town Texas tied to family and football, or taking up a place at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Some artists push beyond the boundaries of time, as visionaries who are lifted out of the ordinary world inhabited by the other characters. Isaac Mendes in Heroes and Pauline Verdreaux-Rennie in Under the Dome drive the narratives by painting the future, leaving clues for main characters to interpret. An artist may also seed clues in more mundane ways, by taking a photograph, for example, at a serendipitous time, as Jonathan Byers does in Stranger Things.

Leslie Knope and the Spirit of Pawnee: Parks and Recreation Season 5 Episode 10 “Two Parties”.

These visionary artist characters often generate more attention for their actual art than other artists, inspiring close readings by those seeking to understand the truth hidden in the work. All of these characters draw the series' protagonists in with a combination of their art and also a personality or lifestyle that diverges from the norms of the show. In a tangential sense, the civic art of Pawnee Indiana, the populist paintings of the town's racist past, plays a central role in the narrative of Parks and Recreation, when close analysis reveals the deep roots of contemporary attitudes and issues.

A more normal engagement with art is for a main character to work in a gallery, although this is usually a possibility only for beautiful women in New York. Joyce Summers is a significant gallerist exception, as a mother based in Sunnydale California, but her gallery is never seen in Buffy, and its primary presence in the narrative was as a source of dangerous objects of demonic possession. As epitomised by Charlotte in Sex and the City and Marnie in Girls, the gallerist is a glamorous job in its own right, but also mediates between other characters and the art world. Rufus Humphrey was obviously not a beautiful young woman when he opened his gallery in Gossip Girl, but Vanessa Abrams filled that role on his behalf. As the least wealthy/most Brooklyn-based characters in the show the art gallery positioned them perfectly between the art collections displayed so prominently on the walls of the Upper West Side Elite and the 'bohemian' artists of Brooklyn's gentrification.

Marnie hands-on in the gallery: Girls Season 3 Episode 11 “I Saw You”.

When the gallerist is a less central character, their role as mediator between artist and art buyer is often more apparent. Vanessa Mariana's connection with Daredevil 's Wilson Fisk in her gallery Scene Contempo is introduced by the painting Rabbit in a Snowstorm, which is used to illustrate both Fisk's wealth and his tortured human awkwardness. In this, Fisk epitomises the long line of criminal characters drawn to modern and abstract expressionist art that King-Slutzky identifies as one of the signifiers of the truly successful wealthy bad guy, so much so that he collects the gallerist as well as the painting.

*

Art in a gallery setting functions as a background for characters, and as an object to be displayed, discussed or derided by others. However, art in homes and offices tends to primarily signify wealth and taste. The most significant collections on set tend to be in NewYork-based programmes. In Mad Men, real abstract minimalist art, and 'fake' art set design signifies modernity and money, and generates conversations about changing aesthetics. When Bert Cooper buys a Mark Rothko painting for his office, the other characters cannot decide what to think of it, whether it is a joke, $10,000 emperor's new clothes-type 'smudgy squares', or a work of art so meaningful it is impossible to understand. Ken Cosgrove suggests maybe it doesn't mean anything, "maybe you're just supposed to experience it. Because when you look at it you do feel something, right? It's like looking into something very deep. You fall in." Pressed for a perspective on it, Cooper himself explains "People buy things to realise their aspirations, that's the foundation of our business. But between you and me and the lamppost that thing should double in value by next Christmas." The Rothko is interpreted from a set of familiar tropes: not pictorial, therefore not art; art because it offers an experience; an object of aspiration; and a straightforward financial investment.

Contemporary art is treated as a more straightforward decor of the wealthy in Gossip Girl and Empire, both of which notably feature real paintings. The paintings in Gossip Girl were provided by Art Production Fund, a non-profit organisation that used the programme to reach new audiences for contemporary art. The most prominent artworks included the Richard Phillips pop art paintings above Chuck Bass's bed and on the van der Woodsen's stair case, and Elmgreen and Dragset's Prada Marfa sign in the van der Woodsen's entrance. That one is particularly symbolic, referencing another Art Production Fund project in the original Prada Marfa installation, which critiques the gentrification of artist areas of New York, and conflates the conspicuous consumption of art and designer clothing, all of which neatly summarises the surface layer of Gossip Girl itself.

Empire even earns a discussion on Larry's List, "the leading art market knowledge company providing insights, data, and access to contemporary art collectors" for the quality of its art, as contemporary African American artists like Kehindra Wiley, Mickelane Thomas and Jamea Richmond Edwards feature alongside the classics, like Basquiat, Monet, Surat, and van Gogh. The show still perpetuates familiar characterisations of the artist as an unhinged relationship wrecker when Michael cheats on Jamal with the painter Chase One. Given the overwhelming whiteness of television representations of artists themselves, including Chase One, Empire’s work in supporting and representing African, and African American, artists is at least as significant as its representation of musical culture. Even more than Gossip Girl, Empire acts as a televisual art gallery, bringing contemporary art to screens far away from the major institutions.

There is little documentation of artist representations on New Zealand television, although there is certainly art on walls in local programmes. The sets of Gloss displayed work by Elam students of the 1980s, and a guide to recreating 'the look' of Chris Warner's home in Shortland Street includes paintings by Jonathon Brown and Hope Gibbons, and a sculpture by Marte Szirmay. Artist characters in Shortland Street have illustrated some now-familiar tropes. Julian Pound, for example, is described in plot summaries from 2014 as "mysterious, unnerving", "dark, controlling", and having "brooding intensity", and an "edgy, brooding charm". He was clearly no good for Dayna, whom he ensnared and manipulated, pushing her to a literal edge in the name of art.

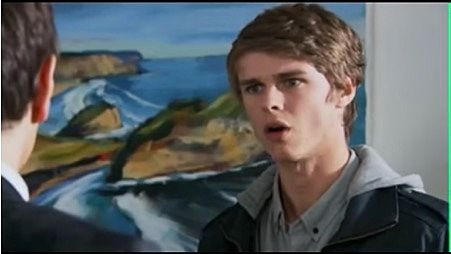

In contrast, Phoenix Raynor, Chris Warner's surprise son, was just an idealist kid struggling, in the words of his final bio: "with how to turn his passion for art into a career." This is illustrated in a scene that painter Sam Mathers has archived on his website, documenting the appearance of his painting Mission Bay, the Promenade.

Phoenix Raynor protests the value of art: Shortland Street Series 22, Episode 5310.

Chris brings Phoenix to a dealer gallery for a private tour by the gallerist and critic Simon Sweeny. While Phoenix seems amazed by the number of local paintings, Chris and Simon discuss the state of the art market and the value of the paintings, against which Phoenix protests that, "Good art should be available to everyone. Not just businessmen and doctors with cash", hung in mansions where it won't be seen. Against Chris's protests, Sweeny remarks, "He'll probably find it more tolerable when he starts getting paid commissions," and "It's this kind of fire that makes the best work", before prompting Chris to spend more of his cash on something to fill spare wall space at home.

Where Julian Pound represents the familiar dangerous and manipulative artist character who is convinced of his own worth, Phoenix Raynor is unable to resolve the conflict between art practice as self-expression and Chris's understanding of art as an expression of wealth. In the contrasting mode of regular people who have an art practice but are not artists, Van's foray into life drawing in Outrageous Fortune was brief but successful, as the way he met his wife-to-be Elena-the-life-model. His artistic ability is never clear, but this is a rare instance where an accidental encounter with art leads to a successful relationship.

*

Many of the representations of art and artists in narrative television reflect those same characterisations that were exercised so vigorously in the New Zealand media in 2004. Art is seen as 'difficult' and people who talk about it are 'pretentious' in these examples. Artists are seldom main characters, and their lives, relationships, homes, and careers tend to not conform to normal ways of life, including proper housing, jobs, relationships and children.

Artists on television may be creative free spirits, cynical commercial players, idealists, truth-tellers, and brooding manipulators and are almost certainly white, but they are not ‘normal’ people like those addressed by media commentators and politicians. Characters who can draw well but are not 'artists' highlight the distance between normal people and those who are part of the art establishment. And working in a gallery is a wonderful career for beautiful young women in New York, but only in New York, as it is the centre of the art world. As Gossip Girl and Empire show, television can serve as a form of art gallery in itself.

One issue of representation among many, the archetype of the artist is a great example of how narrative television can reinforce stereotypes, an issue which also spans on-screen depictions of ethnicity, gender identity and ability.

Art on television provides access to contemporary art for audiences who may have limited experience of it in real life, but it also locates art in homes of the wealthy, associating it purely with private wealth rather than public good and public money. Narrative television suggests that artists are probably rich already, since rich people buy art, and simply undeserving of public money because they are so weird.

Public discourse around art would probably improve with more realistic and varied artists featuring in narrative television. Interpretive audience theory argues that people understand media through their own experience and context, but this becomes circular when experiences of artists and the art world are derived primarily from television in the first place. One issue of representation among many, the archetype of the artist is a great example of how narrative television can reinforce stereotypes, an issue which also spans on-screen depictions of ethnicity, gender identity and ability.

Many thanks to Jamie Hanton, Director of The Physics Room Contemporary Art Space, Christchurch, and the participants of Seen and Heard: Public Displays and Public Discourses: A critical writing workshop convened by The Physics Room, October 2016. Thanks also to Su Ballard and Adam Willetts.

Further reading about art on TV, and in the movies: