All Who Live on Islands

Rose Lu reflects on growing up as a Chinese New Zealander in Aotearoa and what it means to be visible or invisible in the stories we read.

Rose Lu reflects on growing up as a Chinese New Zealander in Aotearoa and what it means to be visible or invisible in the stories we read.

Do you remember the food at school camps? The frosted plastic dispensers spitting out cornflakes, Ricies and the Sultana Bran that only teachers ate. Fruit salad from a kilogram can, pieces of apple and pear steeped in syrup for so long that they all taste the same. And for dinner lasagne, in industrial-sized baking trays.

Lasagne was a dish I’d only heard about, and I couldn’t wait to try it. I knew it had mince, tomatoes and cheese, and that the construction involved layering. I learnt the word ‘lasagne’ long before I tasted my first bite. My eyes had seen the word written down, my ears had heard it spoken aloud, and my brain had put two and two together. Who would have guessed that the ‘g’ and the ‘n’ next to each other would have produced that sound?

A red slab was slopped on my plate. I fumbled with the knife and fork. The lasagne tasted unlike any food I ate at home. Further down the table I could see Winnie pushing her food around her plate. My cheeks reddened. I looked back down at my plate. I hoped I didn’t look as unpractised with the knife and fork as she did.

Winnie was my buddy at school camp and I wasn’t happy about it. Winnie didn’t get jokes. Winnie wore tracksuits with embroidered teddy bears and didn’t know that she was supposed to be embarrassed. When Winnie started at school teachers made sure to introduce us, even though we weren’t in the same class.

This was Palmerston North in 1999. Aside from Winnie and I, there was just one other Chinese kid in my entire primary school. At times the outside world didn’t seem like a place that I fit into, so I turned to books to understand. I read in the car. I read on the toilet. I read in the shower. I read when I should have been sleeping. I read so much that my mum imposed a five-book limit on my weekly library trips, worried about my constant yawning at the breakfast table, face tipping downward into my bowl of 稀饭 / porridge.

Reading is how I learned about British and American children my age, their lives filled with sleepless sleepovers, bright piñatas at birthday parties, the punishment of ‘grounding’. There were stories about New Zealand children too: I read about Alex Archer, reaching arm over arm to defeat her rival and earn a place at the Commonwealth Games. I read so I could bridge the discomfort of curious strangers, encountering for the first time someone who wasn’t white or brown and not quite knowing what to do. I absorbed culture and language so I could behave enough like them, to downplay the parts of my life that needed to be explained.

At times the outside world didn’t seem like a place that I fit into, so I turned to books to understand ... I read so I could bridge the discomfort of curious strangers.

My family moved from Palmerston North to Auckland, and I graduated to young adult fiction. I read stories about dead best friends that hung around as inspirational ghosts, and identical twins that drifted apart so they could find their own identities. My intermediate in Mt Roskill had a high Asian population. I was introduced to manga and spent my pocket money on stationery.

In my first year of high school, we moved again, to Whanganui. I sobbed for the entire car ride. I didn’t want to leave Auckland. Whanganui had no malls. It had just one inadequate library – no manga, and an additional charge for borrowing anything that wasn’t in the children’s or young adults’ section.

Whanganui was a hard place to adjust to. I was noticeably different once again. Most of my year group had never lived outside of Whanganui. It was hard to find common ground. Someone started a joke that my family ate cats. It was like the joke had nine lives; when I thought it was dead and gone it always seemed to come back. School was a place where boys were boys, and compared to some of the stories told about other kids, I counted myself lucky.

As a teenager in Whanganui, I read books about being in love and having sex for the first time, and learned that the world didn’t end when a relationship was over. I read about overcoming eating disorders and how you should accept yourself the way you are. I read books that depicted subjects like grief, mental illnesses and parental separation with compassion and delicacy – but I never had the chance to read on themes specific to the migratory experience.

From all the books of my childhood, I can recall just two characters of East Asian ethnicity: ditzy artist Claudia Kishi from The Baby-Sitter’s Club, whose room in her Japanese-American household was chosen as the club’s meeting place because she had the best snacks and a private phone line; and weepy Cho Chang from Harry Potter, with her ethnically ambiguous names, mixing ‘Cho’, a common Korean surname, with ‘Chang’, a common Chinese surname.

It provokes strange reactions in us, to be almost invisible in the stories we read. Graci Kim, an Auckland-raised writer, talks about her experience completing a writing assignment on her family at primary school. Her teacher pulled her aside because she described herself and her parents as being “blonde, with blue eyes”, despite their black hair and brown eyes. As a child, she’d thought that type of physical description was a grammatical rule or convention, like capitalising proper nouns. She had thought, in books, it was incorrect to write characters that looked like us.

It provokes strange reactions in us, to be almost invisible in the stories we read.

*

I grew up being told that I was Chinese. The word was constantly forced upon me. People would talk about ‘The Chinese’ in the abstract and I would feel my stomach turn, and watch for signs that their definition included me. Even if their intentions were pure, the way that the general public talked about race made me feel uneasy.

Bereft of any better views about China, I slowly started believing the same stereotypes as the people around me. I read Chinese Cinderella by Adeline Yen Mah, a memoir about an unlucky and unloved Chinese daughter – the only English-language novel of its kind I had access to. Never mind that it was set in postwar Hong Kong, I took it to confirm the brutality of growing up in China. I thought of China as an impoverished, totalitarian and lacklustre country, and books and media never showed me anything to the contrary. Besides, why else would we have left? Why else would my parents have renounced the place so resolutely?

At school I manufactured a clear divide between me and Chinese students in the International Students Block. It was in my best interests. They were teased for their self-given names – ‘Stone’, ‘Ice’ and ‘Neo’. One friend had a Chinese homestay student at their house, and confided to me that the student lacked basic personal hygiene. I took this as a sign of my successful integration. I was Chinese, but I wasn’t Chinese Chinese.

When I moved to Christchurch for university, at first I noticed how white it was compared to Whanganui. But again, it didn’t take long for my sense of normal to adjust. My life became crowded with new experiences like flatting and going to gigs, and I stopped reading.

By then I had become expert at presenting myself as a certain type of Chinese. There was no denying how I looked, but I also made sure that my New Zealand accent would not be denied. I was quick to understand racism when it manifested as disbelief that I was ‘from’ Whanganui, or amazement that my English was so good, but I never saw a problem with being labelled as a ‘banana’, or when my friends commented that they ‘forgot’ that I had a race.

It wasn’t until I moved to Wellington after university that I wondered if something about how I saw race was off. I volunteered as a phone counsellor at Youthline, and in one training session I blithely commented to another trainee, Sophie, “Oh, but your English is so good!” upon hearing that she had been educated in Hong Kong. Our supervisor, also of Chinese heritage, overheard and cracked up at my faux pas. Sophie had received her schooling entirely in English, from an international school. But because she presented as partly Chinese, I unconsciously made a few assumptions about her. I had acquired a passive form of racism that is pervasive in well-intentioned New Zealanders, one composed of ignorance and neglect.

In Wellington I also reconnected with an old friend from my intermediate school in Auckland. Lucy invited me to a hot pot gathering at her house. I turned up with a packet of fish tofu and was surprised that everyone looked and talked like me; I hadn’t been in an environment like that since leaving Auckland ten years ago.

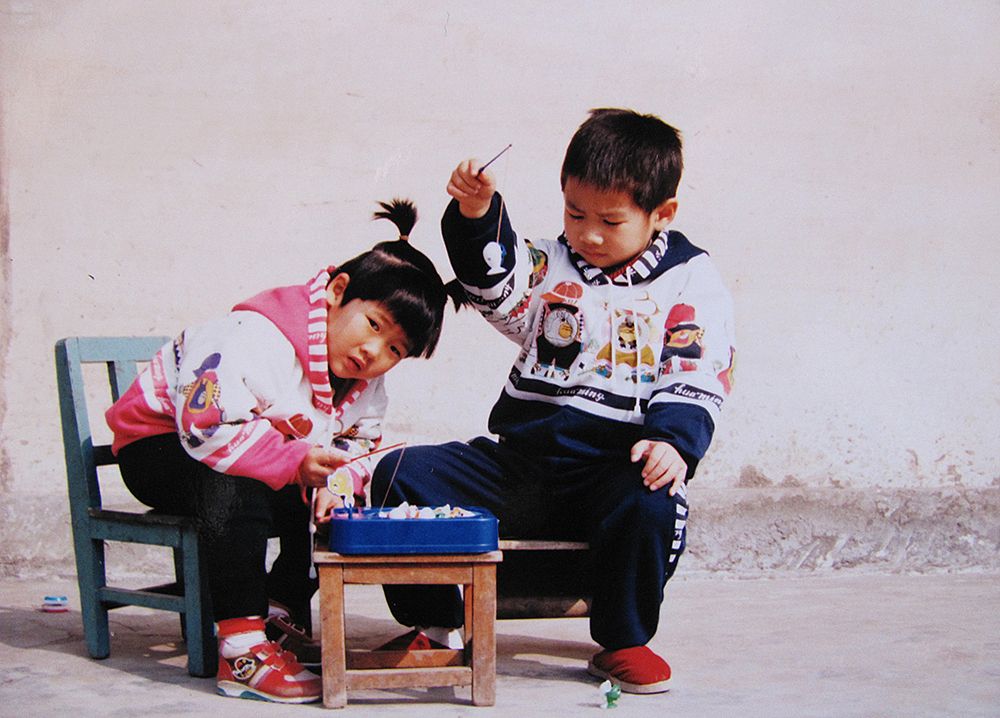

Lucy and her friends reminisced about spending semesters abroad in China and regular visits with family. For me, China had frozen when we left. December 1995 had become a still frame, the snapshot pinning my family’s image of China. We left while China was taking a preparatory breath, on the cusp of an exponential boom. I had no memory of what the Pudong skyline looked like. I was five years old and everything about that time was tawny and subdued.

Since leaving at age five, I’d only been back to China twice: a barely remembered trip at eight years old, and another, begrudgingly, at 21. As there weren’t many other points of reference, I had assumed that lack of contact with family back in China was normal. But now, hearing my new friends discuss their experiences with modern China, understanding all the different paths their families took to emigrate, it framed my life in a different light. It piqued my curiosity about this place that I was always told I was from, but knew next to nothing about.

*

In 2016, I spent four months studying in and travelling through China. My first few weeks in Chengdu were difficult. The cultural difference punched like raw ginger, the incessant honking of vehicles, the sharp shouts. I couldn’t understand the local Sichuan dialect, and residents were loath to switch to Mandarin when they spoke to me. My explorations were punctuated by constant surprise: street corners crowded with 串串 / chuanchuan carts operating well past midnight, the freedom of people’s behaviour in public, how modern and convenient the cities were.

At Sichuan University I enrolled in one-on-one Mandarin classes. I learned that language was less about memorising words and more about using them in different ways. 你吃了吗? / Have you eaten? is a way to say How are you? In shops, staff enquired with 请问你需要些什么?/ What do you need? rather than May I help you? – changing the subject of the sentence to suit a less self-centred culture. I started to realise that all the times my parents and I had talked past each other were likely a result of cultural and generational misunderstanding rather than a lack of a common language.

As my confidence in the language and culture grew, it became a game for me to see how long I could have a conversation in Mandarin before my imperfect pronunciation became apparent. I took every opportunity to talk to people about their lives. The slowness of my Mandarin speech meant I did more listening than talking, that I heard people speak without the misguidance of my assumptions, that I could hear their joy, their pride at being from here. There was so much depth and complexity hidden in the contrasts of the ordinary. I heard stories seldom told in Western media. I was fascinated by the ways that people made sense of their place in the world, and the chorus of their opinions across this big land. Coming from Aotearoa, a country of people humble to a fault, I never expected Chinese people to be so damn proud. People had such deep knowledge about Chinese history, classical literature, the preparation of specialty foods in different regions.

In conversation, the inevitable and important topic of home would come up and I would start to say 上海 / Shanghai in addition to 新西兰 / New Zealand. Neither part of my answer was ever challenged. In one of these first exchanges I was given the word 华裔, a term for overseas Chinese people. In this country I wore a term like ‘expatriate’, unlike the other word, 外国人 / foreigners. Unlike the label I was often given back home.

The stories I heard began to fill the 20-year gap of my family’s absence, and painted a picture of the things that we had left behind. I saw the shape of the life that nearly could have been mine, and saw the differences as texture and colour: neither good, nor bad, they simply were.

Before I spent this time in China, I had never missed it. I hadn’t known what to miss. I focused only on its deficits, the perceived wrongness of something that is different. As I understood what being Chinese meant to me, I cast off a shame that had started so young that I never realised I was carrying it around. I looked back on my childhood, my typically Chinese homelife, and wondered where all this embarrassment had come from.

Before I spent time in China, I had never missed it. I hadn’t known what to miss ... As I understood what being Chinese meant to me, I cast off a shame that had started so young that I never realised I was carrying it around.

*

After my first trip to China as an adult, I started looking for stories about living in the intersection of cultures. A lot had changed since the last time I read prolifically. Social media had become ubiquitous, and on Twitter I found a plethora of literary journals and writers that published the kinds of narratives I was interested in.

The majority of the writing I found was Asian-American or Asian-Australian. I read about the experience of diasporic peoples and came to identify common tropes; the wish for blonde hair and the rejection of language, the coming-of-age nausea of being simultaneously undateable and exotified, the indignation towards white chefs appropriating our food so they can charge double the price for half the flavour. I read about the liberties afforded by being a ‘whiter’ kind of Asian, the experiences of people who are mixed race, of transracial people – people who are born into one culture and adopted by another.

The first weekend I was back in Wellington, I met up with Nina Powles, a Wellington poet I had met in Shanghai. As we lay licking ice creams at Days Bay, both wobbly from being freshly plucked out of a Shanghai winter, I asked Nina for recommendations of authors who bridged Chinese and other cultures. She raved about Jenny Zhang, promising an email with links to some of her essays.

Later I would find out that, like me, Zhang was born in Shanghai and moved overseas at five years old. And, like me, she has a brother nine years younger. When I read her work, there is not only the sense of reading something inherently interesting and exquisite in its execution, but also a sense of being read back by the text itself. Her stories have touched on a part of me that needed to be seen, that had felt absent from the dialogue around me. Her latest book, Sour Heart, is a collection of stories that are messy, strange and full of the sourness of being put in a new place.

This May, I travelled to Auckland to hear Zhang speak at the Auckland Writers Festival. As I looked around at the faces of the attentive audience, I was surprised to see that even in Auckland, the room was filled with mostly older white people. Afterwards, I queued to get my book signed. Zhang was extremely popular, and it took 45 minutes for me to have my turn. Finally reaching the front of the line, I suddenly became flustered. I was standing in front of one of my literary heroes and had not prepared what to say. I gave her a feijoa from my bag. In return, she wrote “Thank you for the sourness” in my copy of her book.

When I thought about it later, I realised what I wanted to say was something like 这个水果是新西兰的特产 / This fruit is a specialty of New Zealand, because in Chinese culture it’s important to know about the specialty foods in the place that you’re from, and high regard is shown in gifts of fruit.

At the Wellington Writers Festival, I met Sharon Lam at the ‘New Asia, New Zealand’ session. Last year she gained her Masters in Creative Writing at the International Institute of Modern Letters, the same course I am taking now. We jokingly established an exclusive ‘Asians at the IIML’ club; in the long and lauded history of the school, there have been only a handful of Asian graduates.

One evening I went to Sharon’s to make bibimbap. While the earthenware bowl was heating on the stove, I browsed her bookshelf and found a copy of Meanjin, Australia’s oldest literary journal. It was an issue on the theme of Asia, dated 1998. I found it hard to reconcile the fact that our neighbours over the ditch had dedicated an entire issue to Asia, only two years on from Winston Peters’ 1996 election campaign to stop the ‘Asian Invasion’.

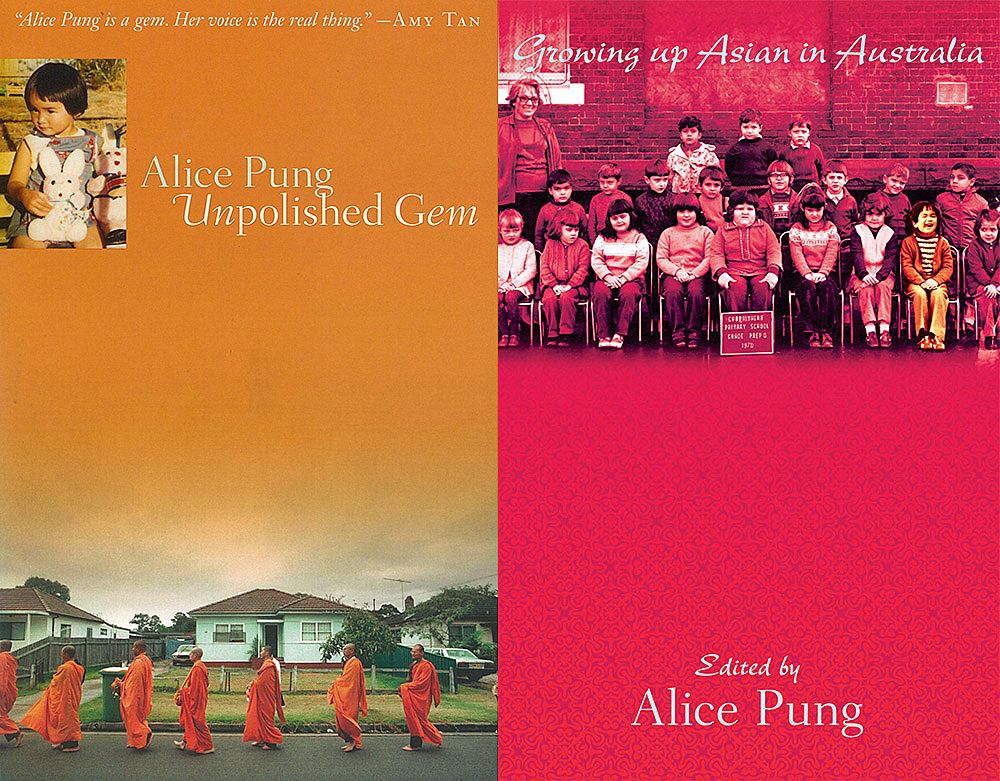

The Asian writing community in Australia has only grown since then. Shu-Ling Chua, a Melbourne-based writer, emailed me a long list of Asian-Australian authors, literary journals and magazines. Her top recommendation was Unpolished Gem by Alice Pung, which she described as “life changing”. After reading it, I could see why. Pung’s memoir of growing up in Footscray is set in the same decade and location as Chua’s own childhood. Pung went on to edit the anthology Growing up Asian in Australia, a cross-genre compilation of musings from Asian-Australians on the topic of identity.

I quickly realised that ‘Asian’ was a useless qualifier for the stories I was reading. This umbrella term has neither enough specificity nor empathy to contain these narratives. If any parallel could be drawn through these ‘Asian’ narratives, then it would be of an experience of marginalisation. But what a shallow lens that definition gives; it belies the ecstasy of eating one’s food, the quiet contentment of hearing a conversation in your mother tongue.

One’s sense of identity and belonging is deeply personal. For the many of us who switch between different modes of engagement at home, at work, on the marae, it’s likely to shift and change. It can’t be measured by looking at the colour of someone’s skin, or the composition of someone’s last name.

People of colour are not born equipped with the vocabulary and knowledge to talk about race. For me it was an active re-education, something I had to seek out as the ideas I needed to hear were never reflected in the books around me. It takes time to understand the complexities that exist within and between different ethnic groups, an understanding that I think it is necessary to keep sharpening. Active work is needed to read these texts and hold the experience of someone of a different culture at their centre. This is possibly an advantage that people of colour have when engaging with texts from cultures outside our own. We are used to being cast as one-dimensional background characters, or being entirely left out; the work of adopting and empathising with other cultures is characteristic of our daily existence.

People of colour are not born equipped with the vocabulary and knowledge to talk about race. For me it was an active re-education, something I had to seek out.

Perhaps the commonality that I found across diasporic Asian literatures is a result of the similar histories of racism toward the Asian people who settled in countries like America, Australia and New Zealand. In Emma Ng’s Old Asian, New Asian, she gives a pithy account of Asian-New Zealand history, starting with Cantonese migrants pursuing the Otago gold rushes of the 19th century, followed by the instatement of the Poll Tax, a policy that restricted the entry of Chinese people to New Zealand. Its later repeal and the removal of a ‘preferred race’ clause in New Zealand’s Immigration Act heralded a new wave of migration from Asia and other non-European countries. Themes in American and Australian history are similar, with their bluntly named “Chinese Exclusion Act” and the “White Australia Policy”.

But there are a few significant gaps in Asian-American and Asian-Australian literature. The particular sense of isolation in Aotearoa that cannot be found anywhere else – an isolation of pointed significance to migrants. The different ethnic makeup of our countries, and our different ways of engaging with our indigenous peoples. Overseas literature falls short of reflecting the particularities of the migrant experience in Aotearoa.

*

The last few decades of publishing in Aotearoa have seen the publication of several books on Asian (in particular, Chinese) New Zealand history. The lives of Chinese gold miners and market gardeners, and the entwined histories of Chinese and Māori communities has finally begun to enter the New Zealand mainstream. The illumination of the lives of these early Chinese deftly tackles one of the most common and infuriating questions asked of Asian people: “Where are you from?” – a question that stems from an assumption that it couldn’t possibly be New Zealand.

When I read the stories of early Chinese migrants to this land, I wonder: where does this place the rest of us – the majority of us – the families that came after the reforms to the Immigration Act in 1987? If we are still striving to have 19th-century stories of gold miners and market gardeners enter the New Zealand mainstream, what will it take for the rest of us to be allowed to tell our own versions of the New Zealand story?

If we are still striving to have 19th-century stories of gold miners and market gardeners enter the New Zealand canon, what will it take for the rest of us to be allowed to tell our own versions of the New Zealand story?

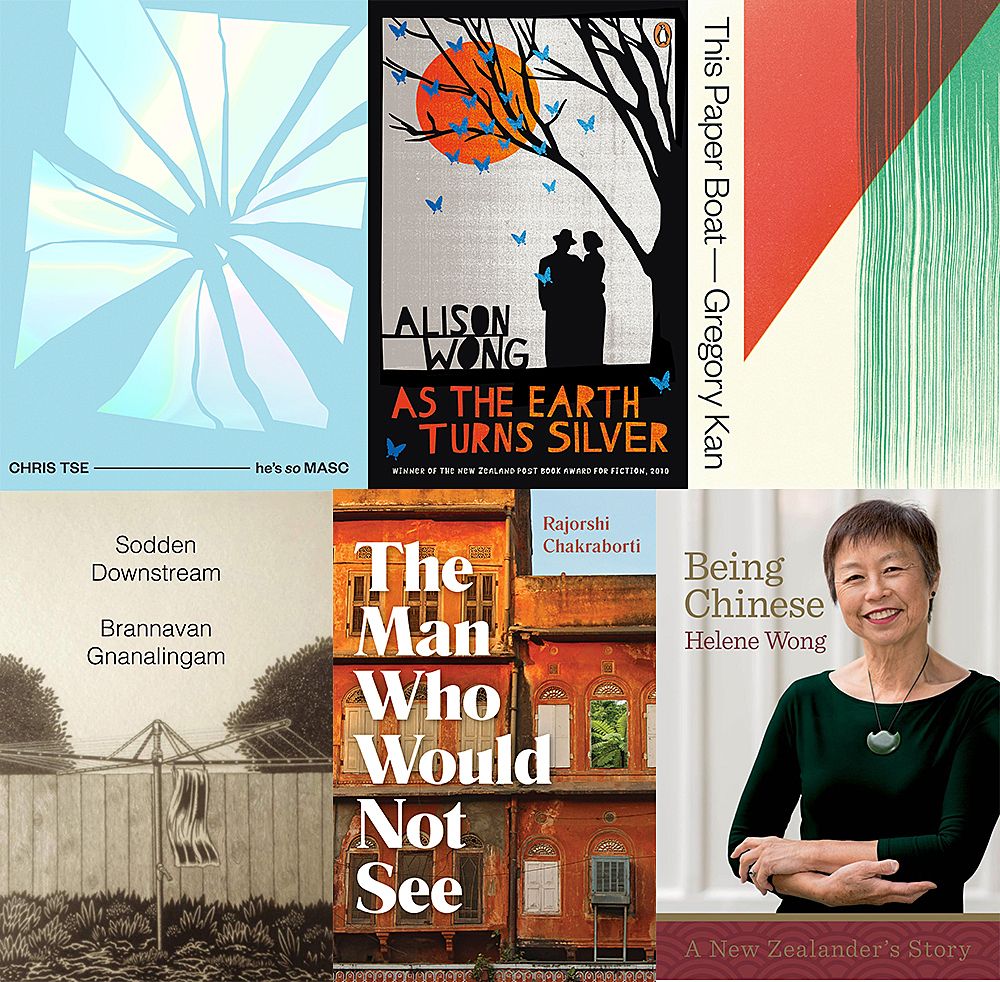

Recent years have also seen the publication of books by a number of notable novelists and poets, such as Chris Tse, who released his glittering second book of poetry He’s So MASC earlier this year, and Alison Wong, with her award-winning novel As the Earth Turns Silver. The works Sodden Downstream by Brannavan Gnanalingam, The Man Who Would Not See by Rajorshi Chakraborti and This Paper Boat by Gregory Kan shed some light into cross-cultural experiences of Sri Lanka, India, Singapore and Aotearoa. Some of these writers choose to write explicitly about race, and some don’t. It’s the visibility of these authors that matters for challenging entrenched beliefs around Asian people.

Where Aotearoa literature still falls short for me is around the experience of the contemporary. For instance, it surprised me how little I related to Being Chinese, a memoir by Helene Wong. Wong writes of growing up as a Chinese-New Zealander in the 1960s and taking a trip to her family’s old village in rural Guangzhou. Her experiences were diametrically opposed to mine: her shock at how underdeveloped it was, the reliance on family members to translate for her. The generational gap between our lives is wider than the cultural gap I find when reading contemporary Asian-American or Asian-Australian literature. For my generation of migrants, it’s still necessary to look overseas when looking for our stories.

It feels like the conversation about the experiences of contemporary migrants is just getting started in Aotearoa. Asian people have started to gain traction in the arts in the last few years, and while there are many talented people leading the charge, it feels like the writing community is still forming, not yet thriving. There is still a long way to go until we reach the same critical mass as writers from overseas communities. We can continue to develop through a culture of support and critique.

*

When I started this essay, I was hoping that I would find a definitive answer to the question, “Why aren’t there more Asian writers in Aotearoa?”, but unsurprisingly it’s a complex issue.

Being emotionally, mentally and financially capable of pursuing a career in writing is difficult in Aotearoa. There are a limited number of places to publish and get your work seen, and not all of them have the means to pay their contributors. I don’t know any writers in Aotearoa who don’t have some other type of work, and they’re lucky if it’s relevant to writing. Migrants often have families with higher needs or expectations, and these factors can compound at the intersections of sexuality, mental health and disability. Often people with the most urgent things to say have the least resources to do so.

A strong thread in New Zealand culture advocates staying quiet and being stoic, and a lot of migrants come from cultures that also believe in the importance of keeping your head down. For us migrant children, it feels like we learn this lesson twice, it is pressed into us with double the weight. It then becomes twice the barrier to overcome before we can believe in the importance of our own stories.

Then there is the disconnect between Wellington, home of the largest literary community, and Auckland, home of the largest migrant community. The most exciting writing on migrant identity that I’ve found has come from Auckland, in the format of self-published zines such as Mellow Yellow and the Migrant Zine Collective. These zines don’t have to water down their content for a predominantly Pākehā writing community, but they are also ephemeral, and lack the distribution and publicity networks of publishing companies.

While writing this essay, I thought it might be more constructive to consider the question, “How can we support more Asian writers in Aotearoa?” or “What would we gain from having more migrant voices?” Aotearoa New Zealand’s nascent identity could do with more diverse viewpoints. Currently it reminds me of my teenage self, stumbling along, listening to the loudest voices rather than the truest voices.

I want to move the conversation forward. Aotearoa has sizeable communities of people from India, the Philippines and South Korea, each with different cultures and customs. What do they make of this place, with its temperate climate and lack of density? How have they made their homes here?

I want more narratives that don’t come from Pākehā-centric worldviews. I want to hear about the different experiences of being Asian in Auckland, Invercargill and Hawera. I want to know where the model minority stereotype falls flat, I want to know how East Asian privilege affects brown Asians. And most importantly, I want to read about things that I don’t know the existence of yet.

*

I was born on one island, and I’ve come to live on a different one. 崇明岛 / Chongming Island is a hundredth of the size of the North Island of Aotearoa, and is currently being redeveloped as “Shanghai’s backyard”, a country respite from the fast-paced city.

The first time I went back, I ran up a muddy path to my grandparents’ house. The second time I went back, all the streets were sealed and my grandparents’ house had been demolished to make way for a new hospital. The third and most recent time I went back, I heard that a subway line from the city was in progress.

Once, I asked my grandfather how many generations of our family had been on the island. He said he didn’t know for sure, but thought that it was his grandfather’s grandfather who sailed here from the south, in the 16th or 17th century. I asked if he knew who was on the island before we arrived. He waved his hand.

住岛的人都是移民过来的, came his answer.

All people who live on islands have to migrate.