Aroha Mai ~ Aroha Atu

Lara Taylor, Kathryn Gale, Alison Greenaway and Desna Whaanga-Schollum reflect on how they created safe space on a recent noho marae wānanga by operating in aroha.

Through collective contemplation about a space the authors created for a recent noho marae wānanga, our piece considers what operating in aroha means. Understanding that our planetary ecosystem is kept in balance through the giving and receiving – the sharing – of breath, energy and wairua, our wānanga about Te Tiriti-led environmental work at Ohaki Pā, Reporoa, in May 2023 became a space of creativity, engagement, healing and care.

When manuhiri step onto a marae, we step into an unknown space. We don’t know what energy, what intentions lie there. However, we step into it with our own intentions and bring with us our energy and wairua. We step into that space by invitation; generally for a shared purpose, some common element brings us all together.

In this piece, we contemplate our roles and obligations when creating or stepping into these spaces. We consider what it means to create a ‘safe space’ for all involved – both manuhiri and haukāinga. How these spaces emerge and evolve, and the intersection of energy and wairua. And whether those spaces are closed – if so, how? Where does that energy go from there?

Operating in aroha tests boundaries and elicits critical thinking about spaces known and unknown, internal and external, physical and metaphysical. We share the thoughts, emotions and intentions that we’ve received; outwards, back, forward, spiralling. These travel on and into whatever new spaces are carved in a process of giving back.

Aroha mai ~ Aroha atu.

Lara (haukāinga): Ko te wahine te whare tangata o te ao Māori. Women are the house of humanity of the Māori world.

In te ao Māori, the womb is referred to as ‘te whare tangata’ or the house of humanity. Women are revered as the holders of this space, integral to the care and wellbeing of all humanity.

The role of wāhine was reflected in many ways at our Ohaki wānanga. Through the co-design, organisation and facilitation led by two wāhine. Through our two kaikaranga, whose voices and wairua reached out across the initial space in between the two groups (manuhiri and haukāinga) and drew us together. Their voices negotiating, settling, and creating a safe space on behalf of us all, as Kathryn shares in her kōrero.

The feminine energy could be known (or felt) in other ways, too. For example, unlike the east and west coasts, which are often associated with binary energies – the east being the gentler, more feminine energy while the west is considered more masculine due to its wild, raw nature – Ohaki Pā is located on the banks of the Waikato Awa. Geographically, it is in the Central North Island of Aotearoa. Emotionally, perhaps, it has a more neutral energy, which may reflect this central positioning between coasts and energies. Furthermore, Ranginui (masculine) can be felt in the awa, balanced and held by Papatūānuku (feminine), whose whenua holds space for the awa to flow through.

Women are revered as the holders of this space, integral to the care and wellbeing of all humanity.

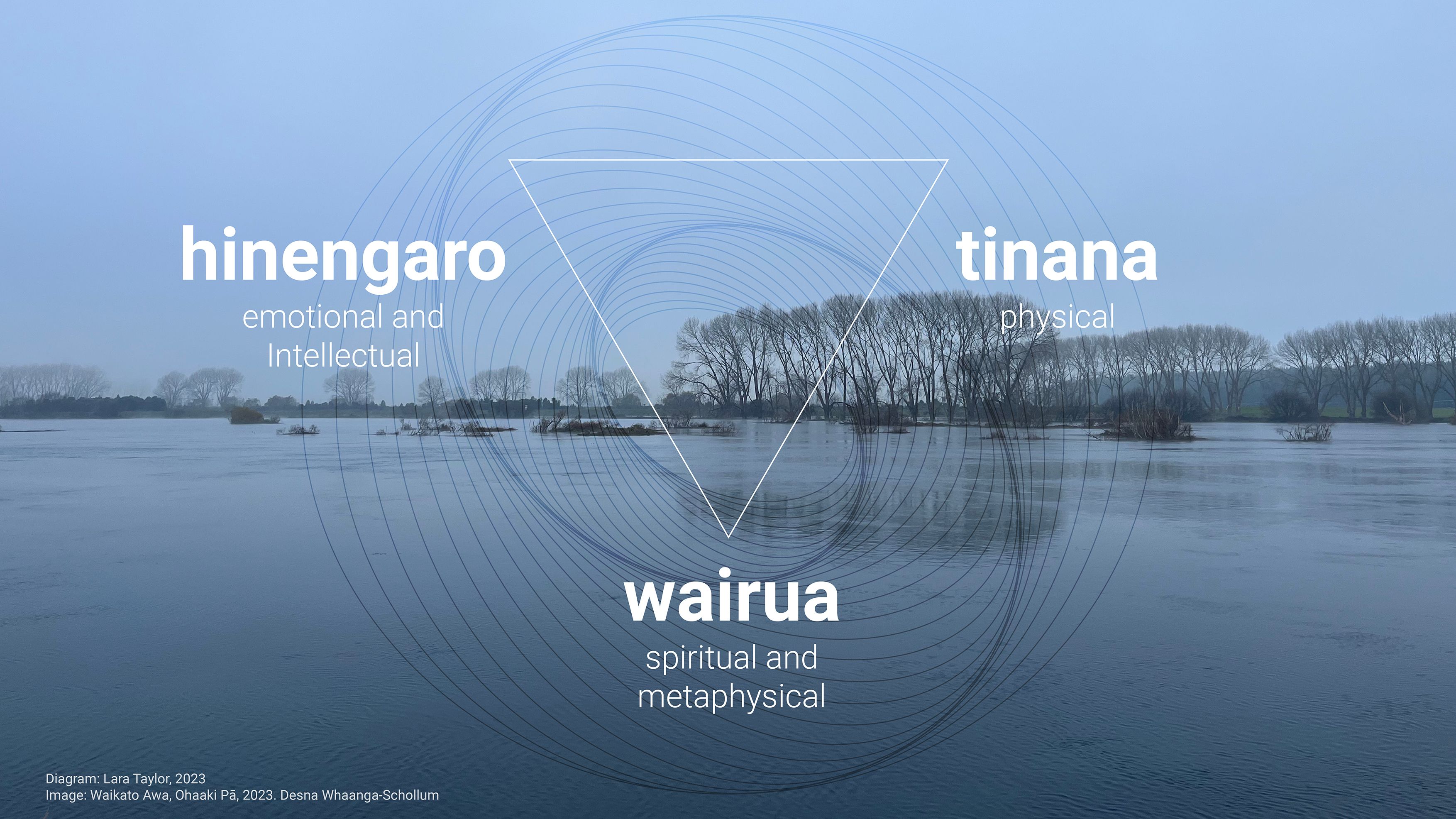

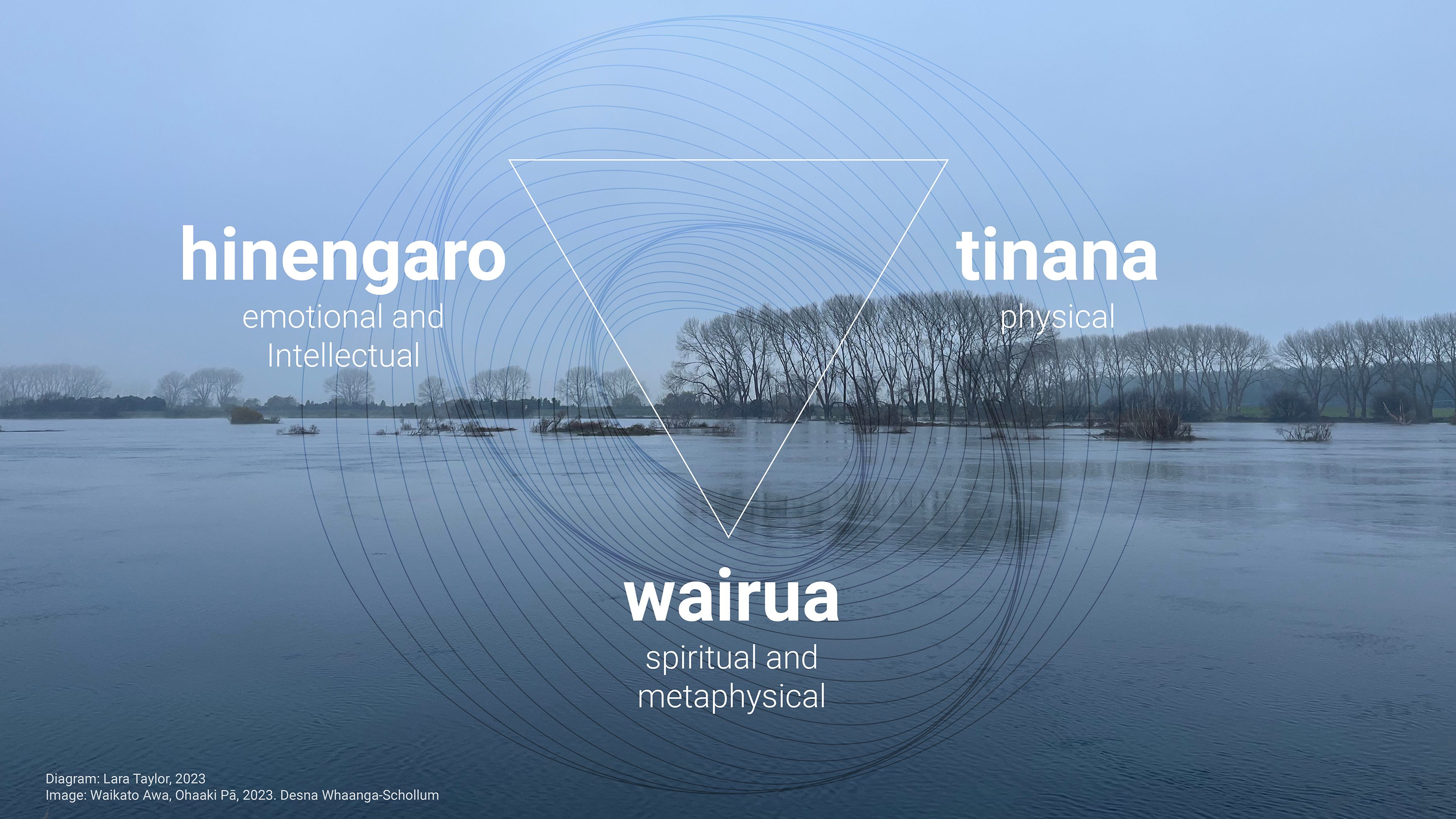

Below, the Whare Tangata is proposed as an alternative to the commonly used model Te Whare Tapa Whā, which was developed by Sir Mason Durie in 1984 and describes health and wellbeing as a wharenui. The Whare Tangata model reclaims and makes space for the role of wāhine. This model was shared with the author through wānanga by two esteemed mana wāhine and important rangatira, Dr Wiki Walker-Hockey (Ngāti Hine) and Lucy Tukua (Ngāti Paoa). Te Whare Tangata Tapa Toru (three sides) is a model that corresponds with the three key elements in Te Whare Tapa Whā: Hinengaro (emotional wellbeing), Tinana (physical wellbeing) and Wairua (metaphysical and spiritual wellbeing). The fourth element of Te Whare Tapa Whā model, Whānau, is unnecessary, because the Whare Tangata, being the house of humanity, reflects potentiality for whānau. In this Tapa Toru model, the focus begins with the individual’s responsibility to take care of themselves (through the three elements), so that they are capable of housing and caring for humanity, and being a responsible and contributing part of a wider ecosystem.

Whare Tangata Tapa Toru reclaims and makes space for the role of wāhine

Tinana | Physical

In relation to our wānanga, we spent substantial time and effort preparing and creating the space physically. For example, drafting a suitable pānui and invitation, setting up an Eventbrite page that could manage and hold space for organising everyone, communications via email outlining important information (like what to bring, and what not to bring – including egos). A series of information about attendees was displayed throughout the wānanga in the whare kai (where we spent a lot of our time talking, thinking, laughing and eating). That information included a list of biographies, and a collation of responses to two key questions that were posed by the organisers pre-wānanga. Time was spent preparing, collating, printing and displaying all of this information – with careful thought around language and framing, and the intention of creating a particular space that was inclusive, informative and encouraging.

Hinengaro | Emotional and intellectual

Interestingly, emotional intelligence is indeed all about energy. ‘Emotion’ is representative of ‘energy in motion’. It was important for us to create spaces that allowed, and even encouraged, all the emotions. Our emotional responses are also related to our physical environment, and the metaphysical (i.e., Tapa Toru). As Alison shares in her kōrero, the harmonising felt through waiata is a combination of all three elements – a physical sound that vibrates the air and space in between, and a ‘feeling’ that is often sensed through our emotional response but is also a metaphysical reaction or energy exchange (that might be felt through our wairua).

Wairua | Spiritual and metaphysical

Wairua is perhaps the most complex element of Tapa Toru to convey through writing. Wairua is integral to operating in aroha, and the energy that is shared and experienced. When individuals are all operating in aroha, the positive energy and intention given out by each person (aroha atu) into the shared space – perhaps a sharing of their own wairua that spirals through the air, shape- shifting all around and between us – again creates an even greater magical, metaphysical energy, which is our collective wairua. This energy is further affected by our mauri, and the mauri of the places and spaces we are in together, or at times on our own. For example, some individuals chose to sit with themselves somewhere quiet, or engage in a healing session with the rongoā, mirimiri and romiromi practitioners who were also present at the wānanga to help nurture this intentional space.

Suffice it to say that ‘space’ is much more than just a physical thing. It is very much an emotional and metaphysical thing as well – and the three elements work together in various ways. We consider the space created through engagement of the three elements (Hinengaro, Tinana and Wairua) as a space of potentiality – one that can be considered and explored within one’s own self. Or it can be scaled up to consider the wider, collective spaces created by combined individuals – such as the pōhiri process and our entrance as one group of (many) manuhiri, or the walking and talking that was done together at Ōrākei Kōrako – the Ūkaipō of Ngāti Tahu Ngāti Whaoa, and again through the ngahere at Ohaki Pā.

When individuals are all operating in aroha, the positive energy and intention given out by each person (aroha atu) into the shared space – perhaps a sharing of their own wairua that spirals through the air, shape- shifting all around and between us – again creates an even greater magical, metaphysical energy, which is our collective wairua.

Though we were moving through physical spaces together, we were also moving through emotional, intellectual and spiritual spaces together. Which takes us back to the start; the creation of spaces where we operate in aroha.

Though never consciously framed this way to the wānanga participants, the engagement of Te Whare Tangata Tapa Toru created an appropriate environment for 60–70 individuals to direct our breath, and intentions, into a collective space of wānanga. One measurement of whether this safe space was achieved was through breathwork – though this is a reflection rather than a conscious strategy used during this wānanga.

In her kōrero to come, Kathryn explains the significance of aro hā. Similar to the use of ‘hā ki roto, hā ki waho’, ‘breathe in, breathe out’ to calm oneself, aro hā can describe directional breathing. When we are uptight, not at ease in our surroundings, our shoulders are up, our breathing is restricted. Whereas if we are relaxed and directing our energy towards the purpose of the wānanga, we are more engaged. There is greater alignment between our hinengaro, tinana and wairua. Breathing is a reciprocal exchange of energy between each other and all living beings – our hā and mauri from our surrounding spaces into ourselves, reciprocated by hā and mauri from within ourselves back out to the ecosystem.

This is operating in aroha – a manifestation of respect, responsibility and reciprocity (among other things). It is not a model that is limited to wāhine, but one often nurtured by wāhine and others connected to a sense of purpose towards care, and towards ensuring the health and wellbeing of humanity.

Aroha mai ~ Aroha atu.

Kathryn (manuhiri, kaikaranga): Creating space, holding space, feeling into and out of spaces

I have a complex relationship with most of the spaces that I exist in. I’m a wahine Māori working in environmental sciences, so I have become accustomed to being the minority, the only, the other, in whatever space I’m in at a given moment in time. I work for a PSGE where I am the only scientist. When I worked at a council I was the only Māori person in the team. It is difficult to find people and spaces that understand my experiences and perspectives, so it is a delight whenever that happens. I think people who are used to being in the majority often don’t have an appreciation for how consistently uncomfortable and subtly draining it is being the ‘other’ all the time. That discomfort makes it difficult to communicate and even to think, because part of my mind is always concentrating on how to be heard by an audience who doesn’t speak the same language as me, how to make sure I am not ‘too’ other and too difficult to understand. It is difficult to flourish and communicate well in circumstances like that.

Wānanga represents a safe space for me, and I think for all people. Wānanga is a space where everyone is expected to be exactly who they are and all of who they are. I’m not expected to compartmentalise my Māoritanga, or being a scientist, or a woman, or any other part of my identity. I didn’t realise until attending this wānanga that I am guarded in so many of the spaces I move in. Arriving at Reporoa, I noticed both a physical and mental relaxing of shoulders and breathing a sigh of relief. In wānanga, being who you are isn’t just accepted, it’s encouraged and appreciated. I have also noticed that I can do better work when I’m comfortable and relaxed. The part of my mind that is usually tied up with translating myself and adjusting my language to the audience is free to use on being creative and saying what I mean the way I feel and think it, and there is a kind of joy in expressing yourself just right. I’m a better tautiaki when I’m in a safe space.

Wānanga is a space where everyone is expected to be exactly who they are and all of who they are.

Operating in aroha

When I find myself in the role of kaikaranga, there are two main values I try to think about and embody: aroha and manaaki.

Aroha comes from aro (to focus) and hā (breath, essence). So to aroha, as a verb, is to focus on, see, appreciate the essence of someone else. Manaaki is similar, it comes from mana (prestige, authority, control, power, status, spiritual power, charisma) and aki (to encourage, urge on). So to manaaki someone is to encourage their own personal power, or empower them, through your actions.

Being a kaikaranga is a big responsibility. You want to acknowledge the essence of everyone in your ope and the individual whakaaro and mauri they bring to the kaupapa, and you want to make a safe space for that to be expressed. For some people, pōwhiri is a scary space. I can remember that feeling, and I try to reassure people that they are looked after here and don’t need to feel afraid. We can’t be empowered to bring the best of ourselves to a kaupapa if we feel unsafe.

So that is what operating in aroha means to me – focusing on the essence of who someone is, and looking for ways I can support them to feel empowered. And one of those ways is by creating a safe space to be.

That’s the whole purpose of a pōwhiri. It’s a process we go through to ensure that different groups of people are safe to come together. Kaikaranga call to each other to share information about who the haukāinga and manuhiri are, to acknowledge each other, and to clear the way spiritually for a connection between the groups to be made. Pōwhiri acknowledges everyone who is present and who they are, and that there may be histories of disagreements between people. But when we choose to pick up the taki, we are deliberately signalling that we are here with good intentions. Everyone who goes through the pōwhiri must share breath during the harirū, must acknowledge and greet everyone from the other group. This creates an environment where everyone can feel seen, welcome and safe to participate in the kaupapa. That aroha is shared.

Aroha mai ~ Aroha atu.

Alison (manuhiri and co-convenor of the wānanga): Writing time and space so that aroha continues to flow

With a pulsing energy radiating from my whole body, as if I have managed to briefly, momentarily hold sunshine, I love, let go and live. Here is a space where we, our ideas and talents are sparkling through the mist and steam. Moist with the potential for new life, and ways of living in this land. Knowing that you are also loving me, thinking of my wellbeing and my perspectives, brings tears to my eyes. I – a Pākehā woman in her 50s who works with the effects of knowledge, in communities struggling with emotional illiteracy, while also often unsure about her own ways of loving – am not practised at just sitting with these feelings. My impulse is to brush them away with a self-deprecating false humility. That day and today I breathe – in, acknowledging the connection, the gift, and out, my enlivened being. Aroha mai ~ Aroha atu, pulsing, arms extended, embracing a turn of phrase which I seem to know while also not knowing. World views carried with me across spaces, vulnerable to storying, possibly connecting, making friends. Ōwairaka, Waikaremoana, Ohāki are extant, their love given and received, time and again. And again here – is it mauri? – spiralling, flying freely, as words once sung in harmony through waiata and now as a pulse on the keyboard.

Aroha mai ~ Aroha atu.

Exploring Orākei Kōrako on the first day of the wānanga. Photo: Early Bird Media

Ōrākei Kōrako. Photo: Early Bird Media

Desna (manuhiri and contributor to the wānanga form): Wānanga – connection and commitment to place and collective space, across geospatial, socio-political and cultural boundaries.

As explored by NathanMatamua, Te Ra Moriarty and Natasha Tassell-Matamua intheir 2023 paper ‘Mai i te Pū ki te Wānanga’, wānanga is a tool for deep thinking that encompasses multidimensional, intergenerational ways of learning and engaging. In symposiums, forums and think-tanks, I’ve been working with creatives, intent on moving beyond industrial mindsets that treat visual language, soundscapes, physical movement, place (takiwā, cultural identity, architecture) and energy (human and non-human) as abstract nice-to-haves, but not fundamentally valuable tools of mātauranga that inform the frameworks within which we think. As the world around us grows increasingly extreme, it is glaringly obvious that the industrialised paradigm is failing people and place – an entity with a specific identity of its own. Kaimahi toi (creative practitioners) are mined for concepts and used as a resource for dynamic energy in the industrial estate, though toi practices are not respected as systems of knowledge. Academia, capitalism and the development regime (the multiple guises of Western ontology) have done their jobs well, to diminish lives into transactional resources.

Mauri wanes, whakapapa and wairua lines become indistinct, song lines stutter towards silence.

Re-energising our whakapapa and mauri

Te ao Māori is grounded in the concept of whakapapa. Whakapapa is commonly translated as ‘genealogy’, but can be understood as a knowledge framework that describes people, Place and practices through a layered relational matrix. Tikanga is informed by whakapapa and underpins various roles, processes and practices. Historically, Whare Wānanga were schools of learning where highly valued oral traditions, lore and mauri were preserved. This knowledge was passed on to rangatira who were considered to be able to hold responsibility for that mātauranga. As with other concepts in Māori society, researchers and practitioners have reinterpreted the term ‘wānanga’ for new applications within the contemporary context.

Wānanga offer an opportunity to connect with, nourish and heal people and Place, and to gather a kupenga (network) of skilled practitioners and their tools to apply to collaborative kaupapa.The format of wānanga provides a conscious platform for cross-cultural discussion, which comes from Te ao Māori understandings of people and place, in Aotearoa. Tangata whenua have a unique sense of belonging – tūrangawaewae is the place where one has the right to stand, the place where one has rights of residence and belonging through kinship and whakapapa. A space or forum for immersive learning, a meeting of people conceptualised as a wānanga, is an event based on tikanga. Roles and ancestral practices form a tapu container which guides and holds the physical and metaphysical space. Care and attention are invested in whakapapa (people, place and layered knowledge), whakawhanaungatanga (relationship-building), kaiārahi (facilitation) and kai (nourishment), to support focus on the kaupapa for which understanding is sought. In the words of Matamua, Moriarty and Tassell-Matamua:

These connections bind humans to the environment in ways that activate naturally inherent processes (e.g., intrinsic feelings, intuition, sense of knowing) that enable meaning and understanding to be inferred between events, actions and intent.

Wānanga – multidimensional, experiential, ways of being, knowing, and doing.

Our whānau of practitioners have had some fantastic times, and some really challenging times, in trying to move this work off the ‘stage’ and/or out of the paradigm of bookended 'traditional ceremonies' clipped on to either end of ‘the real work’. I’m not a movement or sound practitioner myself, and I only hold some small skills in tikanga, our ancestral protocols that are responsive and evolve over time. Relational protocols of engagement, forms of learning, ways of healing; karanga, taonga puoro, the poetics of pūrākau, whaikōrero and many forms of waiata. I understand the forms through the mind of a curious teina, and see immense potential, which could be given space to be fully realised more often.

I’m more hesitant than I should be to weave our wānanga tools into my professional practice, impeded and constantly challenged by dominant coloniser theories of monocultural intellectualism and systemic positivism. Though it seems to be changing – through persistent incrementalism – more often than not, it’s an insurmountable leap of faith for workplaces to respectfully integrate holistic mātauranga.

In Metaphors We Live By, George Lakoff and Mark Johnson argue that our concepts of life do not just govern our thoughts, but dictate how we live our lives.

Our concepts structure what we perceive, how we get around in the world, and how we relate to other people. Our conceptual system thus plays a central role in defining our everyday realities. If we are right in suggesting our conceptual system is largely metaphorical, then the way we think, what we experience, and what we do every day is very much a matter of metaphor.

I respect and value kaikaranga, kaikōrero, rongoā and taonga puoro artists, learning from the woven mātauranga that draws upon expanded bodily sensory sites such as ngākau-centred (heart-centred) and whatumanawa (the inner-eye). Through these tools of kaitiakitanga, we acknowledge our relationships and demonstrate respect and empathy for the ways in which people, and place ‘show up’ in kaupapa. Potential past or current trauma, ancestors' past, present and future, are acknowledged and inform a contextually specific response to kaupapa, guided by ethics of care.

Aroha mai ~ Aroha atu.

Works cited:

Johnson, Mark, and George Lakoff. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago University Press, 1980, 9.

Latulippe, Nicole, Biddy Livesey, Desna Whaanga-Schollum, Cathie Jamieson, Jym Clark, and Rebecca Kiddle. ‘Maanjiwe Nendamowinan (The Gathering of Minds): Connecting Indigenous Placemakers and Caring for Place Through Co-creative Research with the Toronto Islands.’ EPF: Philosophy, Theory, Models, Methods and Practice 2, no. 1–2 (2023): 96–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/26349825231163152

Matamua, Nathan, Te Ra Moriarty, and Natasha Tassell-Matamua. ‘Mai i te Pū ki te Wānanga: Interpreting Synchronistic Meaning Through a Wānanga Methodology.’ Knowledge Cultures 11, no. 1 (2023): 84–97. https://doi.org/10.22381/kc11120235