A Lunar Cycle of Fasting

Despite our differences, the moon connects us all. Lana Lopesi reflects on this year’s Ramadan, and her relationship to food, allyship, other people and the lunar cycle.

When the new moon was sighted on the night of 23 May, somewhere between one and two billion people the world over came out of a month-long fast. This annual fast means, for many, no food or drink, including water, is consumed from sunrise until sunset. The roughly 30-day fast is also a time for charity, celebration, prayer and (in usual circumstances) of coming together. For Muslims, this new moon on 23 May marked the end of the month of Ramadan, and the start of a new month.

This year, I joined those billions of people and fasted for Ramadan to support my partner. With the closure of masjids, people couldn’t pray or begin and end daily fasts together, so Ramadan was experienced largely through distance. With the absence of community elsewhere, it felt important to have the communal aspect of Ramadan in our home, even if it was just the two of us at suhoor and iftar each day.

As the photos of panic buying seemed endless, supermarket shelves couldn’t be refilled fast enough to satisfy our voracious appetites, and people found lockdown joy through baking bread, fasting became my circuit breaker. It offered moments to reflect, and gave me something other than media briefings and Twitter timelines to care about each day. Revisiting those moments, this piece is a collection of my reflections on food, others, moon cycles and allyship.

Food

Ramadan is a holy month that marks Allah revealing the first chapters of the Quran to the Prophet Muhammad. From what I’ve been told, it’s a social time of prayer, scripture and of course fasting. Yet it’s usually the fasting element that seems to dominate mainstream understandings of what Ramadan is. Though we may not realise it, fasting is all around us. It doesn’t take much effort to find examples of established, and at times ancient, fasting practices.

All I saw was excess. All I saw was our pantry privilege.

Perhaps the most well-known example of fasting in this part of the world is Lent, which is observed by Christians, specifically Catholics, who give up certain foods or behaviours for 40 days and 40 nights. Yom Kippur (or the Day of Atonement) and Tisha B'Av are days of 24-hour fasts observed in Judaism. Fasting in various forms is commonplace in Buddhism and Jainism. Bigu is a process of cleansing and spiritual refocusing found in Taoism. And Purnima, or the full moon, is just one of many times a Hindu might fast. In addition, Indigenous people the world over practise periods of fasting in various forms and for various reasons.

The Sāmoan word for fasting is anapogi, and in pre-Christian times it was part of a process that induced a dream-like state called moe manatunatu, which enabled a person to converse with ancestors. Today, fasting is still very much alive and well across the archipelago, although it’s mostly subsumed within Christianity. While people on social media scoffed when Sāmoa declared a week of fasting and prayer as part of its State of Emergency Orders issued as a result of Covid-19, it seemed to me like an appropriately Sāmoan thing to do.

Today, in the environment of body sovereignty and hyper-surveilled bodies, fasting as discussed in the mainstream has more to do with diet culture. Intermittent fasting, cleansing and detoxifying can at times be proxies for eating disorders, food trauma and body-dysmorphic habits. When I declined food or drinks from family or friends and then revealed I was fasting, I felt like I was saying a dirty word. I was met overwhelmingly by a sense of shock that people could (and would want to) abstain from food and drink (as well as other things, like sex) for periods of time, while others offered unsolicited ‘medical’ advice and concerns for my health. While Ramadan is about so much more than fasting, I think one of the deepest reflections I have is on my relationship and connection to food. I think I should just say upfront, that over the month observing Ramadan I gained seven kilos (and my partner even more), so fasting does not necessarily result in weight loss.

I felt an impulse to give.

During lockdown, a time when food brought me more joy than ever before, I spent the first week eating myself out of home. At the beginning of Ramadan, as I adjusted to this new abstinence from eating or drinking, I spent most of my afternoons in the kitchen cooking various elaborate meals that were too big for my family of four, and baking desserts to follow that up. This over-cooking was partly a way to distract myself from hunger, as well as creating rewards for ourselves for lasting the whole day. And honestly we just didn’t have enough hours in the night to eat it all.

It’s a funny thing – as that hunger creeps in throughout the day, you start to imagine just how much you will eat and all the different things you want to taste. Your desire for food intensifies. I would pass time drooling over food porn on Pinterest and then making all the things. It was on the third day of Ramadan, when I looked at my partner over mountains of dinner, that I felt that insatiable desire fall into an empty void in my gut, never to be satisfied. What was previously a relationship with food that was based on a general guilty feeling (the kind we’re conditioned to feel for eating at all) was now a no-holds-barred approach to food: as soon as the sun had set I could eat anything and everything I wanted, but it never felt quite as good as I thought it would. Instead, for the first three nights I lay in bed cradling my stomach in the foetal position only to fill it up again at 4am Suhoor, our last chance to eat or drink until the sun set again.

All I saw was excess. All I saw was our pantry privilege.

From then on the excessive cooking ceased. I noticed that my feelings of guilt lifted and my unconscious behaviours weren’t stopping me from eating across the full food spectrum any more, and with that the desire to overindulge disappeared. Instead I made sure we had just enough. I felt like I woke up to the fact that food (which for so long was my medicine) was not going to run away. And insteadthat desire to cook and bake for myself and my family was refocused on cooking and baking for others, and – once we could – who that food could be shared with.

Others

I had heard people say that to feel hunger during Ramadan was about developing an empathy for others. I was kind of cynical about it to be honest. But I do think that if I hadn’t entered this moment of fasting, I’m not sure that I would have been able to pull myself out of this isolation slump. It gave me clarity in a way that helped me to see beyond myself, to appreciate what I have and to ask what I could give to others.

The moon is the ultimate timekeeper. A mutual symbol of what we all share.

Charity is one of the five pillars of Islam, which means that for those who can afford to, zakat should be considered a mandatory and systematic annual gifting of 2.5% of one’s accumulated wealth to benefit the poor.

I don’t know how to explain it, but as the fast went on and the days became easier, I felt an impulse to give. Admittedly it was little bits here and there, giving what I could, buying artworks, books or whatever was for sale to support the creative economy. Closer to home, it was making food to drop off to our families. Or giving time to those who needed it. But more than the actual act of gifting, it stirred an awareness about keeping others on my mind.

Moon cycle

One thing that I have found comfort in in the past couple of years is astrology. Something bigger than me to explain my toxic behaviours to myself or to explain why at certain times it feels like me and the world around me are feeling some kinda way.

Astrology has had a really interesting rebirth in the last few years and, while some people are sceptical, moon cycles play such an intense role in almost all expressions of spirituality. It’s hard not to see it all as being related, with the moon offering some type of larger-than-thou way to connect us all.

The place of lunar cycles in te ao Māori has gained prominence in public discourse in recent times with a growing recognition of the significance of Matariki; it is even being considered as a possible public holiday this year. Matariki is the name for a cluster of stars, and the period of time we call Matariki is when that cluster is visible (starting three or four days before a new moon) around June and July. It’s a time of celebrating new and old life, planning for the future and gathering with loved ones.

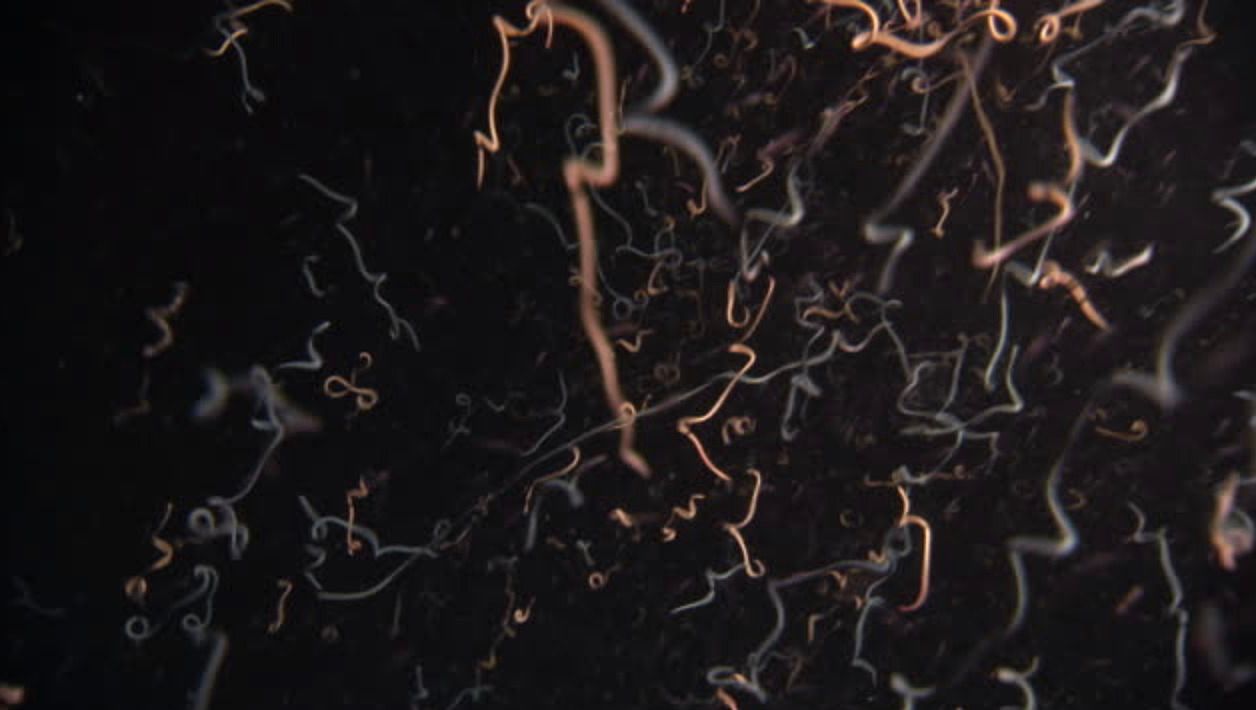

Still of Palolo rising to the surface making its annual appearance in Tutuila (American Samoa). Getty Images.

In Sāmoan, this same constellation is called Mataalii (eyes of the chiefs), and the moon cycles too played a key role in the civic life of Sāmoa before the introduction of the Gregorian calendar. In some places, each of the 12 lunar months was known by the name of a god, or atua, who was worshipped for the month. But it was the onset of spring that was said to be the start of the year, a period of time known best for the fishing of palolo. Palolo is a species of sea annelid that lives in the coral depths. Once a year it releases a portion of itself – a worm-like sac of eggs and sperm. The head stays in the depths and regenerates itself until the next year.

My partner and I ran outside at 4am on 23 April, thinking the new moon would be visible, signalling the start of Ramadan. We saw nothing, which is exactly what you’re meant to see at a new moon (it’s when the side of the moon you see is not lit by the sun at all) – we looked up at the sky, looked back at each other and cracked up laughing. All this talk about moons and we had no idea how to read it or what to even look for.

As an islander who is disconnected from the lunar cycles that once governed life, astrology feels like a way to develop my lunar literacy. My partner laughs when I rattle off personality traits of various star signs, but there we were a whole lunar cycle later. Having learnt our lesson from our first new-moon sighting attempt, we were waiting for May’s new moon to let us know we could eat and drink water during the day again, signalling the end of Ramadan.

The moon is the ultimate timekeeper. A mutual symbol of what we all share.

Allyship

I’ve been thinking a lot about allyship.

Over the month, people’s reactions to my fasting were varied, but more than anything they wanted to ask if I was Muslim. I saw faces change, body language shift and eyes open wide. I saw how little connection the people around me had with Islam, to the point of visible discomfort. And when I told people I’m not Muslim, but fasting in solidarity with my partner, I saw the relief in their faces. Only last night, a week on from Eid-al-Fitr, I noticed people who had followed me on Instagram now suddenly unfollow me, from what I can only assume is because of my (very minor) Ramadan-related Insta stories. And if I’m noticing Islamophobia around me as someone who doesn’t ‘present’ as Muslim, and after only one month of fasting, I can’t imagine what it really means to bear the brunt of Islamophobia.

How does allyship as a nation actually work long term?

Two years in a row our Muslim community in Aotearoa has been rocked to the core, first with the terror attacks and now with Ramadan in isolation. I’ve been thinking a lot about the way my Facebook timeline over a year ago was flooded with messages, articles, illustrations and photos of support for the Muslim community, and yet those same people have no cognisance of Ramadan happening. What does it mean to rally around people when it shakes our own national understanding of ourselves, but to not actually engage with that same community or their beliefs again? How does allyship as a nation actually work long term? Somedays when the fast was hard, I thought about what it meant as a non-Muslim to fast with my partner. Especially if the fasting is not accompanied by prayer and building a spiritual connection with Allah. I have no idea how to answer these questions, and I’m not sure that I ever could. But I think they’re good questions for all of us to sit on.

I have used my time this month to school myself on Islam, reading work by Muslim women authors and following Ramadan vlogs. And I think allyship, to me, has been actually sticking by the sentiment that was expressed last year, when we all of a sudden noticed our ‘Muslim brothers and sisters’ before they became invisible again. It’s been about learning and confronting the attitudes that make people shift in their seats.

*

Observing a practice which is not mine has taught me that being an ally is more than just paying lip service. It’s about developing genuine empathy for and understanding of others by sharing the ways we are in the world. My biggest reflection is that with all our energy focused inwards as we are isolated and distanced from each other, we still need to connect outwards. In a time when the one thing that has brought everyone together across the globe is a pandemic, maybe we should spend time learning about the lunar cycles that we all share instead? And perhaps learning more about these cycles, and what they mean to others, can be a new gesture of care. A gesture needed more now than ever.