Threads of Inheritance: Areez Katki at Malcolm Smith Gallery

Every textile tells a story, and the embroidered cloths in Bildungsroman reframe queer and Parsi history.

Every textile tells a story, but the embroidered cloths in Bildungsroman retell and reframe histories.

My first brush with traditional Parsi embroidery came a couple of years ago through a garment in the textile collection of Auckland Museum. Originally catalogued as a ‘blouse,’ it was constructed from a flat piece of wine-red silk, folded and sewn at the side seams. Onto this simple form the maker had embroidered a lush pattern of flowers, birds and insects – so dense that at first glance it appeared to be printed cloth. It seemed to me to have no clear cultural origin, the embroidery style resembling that of a Chinese court robe, but with the sort of notched neckline commonly seen on a kurta (a type of Indian upper garment). As I was to learn, this single garment – known as a jhabla – is a record of the Parsi diaspora. It speaks of their Zoroastrian faith, conceived in Persia but carefully carried wherever the Parsi made their home. It speaks also of their famed success in international trade and enterprise, and of Mumbai and Gujarat, the historic hubs of the Parsi community. In Bildungsroman, recently exhibited at the Malcolm Smith Gallery in Howick, Auckland-based Parsi artist Areez Katki uses embroidered cloth to tell two intertwined histories, tracing the roots of Zoroastrianism to their source, whilst examining his relationship to this inherently patriarchal religion.

Howick, a suburb enamoured of its thoroughly colonial history, may seem an odd choice of location for this exploration of themes. However, East Auckland houses the majority of the approximately 2000 Parsi New Zealanders, including Katki’s family. Only a tiny fraction of our population follows the ancient monotheistic Parsi religion of Zoroastrianism. Yet it is not merely numbers that makes them inconspicuous: assimilation has been woven into the fabric of their community since its inception. Katki alludes to this in one of the first works in Bildungsroman: a sudreh (fine cotton undergarment) delicately embroidered with a cream-on-cream repeating motif of jugs and bowls. The subject is taken from a story which Katki recounts in his journal entries accompanying the show, and which figures prominently in Parsi lore. It is said that Parsis fleeing religious persecution in Persia went to Gujarat, where they convinced the ruler that they would blend into the Indian way of life as imperceptibly as sugar sweetens milk. This need to blend in has made the community wary of sharing their culture with non-Parsis. There is no better illustration of this caution than the text that served as one of Katki’s key resources, an 8kg copy of The Zoroastrian Tapestry, which was printed in an edition of 2000 and only sold to Parsi families. It is this wariness of outsiders that Katki seeks to gently disrupt through his private reinterpretation of Parsi history.

As I wandered through the museum over the past three hours, I began to grasp the monumental scale of this nation’s textile history. It ran deep and spread wide, far beyond the borders of modern-day Iran.

– Journal Extract v, Friday 7th September 2018

This body of work was conceived during a nine-month pilgrimage to India in which Katki returned to sites from his childhood and travelled anew to places of significance to the Zoroastrian faith, becoming the first person in his family to visit all nine Atarsh Behrams (consecrated fire temples). It was also a research trip, with Katki chasing Parsi textile traditions to their origins in Iran, Gujarat and West Azerbaijan. In Mumbai he attends a Parsi gara workshop with master embroiderer Zenobia Davar, learning new stitches like some of those used in traditional jhabla.[1] He Skypes his grandmother back in Auckland and holds up a checked rag (Still Life, Spin & Thrust, 2018) to the camera, ascertaining its provenance and from exactly which market he can purchase more. He delights in purchasing deadstock Czech glass beads from the same vendor that supplied his great grandmother, and is willing to wait months for more to be ordered from Europe in the specific shades that match his Art Deco family home. Dedicated to a complete understanding of his practice, he is frustrated when he can’t tell me whether the warp threads on a particular bolt of silk – one woven on an almost-500-year-old loom in a subterranean kashan workshop – are coloured using natural or synthetic dyes. Underlying his practice is an absolute respect for his materials, no matter how humble. For the works in Agiary Series (2018), Katki starts with squares of handwoven cloth, made by apprentice weavers practising on discarded cotton thread and sold for use as rags in Maharashtra and Gujarat. It is a difficult medium to stitch on, with the slubbed open weave gently distorted in places by the pull of dense embroidery. Instead of emulating the 22ct gold and silk zardozi tableaus he encountered in museums, Katki chooses to honour these quiet, functional emblems of the domestic sphere.

I had found my people – they were women. Up on that desk, garishly festooned with trimmings, the notion of my sexuality was suspended for a moment in the presence of those darling creatures – never to be questioned, or so I thought.

– Journal Extract ii, Monday 2nd July 2018

Katki has inverted the patriarchal institution of contemporary Zoroastrianism by seeking out his own personal female deities, including, not least of all, his own grandmother, who taught him many of the skills he now employs in his work. As the son of a priestly family, Katki was initiated into the Zoroastrian faith, but at a very early age realised he objected to their traditional values. Instead, Katki tells me, he “retreated under [his] mother’s skirts,” finding a more comfortable place in the domestic realm. It is therefore not surprising that many works in Bildungsroman worship female power. Historical Parsi figures like Madame Bhikaiji Cama, revolutionary designer of the precursor to India’s tricolour flag, are captured in beaded vignettes alongside an ancient pre-Zoroastrian clay fertility goddess, excavated in Tappeh Sarab, in Iran. Another of these, Pink Breakfast Table (2018), features a scene as humble as its title suggests. Katki is creating a history in which sacred spaces and childhood memories are treated with equal reverence. He often references Anāhitā, the deity of fertility and water whose origins go deeper than Zoroastrianism (and he is thrilled by the thought that a renegade ‘Cult of Anāhitā’ might still exist today). Panel three of his Agiary Series, Temple of Anāhitā (2018) assembles elements which tap in to his own matrilineal history. Stitched above the pediment, if you know how to read it, is ‘The Temple of Women’ in shorthand – the written language which allowed his mother and aunt to enter the workforce in the 1970s.

Zoroastrianism can only be passed down through the male line, and global numbers are dwindling. Katki views the Parsi attitude to homosexuality as less one of straightforward bigotry than a discomfort with disrupting their conventional gender roles – not to mention a potential threat to the production of future little Parsis. As he recounts in his journals, it was therefore an unexpected source of pride for Katki to find so many echoes of himself in his trip to ancestral areas like Tehran, where a museum teashop worker giggled at Katki having the same nose as her brother. Despite his uncertain relationship with the faith he was born into, Katki makes a place for himself alongside other queer Parsis such as Farrokh Bulsara (Freddy Mercury) and poet Hoshang Merchant. Sometimes this is unambiguous – the beaded toran emblazoned with “GOD BLESS OUR HOMO” – and sometimes it only reveals itself to the viewer upon closer inspection: an embroidered roof tiled with the tips of teeny tiny phalluses (Hoshang Merchant Takes his Vitamin D, 2018). In essence, Katki has written his autobiography, saying, “This is a show I’d use if I hadn’t told my parents I was gay. This is what I would say to them about my identity.”

Every major act of kindness performed by our people deserves documentation and fond remembrance, even if it is just me who understands & remembers.

– Journal Extract vii, Sunday 16th September 2018

Bildungsroman is a push and pull between celebrating the elements of Parsi culture that Katki feels need immortalising, and critiquing those that have led to its decline. Katki incorporates moments of minor rebellion into his work, such as when he sketches into Temples & Shrines, Panel I (2018) the outlines of all nine sacred Atarsh Behram fires, usually only viewable to members of the faith. He despaired of finding someone willing to teach him the Parsi art of making torans (beaded valances) until he convinced his sight-impaired family friend, Aunty Dolly, to revisit this lifelong skill – one she would never teach a non-Parsi, but one that Katki doesn’t want to keep to himself. Mindful of the importance of documentation, Katki has created three primary sources through which his history can be read: the photographic record of his journey, shared in part in the gallery and extensively on Instagram; the journal entries he wrote, a selection of which are reproduced as gallery text; and finally, the work itself. By including a few select artefacts like the woven hat he wore as a child, his mother’s stenographic study book, and an embroidered book of prayers, Katki gives context to his work without overly historicising the show. The two screens at the sides of the gallery, on which works are stretched or draped, were created in collaboration with fellow Parsi-born New Zealander Farzin Adenwalla of Bombay Atelier. They emulate those found in fire temples and historic houses – a hint of the Parsi environment for an uninitiated Aotearoa audience.

There are two pieces in particular that Katki tells me he views as “the closest I get to having created a historic document.” Each work in the diptych of Diaspora Series (2018) features an ornate border, that visual cue a viewer familiar with traditional Parsi gara might expect. In Udwada (2018) (named for the town which contains one of the nine Atarsh Behram), Katki incorporates delicate fragments of his great-grandfather’s 200-year-old cotton sudreh, which are appliqued onto the woven canvas with sampler-esque lines of embroidery, neat rows of conventional stiches occasionally breaking into gestural shorthand squiggles. Underneath the shirt fragments is a densely embroidered micro-patchwork of colour blocks which gestalt-shifts into lines of washing hung out to dry. All of this applied to a repurposed striped handwoven 1940s tea towel, as Katki leverages off the ingrained history of his material to enrich the narrative.

Right now I am lying on a divan in absolute bliss, recounting the experiences and interactions I’ve had with textiles in Kashan.

– Journal Extract xvii, 1st October 2018

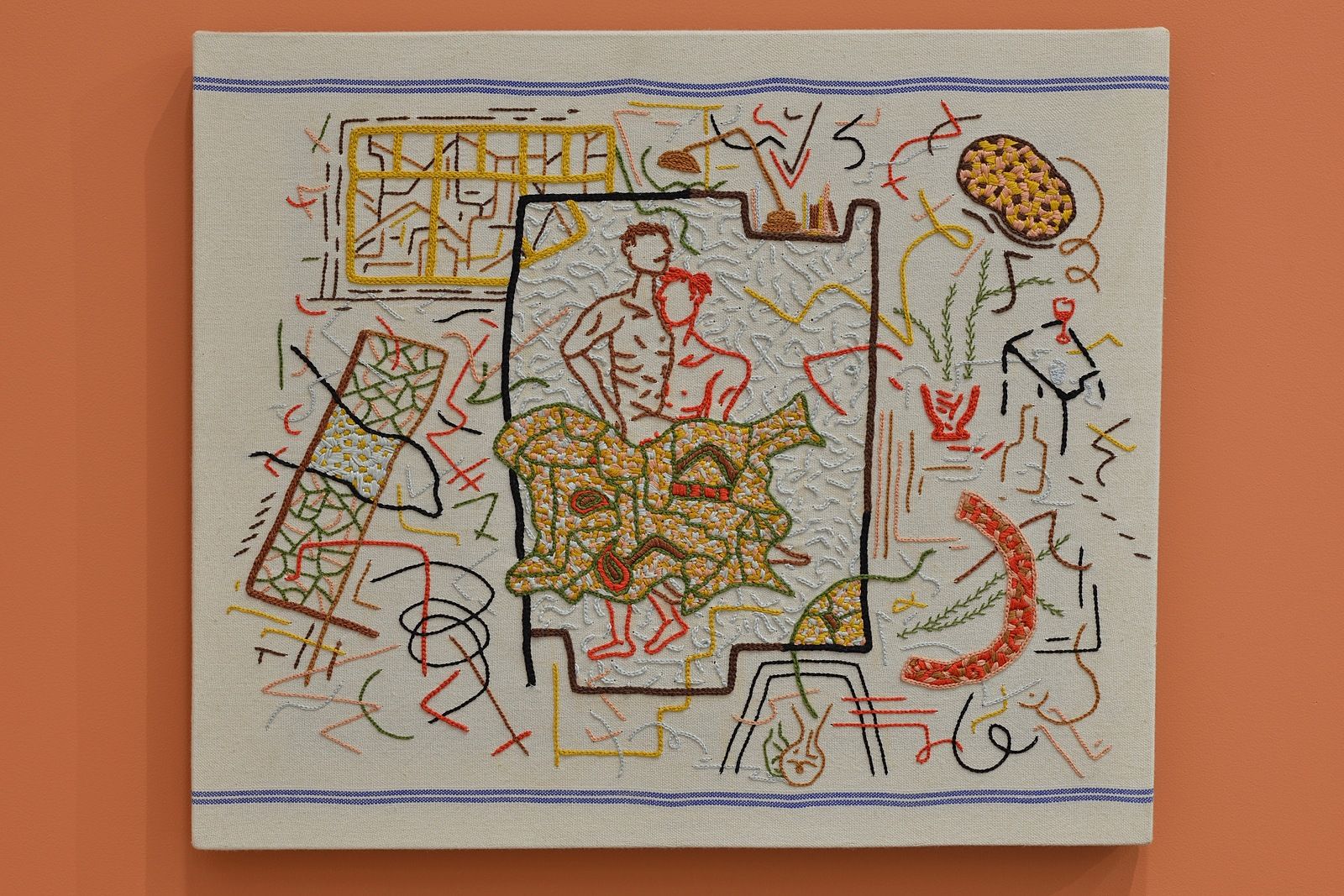

Those familiar with Katki’s previous work might expect a room full of chain-stitch curlicues, recording a synaethesiac response to his journey. These hallmarks still abound but are scattered amidst uncharacteristically literal depictions of elements such as the Faravahar, a winged form which is the most well-known icon of Zoroastrianism, again providing a way into the narrative for viewers who may only be superficially aware of symbols from the Parsi religion. His nine-month trip provided time for focused work and an expansion of his skillset, evident in the stained-glass blocks of colour done in time-consuming satin stich.Often these are achieved through a tambour needle technique he learned in Mumbai, commonly used in commercial Parsigara embroidery. He also celebrates the tactility of his material in different ways. Stretched over board, the qualities of the weave are brought to eye level. Or they are draped in a parabola over suspended bars, encouraging the viewer to engage with the work as a piece of sculpture. Handwoven handkerchiefs that belonged to his grandfather are displayed lightly crumpled, an echo of their former purpose.

There has been much written about the ‘subversive stitch’ – of women using needle and thread to connect the medium’s status as ‘women’s work’ with the relative denigration of textile art. This connection is blurred in a Parsi context. Indian commercial textile production is male-dominated but among the middle-to-upper classes, where Katki’s family is situated, embroidery as a pastime has female connotations which amplify his queerness. This aspect makes his work potentially unsettling for a Parsi audience; he would love to show Bildungsroman in India, where same-sex relationships were decriminalised just seven months ago. Closer to home, although Katki is by no means the first male New Zealand artist to use textiles as his medium,[2] he still believes there is a stigma about men who stitch – he was disappointed that none attended the embroidery workshop he led alongside the exhibition.

Katki’s choice of material isn’t a defiant refutation of the art-craft divide. Rather, it is a tribute to those elements of his culture and upbringing that he cherishes. Unable to find his place in the patriarchal conventions of traditional Zoroastrianism, the textile techniques taught to him by his mother and his grandmother have become the tools with which he illustrates his heritage; the quiet, intimate moments of equal scale to a grander narrative of Parsi history. There is a fundamental spirit of generosity in his willingness to share this story. Katki’s exquisite work creates a space that is private, personal and a privilege for the viewer to be let in to.

Bildungsroman will tour to Otago Museum, opening in late October 2019 in their People of the World gallery.

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with Blumhardt Foundation. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.

[1] As defined by Katki in his exhibition text, a gara is “a typically Parsi silk textile, hand embroidered with a very fine silk floss, using the zardozi style of embroidery among other fine needlework techniques. As a garment it is draped and worn similarly to the Indian sari. However, in style, the gara combines early 19thcentury neoclassical motifs, Chinoiserie narratives and Mughal-Persian iconography – creating a dense and unique mélange.”

[2] Significant New Zealand practitioners include weavers Ian Spalding and John Hadwen, tapestry designer Gordon Crook and quilter Malcolm Harrison.