Paper Shrine: A Review of Amadeus

Sam Brooks reviews Auckland Theatre Company's production of Amadeus

Sam Brooks reviews Auckland Theatre Company's production of Amadeus.

Amadeus is a beast of a play. For many people it's most famous for the 1984 Academy Award-winning film, focussing on the the largely one-sided and largely fictional feud between prodigal genius Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and embittered court composer Antonio Salieri. When I saw that Auckland Theatre Company had programmed the play, I blanched a little. The last thing the world needs is a traditional period rendering of Amadeus. But considering director Oliver Driver and musician Leon Radojkovic were collaborating on it, having torn Jesus Christ Superstar to shreds a few years ago and built it from the ground up as a rock concert, my fears were quelled. This wasn’t going to be Amadeus as it was when it premiered at the National Theatre nearly forty years ago.

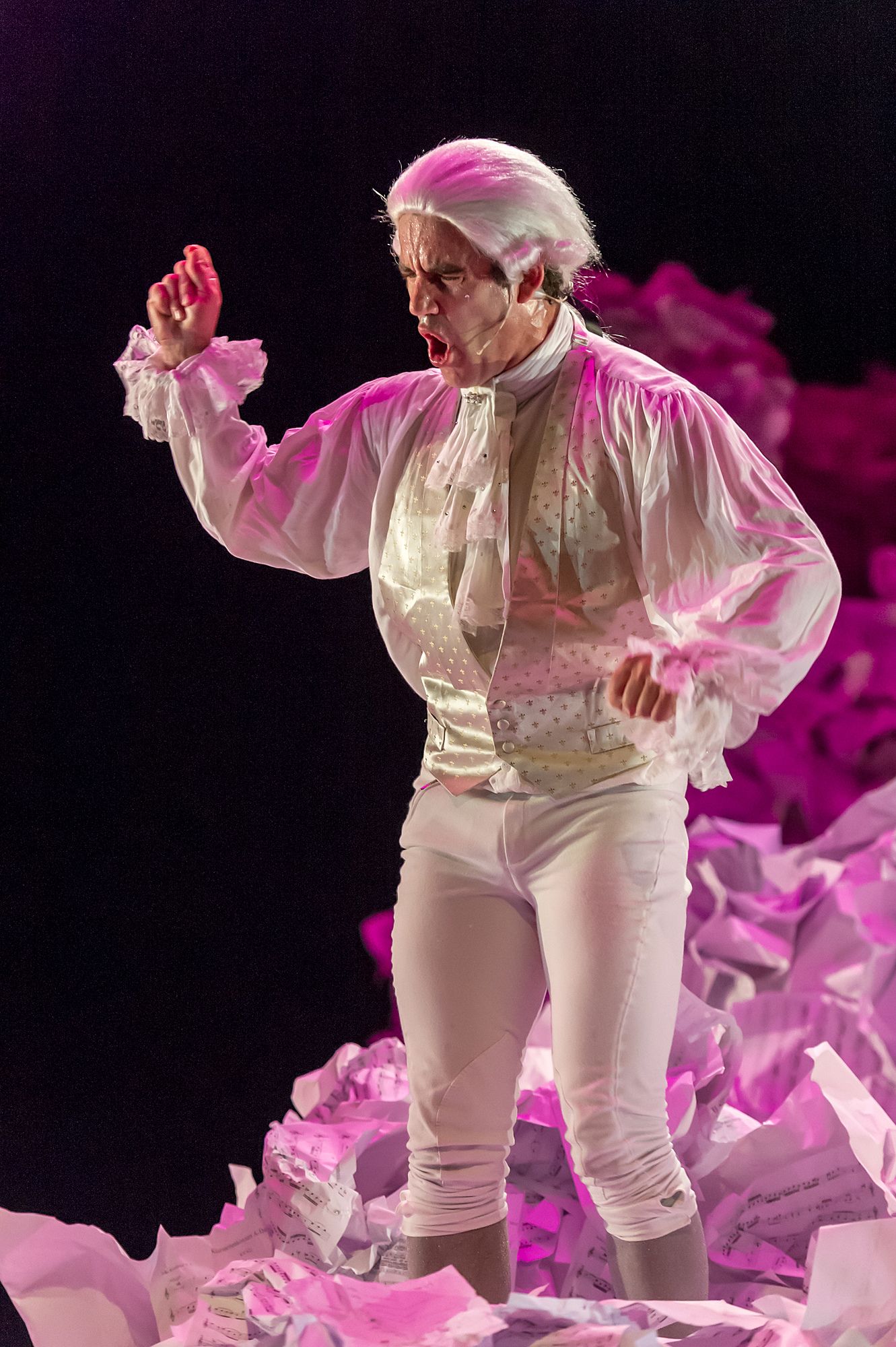

The curtain comes up and we’re greeted with thousands of crumpled up pieces of paper – a shrine to the tortured artist.

Auckland Theatre Company’s production of Amadeus is a defibrillation that this play desperately needs. This is clear from the moment the curtain comes up and we’re greeted with thousands of crumpled up pieces of paper – a shrine to the tortured artist. Set designer Ella Mizrahi did beautiful work with her own company Celery Productions, including transporting us into a real life forest in Blackbird Ensemble’s Into The Wilderness and transforming the Basement Theatre space into a dive bar with Silo Theatre's Blind Date Project and this is her most stunning work yet. It takes us into the mind of Salieri who’s driven almost mad with his jealousy of Mozart and his rage at an absent God, and this tumult literally takes up the entire stage. The paper stage is a hell of an image, and it’s one the production plumbs throughout, with bits of paper flying about the stage through actor movement, an air-drop from above, and even, at one point, via a large fan.

Equally as striking, and key to the play’s success, are Leon Radojkovic’s arrangements of Mozart’s music. Each of the major plot points in the play revolves around the premiere of one of Mozart’s operas and Radojkovic does an excellent job of rearranging what we usually hear played by a much larger orchestra to be played by a smaller band, adding modern elements of guitars and drums while still retaining the violins and clarinets. In this way he adds an edge to Mozart’s music. Nowhere is this more crucial than a moment in which we hear one of Salieri’s compositions – a trinket that he’s composed to welcome Mozart into the court. It’s a nothing of a piece, but when we hear Mozart rearrange and ‘fix’ the piece, it’s edgy and radical. Mozart’s music doesn’t necessarily sound that way to us in a world of tropical house and EDM, but Radojkovic’s rearrangements show us how revolutionary Mozart was in 18th century Vienna. His music sounds bigger, it sounds braver, it sounds better.

These two elements of music and set design are the most striking right from the start, and definitely linger the most after the curtain falls, but the rest of the design also pushes the boundaries of the play. Jo Kilgour’s lighting design gives the already textured set even more texture – the paper seems literally glow shades of red and pink at some points – while fashion designer Adrian Hailwood’s costumes, especially for the women, are stunning and memorable, with opera singer Catarina’s red gown being a particular highlight.

Director Oliver Driver doesn’t exactly deconstruct the play, but what he does is cleverly give us a lot to look at and a lot to listen to in order to engage us. It’s a bold directorial choice, and crucially, it doesn’t actually distract from the content of the play, but instead allows the best moments of the play to hit the audience even harder, namely the final fifteen minutes where Mozart is frantically composing Dies Irae, a cacophony of performance, movement and sound.

Which brings us to the play itself. Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus is forty years old. Both theatre trends and audience expectations have shifted in that time. There’s a stateliness and a remoteness to Amadeus that not even Driver’s direction can break. This is a play that begins with a ten minute monologue that very cleanly sets up the play’s conflicts and themes. This is the kind of play where men speak about ‘having’ a woman, with complete seriousness. It’s the kind of play that ends up being less about human beings, and more about ideas.

He starts out at the end of his rope and there’s nowhere for the performance to go from there.

This is not in itself a bad thing, we could use more plays that aim this high, but where Amadeus falters as a piece of writing is that our way into this story is through a character who is hard to empathise with. Salieri’s main conflicts are with Mozart and with God; there are long monologues in which he rages against God for not rewarding his piety with genius, instead giving him only the ability to recognise genius. Shaffer spends a ponderous amount of time making sure that we understand this, and whatever momentum and life Driver has injected into the production falls dead when we have another monologue from Salieri in which he details his every grievance, his every scheme and his continued anger.

Hurst’s performance doesn’t help this. From the first word, this is Michael Hurst’s Salieri – every trace of F. Murray Abraham’s underplayed Salieri that you might remember from the film is nowhere to be seen. This is a Salieri whose every emotion is externalised for the back row to see. It’s a capital B Big Performance and it’s a bigness that matches the boldness of the design, but he plays Salieri as more twisted demon than tortured human. He starts out at the end of his rope and there’s nowhere for the performance or the play to go from there. His Salieri is so far gone that it’s impossible to hear the character, his plight or even the text under the noise of the performance. It’s difficult to watch this Salieri, and even harder to engage with him a relatable human being.

The rest of the performances inject a necessary life into dialogue and into situations that desperately need it. Ross McCormack’s Mozart is a constant breath of fresh air. McCormack is an accomplished dancer and choreographer, and he brings those talents to his Mozart. He captures the electricity flowing through the character and is so wildly present and energetic whenever he’s onstage that he’s a joy to watch. The play presents Mozart as some kind of conduit for God, and McCormack plays that to the hilt. It feels like he’s channeling something otherworldly through his body – like he’s been hit by lightning.

As Mozart’s wife Constanza, Morgana O’Reilly doesn’t have a lot to work with; Constanza is a narrative convenience, with a naivety that completely contradicts the character’s world-weariness, but O’Reilly finds what comedy she can in the character and mines it well. A scene in which Constanza makes what she feels to be a necessary bargain with Salieri and then immediately regrets it is genuinely haunting. It’s the first time there’s someone who feels like a real person onstage, with relatable emotional stakes, and O’Reilly makes this as raw as it needs to be.

Laughton Kora, Byron Coll and Kura Forrester round out the rest of the ensemble, with Byron Coll’s Emperor being a comic highlight of the show. The Emperor’s insistence that Mozart writes “too many notes!” is maybe the most famous phrase from the screenplay. That line seems to be the source and soul of Coll’s Emperor; a fake French wannabe who wants to be seen as intelligent and benevolent without actually doing any of the work. Opera singer Madison Nonoa also does beautiful work as young soprano Catarina. Her soprano is powerful and clear, and from her perch on the top of the paper set she strikes a compelling image.

At its best moments, the production makes us feel the talents of all those involved. It’s quite a feat to make a play that is as stately and remote as this into something resembling immediacy, and whether it’s Ross McCormack’s stunning debut performance or a group of designers allowed to run free and wild, Oliver Driver’s direction brings the entire thing together. And while the production can’t shake free from the ponderous shackles of the text, it’s still an absolute blast to watch it try to do so.

Amadeus runs from Tuesday 9th – Saturday 20th May at ASB Waterfront Theatre. Tickets available here.