A Woman, Leaving: An Oral History of 'and what remains'

In 2006, Mīria George’s dystopian play 'and what remains' asked Wellington theatre audiences, “If Māori left the country, would you even care?” The response they got was not what they expected. Adam Goodall collects and shares the story of the play and the rifts in New Zealand that it’s been exposing for a decade.

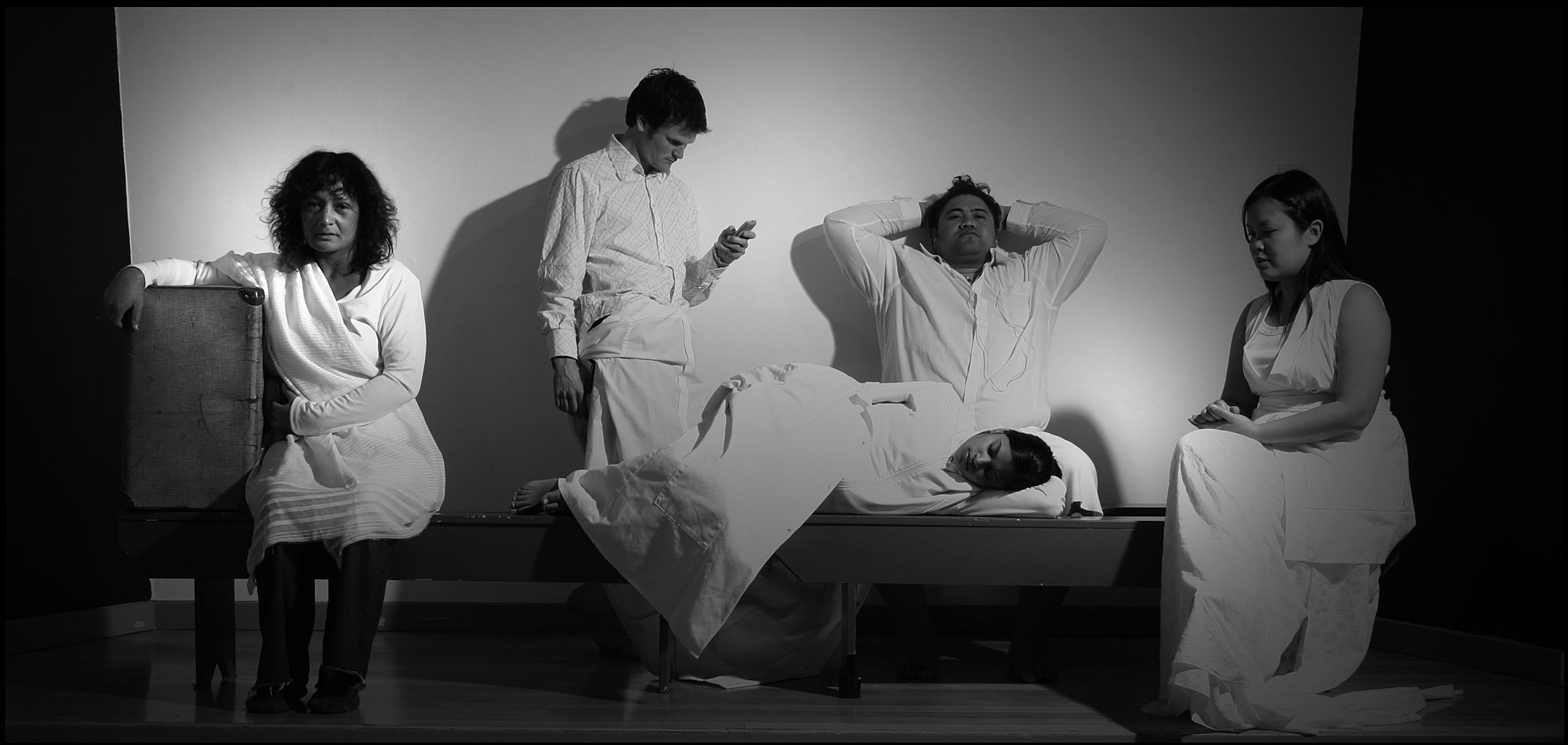

Mary, Solomon, Anna and Ila, all sit silently, politely waiting. They gaze ahead of them, taking in the Departures Lounge, the space about them. However, Ila, at intervals, returns her gaze to Mary. Her stare is not one that is intrusive but one that is genuinely curious.

Ila: You must be leaving.

Mary’s head turns slightly.

Ila: I guess that’s why we’re all here, you know what I mean?

If you were looking for Māori theatre in Wellington at the turn of the millennium, you didn’t need to go much farther than Taki Rua Productions. Established in 1987, Taki Rua had carved out a name for itself throughout the 1990s and early 2000s as the company for indigenous theatre with epic scope and bold design, producing pivotal works like Briar Grace-Smith’s Purapurawhetū and Witi Ihimaera’s Woman Far Walking.

They were so successful and so beloved that in 2006 they took over Downstage Theatre for a victory lap of sorts, mounting a massive revival of Hone Kouka’s play, Ngā Tangata Toa: The Warrior People. An adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s The Vikings at Helgeland, Ngā Tangata Toa transplanted the action to a remote East Coast town in 1919. Taki Rua’s original production in 1994 had secured their place as trailblazers for Māori theatre, picking up several Chapman Tripp Theatre Awards on the way there; this revival, twelve years later, was equally celebrated.

It was also the only Māori play to be produced at a mainstage theatre in 2006 - not just in Wellington, but throughout New Zealand.*

The month before, across the road at the small co-op theatre BATS, a company named Tawata had opened their third production. Tawata was the new kid on the block. Their show was set in the then-future of 2006, in a New Zealand that had wholesale bought into ‘one law for all’. It followed Mary, a young Māori nurse waiting in Wellington Airport’s international departures lounge for her flight out – the last of the tangata whenua to leave.

The show was called and what remains. It had been written by one of Tawata’s founders, Mīria George - a new voice, fierce and visionary, unsparing in her political expression – and had been directed by Tawata’s other founder, Hone Kouka – the old pro, one of Taki Rua’s co-founders way back in 1987, and writer and producer of some of the most celebrated works in Māori theatre’s young history.

Unlike the revival of the epic Kouka had written over a decade prior, and what remains was not universally celebrated.

The response was fierce, polarised, unprecedented. If aroha was in no short supply, there was plenty of whakariri to go around, too. Declared “implausible” by reviewers and “dangerous” by ‘passionate’ audience members, and what remains drove a wedge through its audience. Or, perhaps more accurately, it drew the audience’s attention to a wedge that already existed, and the audience blamed the show for its existence.

Ten years on, Tawata Productions is a giant fish in the small pond that is New Zealand theatre. George and Kouka have produced work by the most interesting Māori, Pasifika, and Asian voices in the country, and fostered those voices through numerous in-house development initiatives. They’ve been nominated for 19 Wellington Theatre Awards in the last five years and won 10, out-tallied only by Circa Theatre and Kouka’s theatrical alma mater, Taki Rua.

They’ve had their hands in a staggering number of significant New Zealand plays: George and Jamie McCaskill’s He Reo Aroha, Kouka’s I, George Nepia, McCaskill’s Manawa, Maraea Rakuraku’s The Prospect, Mitch Tawhi-Thomas’ Hui, Albert Belz’s Yours Truly, Whiti Hereaka’s Fallow, Nancy Brunning’s Hīkoi. Few companies have had a greater impact on New Zealand theatre in the last decade.

Of all those significant works, and what remains is still the one that inspires the most heated debate, though now in classrooms and lecture halls rather than theatre foyers and comments sections. The play is regularly taught as a landmark in New Zealand theatre: a truly multicultural, unapologetically political interrogation of the constant erosion of Māori rights, dignity, and humanity in a Pākehā-dominated New Zealand.

But the play’s continued relevance and influence isn’t purely academic. The mark left by and what remains on Māori theatre – the community, the work, the whakapapa – is still felt to this day, laying the groundwork a new generation of bold, political Indigenous writers and makers. A decade on, we spoke with a number of people who were involved in the original BATS and City Gallery productions about that journey – from its genesis to its fallout.

1. A new kind of energy

HONE KOUKA (Director): Mīria and I are partners. In 2003, I did a workshop production of The Prophet up at Victoria University, and that’s really [when we felt] the first inklings of wanting to get a company together. And then 2004 is where we really kicked in with Tawata.

MĪRIA GEORGE (Playwright): I was nearing the end of my Bachelor’s degree and I had a part-time job working for Te Rūnanga o Ngāti Awa – the Council of one of my iwi, Ngāti Awa. And we were at the final stages of a twenty-five year settlement process. I was really fortunate that our rangatira, Sir Hirini Moko Mead... I was in the same office that he was in for most of my time at Te Rūnanga o Ngāti Awa. So I was really fortunate to be exposed to some of the kōrero and the research that was involved with the whole settlement process for our people.

DAVID O’DONNELL (Head of School of English, Film and Media Studies, Victoria University of Wellington): We had been through an incredible growth in Māori theatre through the 1990s, with these wonderful big epic plays that were often very political.

JOHN SMYTHE (Founder and Managing Editor, theatreview.org.nz): People like Riwia Brown had done plays at the old Taki Rua, when it was in Alpha Street. There was quite a lot happening in Alpha Street at that time.

HONE: Taki Rua was basically the only company that was making a lot of work.

DAVID: In the 2000s, Māori theatre seemed to be waiting for something new to happen. A new kind of energy.

In the 2000s, Māori theatre seemed to be waiting for something new to happen. A new kind of energy.

HONE: Both of us realised there was not a lot of Māori work being made anywhere at that time. So, it was another thing for me to go, “Hmm, okay, where is everyone? What’s going on?”

One thing we both noticed is that a lot of the theatres, the work that was being done was actually really bland [laughs] and there just wasn’t a political focus. It was really, really difficult to find that.

DAVID: [Mīria] was reacting to Don Brash’s speech in Orewa, where he started attacking Māori and saying Māori were “privileged”. He was the leader of the National Party at the time, he could be the next Prime Minister, and he was attacking Māori for being “privileged” and “getting too much money from Treaty settlements” and things like that. What happened was that it sparked this huge Māori backlash in the media and on talkback radio, letters to the editor, where there was an ugly side of Pākehā society coming through and agreeing with Don Brash.

Ila: Why would they want to put a bad spin on that?

Ila becomes a television news presenter.

Ila: And in breaking news tonight, it’s a good one ladies and gents--those May-yor-rees--member them, if you don’t, n’mind, doesn’t matter--cause they’ve left! Finally! All right! Line em up! Who’s gonna be next?

MĪRIA: This is all leading into the Foreshore and Seabed legislation, which was before government at the time. We were building up to the hīkoi as well, the foreshore and seabed hīkoi.

I was in a really intensified environment of politics, of Māori politics, of huge visibility of people taking a stand on the streets, rather than it just being confined to whānau, hapū, rohe, just to tribal regions. It had stepped right into the mainstream and it was a really inspiring and heartbreaking time to be an artist.

HONE: It was really interesting for me, not being part of the Land March in ’75, seeing all of our iwi together. All the different iwi. I marched with Mīria and my girl – who was, I think, seven at the time – and I went, “Go up to your Tūhoe whānau up there. Come back to us at Ngāti Porou. Go to Raukawa. You’re part of all of these iwi.” Just her understanding the political nature of being Māori, you know? And that there were people yelling stuff at us as we were walking along, [and I was] going, “Oh man, y’all guys don’t like us, eh?”

MĪRIA: Something that continued to shine out to me was the length of time our elders and family members had had to commit to advocating and prodding the Crown – our government, bodies of power – into acknowledgment, action, and redress. Our people had spent lifetimes committed to fighting for us.

HONE: The first time I saw [the script], it was called Lost, Again.

2. Lost, Again

MĪRIA: I had written Oho Ake – it was presented in 2004 – and I was told before Oho Ake was even on the stage that I should have another play in my back pocket.

HONE: Miria’s got a really diverse group of friends and she said, “I want to write something for my friends.”

MĪRIA: What I saw on the streets, on the day of the hīkoi, was the diversity of people who came to stand on the street in support of Māori and in support of this call. That stuck with me the most, which is why I really wanted to ensure that and what remains had a multicultural face and that people of otherness were brought into this conversation as well.

The very first idea that I had was actually that image of a woman, leaving. And all I knew about this woman was that she was upset, she was all in white, she had a white suitcase with her, and she had every intention to go.

HONE: You got South Asians, you got Samoan or Pacific Islanders, Māori, Pākehā, you got all mix of people, and really early on, she went, “I want them all in white.”

MĪRIA: I’m from an image-based family; my father’s side of the family are all visual artists. And so a lot of my work is led by image.

So this woman seared her way into my brain and then it just mixed with all of this political climate and I came to understand the whiteness of her dress as being a colonisation, a westernisation, being a dominant force, and that the whiteness of her costume was also shared by everyone else in the cast.

Around 2004, 2005... I think it was around the same time as the death of the Kahui twins**, and some of the letters to the editor, especially, were just horrific. That was a most horrific act that happened to those babies, and then the wider response from the public in regards to the case was chilling. There are some quotes in the play, and what remains, that are taken directly from letters to the editor.

Talks of sterilisation in the media... I don’t listen to talkback radio. I know other fabulous writers find it really provocative. I don’t need more provocation. You would see it bandied about: the sterilisation of Māori. It all bubbled away, and then this play ended up forming.

Ila: You, Solomon, are telling me that when 640,000 people leave the country that you have been born and raised in, it’s not your business?

Beat.

Solomon: Sixteen percent of this country was a problem that we were forced to solve. And we did. That’s what I’m telling you.

Ila shakes her head.

Solomon: I mind my own business.

HONE: When it first came to me, I couldn’t quite grasp it. It seemed like more of a parable, but I went, “Okay, there’s really something in this. There really is.” I remember mentioning it to someone else and their reaction made me go, “There’s really something in this.” They reacted quite strongly – it wasn’t negative, but it was strong – and going, “Right, I haven’t been around this feeling in a long time.”

It got picked up for the [Pasifika Playwrights Development Forum 2005], and that was part of Playmarket. And Mīria had a really bad time with it.

MĪRIA: I ended up having this really contentious and tumultuous workshop process up in Auckland where the dramaturg and the director, we all ended up in a three-way fight. The dramaturg wanted me to stop writing the play and the director didn’t want to deal with it because the dramaturg and I were at loggerheads. And because I was part of a writing group – I was part of this amazing writers’ collective called Writer’s Block that was run by Hone out of Taki Rua Productions, originally, to support new and emerging Māori/Pacific writers of difference – I was used to defending my work, defending ideas, talking about my work and talking about ideas. So I wasn’t fazed having to stand up for my story in a workshop development process with a dramaturg who was also a senior female playwright and who I had asked specifically to be my dramaturg.

The dramaturg wanted me to stop writing the play and the director didn’t want to deal with it because the dramaturg and I were at loggerheads.

She was so offended by the content of the play that when it came to presenting the reading of it, after a week of workshopping, she made me sit on stage with the cast because she thought I needed to take responsibility for what this play was saying. And I was defiant and I was like, “Fine, I’m gonna sit on stage with the cast!” I just sat at the end of the half circle and listened to the play be read.

I just think she didn’t agree with my politics. At first she was suggesting I stop writing this play and write about Māori from a period perspective, which, uh, which wasn’t gonna happen. That wasn’t of interest to me at the time. I would say it was very much her paternal instinct to just shut it down.

That should’ve been a red flag to me. But I was young.

HONE: From that moment onwards, I went, “Yeeeah, this gon’ be good!”

3. Doubling down

HONE: [I came on as director] after the workshop. Because, as I said, it wasn’t a great time for Mīria and I went, “Nah, there’s so much in this.”

MĪRIA: Workshops must have been early 2005. Tawata Productions was doing ‘laboratory productions’ at the time. I think now we either call it a development season or a workshop. We were doing them all at the Tararua Tramping Club, and there were a couple of plays done around the same time: Whiti Hereaka’s Fallow; Albert Belz’s Yours Truly, the Māori Jack the Ripper story; and and what remains.

"It’s 2007, and what remains is set at Wellington’s International Departure’s [sic] Lounge. A young woman is joined by three others, all from differing backgrounds, all there for their own reasons. Departing or among those who will remain. As their stories unfold, as the boarding call nears, a defiant lover arrives, bringing with him astonishing revelations of why her family and her people have departed."

– Excerpt from the Tawata Productions media release for the 2005 City Gallery season of and what remains

HONE: The actors – initially, Mīria wanted all of her friends, but I think three of them got into Toi Whakaari so they couldn’t do it! Yeah [laughs]. So she just looked for others. She went through a big group – Ahi Karunaharan was a good friend of hers, was at university with her as well. Natano Keni was another good friend as well. Sarita So – she wrote that show for them. But none of them have ever done it [laughs].

ERINA DANIELS (Actor, ‘Mary’): I remember meeting all these amazing people, some that I’d known real well, like Rina [Patel]; we were in the same class together.

HONE: They were all from about three or four years at Toi Whakaari.

SAM SELLIMAN (Actor, ‘Anna’): At the end of 2004, after we did our Solo pieces, Hone came up to me and asked if I wanted to do a radio play of my solo. I think that was the first time I met him. After that radio play, we developed a working relationship and I think it was in 2005 that he got in touch with me asking if I was interested in participating in Mīria George’s play. I was very... I was in… not to say ‘shock’; I was very surprised he would ask me because, I mean, it was such a big thing at the time, because it was Hone Kouka asking you if you wanted to do a play.

SEMU FILIPO (Actor, ‘Solomon’): I think the role was meant for one of Mīria’s friends, Asa [Aselemo Tofete], but he was studying at the time. I remember them saying that they were watching TV and a commercial that I was in came on, and they were like, “Oh, we’ll have to get Semu on board.”

SIMON VINCENT (Actor, ‘Peter’): My main work at that time was as an actor-for-hire at Downstage and Circa. I had already struck up a friendship with Hone and Mīria through various meetings and connections and then they approached me with the script.

ERINA: I got a call to come back up to do a workshop of Hinepau with Capital E, and round about that time... I think that was when we had our first workshop of and what remains.

HONE: I’d known Erina from Dunedin. I think I first met her when she was in her early teens, working. We’d known her and she was in a play of mine down there.

ERINA: I was really excited to be a part of the show that wasn’t like a typical… well, I don’t know how you could say ‘typical Māori character’, but it was intelligent and provocative and political.

SAM: When we had our first reading, I had no idea what it was about. I had a hard time grasping that concept of, you know, the last Māori to leave New Zealand because of the political climate.

SEMU: I thought it was a little bit far-fetched but, in saying that, it was great that a writer such as Mīria was really gutsy and ballsy about exploring these issues.

SIMON: I was just amazed by how spare and really well-written the work was. That was what attracted me to it.

ERINA: At that time, I realised that I wanted to articulate all these things that the script brought up for me, but I didn’t have the articulatory tools that I do now to be able to speak to the work and its bigger themes.

HONE: I just jumped at it also because there were all these different voices, talking about us, as Māori. And the character that had the least dialogue was the Māori character. And that’s what I really liked about the idea of it. Because that happens to us all the time. Everyone knows what’s best for us.

Solomon: I think you were the one who was offering to give a shit.

Ila: Then why don’t you give a shit about her?

Ila points at Mary.

Ila: Don’t you give a shit that she’s leaving?

Ila thrusts her arm in Mary’s direction.

Ila: Don’t you give a shit why she’s leaving?

Beat

Mary: Do you mind not pointing?

Ila swings around to Mary.

Mary: Do you mind not pointing?

SIMON: Structurally, it was a three to four week rehearsal process. I mean, any process is defined by the director, the leader, and this was slightly different because it was a new script. But Hone... his approach is extremely disarming [laughs].

SAM: I remember playing lots and lots and lots and lots of games.

SEMU: It was an environment of play, it was an environment of exploring issues, but being safe that whatever you said – it didn’t matter if someone got offended – it was safe, because those are your opinions and they gave you the licence to speak frankly.

SAM: It just loosened us up to battle the take, this topic, head on.

HONE: There was lots and lots of kōrero. Lots and lots of sit down, going, “Well I feel this, I feel that.” It was just great having this microcosm of Aotearoa just debating the shit out this thing, about, “What are we?”

ERINA: I did more and more research, the more that we did the show, about the themes that were really speaking to me, about sterilisation in particular – [that] really struck a chord, with the focus on Mary.

HONE: Working with Simon Vincent – for me, watching him having to deal with all of this stuff, I was going, “You’re awesome, bro! You’re awesome!” Because that was harrowing for him, you know? He was the only Pākehā in the room! And it wasn’t that everyone was going at him. It was him going, “Ho-ly shit! Is this what’s going...?” To his credit, he went, “Wow, this is awesome.”

SIMON: I remember the day that I made the biggest realisation and what led to my ‘epiphany’ around the work, when we were all talking about our families. There’s a quote from Semu’s character: he says “third generation”, talking about his place, how long his family’s been in Aotearoa. And we ended up talking and I said, “I’m first generation New Zealander. My parents came over here in the ’70s. I was born here, but they weren’t.” And it really challenged me, because I was the newest immigrant to New Zealand of the people in the room. It challenged the sense of privilege, I guess, I didn’t even know that I had. It really made me think about things very differently, and think about the things that you take for granted as a Pākehā in this country.

ERINA: Coming into the news more and more were the stories of our babies in Aotearoa being killed, and such a spotlight was put on brown babies being killed by brown parents or brown others. I was really sensitive to the talk at the time - on Newstalk ZB or in the papers or coming from politicians - about “what’s got to be done about this”.

MĪRIA: The name Lost, Again was replaced by [the] sharpened title – I guess, I would call it “sharpened” – and what remains. Because, by the time we were approaching that City Gallery season, I was clear the question I wanted to ask New Zealand was, “If Māori left our country, would you even care?” Because I didn’t think, at the time, that anyone would care.

4. Saving hard

Solomon: Who needs an Overseas Experience? Who needs a rite of passage when every single day already feels like one?

Anna: Those who can afford it?

MĪRIA: I remember we couldn’t get funding for the production.

"Despite international workshopping, an international festival invitation and Mīria being awarded Emerging Pacific Island Artist of the Year [2005], and what remains failed to receive support from creative funding bodies. and what remains will be entirely self-funded."

– Excerpt from the Tawata Productions media release for the 2005 City Gallery season of and what remains

HONE: Basically, my scriptwriting paid for it. And Miria was working full-time as well. [And I was] working at the [New Zealand Film] Commission as well.

“We had an award-winning director and designer and didn’t get any funding so my mum and I put money in to fund it – there was no other way to do it,” [George] says.

– “Universes in the Head”, Mana Magazine, June/July 2006, p. 76

HONE: We put applications in and the script went in and a couple of signals coming back were, “We don’t like this.”

"Tawata Productions made an application for funding for a project entitled “Lost Again” in the first funding round of 2005/2006. The application has been declined….

The application file, including assessors’ comments, was destroyed in accordance with Creative New Zealand’s document retention policy. This policy is approved by Archives New Zealand and is in line with our statutory obligations."

- Excerpt from Creative New Zealand response to “Official information request for information relating to Tawata Productions (ref. 152)”, dated 16 June 2016

MĪRIA: I won an award [Emerging Pacific Artist - Arts Pasifika Awards, 2005]. I went and picked up the cheque at the award ceremony, and it went straight into the production.

5. Within the gallery walls

HONE: We came back from Auckland and we said, “We don’t want to do it in a theatre,” so got in touch with City Gallery.

MĪRIA: Theatre in New Zealand at the time for me felt so colourless and of no great import to me as a person or to the people I knew. To be in the City Gallery, where contentious work happened, provocative work... to have an uncomfortable conversation or go on an uneasy journey, with the gallery walls... [it] seemed to be the most appropriate place for us to be.

HONE: Just looking at the works of Shane Cotton, Peter Robinson, Jacqui Fahey... y’know, there are all these visual artists – John Walsh is another one – who, in regards to us as Māori, have depth. There was a resonance there and there was a need to engage.

MĪRIA: We were so lucky that Tracey Monastra was there; she’s also a fabulous theatre designer, which is probably why she championed Tawata going in there. So we had this premiere season of and what remains that was staged in one of the main gallery spaces downstairs, amidst a Jeffrey Harris exhibition.

SEMU: The space was an interesting space to work with, and I think the soundscape we had, and the minimal lighting, really, really worked.

STEPHEN GALLAGHER (Sound Designer): I worked on a show called Te Karakia with Hone. Hone directed it and I was designing the soundscape. And that was the first time I’d ever worked with him, and that’s how I met Mīria.

I wanted to make it sound kind of heavy and oppressive. So there was a lot of low-end frequency that felt… ‘sweltering’, was the word I remember thinking about. And then I was thinking, “I wonder if I can make a soundtrack that’s basically just filtered white noise, or close to that.” So it’s like this nullification, really, of everything that [Mary] held dear as a person and a culture.

Mary: Dad left about a month ago.

Anna nods.

Anna: Did he take with him many things?

Mary smiles.

Mary: No, he didn’t take many things. It would’ve taken him a long time to pack up everything - he’s been in his place for ages, since I was little, since before I was little! Dad always kept pieces of every moment in his life - photos, invitations, matchbox cars and porcelain pukeko, newspaper clippings - there was a lot of stuff!

Beat

Mary: But he didn’t take with him many things. Only the essentials.

Anna: What are the essentials?

Mary laughs.

Mary: He asked me that too.

SEMU: What I liked about the City Gallery was that, because it was so small and intimate, it actually amplified the setting and our performances.

MĪRIA: After opening night, Hone got a call from Carla van Zon [then-Artistic Director of the New Zealand International Arts Festival]. She had come on opening night. I could hear her responding to the production. She must have seen the review already, because I certainly hadn’t seen it. I think she said something to Hone like, “It doesn’t matter, it was important, and it was a great show.”

I think we had more Gallery-going audiences and probably more Tawata-going audiences coming to that season, because, apart from the reviewers, I had a really positive response from audiences.

But that’s probably the first sort of signal that we had, or I had, that there had been a strong response to it.

6. Shifting

"When and what remains was first staged, in 2005, many people said it was fanciful and that would never happen here in New Zealand. Unfortunately, less than one year later, these fanciful ideas are becoming a reality."

– Excerpt from Hone Kouka’s Director’s Note in the programme for the 2006 season of and what remains at BATS

MĪRIA: There was enough interest for us to bring the show back and there was international interest stirring as well. So we were determined to return the show to Wellington and for me to sharpen as a writer as well. With Tawata, we do more than one season with our works because it allows all of the creatives involved in making the work to understand it better with each time.

HONE: It changed with BATS because it was going into a theatre, so we had more control theatrically and with the image system that we’d created. And we had a set! You know, I think in City Gallery we had about five lights, so obviously going to a full rig, you know? [Laughs.] That changed it dramatically.

STEPHEN: The City Gallery’s air conditioning... I’m not sure if you’ve stood in that space, [but] the air conditioning going over the sound, that was pretty heavy [laughs]. A lot of the details in the soundtrack got covered or masked in the gallery version.

HONE: Tony DeGoldi’s design – he had a sort of runway for it. Runway, as in fashion runway. And again, he just used big blocks of white as well. And Robbie Larsen did the lighting for it as well, for one of the seasons. [Robbie was the lighting designer for the BATS season; Jennifer Lal was the lighting designer for the City Gallery season.]

MĪRIA: There were no major changes in regards to story or character. It was just sharpening and refining the way we told our story. That would have been the main point of focus from after that first season, because as a writer, when you’ve experienced it with an audience and when you’ve received a feedback from an audience, you know what’s sticking and what’s not. And I think that’s when I first realised that, even though Solomon had the same politics as Peter, people only really heard Peter’s politics; they didn’t hear Solomon’s.

Peter: We’re talking about the Steamers, not the All Blacks…

Ila: Not very black now, are they! That’s real politics for you! By god, it’s the World Cup next year – Jesus, we’re screwed! I’d like to thank the Liberal government for destroying every last chance of winning back the World Cup!

Peter smiles sternly.

Peter: First generation Liberal supporter. My children will be the second.

Ila: Oh, it is a threat!

Solomon: Second generation Liberal supporter myself!

Peter: First generation…

STEPHEN: I thought the show had really tightened up. I thought it was a much more elegant version of the show.

HONE: The major difference was you had a visual arts crowd and a theatre crowd. And the theatre crowd, at that time, were way more conservative.

7. Fallout

MĪRIA: The response from theatre-going audiences was… was… really… tense.

HONE: There was a need for people to engage. Even if it was in a negative [way], there was an absolute need for them to engage. And the negative... it was really interesting.

STEPHEN: A lot of people just, at first, brushed it off as kind of a farce and unbelievable and impossible to take seriously.

MĪRIA: Other theatre practitioners – and again, mainly women – told me that it was dangerous what I was doing and that I was a separatist and that it wasn’t right.

Other theatre practitioners – and again, mainly women – told me that it was dangerous what I was doing and that I was a separatist and that it wasn’t right.

ERINA: One of my mates, who I really enjoy – she’s a real big thinker and is passionate about theatre – I remember her coming to the show and I remember her displeasure at the themes of the show. How passionate she was about how inconceivable it could be, how angry she was that such a premise would even be posited. In relation to my mate’s reaction, because I’ve got that relationship with her, I can sit down and have a talk-story with her and we’ll have a debate about whatever points that she thought about and then I could have a kōrero with her about it. But I know that she went and had a talk with Mīria.

MĪRIA: Another woman, another theatre practitioner, said to me, “I go to the theatre to be entertained. I don’t go to the theatre to think.”

HONE: I don’t think Mīria was ever devastated by the reviews but they were pretty bad! [Laughs.]

DAVID: I was absolutely astounded at the critical response from the two main Wellington critics, who gave it really bad reviews and said that the whole thing was ‘inconceivable’ and they didn’t seem to see any merit in it whatsoever. And I thought, “Am I going crazy? Because I actually think this is one of the most exciting New Zealand plays I’ve seen for a few years.”

JOHN: I could see it was addressing a really important thing, because the whole business of the Don Brash Orewa speech was very current. And, you know, everyone was appalled and a great deal of debate had raged around it.

MĪRIA: I remember John [Smythe] said, “Inconceivable.” Which was… yeah. That’s what he thought. Cool.

"Sadly I have to conclude that And What Remains does not, and cannot, work either politically or theatrically because it takes an absurd premise to an absurd conclusion. We can appreciate skilled performances, stylish production values and moments of clear recognition - of ourselves, each other and the political landscape we live in - but in the end the 80-odd minutes of strutting and fretting upon this particular stage signifies little of value."

– John Smythe, “Inconceivable”, theatreview.org.nz, 29 August 2006

"The play is, as Hone Kouka writes in the programme, unashamedly about politics and it is a warning that our civil liberties are being eroded, that new injustices are occurring. But to leap from the foreshore and seabed controversy and other contemporary problems to mass deportations, ethnic cleansing, The Liberal Government of 2010 (it was 2008 in the first production) forcibly sterilising all Māori women, and that Mary is the last Māori to leave Aotearoa is to stretch credibility to the breaking point."

– Laurie Atkinson, “Implausible Leap of Faith Required”, Dominion Post, 30 August 2006

JOHN: I just didn’t think the set-up of the play served the debate terribly well, because there were so many things that were already a fait accompli, and I had to go, “Wait, hang on a minute, how could this possibly happen? Where, in which country, which version of New Zealand is this that I don’t know about where everyone could roll over and let it happen – including Māori?” That was almost the biggest thing. The idea that there had been no revolution around it just gobsmacked me really.

"I would hardly call this meek. Her character Mary, to me, embodies the frustration of a struggle of a people. How long must they fight? How long will it take to be heard? How many generations will this take? Is 160+ years not enough? When, after all this, do you finally resign? When do you decide that you've had enough, you're too tired to keep on fighting, that it is time to go?"

– Sonal Patel, comment (posted 29 August 2006) on John Smythe, “Inconceivable”, theatreview.org.nz

HONE: Some people couldn’t ask that question, coz they went, “Well it’s ridiculous that you’d think Māori would leave.” And [we were] going, “Look, just ask the question!” Look at Ionesco and all of this other theatre that’s looking at these things. Yet for Māori, we cannot ask a question like, “What would this country be without us?”

JOHN: As I said in the review, all the discussion after the play seemed to be, “How could this happen?” You know? Which I thought was a couple of steps behind where the debate needed to be. We needed to believe in the possibility of it in order to be able to address the issues that it wanted to be about.

HONE: To be really honest? Primarily, it was coming from Pākehā.

"There are today in New Zealand some VERY important topics we should be discussing; sadly, this is yet another example of a very silly play that completely fails to engage with any of them, and so any chatter generated is utterly pointless. All heat and no light, as usual."

– ‘Angst Hadenuff’, comment (posted 30 August 2006) on John Smythe, “Inconceivable”, theatreview.org.nz

JOHN: It was probably your standard Pākehā theatre audience, Wellington theatre audience.

HONE: Some of the most intense response came from older Pākehā. And they went, “But we helped you.” And we were going, “It’s not about you. It’s about us.”

MĪRIA: It was just… I mean, it’s wonderful that they came to the show, but unfortunately the show didn’t inspire a dialogue and instead it provoked a really angry response.

ERINA: None of the brown people that I was around thought that it was inconceivable. We all can see how it has happened in the world’s history and we all can see how it could happen.

JOHN: I think it wasn’t until the discussion opened up on Theatreview that the Māori voice came through. And the final comment, in te reo, was a conciliatory one. It acknowledged the validity of Miria’s point of view and my point of view and it was like someone doing a classic marae conciliation at the end, so that everybody felt acknowledged and recognised and valued, and I appreciated that.

"Nga mihi nui ki a koe e Miria mo tenei whakaari hohonu mo ngai tatou te iwi Maori. Ki ahau, he whakaari pouri hoki no te mea, i kite au i nga rangirua katoa e ai ki ngai tatou. Ko te tumanako me whai whakaaro, whakawhiti korero hoki tatou nga tangata katoa o te motu nei ahakoa ko wai, ki nga take o tenei whakaari. Kia koe John, tautoko au ki ou whakaaro, kahore au i te whakapono i te mea ka wehe ngai tatou ki Aotearoa nei, engari me whakaaaro tatou ki tenei whakatuaki [sic]... Ma te wahine, me te whenua, ka ngaro ai te tangata. Tauke Miria!!

[I would like to acknowledge and give my gratitude to you Miria for your show, which has a lot of depth and meaning for the Māori people. Personally, I also found this to be a sad play as it showed the uncertainty we Māori face in this world. It is my hope that no matter who we are in this country, we can be considerate, and we can discuss and deliberate the issues that are presented in this performance. To you John, I support/agree with your ideas/opinions, because I do not believe we in Aotearoa are divided, but we should consider the following proverb… “By women and land do men perish.” Way to go Miria!!]"

– ‘Mahinarangi’, comment (posted 1 September 2006) on John Smythe, “Inconceivable”, theatreview.org.nz

HONE: I’m lucky enough to walk in both worlds easily, but very few Pākehā I know can come into the Māori world and do the same sort of thing. But we’re expected to do that all the time. So, that’s the thing, going, “I’m going to stand here and you come over here.” And that was what I realised was the hardest thing in regards to this kōrero. “I don’t want to, it’s not my world.” But you’re going, “But this is this person’s world.” Why don’t you want to hear what they’ve got to say? That’s the basis of theatre.

SIMON: People felt that the actual text was ‘to blame’. That was challenging for me, because as I’ve made clear I believe it’s a very strong piece of writing and so that was… I didn’t agree with that.

HONE: No one talked to me. Which is really interesting. Perhaps I have a reputation that I’ll just come at them!

SIMON: I was present when other people had things to say about it. I wasn’t directly challenged, no.

ERINA: My kōrero with people afterwards was generally positive.

MĪRIA: If I was at the theatre when the show was on, I wouldn’t come out afterwards. I stopped. I was avoiding the audience.

"Imagine: (at least) two simultaneous and distinct discussions about the play, each drawing on different kaupapa, different access to information and different contextual understandings. Funny thing is, that’s exactly what makes the play seem so believable."

– Alice Te Punga Somerville, comment (posted 29 August 2006) on John Smythe, “Inconceivable”, theatreview.org.nz

MĪRIA: It felt like it went on for ages, because I remember there were, like, theatre tutors, and there were people involved in the industry who’d taken offence to the production, and so then I would hear about it. I heard about it for ages, for absolutely ages afterwards.

HONE: People had no problem coming at Mīria in regards to what their issues were with this thing.

MĪRIA: It was a really tough time. After that BATS Theatre season, I did find it challenging to stay positive about our art form and the New Zealand theatre industry.

ERINA: It just wasn’t the best forum. Or was it the best forum? When is ‘the best forum’ to have a talk about this?

MĪRIA: [But] I remember other young Māori theatre practitioners who were around at the time were… I remember them saying, “Oh, I didn’t know that this was happening,” in regards to the politics of the Foreshore and Seabed legislation at the time. I remember them coming up to me afterwards and asking me, “Why would you use sterilisation as an example?”

Māori theatre has a history of protest; Māori theatre was born out of protest! In the late ’70s, in the ’80s. So, the conversations that I remember senior Māori theatre practitioners having with me at the time – there were actors and writers – I felt huge tautoko, or huge support, there.

"I want to say thank you for your support and awhi towards our roopu – we felt very much looked after and appreciate that. I hope it was a positive experience for Bats – at the very least it got a LOT of people talking about a piece of theatre and that can only be a good thing."

– Excerpt from an email from Hone Kouka to BATS Programme Manager James Hadley, 6 September 2006

8. Recovering the kōrero

Anna: Why do you want to go?

Mary stops.

Mary: Because I’m tired. I feel so tired.

Beat.

Anna: Why are you tired?

Mary: Because here…

Mary motions to the floor.

Mary: … I keep losing. I lose things that others have, that I should have. But I don’t have because I am… because I am. I am one person and I am everyone. When I fall, or when I make one mistake, my family and I will be judged by one mistake. We are all judged by the mistake of one person.

Mary laughs to herself.

Mary: How many times do we gather peoples together and hikoi the length of this country in protest?

HONE: From that presentation [at the Pasifika Playwrights Development Forum], she got an invitation to Pasifika Styles in the UK.

"… the Pasifika Styles Festival took place over a week in May 2007, one year later than originally envisaged, a delay caused by the exigencies of funding. Three plays by Maori and Pacific Island playwrights were shown for the first time in the UK in Cambridge venues, and short film screenings were held at the Museum, together with an Activities Day led by Pacific artists. Produced by Alexander Leiffheidt of Far Cry Theatre in association with the Museum, the Festival once again brought the living faces of contemporary Pacific art to Cambridge."

– Rosanna Raymond and Amiria Salmond, Pasifika Styles: Artists Inside the Museum (Cambridge/Dunedin: University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology/Otago University Press, 2008), p. 20

ALEXANDER LEIFFHEIDT (Festival Director, Pasifika Styles Festival): The rationale from the start was to present contemporary Polynesian culture that would very clearly, for a British audience, be dealing with relevant, current questions – political questions. We were quite clear from the start, we didn’t want anything that would vaguely resemble Māori or Polynesian folklore – you know, anything like that. We wanted to present it as very now, very current. And obviously Mīria’s play fulfils that in more than one way.

ROSANNA RAYMOND (Co-curator, Pasifika Styles): I was just, like, thrilled with it! Because it was so left-field. The whole concept of the last Māori remaining in New Zealand – and was leaving! – I mean, it was just incredible.

ALEXANDER: And also as an idea it’s quite radical. So that was one thing that was appealing. The other thing is also, in terms of aesthetics, in terms of what vision of theatre is behind the production, I thought Hone’s take on it was very interesting.

ROSANNA: and what remains was actually a very contentious issue – not for us; we loved it – for the likes of Creative New Zealand. They were very discouraging, because they were – they used this word a lot – “concerned” about how the English audience would view race relations.

ALEXANDER: It is possible that when we said, “Okay, we want to programme and what remains,” they weren’t overly happy about it. That is a possibility. But, as I said, I only remember this vaguely, and the fact that I remember it vaguely probably means that it wasn’t too clearly a big deal. It might be that Rosanna, who was in New Zealand more often than I was, noticed more than I did.

MĪRIA: It felt like it wasn’t until I got to the UK with the show that I was reminded why the show was important, that this kōrero was vital and should be told.***

HONE: When we did the show in London, two young Irish women came up and went, “Yeah, we’ve had this, I understand this.” And then there was a young Turkish guy talking the same sort of thing.

ROSANNA: I just remember afterwards, the buzz. There was a real buzz. There was a real, sort of, people were talking because, you know, what if that situation ever happened? People were really like, “Wow!” And it wasn’t what they expected of Māori theatre, too.

MĪRIA: and what remains was such an unusual creative experience because the most comfortable I felt with that show was in its fledgling stages at the City Gallery, and then when we took it overseas, where it was really warmly received and wanted, and there was so much wonderful conversation after the production.

SAM: This is one of the plays that I really keep close to my heart, because it’s taken me places. It’s taken me to the UK, to tours. In that way, I have a lot of aroha for that piece.

DAVID: I mean, it was the sort of play where you felt like somebody should pick it up. Like a larger theatre should program it.

HONE: It keeps popping up, all over the place. Our Canadian friends, they’re very keen to have readings or productions of it themselves because, for First Nation Canadians, there was a law in regards to sterilisation of their wāhine.

DAVID: I got in a debate with a student once because I compared Mīria’s use of repetition in the play with Shakespeare’s use of repetition in King Lear, where he repeats “nothing” several times. “Nothing, nothing will come of nothing...” One of the most famous bits of Shakespeare is this very simple repetition, and Mīria has similar repetitions of simple words like that in this play, which I find very theatrically powerful. And so a student put their hand up in the class and got really angry and said, “You can’t compare Mīria George to Shakespeare!” And this created a big debate because some people said, some Māori students said, “I’m actually more interested in this play than I am in Shakespeare.”

JOHN: I’ve got a lot of admiration for her as a writer and a lot of admiration and gratitude for Tawata being there to let her… And, you know, I’m quite happy to accept that I’m a minority opinion in this.

SEMU: Even just thinking about it and to write a play, I thought, “Man, she’s got tremendous guts.”

SIMON: Had I not done this show, I wouldn’t necessarily have come up against some of the very challenging questions that I had to face. I don’t know if that would have happened, and so I’m enormously grateful that I was able to participate in the work.

ERINA: I’ve been focussing on making, and a lot of my other mates have been focussing on making their own work, and there’s been a lot of light and laughter and comedy in the work that has been made recently. When I think about and what remains, it’s a different energy that runs through it. There can be lightness and joy and comedy in it, and there is, but also at the base of it, for me, there’s a real deep river flow, a push, an urgency, and a weighted meaning, fullness, that [the play] represents in the whakapapa of the works that I’ve done. I feel really lucky to have been given a chance to be a part of that.

MĪRIA: It taught me to be strong as an artist, and to fight tooth and nail for what you have to say. Because after the BATS Theatre season, it felt like we had to fight for the right to have a perspective on what was happening in our country, right then and there.

I think we need protest more than we ever did before. In regards to ourselves as Māori, in regards to sovereignty, in regards to protecting the environment, in regards to protecting and caring for humanity. Protest, for me, is how we can care for ourselves and each other and the ecology around us. And so that’s what theatre is to me. It’s my form of protest. I’m inherently an artist but my art form is theatre and I know through my art form I can protest.

HONE: and what remains really was the great catalyst. It got us moving.

MĪRIA: My mum keeps telling me that I have to write another one.

*Hone Kouka 'Re-Colonising the Natives: The State of Contemporary Māori Theatre' in Marc Maufort and David O’Donnell (eds.) Performing Aotearoa: New Zealand Theatre and Drama in an Age of Transition (2007, Peter Lang) p 238.

**Note: Cris and Cru Kahui died of head injuries in June 2006, during the rehearsal and revision period for the BATS season of and what remains. During the late 1990s and 2000s, there had been a number of prominent child deaths resulting from abuse that had triggered the same wider response from the public, most notably the deaths of Hinewaoriki ‘Lilybing’ Karaitiana-Matiaha, James Whakaruru, Tangaroa Matiu and Anahera Ross-Lewis.

***Simon Vincent and Rina Patel were unable to tour for the Cambridge and London seasons. Instead, the roles of Peter and Rina were performed by Matt Saville and Rashmi Pilapitiya. Semu Filipo was later unavailable for the October 2007 Radio New Zealand recording of the play and Aselemo Tofete performed the role of Solomon.