Please take the rope from my throat so that I may sing

Talia Marshall explores how James Baldwin's novel, Another Country, touched her, and how his themes of acceptance and racial equality are still crucial today.

In this powerful and moving essay Talia Marshall explores how James Baldwin's novel Another Country touched her, and how his themes of acceptance and racial equality are still crucial today.

This essay contains offensive language and descriptions of racial, verbal and physical abuse.

I dreamed at sixteen of making James Baldwin’s novel Another Country into a movie. It was a silly idea because it would make a terrible film – too much talking, no guns and no plot. Just women ruefully picking tobacco from their lip in a taxi cab. And Don Cheadle is too old to play Rufus now, and Billy Crudup can’t be Vivaldo because he was cruel to the pregnant actress with three names, running off with Claire Danes like that.

I read Baldwin’s gay novel Giovanni’s Room at the same time, but Another Country is my favourite because it had these women in it: white, privileged Cass with her WASP, horse-riding New England girlhood, and Black, imperious and beautiful Ida who was aloof and suspicious of her dead brother’s white friends. Cass and Ida were proof Baldwin paid some attention to the inner world of women even if he imprisoned them in their sex as equally as men.

All his writing toils with the fact and cage of the body. The black body and the white fear of its darkness, and the cultural incomprehension at the heart of American life. His paradoxical and gospel-fed vision was that the only way to solve the ‘negro problem’ was to set white people free from their prejudice, given the subjugating nature of power even for the powerful.

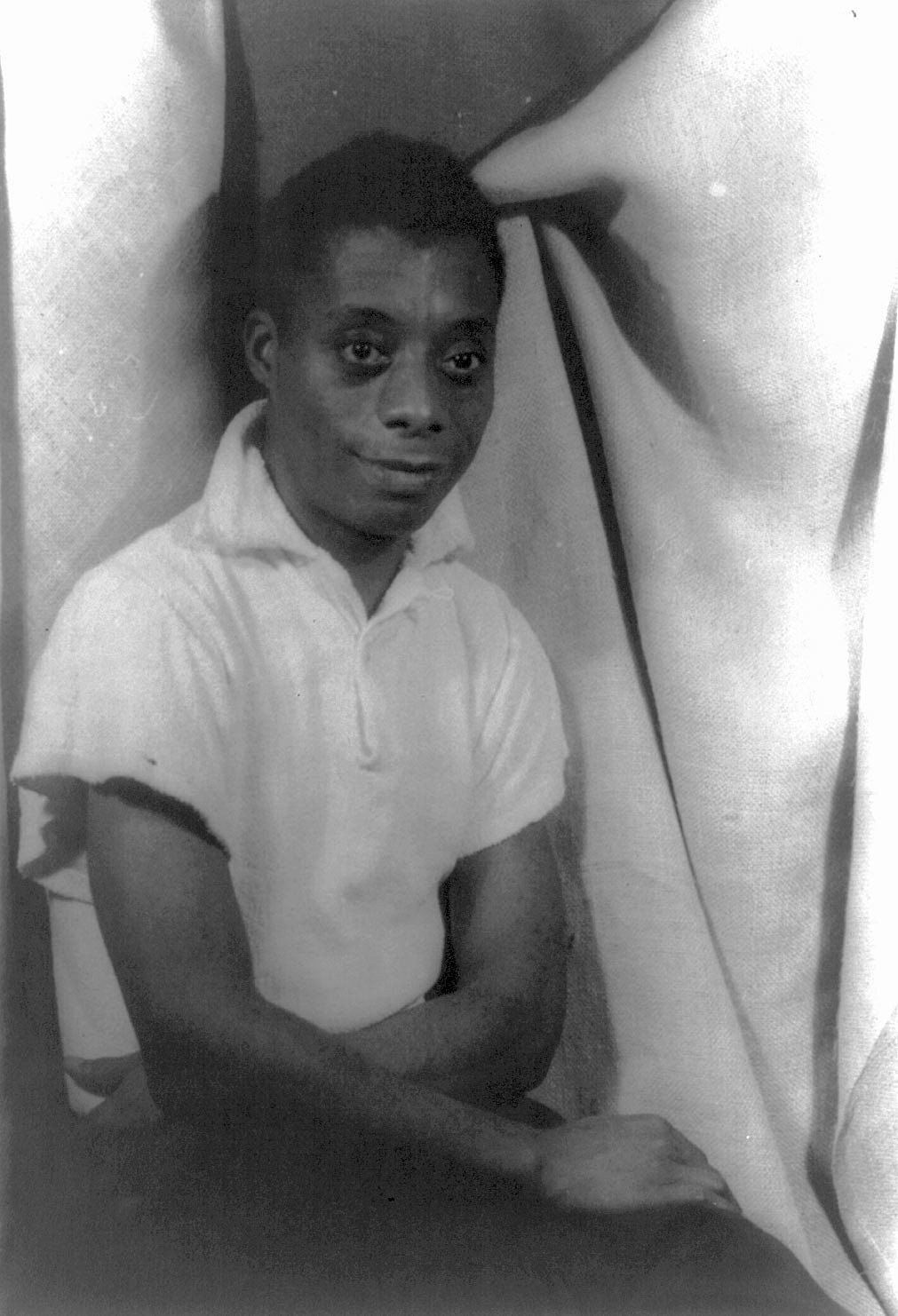

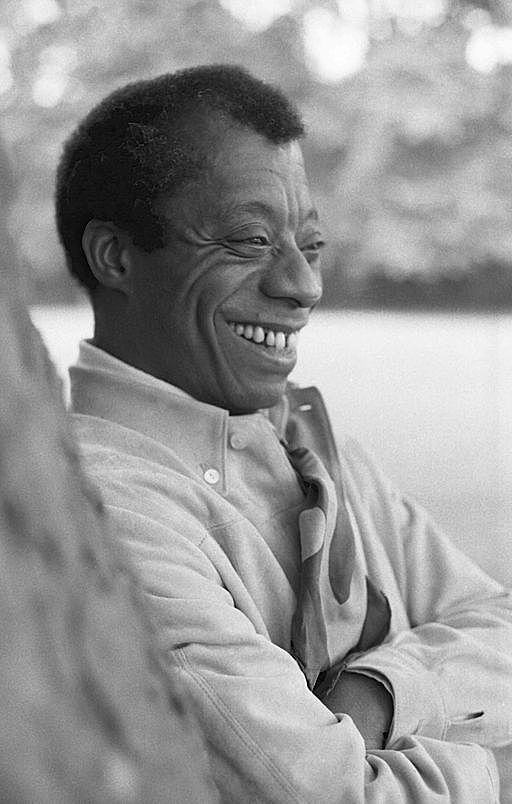

James Baldwin was the double negative: Black and gay, and blessed with a frog-like lovely/unlovely face and boy-preacher airs; the greedy reader who devoured every single book in the Harlem library as a child; the ear for mixing the street talk of Harlem and Brooklyn, and the Beat chatter of the Village with the heady modernism of James and Joyce. Baldwin is often accused by critics of having superfluous amounts of empathy, and at times this compassion for the human condition slips into purple, gushing sentimentality. Like Disney for the bohemian set, Baldwin’s writing can be the literary equivalent of a relentless zoom lens shot of people’s faces and all their wretched, spilling emotions.

He was dead and intellectually out of favour when I was studying books at university as the ivory towers that first embraced him resented his chipping away at their conceits. Then, the academy bore a thinly veiled distaste for the themes and excesses of his fiction and essays; here was someone prepared to talk about being Black and gay as a way of talking about what it meant to be human. We studied Ralph Ellison instead, and I hated every single miserable page of Invisible Man.

Strange then, that in these times of intense, shimmering calamity, Baldwin’s voice is once again at the eye of the American hurricane; that so little has changed as to make him re-appear as both prophet and preacher. The contemporary revival is spearheaded by the post-festival circuit release of I Am Not Your Negro, a documentary film by Raoul Peck that features Samuel L. Jackson voicing Baldwin’s last unpublished writings about the lives and deaths of Malcolm X, Medgar Evers and Martin Luther King.

If Baldwin was still alive I imagine he would have fought to have the documentary called I Am Not Your Nigger (although the working title of the unpublished manuscript was Remember This House). The opening shots show him using the word with real relish beside the smacked-looking face of Dick Cavett. But America still isn’t ready for ‘nigger’ to be in a title. Baldwin insists in another interview from the documentary that White America no longer needed “their nigger” so were intent on “killing them all dead.” He tells the interviewer he is not ‘their nigger,’ he is a man.

All his writing toils with the fact and cage of the body. The black body and the white fear of its darkness, and the cultural incomprehension at the heart of American life.

James Baldwin never got on with the Pantherite radical Eldridge Cleaver; Cleaver found him too forgiving and too gay. Which is funny, I guess, because some of Baldwin’s more radical ideas about race come from a deeply Christian way of thinking, a world-view he shared with King.

Baldwin’s personal radicalism shifted when the native New Yorker (who’d been let away with so much at the fringes of the elite, lurking in their libraries) finally witnessed the state of racial murder and hatred of his own people in the South. He was full of rage then and holy thunder; his non-fiction becomes livid and transformative but his fiction, aside from the lovely and subtle first-person female study of If Beale St Could Talk, starts dripping with too much pain.

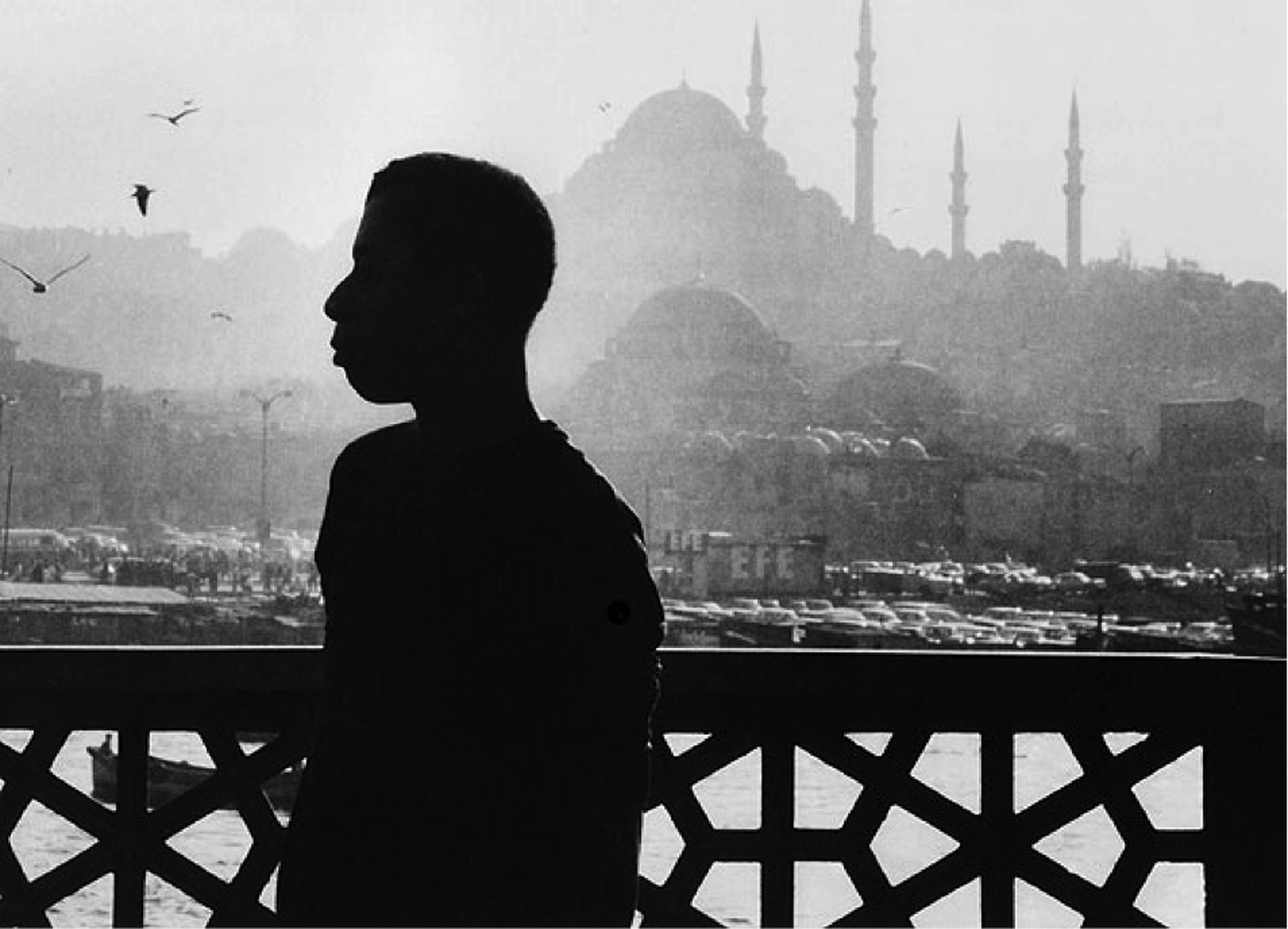

Another Country, his third novel, straddles the stylistic strait between his early fiction and the later, more overblown works. He conquered the beast of it away from America, staying at an actor friend’s in Istanbul. He said if he’d stayed in New York he would have ended up dead. He was an exile from America through Paris and, like his friend Nina Simone, he only felt like he belonged once he left.

Writing Another Country in America had made Baldwin despair and contemplate suicide, the mirror of his character Rufus whose plummet from the George Washington Bridge triggers the events of the book. Not that the novel has anything resembling a conventional plot; it’s just Rufus’ friends and his sister Ida, sliding around the Kinsey scale together in an attempt to deal with their grief and uselessness in the aftermath of his death.

Rufus is an abusive, playful and tortured jazz drummer whose descent is caused by the destructive relationship he forms with Leona, a broken, poor white woman from the South. When he meets Leona he charms her with her own Southern hamminess, telling her she is ‘no bigger than a minute.’ Leona replies that ‘a minute can be a powerful thing,’ but Rufus comes to see the hate for their relationship everywhere. They fight and he beats her.

I wasn’t sure about Rufus, but at sixteen I inhaled the way these people spoke to each other. There is something spare and lyrical about the way Baldwin animates a room amongst the dialogue, and how deftly characters are revealed by the grace of their gestures and manners – Cass, who always lights the cigarettes of the people she’s being sage to, the ice melting in their copious drinks, the terrible beatnik way they call each other ‘baby.’

Of all the novel’s characters, Cass sees the most. Despite her privilege or maybe even because of it, she’s the one who Baldwin’s inner voice seeks to inhabit. She’s the only one in the cast of characters not trying to make it as an artist, but she always looks like she’s in a painting: Cass the empath smoking at her window with the view of the Hudson River, wearing a ‘dusty orange dress,’ completely unaware of how compelling she is; Cass wandering around MOMA with her too large handbag and umbrella for the rain.

She goes to Rufus’ funeral with Vivaldo, an aspiring Italian American writer from Brooklyn and Rufus’ closest friend. In the taxi, on the way there, she realises that she can’t be bareheaded because no woman in the late fifties steps inside a church without a hat. Vivaldo unhelpfully tells her to tie the belt from her dress around her head, but she stops in Harlem to buy a black scarf to cover the blondness. When she gets to the funeral she discovers, with little surprise, that she and Vivaldo are the only white people there.

But we so want others to witness our real self, maybe... it’s the most slippery thing of all.

In another taxi cab, riding again from the Village to Harlem along Seventh Avenue, Ida mocks Cass, saying that she probably thinks of Central Park as just a park. Ida says to her it’s ‘a jungle,’ as if Cass is only a white married mother who risks nothing by being alive. Because she can’t believe Cass endangered her complacency by sleeping with Eric, her brother Rufus’ former lover; because despite her own adultery, she can’t, as a Black woman, believe a white woman would be so feckless as to throw her security with a white man into the air like it was confetti.

But we so want others to witness our real self, maybe because it’s the most slippery thing of all. Cass asks for this from the gay and sexually ambivalent Eric when she cheats on her husband with him. And this complexity of desire and weakness is what Baldwin covers best in his fiction, and what he encouraged people to do when reading his essays: to bear witness to and imagine the testimony of others; to bear a big heart for their trouble, for their suffering and the cruelty we are able to inflict upon others, often without knowing.

This reminds me of the most heart-breaking scene in the genius T.V. series Transparent. At Sarah and Tammy’s wedding, Jeffrey Tambor’s transgender character Maura has gone to so much effort to appear as the mother of the bride, and looks delicate and transcendent in white, but is still called ‘he’ by the photographer when asked to adjust her spot in the family photo. The photographer inflicts cruelty without knowing, and shatters Maura's artful construction as easily as a finger through a web.

We all say terrible, stupid, hurtful shit. Such statements are not necessarily emblematic of our being unless they form a pattern of attack; but, in our fallibility, the hardest thing to translate into politics, that grinding machinery of the collective, is the mysterious movements of love. Decades ago, Baldwin suggested that being Black was really white people’s problem, he saw them lost in the abject of their own projection. Today that seems to apply to everything, not just racial hatred. In this age of intensive moral hygiene we are stuck at the intersection with multiple, competing, blinking agendas and, underneath all the politeness and the identity pile-ups, rage keeps cooking like lava under the road.

[T]he hardest thing to translate into politics, that grinding machinery of the collective, is the mysterious movements of love.

Recently, and closer to home, amidst the bulging cacophony of the language wars which pass for leisure on social media, I found myself, as just an observer, battling rage and confusion amongst the immense smack people were shouting at each other in a 140 character format on Twitter. In between the Emily Writes/Idris Elba thirst/apology fever, the Mad Butcher saying mad racist shit on Waiheke and the Jimi Jackson blackface pus, I started to feel a bit triggered, a word I’ve never used with much gravity.

I started muttering ‘intersectionality’ interspersed with ‘big black cock’ to myself accompanied by a freakish, maniacal giggle. I was suffering a clear case of language derangement, but I kept my mouth shut on social media as I’m just a coward who will only fully unleash the breadth of my personal injustice on a call-centre worker or via an email. But I also had to stop and ask then: Why was I so bothered? Why did I think it had anything to do with me, and also, why did I feel so silenced?

*

It was because I used to love someone who called my son a ‘nigger.’ ‘Dirty Nigger,’ in fact. A tautology when an angry white man says it. A handgun of hate.

It is my whakamā that I permitted this to be said about my son as casually as rotten milk is poured down the sink. That I stayed. And by osmosis, he absorbed all that venom into his chocolate brown skin, his whakapapa bending back through toto to Māui and Kupe. I’m pretty fond of polishing my genealogy like my long dead whānau are jewellery, but I struggled to stick up for us when it happened because it beggared belief. Months later, I started to shout ‘dirty nigger’ in public, but it was too much, too late.

My son comes from rangatira lines on mine and his father’s taha, yet this is also a grandiose and evasive way of describing our former status as slave owners. During the musket wars, our ancestor Tutepourangi gave away 1,000,000 acres to avoid becoming a slave or pet for Te Rauparaha. This act was to avoid torture, and to avoid his daughter carrying pumpkins of clean water for the elite and vicious to drink from, her body a commodity of no real value to itself.

And still, that intolerable word ‘nigger’ has its own seething history, and even though this history doesn’t belong to me I think there is no more offensive word in English than ‘cunt.’ But I will tolerate both if said with affection, as in, ‘Wot’s up nigga?’ said from one bro to another. Also, ‘he’s a good cunt’ is a term of endearment, and there’s something sweet and devoid of the penis in that. ‘Cunt’ and ‘fuck’ are exceptionally good if one has hurt oneself, or alternately if someone’s being a complete wanker. ‘Jesus’ goes well with ‘cunt’ and ‘fuck,’ as do ‘face,’ ‘bitch,’ and ‘asshole.’ That said, ‘nigger’ will never be ok for certain people to use, and the cues Black people have given about its usage needing to come from only their ‘I’ and their quarter continue to be loud and clear.

I’m thinking of Michelle Blanchard’s stony dignity after the Real Housewives of Auckland ‘boat nigger’ fiasco. When someone uses the word – as Julia Sloane did in this case – to extinguish equality, or jokingly remind Blanchard of her own comparative privilege, there is nothing jolly hockey sticks about it.

But. I suspect the reason the white Māori Jimi Jackson donned shit-face for a Kapa Haka sketch was to co-opt and express vicarious solidarity with the history of black oppression. Our colonial history is so vastly different from the gospels of American slavery that he was quickly labelled a racist.

My son likes Jimi Jackson and used to make his own terrible jokes about the K.K.K. Initially I lectured him about the history of lynching and burning crosses, but then I asked him why he thought it was funny to wear a white sheet at Halloween with his brown legs poking out; why he thought it was funny to say, ‘Kill all the blacks’? He replied that he made those jokes so someone couldn’t say it to him, or about him, first. Our history is only unique until someone erases it by tarring us with the same brush. My son’s appalling humour and Jimi’s joke channel an internalised resistance that is attendant to the story of power.

Māori have been taking the piss out of the visitors since they arrived. That’s the bass note to the Billy T. chuckle, and our subtle, self-mocking comedy has seeped into the national psyche parallel to settlers’ laconic deprecation. ‘Too much, bro’ with a raised eyebrow usually means not enough, not even. Of course Māori can be racist, some of the most racist shit I’ve ever heard has flopped out the mouth of a Māori, but our racism has another timbre and flavour to it based on alternate hierarchies and modes of exclusion.

Jimi Jackson’s shit face, however offensive, taps into our own history of loss. When I hear some Māori use the word ‘nigga’, I don’t flinch, as I suspect it’s a way of loosening the noose at our throats in the secret fraternity of the broken nigga.

We were a status-loving, tribal and mercurial people who suffered multiple trespasses on our mana. As a result, there is something mournful and self-shaming to our humour. Jimi Jackson’s shit face, however offensive, taps into our own history of loss. When I hear some Māori use the word ‘nigga’, I don’t flinch, as I suspect it’s a way of loosening the noose at our throats in the secret fraternity of the broken nigga.

My son though, at sixteen, is an insanely healthy, happy, life-loving person; so beautiful, from my maternal bias, I can’t bear to look at him. And isn’t this mauri, the Māori life-force he conducts more of than me? Isn’t this what we also despise about brown people in this country – his delightful, easy naturalness, that choppy strum with the guitar, the supernatural grace for games and the whatumanawa of our hupe at a tangi? The stereotypes about our cultural character as Māori that Pakeha have co-created and seem to both shun and covet (perhaps most tellingly in the spectacle of the flash mob haka) speak to the fear that, even post-colonisation, parts of our magic, mana and whakakatakata as tāngata whenua persist past the ridicule.

My boy looks darker than me and his father; his double dose of whakapapa means he is more subject to the envy and loathing of others. But as Baldwin pointed out, darkness, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder.

My experience of racism as a café au lait Māori has been minimal, and all the times I have been told ignorant hatey stuff by Pākehā I’ve been secretly thrilled like I’m part of the gang at last. As a caregiver in a dementia unit, I once walked into a room where an old man almost spat and said, ‘Not another fucken islander,’ because he was a bit blind and a bit deaf. I sat beside him and yelled in his ear that I was Māori because if I’d said ‘tāngata whenua’ he wouldn’t have known what I meant. ‘That’s even worse,’ he said and I laughed with anger because I knew exactly what he meant. Apart from his contempt, he was just a powerless old man. I made a facecloth warm and was gentle enough trying to remove the crust from around his eyes.

*

About the time my son was being called a ‘nigger’ to me I started to fret for him more than usual. I would check that he was breathing when he was asleep, like a new mother checking her infant. I read every fantail in the Rata for signs of disaster. If he was half an hour late I would start to drive or walk the neighbourhood, imagining the worst. Fearful, I suppose, that he would be taken from me because I didn’t deserve him. Eventually my son was called things that hit home worse than nigger, and I left. I wasn’t being brave. There was no choice. Loving my son has never been a choice.

Then my son left to go Space Camp in the not-so-sweet home of Alabama, the same part of America that Eric and Leona are from in Another Country. I was so frightened about him going away that I refused to believe it was happening. I made no cheese rolls in a zero fundraising effort, and I was rude to the nice people who sent emails. He didn’t have a pounamu to wear like St. Christopher, and I thought this meant he would be incinerated in the plane on the way; and it would be my fault for not being ‘Māori enough’ and failing to get him one despite the cousin’s gallery.

I tried to make jokes with him before he left about becoming the first Māori in space... I reminded him of the Peter Gossage book about Hine-nui-te-pō in which Māui enters the cosmos through the legs of a woman; I said that technically this made Maui the first man in space.

I tried to make jokes with him before he left about becoming the first Māori in space, but also that he shouldn’t take his rainbow poncho in case he was kidnapped by some crackers in a pick-up looking to lynch someone Mexican rather than Black. I reminded him of the Peter Gossage book about Hine-nui-te-pō in which Māui enters the cosmos through the legs of a woman; I said that technically this made Maui the first man in space, that he’d got there through a goddess.

My son always shuts down at such talk from his mother, and I kept my school, mall and church massacre visions to myself. Lies! I begged him not to share his own black humour in America, but it turns out the Yanks are more safety conscious than me. He got told by a large man in chinos that there would be no running at all, of any kind, even on the spot of the space camp grounds. Brilliant.

But it’s also a country where if you’re running and you’re black there is a high chance you’ll be shot in the back. Then there will be a brief and cinematic fuss but no justice. Baldwin’s beautiful and screaming incomprehension sixty years ago at such atrocities still makes too much sense.

*

Re-reading Another Country I had to blank certain passages (the abysmal sex scenes) to retain my respect and love for the text, and for the characters who, at sixteen, I felt were the most true and glamourous people in the world. I remember I was happy to know such people could exist because fiction has always seemed more real to me than the mirage of life. I still feel around for them in the nonsense of my head. I still wish that I was Cass and the boy preacher had conjured me up with his airs.

In Another Country, James Baldwin writes that this is ‘all the dreamer wants and wishes for, for reality not to molest’ and peel back the dream. Now I have these blanks where my love used to be. These points in the road where the oil no longer sings into the air and my incomprehension at my old life scratches off the Twink. Words are tasteless and odourless, but like the most discreet poisons they still have the power to kill depending on who uses them as a weapon.

During one of their many fights, Ida screams “white motherfucker” at Vivaldo because he calls her a “house nigger” and they end up rolling on the floor, laughing at themselves and still in love. By the end of the book she has told him of her affair with the conniving T.V. producer Ellis. A betrayal driven by her fundamental distrust of Vivaldo, her cultural suspicion at his unfamiliar goodness, and her disbelief that, despite being white, he intends her no harm.

Ida holds all white people responsible for what happened to Rufus, but at the same time bears no compassion for what he did to Leona. Leona ends up walking the streets of New York, barefoot in the snow, looking for the son taken from her in the South. She doesn’t find him and is put in the bin of Bellevue instead.

Ida is determined not to go under like her brother, and in doing so she pushes her own head beneath the water in the risky baptism of her confession. We are only made privy to her motivations on the last pages, and we only know her by what she chooses to tell us. Really, I wanted to be Cass but to look like Ida, shoving her secret garlic into the pork chops and humming a tune.

On his last night on earth, Cass tells Rufus that no one can begin to forgive other people unless they can first forgive themselves. It’s true and trite, and not enough to save Rufus from his shame at what he did to Leona. He leaps off the famous bridge to escape his own stink. Even though Cass seems to look into him and intuit his regret, he hides from her and the scale of their diffference. He says he’s been ‘uptown,’ a euphemism in this instance for being broken.

I am not living in Baldwin’s America. This is another country and we do things differently here, and even with my own raging at the lights, I have some faith that my capacity for forgiveness will turn green over red at his jaundice. It’s certainly been long enough since I was at the mercy of such futile levels of anxiety about the children.

Just last week I went out in the car searching for my son. It was well after dark and he was running the inlet where we live. I permitted myself to feel – without any whakamā – the full-feathered indulgence of my love, hope and dwelling place existing in him. I permitted myself to feel the shift from wolf mother back to hen.

And here now, coming around the bend like a train from a tunnel into te ao mārama, oh my light in the darkness here he is.

The title of the essay, chosen by the author, references 'Tangohia mai te taura i taku kaki kia waiata au i taku waiata' (Take the rope from my throat that I may sing my song.) These words were spoken by Mokomoko, a chief of Te Whakatohea of the eastern Bay of Plenty, as he was about to be hanged at Mount Eden gaol on 17 May 1866. More information can be found on Te Ara.

For another take on Baldwin's contemporary relevance, see Orlando Edmonds' "Integration and Denial: Reading James Baldwin after Don Dale"