Feminine Painting/Painting Feminine: An Exchange Between Painters Claudia Jowitt and Amber Wilson

Claudia Jowitt and Amber Wilson discuss femininity as aesthetic and being a ‘serious’ painter

Claudia Jowitt and Amber Wilson discuss femininity as aesthetic and being a ‘serious’ painter.

This exchange appears in the catalogue for Claudia Jowitt’s exhibition Liberal Application at Bath Street Gallery, Auckland. The text has been slightly edited for publication here.

*

Claudia Jowitt: I’ve been thinking quite a bit, since the end of my Masters last year, about ideas of ‘decoration’ or ‘excess’ in relation to the paintings I’ve been making. Earlier on, when I was producing more pared back, muted geometric abstractions, I was hugely resistant to the idea of my works being perceived as ‘feminine’ or ‘decorative’, as I felt like these terms were often used as negative assertions in the academic art field – used in a way that deemed the work passive or non-serious.

Here, it’s worth referring to the opinions of Adolf Loos. In his 1908 essay, ‘Ornament and Crime’, he lays out the acts of decorating and ornamenting as superfluous and excessive. While the text depends on Eurocentric assumptions about class and race, Loos makes some points that are still pervasive today – particularly his suggestion that the overly decorative is a “waste of human labour, money, and material.” He also states that the “urge to ornament one’s face and everything within reach is the start of plastic art. It is the baby talk of painting.”

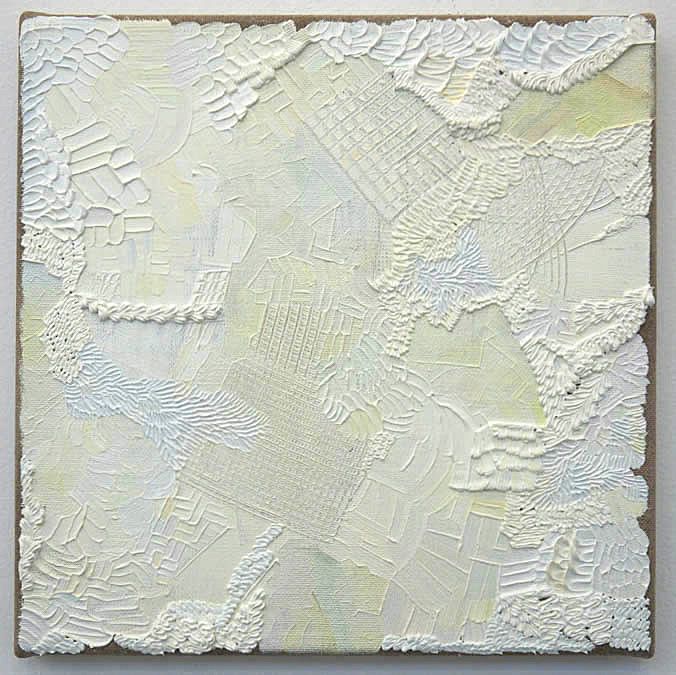

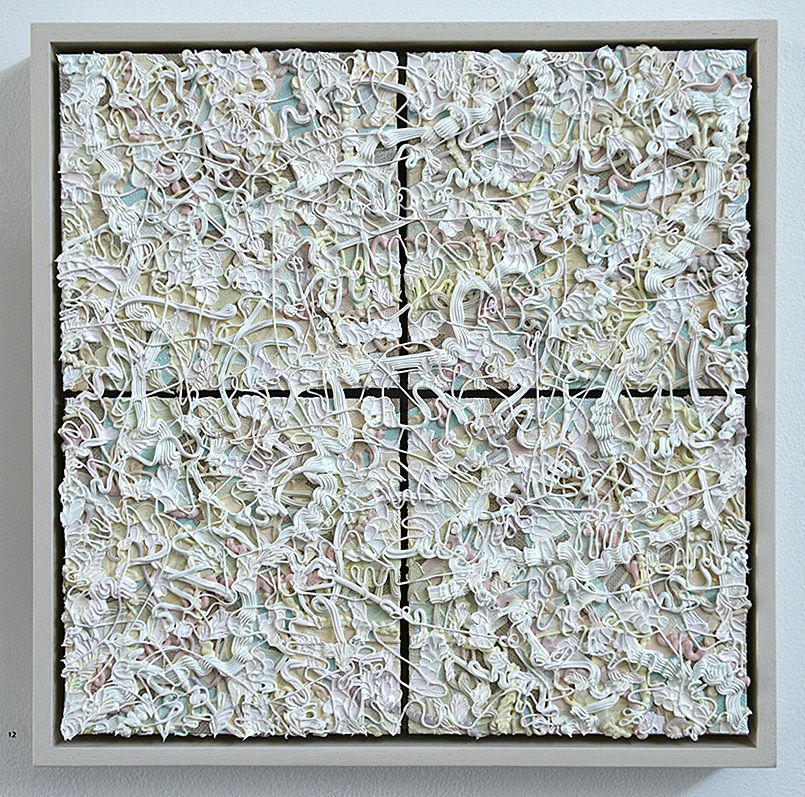

Last year I started to turn against some of the methods and practices that I had learnt to make ‘serious’ paintings, amping up the femininity, and using almost pastiche, slapstick methods of application. I’ve been squeezing a hell of a lot of paint through cake icing sets, and using lots of kitchen implements. Why not be all the things I was trying not to be, rather than being restrained, because I thought I was being a more serious painter?

Funnily enough, I’ve been told my more recent work suits my personality more! I’ve also been introduced as the “campy cake painter”, which may have been someone throwing some serious shade at me, but I actually didn’t mind the title. Haha!

I’ve been looking towards the work of Laura Owens and Charline von Heyl, and the fabric patterns of Memphis of Milan. I want to articulate a use of cliché or pastiche of style, motif and technique as a conscious stratagem, rather than a fall-back option or Get Out of Jail Free card. I think of it more as a hierarchy leveller, not some sort highbrow irony. As Thomas Lawson states in his 2003 essay, ‘The Unbearable Lightness of Painting’, Owens achieves in her paintings “acknowledgement of an almost guilty pleasure, the recognition of the power of cliché to please us in an uncanny way, to bring us outside ourselves.” Just a few things I have been thinking about recently.

Maybe I’m late to the party on the whole owning the feminine possibilities of painting. But for some reason, I found it quite a hard thing to figure out. I’m still figuring it out really. Of course, the majority of my teachers have been male, so maybe it just hasn’t been something I’ve really felt comfortable discussing in an academic setting until recently. Or maybe it’s just an age thing.

Maybe I’m late to the party on the whole owning the feminine possibilities of painting. But for some reason, I found it quite a hard thing to figure out.

Amber Wilson: I’m interested to hear you speak about how you have reclaimed for yourself the idea of the decorative. Surely, in 2016, we can use this term without shame, and begin to loosen it from an ossifying historical context? A lot has happened since Loos, who was deep in the social and artistic climate of an emerging modernist aesthetic. Clement Greenberg certainly furthered the marginalisation of the decorative, positioning abstraction and decoration in opposition, in search of a pure painting.

However, maybe for this conversation, it is more pertinent to put this sort of thinking aside and focus more on the personal … It is imperative to allow your own inclinations and interests to exist, and to have the courage to let them steer your practice, free from concern or anxiety around your perceived degree of seriousness as a painter.

I find it disappointing that it might seem like certain interests or approaches to making art are considered less serious in and of themselves. We are all responsible for constructing the permissive and inclusive community we want to be part of, and that involves making space for and supporting a multiplicity of approaches to practice. We cannot sanction certain areas of inquiry as more serious/worthy than others.

We are all responsible for constructing the permissive and inclusive community we want to be part of, and that involves making space for and supporting a multiplicity of approaches to practice.

It must be a great relief to you to no longer feel concerned about whether you are taken seriously or not. But why do those feeling emerge in the first place? Why the necessity for seriousness? What a waste of energy to be concerned about it, energy much better directed towards making work! Swirling around this are notions of freedom and equality, and it puts me in mind of a phrase Chris Krauss repeats in I Love Dick, “who gets to speak and why”.

The feminine as gendered aesthetic … It seems that in order to be considered critically engaging, paintings characterised by delicacy or softness also have to contain some qualities of subversion – an element of some kind to challenge or work against. This is an aesthetic situation I personally respond to, but I have also, at times, felt uncomfortable with it, as if it reflects an expectation that as practitioners we must be at all times ironically self-aware, lest we be caught in the act of earnestness. I’m very much in support of earnestness, as long as the ability to be critical is not lost.

Over the past two years, your work seems to have become less about image-making and more about the physical process, your direct engagement with the paint. Your work has increased in scale, and you now appear to be almost sculpting your paintings. Though there is a consistency in your practice, in attention to surface, pattern and colour.

You are using tools designed to decorate confections right? Is this what you are referring to when you say you want to use cliché, as a way to speak into the work, or as a direct affirmative action, rather than ironic staging? I wonder if when you or your work are described as ‘camp’, what is really being spoken about is the mannered quality of the paintings.

There is an overly elaborate quality to your application, which has a lyricism and musicality to it, in turn connecting with theatricality – qualities associated with the notion of camp. Do we have to talk about Sontag here? Sometimes her ‘Notes on “Camp”’ aren’t all that useful in discussions of painting. Perhaps you have been working on your own definition of camp …

Claudia Jowitt: You’re right. It’s a big relief in regards to relinquishing concerns about being taken seriously when engaging with an aesthetic that can be read as more ‘decorative’. As stupid as it seems, I was buying into and perpetuating this idea myself by even giving credence to opinions of what is and isn’t serious. In mentioning Loos, I referred to an out-dated throwback that still colours some schools of thought about painting today.

Part of the pressure to be making something that appears outwardly ‘serious’ is definitely propped up by the historical canons of painting that we all learn, which are undoubtedly biased towards a masculine lineage of expression and the validity of that. It does become a question of navigating your way through a long, loaded history of painting and value judgments.

I don’t ever want my work to be read as ironic; it’s not a way of thinking I buy into.

The point about earnestness is a good one. All the work I make is incredibly earnest. I don’t ever want my work to be read as ironic; it’s not a way of thinking I buy into. I want my work to be more democratic. The whole ‘wink-wink nudge-nudge’ approach to painting or art in general just breeds an elitism that excludes viewers from an experience unless they are in on the joke. I don’t want to make work that is exclusionary. This is not to say that I don’t want to make work that’s thought provoking. But I’m not out to induce jeers.

When I speak of pastiche and cliché, I’m thinking of my use of exaggerated pastel tones, a variety of different tools (i.e. icing bags, decorating tips, spatulas, tile grouting combs, etc.), and painterly gestures that at certain moments refer to various past styles or motifs.

I like your articulation on the idea of camp as an affirmative action. A definition of camp that is pertinent to my work is: a) something so outrageously artificial, affected, inappropriate, or out-of-date as to be considered amusing; b) a style or mode of personal or creative expression that is absurdly exaggerated and often fuses elements of high and popular culture. Camp can be employed in a staging of subversive action against its assumed lowbrow status. Camp-ness critiques that which it is mimicking in blowing out the proportions of things and disrupting normative ideals. An excessiveness or heightened decorative quality goes hand in hand with this.

Also this idea you raise of a move towards the sculpting of paintings is particularly relevant to my most recent work. I’ve definitely been enjoying testing the limits of the physicality of paint. Last year, I was introduced to the work of Bram Bogart, which takes the sculptural element of painting to the extreme. I am combining oil and acrylic now. Acrylic and its possibilities are new to me, but it allows for varied qualities of layering and adhesion. I was having difficulty with the limitations of oil – more specifically, with its drying time in large quantities – after a few issues with chunks falling off canvases. Necessity forced a change.

The assertiveness of that volume of paint pushing out into the physical viewing space between substrate and viewer is appealing. I want to make use of the focal points of peaks and pits in paint, in a way that oscillates rhythmically and does not provide one clear route into breaking down or deciphering a given work.

Nor do I want to give the viewer one clear definition of what femininity is through the medium of paint. It is a multiplicity of things expressed all at once, simultaneously quiet and loud, hackneyed and serious, passive and assertive, slow and fast, reserved and excessive. These inherent contradictions/resistances can give the painterly form both momentum and relevance. I am only starting to unpack the possibilities, but I’m excited about the paths this provides for future work.

*

Claudia Jowitt holds a Master of Fine Arts degree from the University of Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Arts. She was recently named the inaugural Pacific Artist in Residence at the Dunedin School of Art at Otago Polytechnic. Amber Wilson holds a Master of Design degree from Unitec Institute of Technology, Auckland. Both Jowitt and Wilson were included in the 2013 painting show Porous Moonlight, curated by Imogen Taylor for Papakura Art Gallery.

Liberal Application

3 March to 2 April 2016

Bath Street Gallery