Art in Isolation

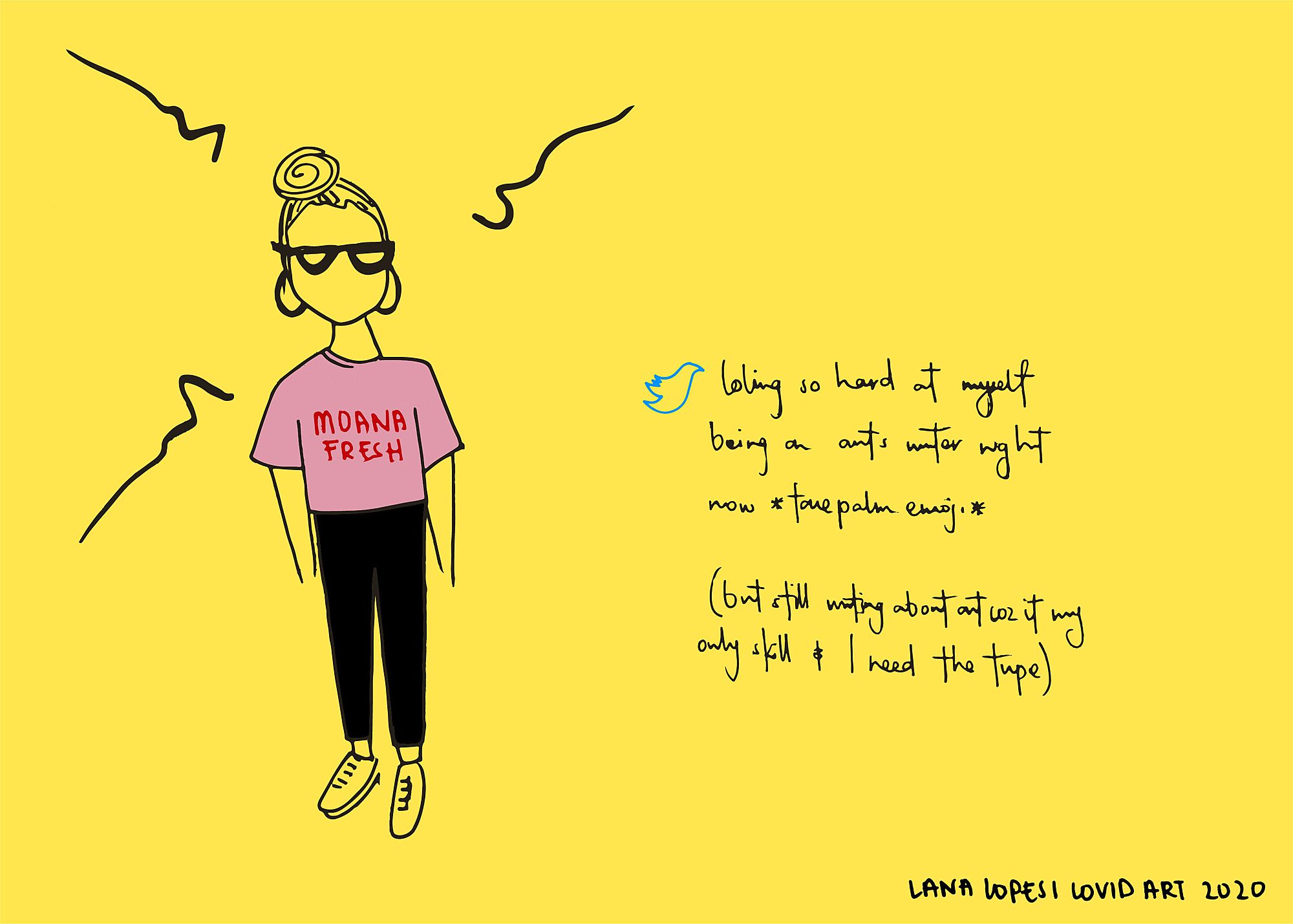

What can an art writer do in a pandemic? A personal essay from Lana Lopesi on the place of the art during Covid-19.

Our arts spaces all have the unique job of connecting the art with the people. They are closing on a massive and global scale. Beyond talk of financial loss, the main topic of conversation seems to be how we can still do the things we’ve always done while simultaneously physically distancing. While physical distancing and self-isolation have undoubtedly changed the way we show art to, and interact with, our audiences, one could argue self-isolation is the prime environment for artists to make art.

Isolation is not a foreign concept to art. If anything, the isolated artist is a well-established romantic trope made famous in the 18th century, and we’ve refused to let go of it since. It sits somewhere alongside the drunk artist, the starving artist and the depressed artist, and the cocktail of all of these supposedly results in creative genius.

The isolated artist trope has been reinforced by artists themselves, notably male painters. People such as Pablo Picasso, who said, “Without great solitude no serious work is possible.” Andy Warhol, who said, “People are always so boring when they band together. You have to be alone to develop all the idiosyncrasies that make a person interesting.” And Robert Genn, who said, “Artists with serious aspirations need to be left alone to follow the course of their own imagination.”

Given this time of forced isolation, this trope is again rising to the surface, with a number of artists looking on the bright side, seeing isolation as an opportunity enabling them to make art when they would otherwise be disrupted by regular life. So for those fortunate enough to have a studio space, I imagine to some degree this offers potential.

*

How luxurious is it to be writing about art now? Why would we need it and who the hell would read it?

March 18, 8:43pm

The Pattern told me today that I “can come across as ungrounded, spacey, or like you don’t want to deal with reality.” Well no shit, Sherlock, have you seen the reality of today? My reality is that we are living through an episode of Black Mirror, and for some good reason I decided to be an arts writer. A fucking arts writer. Like not even an artist – an arts writer.

When the virus was first spreading I traced back where my income comes from (largely Creative New Zealand, other philanthropic donations, advertising money and subscriptions) and thought about how, luckily, the platforms I write for have (most likely) already been given their pots of money for the year and so, to an extent, I will still have work. (Although, what if CNZ takes the all money back? And the print magazines shut down because no one can leave the house to buy the damn things?)

But on the other hand, I cannot bring myself to actually write about art. A 1500-word piece on an installation is really not something I can focus on. Because how luxurious is it to be writing about art now? Why would we need it and who the hell would read it? I feel like I’m frozen in limbo because all the projects I had on the boil don’t really seem to matter. No project really matters.

There’s something about art that distances us from ‘ordinary society’ (we at least like to think we are distanced), almost above things, and in these times we really see that distance because what we do is so unnecessary in terms of our basic survival as human beings.

Being an arts writer now is to realise that your line of work is superfluous. What makes it worse is that if I’m not writing about art, I’m at university writing about imagination and mobility – *facepalm*. MOBILITY!

*

So how do we make art during COVID-19? For some it seems like business as usual. A chance to head into your studio and get on with projects already underway. Maybe for others, forced to take time away from their usual work, it’s a chance to finally bring those ideas to life that they have always thought about.

But the chaotic and ever-changing environment, typified by a sense of panic, might mean that for some artists COVID-19 itself has to be the subject for art making. In a sense it provides ample inspiration for artists interested in science fiction, apocalypse and futurism. For those, such as myself, who are struggling to concentrate on anything other than keeping themselves updated with the changing situation, maybe making art about and responding directly to COVID-19 is what is most interesting at this time.

*

The isolated artist clearly doesn’t have kids (and probably isn’t a woman).

March 19, 10:27pm

Twenty-eight cases as of today. It feels like school closures may be imminent. To be honest I would feel safer and better about the situation if they would just make a call. Because being on edge about it all is pretty unnerving at present. Every day I wonder if I should pack up everything and take it home in case the university closes, or wherever else closes. But then again, having the kids home with me for days on end would also be its own kind of hell.

The isolated artist clearly doesn’t have kids (and probably isn’t a woman).

How on earth would anything happen? I guess it just wouldn’t happen because none of it really matters, right? My art writing seems more like a vanity project than anything else right now. Like not something anyone needs but something to keep my own mind sane, to keep the panic attacks at bay. Sometime I wonder whether I’m experiencing the COVID-19 shortness of breath or a panic attack – so far it’s only been panic.

But also I need to write. As someone who has decided that this is what I am going to spend my time doing, I feel that urgency to write, to put words on a page and fix them so that I can fix some of the thoughts swirling and crashing upon themselves within my head.

*

I think what we have to be cautious of as communities of makers in this time is to not reify the isolated-artist trope. Because, as mentioned earlier, what go hand in hand with the isolated artist are mental-health issues and substance abuse. In a recent article, Kate Montgomery – who suffers from a chronic auto-immune disease and is well qualified to talk about self-isolation – writes that exercise, fresh air and laughter are vital for surviving self-isolation.

While the isolated artists might be able to make the art, what then?

And while we perpetuate the idea of the isolated artist, art really is a social game. On the one hand it makes the spaces in which we show art vital, whether it’s time spent interacting at an opening, talking to a curator while seeing an exhibition or just catching up with your arts community, those all happen in our gallery spaces. Community also comes together by visiting an artist’s studio as well as the parties, drink-ups and pot-luck dinners. It is here that opportunities can arise, collaborations start and the ideas for new artworks can be birthed. As Albert Einstein famously said, “Creativity is contagious, pass it on.” So while the isolated artists might be able to make the art, what then?

*

March 20, 9:32am

So I’ve taken to writing about COVID-19. This is my third piece on it. I was hoping that, by now, three pieces in, I would have found the cathartic release I was looking for, but I haven’t. I just feel like I’ve added to the masses of data already pinging around online.

The speed of this moment seems unreal, I have never had pieces I’m working on outdate within an hour. With so many people in isolation, what does go up gets consumed so fast and then we’re onto the next death-toll update, border closure or economic package.

I’ve been staying up late to get writing done, which also means I’ve been stress-eating chocolate, drinking Red Bull and buying pies at the bakery across the road because, you know, small business stimulation, doing my part, etc, etc.

What is my role here? And how does this fit in with the other things I think I should be doing as a socially conscious person. Maybe locking myself (and my family) in a small house is being socially conscious. And maybe making sense of my thoughts by writing through them in a Word document instead of adding to the chaos on social media is me being socially reasonable.

I don’t even know what I’m talking about.

*

The obvious answer is to go online. And people are quickly trying to work out how to make the online work for us. Universities are teaching online, we can have Netflix parties, Art Basel Hong Kong has moved to online viewing rooms and Wellington author Damien Wilkins just launched his new book, Aspiring, online. In addition, the BBC has launched Culture in Quarantine with the aim of being “a stage, gallery and cultural platform in everybody’s homes”, Social Distancing Festival brings together global livestreams, and Wellington’s BATS theatre has trialled a pay-to-play livestream performance of Friday’s show Princess Boy Wonder.

Undoubtedly we will continue to see what these online arts spaces might look like.

Online as a site of artists’ community-building and collaboration is fairly well established. Before the social media sites we know today, net art communities of the 90s offered artists places to share what was happening, discuss works and shows and, well, share works. On what we would know now as the prehistoric internet, in 1991 German artist Wolfgang Staehle set up The Thing as bulletin-board system about art, still accessible here. The Thing was followed by similar sites GeoCities, 1994; Rhizome, 1996; and DeviantArt, 2000.

In a great article called ‘The Rise and Fall of Internet Art Communities’, Kelsey Ables writes, “The first type of art made on computers was art made for computers, and in the 2000s, the more customized desktop, the better.” And I would suggest that COVID-19 is going to bring about the next ‘turn’ in internet art (post-post-internet?). Ables concludes her article, “Some relics and rituals of the early internet are probably better left dead – the acronym ‘TTFN’, the dial-up modem tune, the wait for images to load line by line – but the collaborative, creative culture it fostered is bound for a revival.” I’d say the time for that revival is now.

*

While we are physically grounded, I don’t know if we’ve ever been more virtually mobile.

March 21

Have ya’ll been online at the moment?

It is the most active I’ve seen Twitter ever. I mean I’m glad I’m off Facebook because I think being on all platforms now would just be a bit hectic. But it’s so intense. Whenever I have a lull in my day I think to myself, go on Twitter. I last about four scrolls before I have to close it.

While we are physically grounded, I don’t know if we’ve ever been more virtually mobile. It’s as if New York is the next suburb over and Wuhan across the road. The speed with which we get updates from hospital beds in the UK or people in isolation the world over is insane. How the hell do we keep a sense of perspective in all of this?

I ended up on the Metro magazine website to read an article about how people are horny for Paul Goldsmith. (I had to Google Paul Goldsmith, and, like really people? *Raised eyebrow*.) I ended up reading Metro’s back-catalogue of art stories and it was nice. I’ve been avoiding Twitter and going straight to RNZ and The Spinoff websites for COVID-19 updates. Like actually typing the URL in Google Chrome instead of just following links. Who am I? All those folks that said landing pages are dead, where are you now?

I saw an Instagram story which basically said artists should feel free to nap now too, instead of exacerbating self-isolation as a false ideal for an inner creative genius. Another one was about how self-isolation is turning people into assholes because they’re sharing on social media how productive they’re being, how much high culture they’re either consuming or making.

Meanwhile my three year old is driving their motor truck over my head during a Skype meeting. I’m done, eh.

*

What art tells us about this time? Who knows. What is for sure is that the art made during any time like this is often one of the key archival records that remains. Even if part of that is the fact that, for a while at least, there is no art at all.

All illustrations by Lana Lopesi